Top 10 Cancelled British Fighters

From the dawn of the aeroplane until the 1960s, Britain produced world-class fighter aircraft. As well as the designs that actually felt the air beneath their wings, there is a tantalising treasury of designs that never made it. Here are ten of them.

10. British Aerospace P.125 ‘Have Not Glass’ (1985)

The long history of British expertise in stealth technology has not been discussed a great deal. Britain pioneered radar absorbent material for aircraft, worked on reduced radar observability for nuclear warheads in the early 1960s and was able to create a world class stealth testbed in the Replica model. Prior to Replica, in the 1980s, Britain was working on an aircraft concept so advanced it was classified until 2006.

The BAe P.125 study was for a stealthy supersonic attack aircraft to replace the Tornado. It was to be available in both a short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) and a conventional variant. The conventional variant would feature a central vectored nozzle, the STOVL version would have three vectoring nozzles. In some ways the P.125 was more ambitious than the F-35, the aircraft was to have no pilot transparencies, with the reclined pilot immersed in synthetic displays of the outside word.

It is likely that this formidable interdictor would have been even less visible to radar than the F-35 (though the absence of planform alignment is noteworthy). Despite its 1980s vintage many of its low observable features are reminiscent of today’s latest fighters – others such as its unorthodox wing design, are unique. The project was quietly dropped when Britain joined the JSF programme in the 1990s.

It is likely that the absence of a cockpit transparency on the P.125 was to protect the pilot from laser dazzle weapons (a weapon inaccurately feared to be in widespread use by the Soviet Union). Even now a synthetic cockpit is considered a daunting technological prospect, why BAe didn’t opt for an unmanned configuration remains something of a mystery.

9. British Aerospace P.1214 ‘Bond’s X-wing’ (1980)

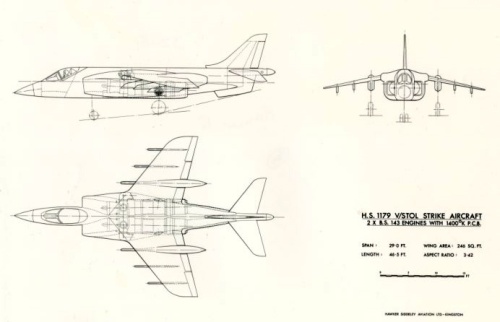

The Pegasus engine with its steerable thrust blesses the Harrier with the ability to take-off and land vertically — and even fly backwards. Unfortunately you can’t put conventional afterburners on a Pegasus engine; there are several reasons for this – the hot and cold air is separated, the inlets do not slow the airflow sufficiently for serious supersonic flight, and the jet-pipes would be too short- and it would also set fire to everything (it was tried from the 1960s and proved problematic). This is a shame as a Harrier is desperate for thrust on take-off and could do with the ability to perform a decent high-speed dash. Though conventional afterburners are out of the question, you could however use plenum chamber burning (PCB). This technology was developed for the Mach 2 Hawker Siddeley P.1154 (think the lovechild of a Harrier and a F-4, with the wingspan of a Messerschmitt Bf 109) – which never entered service. PCB chucks additional fuel into a turbofan’s cold bypass air only and ignites it (a conventional afterburner puts the burning fuel into the combined cold and hot gas flows). This is great, but how do you incorporate this into swivelling nozzles without destroying the rear fuselage with heat and vibration? BAe thought it found the answer – get ride of the rear fuselage altogether, and mount the tail onto two booms. Worried that this already eccentric idea might seem too conventional, BAe decided to add an ‘X-wing’ configuration with swept forward wings (which were in vogue in the early 1980s). This did produce the coolest fighter concept of the 1980s, even in the -3 variant shown which had conventional tails.

The P.1214 would have been extremely agile (and short-ranged), probably comparable to the Yak-41. The P.1214 lost its swept forward wings when further studies revealed them to be of no great value. It now became the P.1216, which was intended to satisfy the USMC and RN’s desire for a supersonic jump-jet (a need eventually met by the F-35B). A full-sized wooden P.1216 was built to distract Thatcher from stealing children’s milk, predictably (as it was British) the whole project was scrapped. This was arguably a good thing as British military hardware testing and development was at its lowest ebb in the 1980s (see the Nimrod AEW.3, SA80 battle rifle, Foxhunter radar, Harrier GR5 compared to the US AV-8B, etc for details).

Supersonic aircraft have their jet exhausts at the back, and there is a simple reason for this: anything in the way of the jet efflux will be exposed to a destructive barrage of heat and vibration. This presents a problem to supersonic STOVL designs wishing to use vectored thrust — to have sufficient thrust and acceleration jet flow far hotter than the Harrier’s is required. One way to solve this is to have no rear fuselage.

8. Saunders-Roe SR.A/1 ‘The Squirt Queen’ (1947)

The aircraft was first proposed in mid-1943, the combination of jet engine speed and the flexible basing options of a flying-boat being regarded as advantageous in the Pacific theatre. Development lagged, and the aircraft did not fly until 16 July 1947. Three aircraft were built, two of which crashed. The simultaneous development of the Princess contributed to the slow development of the SR.A/1, and this was compounded by the decision of Metropolitan-Vickers to cease turbojet engine production.

SR.A/1: Although exhibiting quite sprightly performance, by the time it had flown, the Pacific war was over, and no requirement for the aircraft existed. In addition, the Fleet Air Arm was operating numerous aircraft carriers, and the development of capable jet-powered carrier-based aircraft allowed power projection without the need for airfield construction. Additionally, of course, the large number of airfields constructed during the war also provided many basing opportunities for conventional land-based aircraft.

— Jim & Ron Smith, full article here

7. Saunders Roe SR.53 (1957)

Fast…but outpaced by changes in the threat, and in government policy.

The Saunders Roe SR53 was proposed to meet a requirement for a point-defence interceptor capable of climbing to 60,000 ft in two minutes and 30 seconds. The driver for the requirement was concern about the threat posed by Soviet bombers armed with nuclear weapons.

The SR53 was a compact, delta-winged mixed power aircraft with 1,640 lbst Rolls-Royce Viper jet engine and 8,000 lbst de Havilland Spectre rocket. The armament was intended to be the Blue Jay infra-red air-to-air missile. The operational concept was to climb to altitude using the rocket motor, accelerate up to a maximum speed of Mach 2.2, complete a ground-guided interception, and then return to base using the jet engine.

The contract to develop the aircraft was signed on 8 May 1953. Although Saunders-Roe’s initial schedule called for a first flight in July 1954, development of the aircraft and its rocket motor took longer than expected, and first flight did not occur until 16 May 1957, with the second prototype following in December of the same year. The aircraft was reported as pleasant and easy to fly. The second aircraft was lost in a fatal aborted-take-off accident in June 1958, and the program was eventually cancelled in July 1960, after 56 test flights. The highest speed reached in the flight test program was Mach 1.33.

During the seven year development and flight programme, a great deal of change had occurred in aerospace capabilities: jet engine development had produced high power, reliable engines; radar had improved its ability to detect targets at long range; the Soviets had moved towards the development of stand-off weapons; and surface-based guided missiles had improved in capability. These technical advances had the effect of invalidating the operational concept for the aircraft. In future, it would be possible, and necessary, to defeat threats at a greater distance, before the release of nuclear stand-off weapons, and there was no way a short-range point-defence interceptor such as the SR53 could achieve this. Furthermore, the first flight of the aircraft occurred just two months after the Duncan Sandys 1957 Defence White Paper, which suggested new manned aircraft were no longer required for air defence, and that surface-based air-to-air missiles would in future fill this role. The first flight of the SR 53, just after this policy announcement, could not have been more badly timed, but the operational concept had already been superseded.

Top 10 cancelled French aircraft here

The programme left no direct legacy. Air defence has evolved through point defence interception, to barrier combat air patrols, and to beyond-visual-range engagements using air-to-air missiles, supported by distributed and networked sensors. Low signature capabilities and geo-political instabilities are pushing air defence in the direction of cooperating manned and unmanned aircraft, armed with long-range weapons, and supported by distributed and networked sensors.

— Jim & Ron Smith, full article here

6. Thin Wing Javelin ‘Terrific Tripe Triangle’ (1953)

The much maligned Javelin got everything right apart from the aerodynamics — and it could easily be argued that if a major war had started in the early 1960s it might have given a better account of itself than the venerated Lightning. The Javelin had space for a large radar, a good range, powerful engines and twice the air-to-air weapon load of its English Electric successor. It also had twice the crew – an important consideration considering the difficulties in flying, navigating and operating the weapons systems of 1950s aircraft. The main flaw of the Javelin was a massively thick wing, something Gloster was quick – but not quick enough – to identify. Before the Javelin even entered service, in 1953, they had begun research on a thin wing design capable of Mach 2.

In 1955 this design was seriously considered, partly as a contingency in case the Lightning didn’t deliver on its promise. The Air Ministry were initially skeptical of Gloster’s performance claims but when they eventually studied it in depth they were very impressed. Though the design would sacrifice some of the Javelin’s excellent range, in other areas it could produce an aircraft competitive with the latest US designs. The aircraft’s panned dimensions grew longer and more powerful engines were considered, and soon it shared little with the original Javelin. The concept was starting to show great promise, however when the UK’s Ministry of Supply were shown classified papers detailing the fantastic capabilities of the nascent CF-105 Arrow being developed in Canada, this warmed over design started to seem pedestrian. The supersonic Javelin seemed an expensive distraction that could only produce a mediocre design with limited development potential, and it was cancelled in 1956. A shame really, as if it had worked out it could have resulted in a versatile aircraft with better agility than the US F-4 Phantom II, itself a radical revamp of a disappointing design.

Full size thin wing Javelin mock up with Red Dean missiles.

5 Fairey Delta 3 ‘The Delta Belter’ (1956)

This Fairey Delta 2 experimental aircraft was the first aeroplane to exceed 1,000mph, and took the World Air Speed Record to 1,132 mph. It was a beautifully simple design with the delta wing’s inherent advantages of low supersonic drag and great structural strength. A year earlier the Air Ministry had issued requirement Specification F155T for a supersonic interceptor able to intercept Mach 1.3 bombers at 60,000ft. After initially proposing a modestly updated weaponised FD2, Fairey came forward with the mighty Fairey 3 — a vast super high-performance interceptor with state-of-the-art technology -—and won the contest.

Top 10 cancelled spyplanes here

Mixed propulsion (jet and rocket) was necessary to meet the extremely demanding requirement which called for the fighter to reach 60,000 feet at a range of 70 nautical miles from base in six minutes at a speed of at least Mach 2. The maximum climb rate would been phenomenal, leaving even the Lightning for dust — and even rivalling today’s fastest climber, the Typhoon. The thrust levels were astonishing – according to some sources it was to have two Rolls-Royce RB-122 engines— each of which which had a dry thrust of 19,500lbf, and 27,800lbf with reheat – greater than the present day ‘Flanker’*. And that’s not taking into account the additional rocket engines! Not bad for an aircraft that had normal operating weight of just over 50,000Ibs. Top speed was estimated at between Mach 2.3 and 2.5.

To soak up the heat generated by high speed supersonic flight much of the fuselage was to be built from steel (a material used on the Bristol 188 and MiG-25 for the same reason). It was to be armed with two of the giant Red Dean missile, which despite being thirty years before AMRAAM and even ten before the AIM-54, was planned as an active radar-guided missile.

Top 10 cancelled Soviet fighter here

Heavy ultra high performance heavy interceptors did not prove popular in the West. The XF-108 Rapier, CF-105 Arrow, YF-12 and Mirage 4000 were all cancelled; they were too expensive and air forces instead opted for more modest interceptors backed up by surface-to-air missiles. The Fairey 3 may have suffered the same fate had it survived Duncan Sandys ill-conceived crusade against manned aircraft of 1957, which it did not.

Fairey’s later F.155T proposal dwarfed its original, the E.R. 103 entrant (though this silhouette seems to share more with the FD2). One spin-off from the aborted E.R.103 was the AI23 radar which saw actual service on the English Electric Lightning.

*These thrust figures admittedly stretch credulity, so please let us know in the comments section if you have better info from a good citable source.

4. Hawker P1103/P1121 ‘Super Hunter’

Supermarine was not the only aircraft manufacturer that tried to adapt a transonic design into a supersonic fighter. Hawker tried the same with their own, already highly successful fighter, the Hunter. This was also offered in response to Operational Requirement F.155.

The limitations of the Hunter were already apparent, in particular the lack of air-to-air missile capability, decent radar and the ability to reach supersonic speeds. The new fighter interceptor would include a completely redesigned fuselage and wing (changing more profoundly than Trigger’s Broom), a seat for the radar operator, a far more powerful engine and missile armament. To make room for the new radar, a chin intake was adopted.

10 exotic cancelled fighter planes from countries you didn’t expect here

As with the Vickers 559, the original design included booster rockets for added climb speed, though in practice operational versions would have likely omitted them.

Over 99.7% of our readers ignore our funding appeals. This site depends on your support. If you’ve enjoyed an article donate here. Recommended donation amount £12. Keep this site going.

The P1103 was quickly knocked out the contest. One reason for this being the Ministry’s contention that Hawker had not embraced, nor even fully understood, the idea of the aircraft as a ‘weapon system’. But Hawker had faith in the design, and continued it as the self financed P1121. Power was to come from a single de Havilland Gyron jet engine*, and it was to be armed with Red Top missiles, rockets and Aden 30-mm cannon. Maximum speed was estimated at an astonishing Mach 1.35 at sea level — and a rather more believable Mach 2.35 at higher altitudes. The Air Staff still didn’t want it and reluctantly reconsidered the design before again turning their noses up at. The 1957 Defence White Paper put further nails in its coffin, though Hawker persisted with the idea for another year before giving up.

Ten incredible cancelled military aircraft here

The design would likely have inherited some of the fine handling characteristics Hawker had instilled in earlier aircraft such as the Hunter and Fury. The somewhat generous wing area and decent thrust-to-weight ratio (for the time) meant the ‘Super Hunter’ should have enjoyed good turn rates for its generation. A well balanced sensible design with impressive performance, the P.1121 could have enjoyed good export sales and offered the RAF a more versatile and combat effective fighter than the Lightning, and one that could have performed with excellence in both the air superiority and ground attack role.

*Jim Smith has noted, in conversation with Hush-Kit, Hawker’s predilection for single-engined fighters.

Despite looking somewhat like an F-16, this aircraft would have been more in the Su-9/11 and F-101 Voodoo class.

3. Martin-Baker MB.3/MB.5 ‘Martin Baker Tie Fighter’

I’m cheating a bit here, including two separate designs as one entry but Martin-Baker’s final two fighters were inextricably linked, one being a development of the other, both were outstanding and neither made it to production. Martin-Baker was (and indeed still is) an aviation component manufacture who produced, seemingly out of the blue, two of the best fighter aircraft ever flown anywhere.

Despite the crash it was apparent that the MB.3 was worthy of further development. Baker proposed a Rolls-Royce Griffon powered version, the MB.4 but a more thorough redesign was favoured by the Air Ministry and the MB.5 was the result. The best British piston-engined fighter ever flown, the MB.5 was well-armed (though with the less impressive total of four rather than six cannon), very fast, and as easy to maintain as its predecessor. Flight trials proved it be truly exceptional, with a top speed of 460mph, brisk acceleration and docile handling. Its cockpit layout set a gold standard that Boscombe Down recommended should be followed by all piston-engined fighters.

The only thing the MB.5 lacked was good timing, it first flew two weeks before the Allied Invasion of Normandy. Appearing at the birth of the jet age, with readily available Spitfires and Tempests being produced in quantity, both of which were themselves excellent fighters, there was never a particularly compelling case for producing the slightly better MB.5. There is also a suggestion that the MB.5 never received a production order because on the occasion it was being demonstrated to assorted dignitaries, including Winston Churchill, the engine failed. If this is true, it must rank as the most pathetic reason for non-procurement of an outstanding aircraft in aviation history.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Inexplicable official indifference,

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already,

Bad timing

2. Miles M.20 ‘The damned Captain Sensible’ (1940)

The M.20 was a thoroughly sensible design, cleverly engineered to be easy to produce with minimal delay at its nation’s time of greatest need, whilst still capable of excellent performance. As it turned out its nation’s need never turned out to be quite great enough for the M.20 to go into production. First flying a mere 65 days after being commissioned by the Air Ministry, the M.20’s structure was of wood throughout to minimise its use of potentially scarce aluminium and the whole nose, airscrew and Merlin engine were already being produced as an all-in-one ‘power egg’ unit for the Bristol Beaufighter II. To maintain simplicity the M.20 dispensed with a hydraulic system and as a result the landing gear was not retractable. The weight saved as a consequence allowed for a large internal fuel capacity and the unusually heavy armament of 12 machine guns with twice as much ammunition as either Hurricane or Spitfire. Tests revealed that the M.20 was slower than the Spitfire but faster than the Hurricane and its operating range was roughly double that of either. It also sported the first clear view bubble canopy to be fitted to a military aircraft.

Because it was viewed as a ‘panic’ fighter, an emergency back-up if Hurricanes or Spitfires could not be produced in sufficient numbers, production of the M.20 was deemed unnecessary since no serious shortage occurred of either. However, given that much of the development of the Spitfire immediately after the Battle of Britain was concerned with extending its short range, as the RAF went onto the offensive over Europe, the cancellation of a quickly available, long-ranged fighter with decent performance looks like a serious error. Exactly the same thing happened with the Boulton Paul P.94, which was essentially a Defiant without the turret, offering performance in the Spitfire class but with heavier armament and a considerably longer range. The only difference being that this aircraft was even more available than the M.20 as it was a relatively simple modification to an aircraft already in production.

The M.20 popped up again in 1941 as a contender for a Fleet Air Arm catapult fighter requirement, where its relative simplicity would have been valuable. Unfortunately for Miles, there were literally thousands of obsolete Hawker Hurricanes around by this time and with suitable modifications they did the job perfectly well.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Inexplicable official indifference,

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already

The dream of a supersonic STOVL (Short Take-Off and Vertical Landing) fighter has been striven toward for over half of the history of heavier-than-air flight. When the F-35B reached real operational readiness with the USMC, it was a very significant event. Lockheed Martin succeeded where dozens of the world’s greatest aircraft design houses have failed. The tortuous road which led, via the Harrier, to the F-35B started with NATO requirement NBMR-3 of 1961. This almost led to a British superfighter, the Hawker P.1154.

The author of Catch-22, Joseph Heller, fought with the 340th Bomb Group in Italy as a bombardier on B-25s. His commander was one Colonel Willis Chapman. Following the war, Chapman set up USAF’s first jet bomber force. In 1956, Chapman was sent to Paris as part of the Pentagon’s Mutual Weapons Development Plan (MWDP) field office. His mission was to source and help develop new military technologies from European sources and strengthen Europe’s contribution to NATO.

By the mid-1950s it was obvious to many western military planners that, in the event of war, Warsaw Pact forces would quickly obliterate NATO airbases. For NATO aircraft to mount counter- attacks (some with tactical nuclear weapons), they would need to operate from rough unprepared airstrips. This capability could turn air arms into survivable ‘guerrilla’ forces able to fight on after the apocalypse. VTOL was also tempting to many navies as it could eliminate the traditional hazards of carrier landing. If an aircraft could ‘stop’ before it landed, the task of landing on a tiny, pitching deck would be far easier. Likewise, it could liberate ships from the need to carry enormously heavy catapult launch systems, and could even allow small ships to carry their own, high performance, escort aircraft.

Here he encountered an idea from a French engineer Michael Wibault – steering jet thrust through steerable pipes to enable vertical take-off and landing. Chapman was very impressed and brought the idea to the attention of Dr. Stanley Hooker, director of the British Bristol Aero Engine Company. At this time Bristol were at the forefront of jet technology.

Hooker was also impressed. The VTOL research aircraft then flying used a series of batty principles which either involved rotating the whole fuselage (the tail-sitters), the engine of the aircraft (sometimes with the whole wing) or carried a battery of auxiliary lift-jets which once in flight were dead weight. All were complex and involved very large design compromises. Contrary to this, Wibault’s principle was simplicity itself; it involved a single fixed-engine, and would allow for the precise control of the vectored thrust.

Hooker led a team to develop the BE.53, a vectored thrust engine based on the first two- stages of the Olympus engine. Hooker teamed up with the designer of the Hawker Hurricane, Sydney Camm, to develop a light fighter concept powered by the BE.53.

At the 1957 Farnborough air show Hooker and Camm met Chapman. They showed him the design for P.1127. By early 1958 the MWDP were funding the BE.53 engine. The P.1127 fighter was struggling to get funding, as Britain’s Ministry of Defence believed that there would be no future manned bombers or fighters. This belief was expressed in the 1957 White Paper on Defence (Cmnd. 124) by Duncan Sandys — the most hated document in British aviation history.

Duncan Sandys had been Chairman of a War Cabinet Committee for defence against German flying bombs and rockets during World War II, and during this tenure he had accidentally revealed information about where the V1s and V2s were landing. This was a shocking error, allowing the Germans to accurately calibrate their weapons trajectories and endangering British lives. It also threatened to uncover Agent Zig-Zag, the famed double-agent, who at the time was feeding German intelligence false reports of bomb damage in London. His wartime experiences may have informed his belief in the late 1950s that missiles could take over from manned aircraft.

His 1957 report was also ill-judged, as 58 years later the UK received a new manned fighter (the F-35B) which is expected to remain in service for the next forty years.

As there was little official support in the UK, Hawker decided to fund the building of two prototypes itself, with some research support from NASA (who noted that, unlike rival VTOL aircraft, the P.1127 would not need a complex auto-stabilisation system). By the time Hawker had started building the prototypes, the MoD was interested and funded four more. The P.1127 first flew on 19 November 1960 and proved very successful. It could take-off and land vertically with ease, something dozens of research aircraft around the world had failed to do. But, it shared a deficiency with its rivals; an aircraft with a high enough thrust-to-weight ratio to lift vertically could carry little in the way of fuel or payload. This is where the P.1127 really came into its own. It was discovered that by putting the exhaust nozzle into an interim position (45 degrees) the aircraft could take-off in very short distances at very low speeds (60 knots, around half the taking-off or ‘rotation’ speed of a Hawker Hunter). At this point VTOL gave way to V/STOL (Vertical/Short Take-Off and Landing).

The MoD was now warming to the idea of a P.1127-based type and the RAF prepared a draft requirement (OR345) for a new V/STOL fighter of modest capabilities.

In 1961 NATO Basic Military Requirement 3 (NBMR-3) was issued. This followed on from the 1953 NBMR-1 (for a light weight tactical strike fighter, which was won by the Fiat G.91 and the Breguet Taon – though the Taon never entered service). The NBMR-2 was for a maritime patrol aircraft, and was won by the Breguet Br.1150 Atlantic.

NBMR-3 specification called for a single-seat tactical close-support and reconnaissance V/STOL fighter. The requirement demanded a combat radius of 250 nautical miles at a minimum sea level speed of Mach 0.92, and 500 ft altitude, while carrying a 2,000 lb store. This was a doomsday fighter-bomber, able to launch a retaliatory tactical nuclear strike from whatever improvised airstrips were available – even including selected motorway sections, heavily cratered main runways or worse.

The prospect of providing NATO with a common fighter soon attracted most major Western aircraft companies. NBMR-3 became the biggest international design competition ever held. Two months later NBMR-3 was split into two; AC 169a would cover a F-104G replacement, and kept the original demands: AC 169b was to be a Fiat G.91 replacement. AC 169b differed to AC 169a in calling for a lower payload-range requirement of 180 nautical mile range with 1,000 lb store.

Enter P.1154

At this point OR345 was dropped in favour of NBMR-3. Hawker Siddeley’s bid was the monstrous P.1154 powered by the insanely powerful Bristol Siddeley BS.100 engine.

The BS.100 was designed to produce a mighty 33,000 lb of thrust in reheat, around twice the power of the most powerful fighter engine then in service. The only engine with more power at the time was the Pratt & Whitney J58, which had yet to fly. The J58 was being developed for the top-secret Lockheed A-12 spy plane, which evolved into the SR-71 Blackbird. However, unlike the BS.100, at the speeds the J58 produced its maximum thrust, it was effectively a ramjet. As another example of how powerful the BS.100 was, the first fighter engine with greater power did not enter service until 2005 (44 years later). The engine was the Pratt & Whitney F119 and the aircraft was the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor. The BS.100 also introduced a bold new technology, Plenum chamber burning. Whereas a traditional afterburner pumps and ignites fuel where the cold bypass air and hot jet core turbine airflow are blended, the PCB only acts in the turbofans cold bypass air.

The potent BS.100 would have given the P.1154 a Mach 1.7 top speed, an unprecedented thrust-to-weight ratio and a scorching rate-of-climb. The aircraft was to be far more than just a brutish hot-rod, it was to be equipped with some very advanced avionics. Ferranti would provide the P.1154 with a radar which was at least a generation ahead of any other. The radar would feature both air-to-air and terrain-following modes. This was a true multi-mode radar, planned at a time when the world’s best fighters were carrying crude air interception radars with tiny ranges. The P.1154 would also have one of the world’s first Head-Up Displays (HUD). The HUD is a piece of glass in front of the pilot with vital flight information projected onto it, which allows the pilot to keep his eyes up and looking ‘out’ and not to be distracted by looking down at instruments in the cockpit. The aircraft would also be fitted with another piece of innovative equipment, Inertial Navigation System (INS), a technology first seen in the V2 rockets that Sandys’ had accidentally aided!

But Hawker Siddeley was not the only company to be lured in by the big bucks promised by NBMR-3. Italy had been fucked over by NBMR-1. The contest had declared Fiat’s G.91 the winner, but nationalism got in the way. National governments which had been more than happy to support their own bids to the contest grew shy when Italy won the contest, and the G.91 did not receive orders on the scale that could have been expected.

This time Fiat entered the handsome G.95. France, Germany, and even the Netherlands, submitted designs. The Netherlands’ Fokker D.24 Alliance, to be produced with help from US’ company Republic, was also powered by the BS.100. The very ambitious D.24 was also variable sweep (swing-wing).

Hawker and Bristol’s P.1154 was declared the winner, but history repeated itself. Though nobody was tied to buying the winners of NBMR contests, it still seems unfair that no country outside of Britain was forthcoming in wanting to invest in P.1154. Hawker had been stitched-up far worse than Fiat. Still, at least Hawker still had a generous MoD budget to work with, and the type was elected to replace RAF Hunters and RN Sea Vixens —what else could go wrong? Two things. The first was the differing needs of the Royal Navy and the RAF. The RAF wanted a single-engined, single-seater. The Navy wanted a two-seat, twin-engined aircraft. To some degree both the Navy’s wants may have been driven by safety regulations regarding nuclear-armed aircraft (though the single-seat Scimitar carried the Red Beard tactical nuclear bomb). The Royal Navy was also impressed by the McDonnell (later MD) F-4 Phantom II, and there were some within the Admiralty which considering this a safer option. Giving the P.1154 twin engines would involve a complex modification of the design. The BS.100 was too big, so Rolls-Royce Speys were selected. To stop a twin-engined P.1154 flipping over in the event of a single engine failure, a complicated twin-ducting concept was added (comparable to the V-22 Osprey’s transmission system). The Royal Navy also wanted a larger radar.

On top of this, P.1154 threatened the existence of the Navy’s big carriers, if these new machines could take-off in next to no distance, why did the navy need massive expensive carriers? It should be noted that the Navy intended to catapult-launch their P.1154s, using an US style of operation. The Navy’s self-preservation instinct was kicking in. While the RAF P.1154s could have been made to work (with limitations), many (even at Hawker) doubted the viability of the naval variant.

Technical problems

If the first major problem facing the P.1154 was inter-service differences, the second set were technical. The P.1154 would be firing hot, after-burning exhaust from its front nozzles down onto runways or carrier decks. The temperature was great enough to melt asphalt or distort steel- this was a big problem (the Yak-141 would later encounter similar problems). It would also churn up a potentially dangerous cloud of any present dirt.

Added to this was hot gas re-ingestion (HGR). The aircraft would be ‘breathing in’ its own hot exhausts on landing. This re-circulating hot air would raise the temperature in the engine to more than it liked, a very serious problem.

On 2 February 1965, the incoming Labour government, led by Harold Wilson, cancelled the P.1154 on cost grounds. Was this to be the end of V/STOL fighters? Well, fortunately not. While the P.1154 was being designed, Hawker had been busy developing the P.1127 into the Kestrel, with the help of funds from Britain, West Germany and the USA (initially from the US Army). This of course led to the Harrier, the famous jump-jet which today remains in service with the United States, Spain and Italy.

Hush-Kit would like to thank: Chris Sandham-Bailey from inkworm.com for his wonderful profiles, and Nick Stroud for providing access to his photographic archive.

Save the Hush-Kit blog. This site is in peril, we are far behind our funding targets. If you enjoy our articles and want to see more please do help. You can donate using the buttons on the top and bottom this screen. Recommended donation £12. Many thanks for your help, it’s people like you that keep us going.

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. Our site is absolutely free and we have no advertisements. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here.

Extract from Combustion and Heat Transfer in Gas Turbine Systems by E.R. Norster

What a marvelous summary! Having lived through this period I really appreciate all your work. My hat off to you for doing this.

Why bash the greatest PM since Churchill.

You’re mistaken – the article doesn’t mention John Major at all…

Edwina’s toy boy?

TSR-2 ?

Not a fighter.

Except Canada was one country thinking of buying it for that role (ironically to fill the void left when the CF-105 was scrapped). Beamont noted the handling was on-par with the Lightning (plus the acceleration was better)…so a TSR.2 fighter isn’t an outlandish idea.

TSR-2 was optimised for high speed, low level flight – hence wing design (small area, high wing loading) & terrain-following radar. Cannot imagine it being any good at altitude or in combat. Not designed for that job.

The jet on first picture looks interesting, I wonder what’s the name of it.

the American aviation industry and corrupt politicians were the British Aircraft industries most dangerous enemies…and Churchill was tolerated for 5 years..he was hated by the working man.for his views on unions and his remedies for the depression and great strike.They had to pay the dockside crane operators to lower the jibs he was so disliked.