The best single-seat fighters of 1945: European Theatre World War II

Technology was advancing rapidly towards the end of the war with the most powerful piston-engined types the world had ever seen fighting alongside or against the first jet aircraft. But how did they compare?

(The following is from Spitfires over Berlin by Dan Sharp)

There were around 20 high performance fighter types at least nominally in service in Europe* when the war there came to an end. Each had its strengths and weaknesses – a higher top speed, a better rate of climb or simply being quicker in a turn, but it is worth bearing in mind that even the best aircraft in the hands of a novice was usually a poor match for a lesser machine in the hands of an experienced ace.

The ‘official’ statistics available for each machine have been endlessly scrutinised in the decades since the war’s end and some of the figures, for example for top speed, were achieved only under special conditions – with particular equipment fitted and at a particular altitude. The fastest Messerschmitt Bf 109, the K-4, for example, has an ‘official’ top speed of 440mph, but this could only be managed with methanol-water injection (MW-50) to allow increased boost pressure in its DB 605 DB or DC engine, and then only for a maximum of 10 minutes. It also required a broad-bladed 3m diameter VDM 9-12159A propeller and even then the 440mph was only achievable at 24,600ft.

Without MW-50, the Bf 109 K-4’s best performance was 416mph, at 26,528ft. These figures also relate to well-built aircraft running high octane fuel in engines allowed to run at full power. De-rating engines had been a common practice in the Luftwaffe, to reduce maintenance time, since the beginning of 1944. Fuel shortages meant there was no opportunity to thoroughly test engines and aircraft before they were accepted into service either. And by the end of the war, many if not all of Germany’s aircraft manufacturers were relying on slave labour to produce components and assemble the finished product. Sabotage and shoddy workmanship were routine – a situation that worsened as the end of the war approached. Hans Knickrehm of I./JG 3 wrote about the new Bf 109 G-14/AS aircraft received by his group from the manufacturer in October 1944: “The engines proved prone to trouble after much too short a time because the factories had had to sharply curtail test runs for lack of fuel.

“The surface finish of the outer skin also left much to be desired. The sprayed-on camouflage finish was rough and uneven. The result was a further reduction in speed. We often discovered clear cases of sabotage during our acceptance checks. Cables or wires were not secured, were improperly attached, scratched or had even been visibly cut.” These issues were typical of many new aircraft being delivered to German front line units. The available statistics for the aircraft examined here, regardless of their origin, do not include measurements for some of the most important aspects of performance either – such as manoeuvrability, rate of turn, rate of roll or dive speed. For these, anecdotal evidence must suffice.

In addition, several of these aircraft were only available in tiny numbers and so were unable to make any real impact on the outcome of the war – such as the Heinkel He 162 and Focke-Wulf Ta 152. Some types, such as the Me 163 Komet, were of greater value for the fear they instilled in Allied bomber crews and Allied intelligence than for the pitifully small number of aircraft they were actually responsible for shooting down.

Had they been urgently needed, jets such as the Gloster Meteor F.3 and Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star could have been rushed to the front line and brought into action far sooner – hence their inclusion here. Similarly, the Bell P-63 Kingcobra was delivered to the French too late to see combat and was supposedly only used on the Western Front in small numbers by the Soviets. It was available in 1945, however, and did see combat against Luftwaffe types.

The ultimate piston-engined fighters here.

*Note: this article is about aircraft in the European Theatre of World War II in 1945

The aim here is simply to provide a statistical comparison between the most powerful and advanced aircraft available in Europe. Five British types have been chosen for inclusion – the Supermarine Spitfire LF.IX, the Spitfire Mk.XIV, the Hawker TyphoonMk.1b, the Hawker Tempest V and the Gloster Meteor F.3. The four American types are the North American P-51D Mustang, the Republic P-47D Thunderbolt, the Lockheed P-38L Lightning and the Lockheed P-80A Shooting Star.

The four Soviet types are the Lavochkin La-7, the Yakovlev Yak-3, the Yak-9U and the Bell P-63A Kingcobra – an American fighter but initially flown almost exclusively by the Russians. Finally, seven German machines are included: the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A-9, the Ta 152 H-1, the Fw 190 D-9, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 K-4, the Me 262 A-1, the Me 163 B-1 and the Heinkel He 162 A-2.

Some contemporary types, such as the Bell Airacomet, are omitted because they were never considered for front line duties, and others, such as the Hawker Tempest II and de Havilland Vampire, have been left out because they were simply not yet ready for action.

Supermarine Spitfire LF.IX

Later production models of the Spitfire LF IX were fitted with the pointed tail fin that was also a feature of the Spitfire XVI. Production of the Mk.IX continued until the end of the war and it was the most numerous type of Spitfire built.

The Merlin 66-engined Spitfire LF.IX was the workhorse of the RAF’s fighter squadrons from its introduction in 1943 through to the end of the war. The original Mk.IX had been introduced as early as mid-1942.

Compared against a captured Bf 109 G-6/U2 with GM-1 nitrous oxide injection by the Central Fighter Establishment in late 1944, the LF.IX was found to be superior in every respect except acceleration in a dive. Manoeuvrability was found to be “greatly superior” and it was noted that the LF.IX “easily out-turns the Bf 109 in either direction at all speeds”. By 1945, the LF.IX was beginning to show its age. Figures given for its top speed vary but it was undoubtedly among the slowest of the 20 aircraft being assessed here in a straight line. It could out-climb and fly higher than most of its opponents, however, even out-performing many of the most advanced German types.

Flying Officer George Lents of 341 Squadron pictured in front of his Spitfire LF.IX in Sussex, June 1944. By 1945, the Spitfire IX had been completely outclassed in straight line speed by newer types, but it could still climb faster and manoeuvre better than many of its opponents.

There were few to rival it for manoeuvrability either, making it worthy of inclusion here, and explaining why it remained on the front line for so long even when more ‘advanced’ types were becoming available to replace it.

A line-up of Spitfire LF IXs at an advanced landing ground on the Continent in late 1944.

Supermarine Spitfire Mark XIV

The Spitfire XIV sacrificed some manoeuvrability for raw speed but was still capable of out-turning and out-climbing almost any opponent.

Combining the Spitfire Mk.VIII airframe with a two-speed, two-stage supercharged 2220hp Rolls-Royce Griffon 65 engine resulted in the Mk.XIV. Introduced in 1943, in appearance it was similar to the Spitfire XII with normal wings but with a five-bladed propeller. The rudder was also enlarged and an extra internal fuel tank was fitted.

The huge increase in power meant the XIV was a match for most of its piston-engined contemporaries, the only exception being the Ta 152, and the two are believed never to have met in combat. Its range was short and its manoeuvrability was inferior to that of the Spitfire LF.IX, but nevertheless the XIV was one of the best fighters of the war’s final months.

Flight Lieutenant Ian Ponsford, who shot down seven enemy aircraft while flying a Spitfire Mk.XIV with 130 Squadron, remembered: “The Spitfire XIV was the most marvellous aeroplane at that time and I consider it to have been the best operational fighter of them all as it could out-climb virtually anything.”

“The earlier Merlin-Spitfire may have had a slight edge when it came to turning performance, but the Mark XIV was certainly better in this respect than the opposition we were faced with. The only thing it couldn’t do was keep up with the Fw 190 D in a dive.

Over 99.7% of our readers ignore our funding appeals. This site depends on your support. If you’ve enjoyed an article donate here. Recommended donation amount £12. Keep this site going.

“It could be a bit tricky on takeoff if one opened the throttle too quickly as you just couldn’t hold it straight because the torque was so great from the enormous power developed from the Griffon engine.

“One big advantage that we had over the Germans was that we ran our aircraft on advanced fuels which gave us more power. The 150 octane fuel that we used was strange looking stuff as it was bright green and had an awful smell – it had to be heavily leaded to cope with the extra compression of the engine.”

During the Arab-Israeli War in 1948, Israeli pilots flew both Mk. IX and Mk. XIV Spitfires bought from Czechoslovakia against Egyptian Spitfires and concluded that the IX was better due to its superior manoeuvrability.

Sporting a large five-bladed propeller, the Spitfire XIV was tricky on takeoff due to the enormous torque produced by its Rolls-Royce Griffon 65 engine.

Hawker Typhoon Mk.1b

It was uncomfortable to fly but the Typhoon was agile at low level despite being a large aircraft and could carry a heavy weapons load, making it particularly useful as a fighter-bomber.

The history of the Typhoon is too long and troubled to detail in full here, suffice to say that it was a failure in the high-altitude interceptor role for which it was designed. Although it was the RAF’s first fighter capable of more than 400mph, climbing speed was regarded as inadequate and a series of structural failures in the fuselage caused significant delays in its production.

Having entered service in 1941, it is one of the oldest of the 20 aircraft examined here and was beginning to struggle against more advanced competition by 1945. Pilots had to wear an oxygen mask from the moment the engine was switched on due to heavy carbon monoxide contamination in the cockpit, and the level of noise and vibration made life at its controls doubly uncomfortable.

Nevertheless, as history shows, it proved to be a deadly fighter-bomber when armed with rockets or bombs, and many Fw 190 pilots were unpleasantly surprised to discover that despite its size and weight – being one of the largest and heaviest single-engined aircraft here – it had a very short radius of turn and rolled well.

It could also carry a heavy load with relative ease, which meant it could be fitted with four powerful 20mm Hispano Mk II cannon – a weapon originally designed as an anti-aircraft gun – in addition to its bombs/rockets.

Typhoon MN686 was one of Hawker’s development machines, photographed here in late 1944. The Typhoon was fast but poor in a climb.

Hawker Tempest V

Hawker Tempest Vs from 501 Squadron pictured 1944. The Tempest V had a quartet of 20mm cannon, giving it a deadly punch, and at low level was capable of overmatching even the Luftwaffe’s finest fighters.

Big, heavy and fast, this thin-wing upgrade of the Typhoon design was undoubtedly one of the best fighters of the Second World War and at low altitudes could give either of the two Spitfires detailed here a run for its money.

It had the same Napier Sabre IIA engine as the Typhoon but range was extended by moving the engine forward 21in to make room for a 76 gallon fuel tank. Tail surfaces were enlarged and a four-bladed propeller was fitted. While the first 100 built had the Typhoon’s four Hispano Mk II cannon, the Series II Tempest V got the Hispano Mk V cannon – the weapon’s ultimate wartime development. The first Tempests reached squadrons in January 1944 and they were initially used to combat Fieseler Fi 103 V-1 flying bombs. When they were moved on to the Continent, it quickly became clear that below about 8000ft the Tempest dramatically outperformed the very best aircraft that the Luftwaffe could throw at it – such as the Fw 190 D-9 and the Bf 109 K-4. Tempest pilots were also responsible for shooting down a number of Me 262s.

According to Hubert Lange, a pilot who flew 15 missions in Me 262s with JG 51, the Hawker Tempest was the German jet’s most dangerous opponent, “extremely fast at low altitudes, highly manoeuvrable and heavily armed”.

Similar to the Typhoon, the Tempest’s redesigned wing and enlarged tail were big improvements. These 486 Squadron Tempests are pictured at Lübeck shortly after the war’s end.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Save the Hush-Kit blog. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Thank you. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here

Gloster Meteor F.3

The first Gloster Meteors on the Continent during 1945 were painted white to avoid ‘friendly’ fire. The jet’s handling was described as pleasant but it suffered from directional snaking, particularly in poor weather.

Powered by a pair of Rolls-Royce Derwent I jets with a static thrust of 2000lb each, the Meteor F.3 began to enter service in early 1945. Deliveries of its predecessor, the F.1, had begun in June 1944.

While the first Meteors were actually slower than the fastest piston-engined fighters then available, such as the Spitfire XIV, the F.3 offered much higher performance.

It was field tested from bases in Belgium with 616 and 504 Squadrons during the last weeks of the war primarily in the fighter reconnaissance and ground-attack roles. It never met the Me 262 in aerial combat but some were shot down by Allied flak due to their superficial resemblance to the German machine.

As a result, Meteors were given an all-white paint scheme to make them more easily recognisable to friendly units.

Like all in-service jets in 1945, the Meteor was at the cutting edge of performance, and in good weather handling was described as “pleasant”, but the F.3 suffered from ‘snaking’ – directional instability – which made it more difficult to target an aerial opponent effectively. A report from the Central Fighter Establishment noted: “The failure of the Meteor to come within an acceptable standard is due to the directional snaking which occurs in operational conditions of flight so far experienced and the heaviness and consequently slow operation of the ailerons to bring the sight back on to the target.

“This snaking tends to increase with increase of speed and once it has commenced it is impossible to correct it within the limits of time available during an attack.”

Whether this would have proved to be a fatal flaw in actual combat or merely an annoyance to the type’s pilots will never be known.

It says a lot about the fortunes of Britain in the war and the role of the Meteor that a large section of the CFE report is devoted to how difficult it would be to fly in formation. It is impossible to imagine the Germans, desperate to rush their jets into action, bothering to do the same for the Me 262.

A Meteor in flight. The type was Britain’s first operational jet fighter and while its performance on paper was not dramatically dissimilar to that of the Me 262, the Meteor’s handling was probably inferior.

North American P-51D Mustang

Beloved of its pilots, the P-51D was an excellent air superiority fighter, though it was poorly armoured and could be a handful at low level. This is serial number 44-14955 ‘Dopey Okie’ of the 487th Fighter Squadron, part of the 352nd Fighter Group.

Flown in huge numbers while escorting American bombers, the Mustang is widely accepted as having been the USAAF’s most successful air superiority and escort fighter.

In P-51D form its performance was excellent at high altitude. Powered by a Packard-built version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and featuring a bubble canopy, it boasted a good though not sparkling rate of climb and exceptional visibility.

It retained a good measure of agility even above 400mph and was a very stable aircraft with few vices to punish the inattentive. At low altitude and in low speed encounters with enemy aircraft however, its large turn radius became a real disadvantage.

In addition, as a high performance long-range escort, it was lightly built and poorly armoured – rendering it vulnerable to even slight battle damage. Many American pilots using the Mustang for strafing ground targets found that even a light flak hit could be fatal.

In high speed, high altitude encounters, the Mustang was able to reach its full potential and there was little to match it in this, its own stomping ground – as Fw 190 and even Me 262 pilots discovered.

North American P-51D-5-NA Mustang serial 44-13926 serving with the 375th Fighter Squadron. The famous ‘Cadillac of the sky’ was America’s best regarded fighter of the war. It was capable of flying huge distances and performed exceptionally well at high to medium altitude.

Republic P-47D Thunderbolt

P-47D-30 Thunderbolt 44-32760 ‘Shorty Miriam’ of the 354th Fighter Group. The Thunderbolt was a huge, powerful fighter and in the right circumstances could beat the Messerschmitt Me 262. It gave continual mechanical problems, however, and was less able than the P-51D.

Faster and higher flying than even a Mustang, the P-47D Thunderbolt was a big, heavy aircraft – the Tempest to the Mustang’s Spitfire. As such, it could also soak up more battle damage and could carry a heavier weapons load too.

On paper, the Thunderbolt seemed to have the edge over the Mustang, but pilots told a different story. The Mustang was simply more agile – it handled better and was easier to fly well. Against German fighters, the Thunderbolt seems to have been just as effective at all altitudes. In the end, the Thunderbolt lost out simply because fewer were used in situations where they were likely to enter aerial combat with German fighters.

One source gives the total number of enemy aircraft shot down by the P-47 as 3662 compared to the P-51’s 5944. General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland’s Me 262 was shot down by a P-47 Thunderbolt though, not a P-51.

Against the Spitfire XIV, neither the P-47 nor the P-51 could be said to have had a clear advantage. Both were slower, less manoeuvrable at all altitudes and less able to climb at speed – but they had the capacity to keep up with high-flying B-17s and B-24s long after a Spitfire XIV would’ve had to turn for home.

Like the Hawker Typhoon, the P-47 achieved great success as a fighter-bomber, though it was also a superb fighter. Pictured here is P-47D-25 42-26641 ‘Hairless Joe’ of the 56th Fighter Group.

Lockheed P-38L Lightning

The P-38L was used by fighter squadrons of the 1st Fighter Group in Europe. Pilot 2nd Lieutenant Jim Hunt of the 27th Fighter Squadron sits atop P-38L ‘Maloney’s Pony’. The aircraft was never flown by its namesake, 1st Lieutenant Thomas Maloney, because on August 19, 1944, his P-38 (a different one) was forced down on the French coast. While walking along the beach to find help, he trod on a landmine and was badly injured – spending the next three and a half years in and out of hospital.

The oldest of the three piston-engined American fighters featured here, the P-38, had matured by 1945 and had been available in its definitive P-38L form since June 1944.

Its twin engines made it heavy and gave it a very broad wingspan, but since these were set back from the cockpit they also allowed the pilot an excellent view in all directions.

It wasn’t astonishingly fast in a straight line but the Lightning had an exceptional rate of climb. And its counter-rotating propellers meant there was no torque effect in flight and enabled the Lightning to turn equally well to the left or the right. In addition, it had cutting edge features such as power boosted ailerons and electrically operated dive flaps.

However, the Lightning was complicated and pilots had to manage twice the number of engine controls while watching twice the number of gauges. Also it’s armament, while a good average for a late war fighter, was not exceptionally heavy.

It therefore must come last when compared against its American contemporaries.

A Lockheed P-38L Lightning in flight. Thanks to its powerful twin engines, the ‘L’ could climb at an incredible rate and it boasted cutting edge technology – but it was behind the P-51 and P-47 in manoeuvrability.

Lockheed P-80A Shooting Star

Lockheed P-80A-1-LO Shooting Star 44-85004 in flight. The production P-80A was fitted with wingtip fuel tanks which extended its range but resulted in performance-sapping drag.

Just two pre-production YP-80A Shooting Stars saw active service during the Second World War, operating briefly from Lesina airfield in Italy with the 1st Fighter Group. Another two were stationed at RAF Burtonwood in Cheshire for demonstration and test flying.

Powered by a single General Electric J-33-GE-9 jet engine mounted centrally in its fuselage, the Shooting Star was aerodynamically clean and was therefore able to reach an impressive 536mph in level flight at 5000ft – though only when fully painted and without wingtip fuel tanks. In natural metal finish and with those range extending tanks, performance tests carried out by the USAAF’s Flight Test Division showed top speed to be just over 500mph – placing it behind all of its jet-powered contemporaries. Many postwar comparisons of wartime jets have been overly favourable towards the P-80 and tend to take their figures from later, improved versions. The aircraft available during the last four months of the war was somewhat less impressive. Without wingtip tanks, its range was that expected of a short-distance high-speed interceptor – 540 miles – yet with them its range improved but its best rate of climb was down to just 3300ft/min. Armament was six .50 calibre machine guns – the same as that of a Mustang – but these were concentrated in the nose, giving it a more effective fire pattern.

The faster of the two XP-80A Shooting Star prototypes, 44-83021 ‘Gray Ghost’. While this aircraft was given an all-over pearl grey paint job, the other XP-80A, ‘Silver Ghost’, was left in bare metal finish for comparative tests. These showed that just painting the Shooting Star had the effect of increasing its top speed. The P-80 was quicker than Gloster’s Meteor but still failed to beat the Me 262.

Lavochkin La-7

It boasted a powerful radial engine which gave it a performance advantage over older Luftwaffe types but the La-7 was falling behind as the war ended.

Based largely on the earlier La-5 fighter and powered by an air-cooled 1850hp ASh-82FN radial engine, the La-7 incorporated more alloys in place of the original wooden structure. The cockpit got a rollbar, the landing gear was improved and a better gunsight, the PB-1B(V), was installed along with a new VISh-105V-4 propeller and an enlarged spinner to improve streamlining. Unfortunately, the bigger spinner meant less air reached the engine for cooling so a fan was fitted behind it. Visibility was excellent and either a pair or trio of 20mm cannon gave good though not exceptional firepower.

The Soviets at the time honestly believed that the La-7 was the best fighter in the world for dogfighting and it was certainly faster and more manoeuvrable than the older marques of Fw 190 A that it typically faced on the Eastern Front.

In company such as that discussed here, however, it fails to make the grade. The latest and last Fw 190, the D-9, outperformed it in most areas when using MW-50. Small and lightweight, the La-7 had to be flown at low level because it simply couldn’t manage at high altitude. It was available in big numbers though, and that the Germans were simply unable to match.

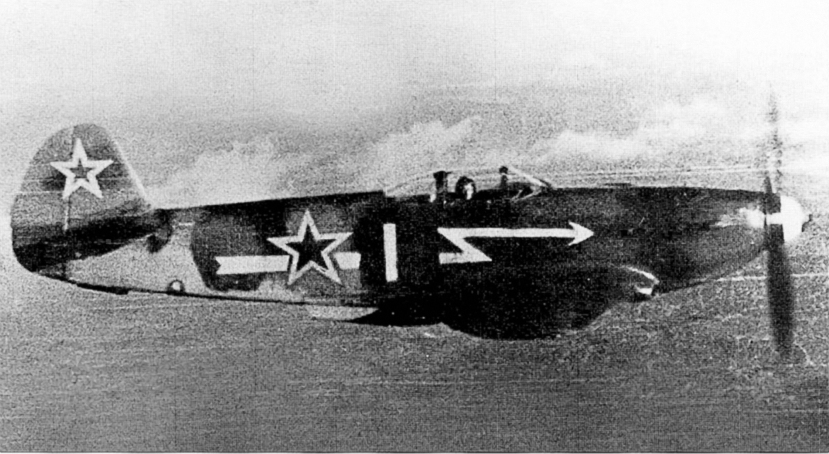

Yakovlev Yak-3

A Yak-3 pictured in Poland during 1945 beside the carcass of a Bf 109. Its high power to weight ratio meant that it handled extremely well with an expert pilot at the controls.

The Russians did their best to develop small lightweight fighters that could be produced in huge numbers and this design philosophy had its greatest success in the form of the Yak-3. Work on it commenced in 1941 but was seriously hampered by first a lack of aluminium and then the German invasion which resulted in design work actually being halted.

As the tide of battle turned, Yakovlev picked up where it had left off and produced the Yak-1M, a lighter, shorter-winged version of the Yak-1. This embodied many technological advances such as a mastless radio antenna, reflector gunsight and better armour. It was meant to have a 1600hp Klimov M-107 V12 engine but this was unavailable and the 1300hp M-105 had to be used instead.

Hush-Kit needs friends to carry on. Become a friend with a small monthly donation to keep us going.

Even with this relatively small powerplant fitted, the redesignated Yak-3 was still 40mph faster than the Yak-9, which despite its name actually entered service first.

The fact that the Yak-3 can be found somewhere towards the bottom of every table associated with this comparison belies its greatest strength – its ability to out-turn both the Bf 109 and the Fw 190 below 20,000ft. Pilots who were new to the Yak-3 found it easy to fly but its true potential was only realised in the hands of an experienced flyer.

Against the best of the Luftwaffe’s machines, performing at their best, the Yak-3 would have been found sorely lacking but it was ideal for low-level skirmishing and could face standard German types on an footing.

The diminutive Yak-3 in flight. The aircraft was primitive in comparison to other nations’ fighters but could still skirmish effectively at low altitude.

Yakovlev Yak-9U

Visibility from the Yak-9U’s cockpit was good and it manoeuvred well at low altitude but its performance was unremarkable compared to its more powerful peers.

The first Yak-9s off the production line were fitted with the same Klimov M-105 as the Yak-3 and being substantially heavier paid a big price in performance. Top speed was just 367mph – about the same as that of a Spitfire Mk.I in 1939.

However, when the Yak-9 was fitted with the Klimov M-107A, which delivered 1650hp, its performance dramatically improved. Like the Yak-3, it offered excellent all round visibility but armament was somewhat lacking – with just a single 20mm cannon firing through its propeller hub and a pair of .50 calibre machine guns mounted in its engine cowling.

Like the La-7 and the Yak-3, the Yak-9U did its best work at low altitude. It was heavy only when compared to the Yak-3 and even with the more powerful M-107A it could still be considered underpowered in this company. It was manoeuvrable and had better armour than the Yak-3 but it was still no match for the likes of a Fw 190 D-9 or a Bf 109 K-4 on a good day.

A Yakovlev Yak-9U of the 151st Guard Air Fighter Regiment at Yambol in Bulgaria. The original Yak-9, fitted with a Klimov M-105, was a poor performer, but once it had the Klimov M-107A it joined the front rank of fighters available in 1945.

Bell P-63A Kingcobra

Row upon row of P-63 Kingcobras lined up at the Bell factory prior to delivery to the Soviet air force.

The Americans did not think too highly of Bell’s Kingcobra. They had thought even less highly of its predecessor, the Airacobra, largely because it had been designed to fly with a turbosupercharger but was put into production without one.

The Soviets, however, who received hundreds of Airacobras from the Americans on a lend-lease basis, rather liked it. Much has been written about the Airacobra’s strengths as a ground-attack aircraft, even though the Soviets themselves never regarded it as such and tended to use it for air-to-air interception missions instead.

The Kingcobra saw the turbosupercharger finally installed and the overall design modified to incorporate technological advancements – such as laminar flow wings, a redesigned tail and a four-blade propeller. The first XP-63, a converted XP-39E, was first flown on December 7, 1942.

From the outset, the Soviets were involved in the development process to the extent of supplying personnel to fly the prototypes at Bell’s factory.

Overall Kingcobra production ran to 3303 examples and 2397 of them were supplied to the Soviet Union. No Kingcobra ever saw combat with a USAAF squadron, which is not surprising since the P-63’s range was limited and its performance was poor at high altitude – making it useless as an escort fighter.

The ultimate piston-engined fighters here.

At low level, however, where the Soviet fighter pilots flew, it was effective. Like the other high performance fighter aircraft flown by the Soviets, its top speed and rate of climb were by no means sparkling but it was highly manoeuvrable below 8000ft.

Pilots of the Soviet 66th Fighter Wing take a break beside their Bell P-63s. More than two-thirds of all Kingcobras built went to the Russians.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A-9

The Fw 190A was the fastest production fighter aircraft in the world when it first appeared in 1941. Once overheating problems with its powerful BMW 801 engine were largely overcome, it joined the Bf 109 as one of the Luftwaffe’s two front line fighters.

The Fw 190A was the fastest production fighter aircraft in the world when it first appeared in 1941. Once overheating problems with its powerful BMW 801 engine were largely overcome, it joined the Bf 109 as one of the Luftwaffe’s two front line fighters.

In 1944, with the streamlining of German aircraft production, unprecedented numbers of Fw 190s were churned out, mostly in A-8 form. All the while, BMW had been attempting to improve its engine design with little success.

Unfortunately the company had succeeded in producing an engine that had very little development potential. The standard Fw 190 engine was the BMW 801 D-2 and the firm’s engineers were aiming for a model they called the 801 F. This, though, was taking years to perfect – years that Germany didn’t have.

Therefore some of its components were fitted to the standard engine as an interim measure. First these were used to create the 801 U, which had 1730hp at 2700rpm at sea level, compared to the standard D-2’s 1700hp. Then they managed to use more components, creating the 801 S or TS, with a much more impressive 2000hp.

It was this engine which was fitted to a largely unmodified Fw 190 A-8 airframe to create the type’s final form – the Fw 190 A-9. The first production model appeared in August 1944 and production continued until the end of the war.

BMW was heavily bombed towards the end of the war, reducing production of the 801 S to a snail’s pace so fewer than 1000 A-9s were built. In combat, the Fw 190 A-9 gave its pilots a greater edge over their Soviet adversaries but the Allies’ machines were still markedly superior.

Its performance at high altitude was poor, the Fw 190’s rate of turn was never a match for that of the Spitfire and even the aircraft’s exceptional roll rate and dive speed was being cancelled out by the raw power of types such as the Spitfire XIV.

Unlike the Spitfire IX, the Fw 190 A was largely obsolete by 1944 but the Germans had little choice but to keep on producing it since so many assembly lines had been geared up for it and every fighter was sorely needed.

The Fw 190 A-9’s BMW 801S (TS) engine was a compromise but still produced a respectable 2000hp. Note the bubble canopy and the broad paddle blades of the VDM-9 propeller on this example.

A Fw 190 A-9 leads a line-up of captured Focke-Wulf machines shortly after the war’s end. The A-9 might have been produced in greater numbers had BMW not been so heavily bombed. As it is a lack of production figures for 1945 means it will never be known precisely how many were made.

Focke-Wulf Fw 190 D-9

The Fw 190 D-9 was regarded by those who flew it and those that flew against it as a development of the Fw 190 A. In fact, it was simply Focke-Wulf’s attempt to provide an alternative engine for the Fw 190 airframe in case the supply of BMW units was disrupted. This example, WNr. 210051, has just rolled off the production line at Bremen-Neuenlanderfeld. It was later delivered to III./JG 54

German pilots were largely thrilled by the performance of the Fw 190 D-9 – a stretched Fw 190 A powered by the Junkers Jumo 213 A-1 which could be boosted up to an output of 2000hp with MW-50 injection.

The ‘long nose’ D-9 lost some of the Fw 190 A’s handling and manoeuvrability as the trade-off for its increased speed however.

Focke-Wulf designer Kurt Tank never intended the D-9 to be the next step in the Fw 190’s evolution however – that was the Ta 152 – instead he was on record as saying that the existing airframe simply needed an alternative powerplant since BMW’s factories were being so heavily targeted by Allied bombing.

There has been some suggestion that without water-methanol injection, the D-9’s top speed was around 390mph. The Soviets who tested examples they captured intact but without MW-50 were certainly deeply unimpressed by the performance of its Jumo 213 A engine. The long nose restricted forward and downward visibility, which became a problem because the aircraft had a high wing loading – its wings were the same as those used on the A-8 – and it therefore needed a fast landing and stalled easily. Having to put the aircraft down fast and being unable to see where you were going was a bad combination. Even so, German pilots still considered the D-9 easier to land and take off in than any Bf 109 variant due to its wide-track landing gear.

Armament was a pair of wing-mounted 20mm cannon and two .50 calibre machine guns in the engine cowl – not outstanding but still sufficient, particularly against lightly armoured opponents such as the Soviet types.

An early production Fw 190 D-9 stands out in the snow prior to delivery to III./JG 54, the first unit to operate the type, in September 1944. In combat, the D-9 was fast with MW-50, particularly in a dive. Its performance surpassed that of the Fw 190 A types but Allied types such as the Mustang still eclipsed it.

Focke-Wulf Ta 152 H

Focke-Wulf Ta 152 H W.Nr. 110003 of JG 301 as it appeared having been captured by the Allies and shipped to America with the Foreign Equipment number 112. The abilities of the Ta 152 H remain difficult to assess since so few were made. On paper it was, perhaps, the best piston-engined fighter of the war.

The Ta 152 was effectively brought into being on the same day that its predecessor the Ta 153 was cancelled – at meeting on August 13, 1943. Tank suggested at the meeting that the same benefits of the Ta 153, which was almost entirely a new machine, could be achieved by simply extending the wings and fuselage of the existing Fw 190 airframe with inserts. The Ta 152 would be only 10% new and as such was approved for development. The Fw 190 D-9 was an even simpler conversion.

Bringing the Ta 152 to production took longer than expected due to delays in the development of the engines that were to power it. In the end, the Ta 152 C standard fighter version only reached the prototype stage and just a handful of high-altitude Ta 152 Hs were built and saw combat.

Powered by the long-delayed but finally sorted supercharged Junkers Jumo 213 E-1 engine, the 152 H was the fastest piston-engined aircraft to see combat during the war by a considerable margin. It also had a decent rate of climb, the highest ceiling of any piston-engined fighter of the war and a remarkable wingspan of 47ft 4½in.

Even its armament was good – two 20mm cannon in the wings and a single 30mm cannon in the nose – though in practice problems were encountered with jamming. There was no chance of development work to resolve the issue since by this stage the factories that built the Ta 152 H had already been overrun by Soviet troops.

Precisely how manoeuvrable the production Ta 152 H-1 was is largely based on speculation. After the war its surviving pilots defended its reputation to the hilt – standing by their claim that it was better than almost anything else in the sky by the end of the war.

Top 10 fighters of World War II here.

However, there are no flying examples available today and even while the type was briefly in service it was prone to sudden and mysterious failures which on a couple of occasions resulted in the death of the pilot.

It seems to have enjoyed mixed fortunes in combat against the excellent Hawker Tempest V and somewhat more success against Yak-3s but it never faced a Mustang or Thunderbolt in their high altitude area of operations, as far as is known. If it had done, it might have faced them on at least an equal footing.

Messerschmitt Bf 109 K-4

Messerschmitt Bf 109 K-4 WNr. 330130 at a Messerschmitt factory during the autumn of 1944. In all round performance the K-4 surpassed the final development of its great rival, the Fw 190 A-9, but still suffered from its antiquated narrow track undercarriage and small wings.

The final production version of the long-serving Bf 109 design was the K-4. The first production examples of the type, conceived in the mid-1930s as a lightweight highly manoeuvrable fighter, flew in 1937, making it easily the oldest type here.

The Bf 109 that saw a vast increase in production alongside the Fw 190 A-8 was the Bf 109 G-6 and later versions were produced in progressively smaller numbers. Shortly before the war’s end, Willy Messerschmitt had been preparing his company to wind up production of the 109 in preparation for a wholesale switch to the Me 262 and its projected successors.

The K-4 was an attempt to give the basic design a cleanup using all the available technological advances to produce something close to the ultimate Bf 109. It was also a move intended to remove the need for the bewildering variety of sub-variants spawned as part of the Bf 109 G series.

Further K series 109s were projected beyond the K-4 but none made it to production.

The K-4’s cockpit canopy was altered to the less-heavily framed Erla/Galland design to provide improved visibility and a powerful Daimler-Benz DB 605 DC engine was installed, producing 1800hp during takeoff, rising to an incredible 1973hp with MW-50. This in an aircraft that was lighter than any of the lightweight Soviet designs.

At its best, the Bf 109 K-4’s performance figures were nothing short of astounding. Its boosted top speed of 440mph put it in the same league as the Spitfire XIV and P-51 Mustang, and a climb rate of 4500ft/min was among the very best.

Armament was a problem, however. The K-4’s standard load was a 30mm MK 108 firing through the propeller hub and a pair of MG 131 .50 calibre machine guns mounted in the engine cowling. There were difficulties in getting the MK 108 to work properly in this configuration though which meant that the gun jammed easily if attempts were made to fire it while manoeuvring.

In practice, many Bf 109 K-4s reached the front line without their MW-50 kits fitted or with some other defect whether as a result of deliberate sabotage or simply poor craftsmanship on the part of the forced labourers who built many of their components. The type was therefore seldom able to reach its dazzling full potential in combat.

The ultimate development of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 to actually reach front line service was the K-4. It was a remarkable upgrade of the type but was often let down by shoddy workmanship and sabotage. This one is WNr. 330230 ‘White 17’ of 9./JG 77 at Neuruppin in November 1944.

Messerschmitt Me 262 A-1

The Me 262 took years to develop but the end result, when its engines had been freshly reconditioned and everything was working correctly, was spectacular. Pictured here is Me 262 A-1 ‘White 4’ of JG 7 at Achmer in Germany towards the end of 1944.

The Me 262 was the first operational jet fighter anywhere in the world when it equipped Erprobungskommando 262 and then KG 51 in May-June 1944 and began to enter combat against Allied aircraft.

Some American writers such as Robert F Dorr have attempted to advance the claim of the Bell P-59A Airacomet to being the first operational jet fighter – since it entered ‘service’ in late 1943, but in practice this was little more than part of the development process. The Me 262 was a high performance combat machine that could outrun anything short of a rocket-powered Me 163, was armed with four 30mm cannon and potentially R4M air-to-air rockets – making it the most heavily armed aircraft here – and could handle sufficiently well to make good use of its other virtues.

Its design was futuristic – those swept-back wings were revolutionary – and a lengthy period of development before it entered even service testing meant many, though by no means all, of its early foibles had been worked out and eliminated.

In combat it was by no means indestructible and its engines had only a very limited operational lifespan before they needed to be removed and overhauled. Its nosewheel was notoriously weak, acceleration was slow, landing speed was high and the aircraft was so fast in combat that pilots unfamiliar with jets – in other words most of its pilots – struggled to hit their targets.

But still, the Me 262 was a deadly opponent for any Allied fighter. It could be outmanoeuvred by a Spitfire but it was very difficult to catch. Even its cruising speed, 460mph, was above anything the Allies could match except in a dive.

It has been endlessly opined that had the Me 262 been built in much larger numbers – or fractionally sooner – the war might have had a different outcome, but in reality it was at the very edge of what was technologically possible for 1945 and its engines were the source of its worst problems. They simply could not be made good enough fast enough.

The first jet fighter to begin combat operations anywhere in the world, the Me 262, was an engineering masterpiece and remains a design icon. Not only that, it was also an excellent fighter. One of the best known Me 262s, the unpainted WNr. 111711, was surrendered to the Americans by Messerschmitt company pilot Hans Fay at Rhein-Main airfield on March 30, 1945.

Messerschmitt Me 163 B-1

Filled with volatile explosive chemicals that provided enough thrust for only seven and a half minutes of powered flight and lacking even a proper undercarriage once it had been glided back to the airfield, the Me 163 was as much a danger to its pilots as it was to the enemy.

The first rocket-powered aircraft in the world was the tailless Ente or ‘duck’ – a glider designed by Alexander Lippisch powered by an engine produced by rocket pioneers Max Valier and Friedrich Sander at the behest of car company publicist Fritz von Opel.

After Opel left Germany in 1929 and Valier was killed in 1930, Lippisch went to work for the DFS – the German glider research organisation. Here he produced several revolutionary tailless designs and in 1940 these were fitted with a powerful liquid rocket engine designed by Hellmuth Walter, the HWK 109-509, and the Messerschmitt Me 163 was created.

The tiny lightweight interceptor had two ‘fuel’ tanks, one filled with a methanol, hydrazine hydrate and water mixture known as C-Stoff and the other with a high test peroxide known as T-Stoff. When combined, these volatile liquids produced a powerful jet or sometimes a catastrophic explosion.

This was enough for just seven and a half minutes of powered flight, although during that time the aircraft could reach a speed of nearly 600mph and an altitude of nearly 40,000ft. This performance put every other Second World War aircraft in the shade but it was also the Me 163’s undoing as a fighter.

It was armed with a pair of 30mm MK 108 cannon – sufficient to destroy any aerial target, bomber or fighter, with only a couple of hits – but the Komet closed so rapidly on its target that it was very difficult for the pilot to hit anything. There was usually only enough time and fuel for a couple of passes at enemy bombers before the Me 163 was forced to begin its unpowered glide back to base – often at the mercy of Allied fighters. For all its years in development, the deaths of several of its pilots and the huge efforts required to maintain it in service, the Me 163 is believed to have achieved only nine aerial victories.

Heinkel He 162 A-2

Most photographs fail to capture just how small and light the He 162 was – this image of a captured one taking off at Muroc Flight Test Base, California, shows the test pilot, Bob Hoover, looking surprising large in relation to the machine.

More so than the Me 163 – which had actually been in development when the Third Reich was at its peak – the Heinkel He 162 was a product of desperation.

Its overall layout was informed by experiences of the Me 262, with its single BMW 003 jet mounted above the fuselage so that when it crashed the precious engine had a better chance of survival. In addition, its major structural elements were made mostly out of wood.

An ejection seat was fitted but this was ineffective at low altitude. Design work was started by Heinkel as the P 1073 in July 1944 and submitted as the company’s attempt to meet an RLM requirement for a cheap jet that was easy to build and easy for a novice to fly, a people’s fighter, or Volksjäger, two months later. Once it was declared successful on September 23, 1944, the Heinkel design was modified and rushed into production. The first test flight took place on December 6, and efforts to bring it into front line service were being made as the war ended.

The He 162 had a hidden problem however. The design should have used Tego film plywood glue – which was in common use with other German aircraft types – but the factory that made it at Wuppertal was destroyed in an RAF bombing raid and an alternative was needed to ensure He 162 production could go ahead.

The replacement glue, unbeknownst to Heinkel, had a gradual corrosive effect on wood and the He 162s that were produced began to suffer from mysterious structural failures. It didn’t help that the BMW 003 wasn’t ready for service either and was prone to flameouts.

When the He 162 was working properly and not falling apart in the sky, pilots regarded it as an excellent aircraft with light controls that was stable at high speed. While its speed couldn’t match that of the Me 262, or even the Meteor F.3, it could out-climb either of them.

Its armament of two MG 151/20 autocannon was relatively light but the small aircraft simply wasn’t up to housing the twin MK 108s originally projected.

Given more time and better glue, the He 162 might conceivably have been a contender but in the event it was a non-starter.

The very first He 162 V1, W.Nr. 20001. When it remained in one piece, the He 162 was a fine fighter aircraft, yet it still matched the speed and hitting power of the Me 262.

So which was the best?

From among the 20 aircraft examined here, there are some obvious dropouts when it comes to deciding which was best. The British Hawker Tempest V was a better fighter than the Typhoon, so the latter can be safely ruled out.

The same applies to the Focke-Wulf Ta 152 and both of the Fw 190 A types. The A-9 and the D-9 can be ditched. Similarly, the Me 262 would have been the better fighter even if the He 162 could have been made to work flawlessly so the notorious Volksjäger has got to go. The Me 163’s endurance was too brief to make it an effective fighter so it can also be taken out of contention.

The slowest of the American types was the P-38 Lightning. It climbed well but was surpassed as a dogfighter, therefore it too has to go. Though they were good at low-level fighting they were not superior to the most exceptional of their contemporaries so all four of the Soviet types can be excluded too.

This leaves a top 10 of the Tempest V, Spitfire IX and XIV, Meteor F.3, P-47 Thunderbolt, P-51 Mustang, P-80 Shooting Star, Me 262 A-1, Ta 152 and Bf 109 K.

The non-operational Meteor F.3 and P-80 can probably be ruled out due to ongoing development issues, the Bf 109 K could not be said to have surpassed the Ta 152 in performance, the P-47 Thunderbolt was less manoeuvrable than the P-51 and the Spitfire IX lacked the raw speed to keep up with the new German jets, so a reasonable top five would be the Tempest V, Spitfire XIV, P-51 Mustang, Me 262 A-1 and Ta 152.

Here the narrowing down gets more difficult. The Ta 152 was designed as a high altitude fighter and relied heavily on its complex engine to give it its amazing turn of speed. Its guns were prone to jamming and its reputation rests on only a handful of accounts by decidedly partisan witnesses. It ought therefore to be excluded.

The Tempest V was fast and deadly but it lacked performance at high altitude and straight line speed. Would it have been able to best a Spitfire XIV in a dogfight? Maybe, maybe not.

The choice really comes down to three machines – the Spitfire XIV, the P-51 Mustang and the Me 262 A-1. All three were potent dogfighters, loved by their pilots and feared by their enemies. The P-51 was the best aircraft in the world for its particular role – escorting bombers over long distances at high altitude – but was it the best fighter of the three finalists?

It lacked the speed of either the Spitfire or the Messerschmitt and its rate of climb was significantly below that of the other two. Its manoeuvrability was excellent but it did not surpass that of the Spitfire.

The Me 262 represented the future of air combat. It could outrun almost anything and its armament was second to none – yet it had serious problems in operational service.

Built by dedicated German engineers rather than slaves, flown in numbers from well-defended airfields and kept well supplied with fuel and fresh engines, it would undoubtedly have had the edge over the Spitfire, but in reality Germany’s war situation coupled with its own design flaws served to handicap the world’s first truly successful jet fighter.

In the final analysis, there have to be joint winners – the British Supermarine Spitfire XIV and the German Me 262. The Spitfire Mk.XIV was faster than any other piston engine aircraft bar the Ta 152, its manoeuvrability was outstanding, it could perform exceptionally at any altitude and its rate of climb was stupendous. Its short range made it unsuitable for escort missions but in a straight fight it was simply very hard to beat. Nevertheless, in one-on-one combat, a Spitfire Mk.XIV pilot would have found it very difficult to best a Me 262 – particularly with the latter able to fly 93mph faster. The Spitfire pilot would have enjoyed greater horizontal manoeuvrability and acceleration but would still have had to surprise the Me 262 or the Me 262 pilot would have had to make a fatal error.

After the war, former Luftwaffe General of Fighters and Me 262 pilot Adolf Galland said: “The best thing about the Spitfire XIV was that there were so few of them.”

Claimed top speed

1. Me 163 B-1 596mph

2. Me 262 A-1 540mph

3. P-80A Shooting Star 536mph

4. Meteor F.3 528mph

5. He 162 A-2 522mph

6. Ta 152 H-1 462mph

7. Spitfire Mk.XIV 447mph

8. P-47 Thunderbolt 443mph

9. Bf 109 K-4 440mph

10. P-51 Mustang 437mph

11. Tempest V 432mph

12. Fw 190 D-9 428mph

13. La-7 418mph

14. Yak-9U 417mph

15. P-38L Lightning 414mph

16. Typhoon 1b 412mph

17. P-63 Kingcobra 410mph

18. Spitfire LF.IX 409mph

19. Fw 190 A-9 404mph

20. Yak-3 398mph

Ceiling

1. Ta 152 H-1 49,540ft

2. Meteor F.3 46,000ft

3. P-80A Shooting Star 45,000ft

4. P-38L Lightning 44,000ft

5. Spitfire Mk.XIV 43,500ft

6. P-47D Thunderbolt 43,000ft

7. P-63A Kingcobra 43,000ft

8. Spitfire LF.IX 42,500ft

9. P-51D Mustang 41,900ft

10. Bf 109 K-4 41,000ft

11. Me 163 B-1 39,700ft

12. He 162 A-2 39,400ft

13. Fw 190 D-9 39,370ft

14. Me 262 A-1 37,565ft

15. Tempest V 36,500ft

16. Fw 190 A-9 35,443ft

17. Typhoon 1b 35,200ft

18. Yak-3 35,000ft

19. Yak-9U 35,000ft

20. La-7 34,285ft

Rate of climb

1. Me 163 B-1 31,000ft/min

2. Spitfire Mk.XIV 5100ft/min

3. Spitfire LF.IX 5080ft/min

4. La-7 4762ft/min

5. P-38L Lightning 4750ft/min

6. He 162 A-2 4615ft/min

7. Bf 109 K-4 4500ft/min

8. Tempest V 4380ft/min

9. Yak-3 4330ft/min

10. Fw 190 D-9 4232ft/min

11. P-80A Shooting Star 4100ft/min

12. Meteor F.3 3980ft/min

13. Ta 152 H-1 3937ft/min

14. Me 262 A-1 3900ft/min

15. Fw 190 A-9 3445ft/min

16. Yak-9U 3280ft/min

17. P-47D Thunderbolt 3260ft/min

18. P-51D Mustang 3200ft/min

19. Typhoon 1b 2740ft/min

20. P-63A Kingcobra 2500ft/min

Range (without external drop tanks)

1. P-51D Mustang 950 miles

2. P-47D Thunderbolt 800 miles

3. Ta 152 H-1 745 miles

4. Tempest V 740 miles

5. Me 262 A-1 646 miles

6. He 162 A-2 602 miles

7. Fw 190 A-9 569 miles

8. P-80A Shooting Star 540 miles

9. Fw 190 D-9 520 miles

10. Typhoon 1b 510 miles

11. Meteor F.3 504 miles

12. Spitfire Mk.XIV 460 miles

13. P-38L Lightning 450 miles

14. P-63A Kingcobra 450 miles

15. Spitfire LF.IX 434 miles

16. Yak-9U 420 miles

17. La-7 413 miles

18.Yak-3 405 miles

19. Bf 109 K-4 404 miles

20. Me 163 B-1 25 miles

BOXOUT 5>

Wingspan

1. P-38L Lightning 52ft

2. Ta 152 H-1 47ft 4½in

3. Meteor F.3 43ft

4. Typhoon 1b 41ft 7in

5. Me 262 A-1 41ft 6in

6. Tempest V 41ft

7. P-47D Thunderbolt 40ft 9in

8. P-80A Shooting Star 38ft 9in

9. P-63A Kingcobra 38ft 4in

10. P-51D Mustang 37ft

11. Spitfire Mk.XIV 36ft 10in

12. Spitfire LF.IX 36ft 8in

13. Fw 190 A-9 34ft 5in

14. Fw 190 D-9 34ft 5in

15. Bf 109 K-4 32ft 9½in

16. La-7 32ft 2in

17. Yak-9U 31ft 11in

18. Yak-3 30ft 2in

19. Me 163 B-1 30ft 7in

20. He 162 A-2 23ft 7in

BOXOUT 6>

Empty weight

1. P-38L Lightning 12,800lb

2. Meteor F.3 10,517lb

3. P-47D Thunderbolt 10,000lb

4. Tempest V 9250lb

5. Typhoon 1b 8840lb

6. Ta 152 H-1 8640lb

7. P-80A Shooting Star 8420lb

8. Me 262 A-1 8366lb

9. Fw 190 D-9 7694lb

10. P-51D Mustang 7635lb

11. Fw 190 A-9 7055lb

12. P-63A Kingcobra 6800lb

13. Spitfire Mk.XIV 6578lb

14. Spitfire LF.IX 6518lb

15. La-7 5743lb

16. Yak-9U 5526lb

17. Yak-3 4640lb

18. Bf 109 K-4 4343lb

19. Me 163 B-1 4200lb

20. He 162 A-2 3660lb

This article was an extract from Spitfires over Berlin, thanks to author Dan Sharp

Over 99.7% of our readers ignore our funding appeals. This site depends on your support. If you’ve enjoyed an article donate here. Recommended donation amount £12. Keep this site going.

- Top 10 Cancelled British Fighters

- Dassault Rafale M versus F/A-18E/F Super Hornet: carrier fighters compared

- ‘Madame MiG’: The bizarre story of supersonic pilot and UFO hunter Marina Popovich

- Everything you need to know about Green aviation technology in 2 minutes

- Valentina Tereshkova – The First Woman In Space.

- Campaign for Ukrainian MiG-25 for UK museum?

- 10 most important military aircraft in service today

- Flawed Concepts: a Litany of Failed British Aircraft

Yak-3 fighters were involved in a deadly air clash with P-38 Lightning twin-engined fighters

over the Balkans during the later part of WW2. Google ‘ Air battle over Nis ‘ for the story.

Interesting and thoughtful attempt at a ‘best list’.. However just taking one comparison example- the P-51B/D vs P-47D (all dash no.).

Only the P-47M exceeded the P-51D at MP and WEP for straight level speed and climb. For both full internal combat load out and for ‘fighter condition’ of 1/2 internal fuel, the Mustang was faster and ROC higher than all models of the P-47D. Combined with tighter turn, equivalent roll nd same dive, The P-51B/C/D was a superior fighter vs fighter. One last point, the P-47M was a contemporary of the P-51H.

Only at extreme altitudes >30K was the P-47D approaching P-51B/D performance.

Another thought for consideration – the Mustang lost more pilots strafing in the ETO, but consider that strafing VCs were nearly 2x over the P-47D, and that most airfields were the strafing targets ranging from mid to eastern GY, one must consider that range may have played a role in a % of the losses to ground flak. The Mustang and Corsair had near equivalent loss/sortie rates in Korea to raise questions simply based on Radial vs In-line vulnerability..