Category: Top Tens

Top 12 fighter aircraft of 1949

If you were unlucky enough to still be flying a piston-engined fighter in 1949 you’d better hope your enemy didn’t have jets. The piston age was over. Though the ultimate piston-engined fighters were still serving they were now well out of their depth. The jet generation was just too fast to catch… but they were also very thirsty, short-ranged and extremely dangerous to fly.

1949 is an intriguing transitory period, many of the fighters you may have expected to be included hadn’t actually entered service yet, so no Tunnan, no F-94, no Venom, no Meteor F8, no CF-100, no Sea Hawk, no Saab 21R and, notably, nothing French. While the Arab–Israeli War (1948–1949) was little different to World War II in terms of the fighters types, with Spitfires and Bf 109 derivatives, a new age of aerial warfare was about to explode. The best of 1949 would not have to wait long for a baptism of fire in the unforgiving skies of Korea.

12. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-9 ‘Unwell Fargo‘

The I-300 had been the first Soviet pure jet to fly, a winning coin toss deciding its place in history in favour of the Yak-15 (which flew later on that same day in 1945). It was a horrible beast to fly, during a flight in 1946 it uncontrollably pitched down, crashed into the ground and killed its test pilot, A.N. Grinchik. He was replaced by the master test pilot Mark Gallai (a kind of Soviet Winkle Brown), who encountered the same pitch-down issue, which snapped one of the tailplanes off and ruptured the main fuel tank. Instead of bailing out, he made a remarkable, and successful, deadstick unpowered landing. Despite its many flaws, the I-300 was commissioned as a fighter, and assigned the designation MiG-9. The MiG-9 was predictably awful. One of its major issues was the engine flame-outs that occurred when the guns were fired at high altitudes. This was a major problem for a fighter. Its top speed of 537mph (slower than the I-300) was not great for a jet fighter, inferior to even the Me 262 clone Avia S-92. Still, it would have been fast enough able to run away from a Sea Fury. Its armament consisted of the hugely destructive Nudelman N-37 37-mm cannon and two Nudelman-Suranov NS-23 23-mm cannon. Though several advanced versions were tested, including one fitted with an afterburner capable of 600mph, they were not pursued. As soon as the superior MiG-15 was on the scene, it soaked up almost all resources available to develop fighter aircraft, starving lesser aircraft like the MiG-9.

11. Avia S-92 Turbína ‘Czech your privilege’

On liberation, Soviet forces seized all the German tools, jigs and components for Me 262 production they found in Czechoslovakia. These extremely useful scavenged parts were gifted to the new Czechoslovakian government. Avia had enough parts to build 19 aircraft. There is some debate as to whether this small force was active in 1949 (some sources say 1950). But it is interesting to note that four years after the War, what was essentially a Me 262A was still an effective fighter. With a top speed of 560mph it could decide when to fight, even against the most potent piston-engined fighters in service such as the Sea Fury, Twin Mustang, Bearcat and Sea Hornet. The inclusion of the S-92 above the finest piston-engined is debatable, it could be said to depend on whether you want greater speed performance with shitty BMW 003s which nobody would trust to keep running for very long or better range and utterly reliable engines. In general, it is probably fair to say a pilot would have been safer in peacetime in the final piston aircraft, and safer in a dogfight in one of the early jets, with his superior speed enabling him to dictate whether to engage. It is on these grounds that the questionable S-92 and lamentable MiG-9 are chosen over the wonderful final aircraft of a dying generation.

The S-92 had the advantage of a swept wing, still a relatively novel feature for fighter aircraft of 1949. Yugoslavia expressed an interest, but with the arrival on the scene of new Soviet designs, this did not happen.

10. Lockheed F-80C Shooting Star ‘Dove from above’

While the Bell P-59 was technically the US Army Air Force’s first jet fighter, the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star was the first to enter series production and see operational service. The prototype XP-80 first flew on 8 January 1944 and within eighteen months, the type was series production. The P-80A reached Squadron service by the end of 1945 and continued to fly alongside the newer P-80B for the next few years. The P-80As and Bs were both developed during wartime and funded through wartime contracts, but the next evolution, the P-80C (soon to be F-80C after June 1948) was the first Air Force type to reach production that was funded postwar.

Top fighters of 1945 here

By 1949, the F-80 had racked up an impressive history. With the blockade of Berlin in 1948, the 61st Fighter Squadron’s F-80Bs under 56th Fighter Group commander Col. Dave Schilling departed Selfridge Air Force Base on 12 July 1948 and headed across the Atlantic in order to protect the Allied aircraft of the Berlin Airlift. The mobilization, known as Fox Able One proved a fighter squadron could self-deploy overseas on short notice. When the squadron’s deployment ended in early summer 1949, Schilling led Fox Able Two, taking another squadron from the 56th across the Atlantic to replace them.

The 36th Fighter Group followed the 61st FS to Europe by 13 August 1948 and by the 20th were established at Furstenfeldbruck, Germany. The 36th spent the next eight months protecting Berlin Airlift aircraft from potential air threats from aggressive Russian pilots. But that was not the 36th’s only mission while at Furstenfeldbruck. During a training flight returning from Malta in 1949, members of the Group’s 22nd Fighter Squadron began practicing precision formation flying. Upon returning to Germany, those 22nd FS pilots began practicing standard formation aerobatics in the F-80B and the Skyblazers were born. The Skyblazers were actually the second USAF demonstration team, preceded by the stateside Acrojets a year prior. The Acrojets began flying F-80As but transitioned to the F-80C in 1949.

Top fighters of 1939 here

On the other side of the globe, Japan had become the Asian bulwark against Communist aggression, just as Germany had in Europe. The 8th, 49th and 51st Fighter Groups were all flying F-80B and C models from bases on Okinawa and the Japanese home islands. During the relatively calm days of 1949, the majority of Japan-based F-80s were arrayed against threats from newly Communist China, flying from Naha (51st) on Okinawa and Itazuke (8th) on the Japanese home islands. On the northern end of Honshu, the 49th flying from Misawa AB focused its attention northward, as the closest fighter unit to the Soviet Pacific Fleet homeport of Vladivostok.

The F-80 lineage diverged in 1949 with the first flight of the YF-94 Starfire on 16 April. The new all-weather interceptor was the first Air Force type fitted with an afterburner, giving the aircraft up to 6000lbs thrust. It also included a sophisticated fire control suite linked to a new air intercept radar controlled by the backseater. The weapons officer in the back seat would run the radar and direct the pilot to his target at night or in bad weather.

The F-80 of 1949 served in another distinct role as well. Fitted with a pair of K24 cameras in place of the machine gun armament, the FP-80 and after June 1948, the RF-80, provided critical tactical reconnaissance duties with the 363rd stateside and Japan with the 8th Reconnaissance Squadron. But due to peacetime budget constraints, the Air Force determined that reconnaissance squadrons were not critical infrastructure, and the 363rd Recon Group was deactivated in August 1949 after only two years of operation. One of the 363rd’s squadrons, the 161st was reassigned to the 20th Fighter Group at Shaw AFB, where it continued on as one of the only two reconnaissance squadrons in the air force.

In 1949, the Shooting Star still had somewhat of a technological edge, although that was rapidly fading as the F-84 and F-86 entered service. Improvements in the engine, weapons, and avionics allowed it to stay competitive as an air superiority fighter, despite the relative maturity of the design. The F-80 was not the fastest, nor the highest climbing, but it was good at what it did, both as an early interceptor and later as a fighter bomber. Later designs like the F-84 and F-86 built on the lessons learned by the F-80 programme even as they fought alongside the Shooting Star just a year later.

A 1948 fly-off assessment against the supposedly superior F-84C revealed that the older P-80 was more manoeuvrable, had a better low altitude climb rate and a shorter take-off run. It also was tough enough for rough field operation. The C model had greater firepower and more thrust than the B. With a top speed of 594mph, six fifty cal machine-guns and up to sixteen 127-mm unguided rockets it was not a fighter to be trifled with. But technology was moving so fast it would soon be easy meat for the MiG-15. Around half of the F-80C’s built would be lost to operational causes, 133 of the 277 lost would be destroyed by groundfire.

9. Yakovlev Yak-23 ‘Flora’

Highly manoeuvrable, with brisk acceleration and a good climb rate, the Yak-23 was a decent design doomed to obscurity by the appearance of far superior designs. It enjoyed a good thrust-to-weight ratio at normal operating weights of 0.46, superior even to that of the F-86 (0.42) thanks to its Soviet-built Rolls-Royce Derwent V engine. Its small size and great manoeuvrability were hallmarks of designer Alexander Sergeyevich Yakovlev. He had pushed for a lightweight and small design against official recommendations (the Yakovlev bureau’s larger Yak-25 fighter had been cancelled, proving markedly inferior to the rival La-15 and MiG-15, and dangerously prone to buffeting). The Yak-23 was fast, a top speed of 575mph at sea level was good for 1949, and the ‘Flora’ – with its twin 23-mm cannon – would have proved a handful for almost any opponent.

It would later snatch a world climb record.

8. Republic F-84D Thunderjet ‘Thunderjets are gauche’

By 1949, it was clear that Republic’s F-84 Thunderjet had failed to meet initial expectations. There had been hopes that the new Thunderjet would be a worthy successor to the mighty P-47 Thunderbolt – such that a contract for 25 YP-84As for evaluation and a further 75 production P-84Bs was placed even before the first prototype made its maiden flight on February 28th, 1946. But the type’s rehabilitation as a tough, fast fighter-bomber, combat proven in Korea, lay some way in the future, and in 1949 the Thunderjet was still in the process of working through a succession of teething troubles! The F-84B became operational with 14th Fighter Group at Dow Field, Bangor, Maine in December 1947, but within weeks was subject to a range of restrictions and limitations due to control reversal, and wrinkling of the fuselage skin. The F-84B was grounded on May 24th, 1948 after further serious structural problems were uncovered. The F-84C was powered by the much improved J35-A-13 engine, and featured fuel, electrical and hydraulic systems refinements, but both of these early models were judged unsuitable for their assigned role – neither being considered operational nor capable of executing any aspect of their intended mission. The J35 engines of the F-84B and F-84C had a 40 hour time between overhauls, preventing their use in Korea. The Thunderjet’s reputation was saved from ignominy by the service entry of the structurally improved F-84D in 1949. The F-84D’s wings had thicker aluminium skin, and the wingtip fuel tanks gained small triangular fins to relieve their tendency to cause excessive wing twisting (leading to structural failure) during high g manoeuvres. The further improved F-84E also entered service in 1949, with further reinforcement of the wings, a 12 in extension to the fuselage in front of the wings and a 3 in plug aft of the wings. The new variant had a roomier cockpit and enlarged avionics bay, and could carry an additional pair of 230 gallon fuel tanks underwing, extending the combat radius from 850 to 1,000 miles. Serviceability remained obstinately poor, however, and it would be another two years before the definitive plank-winged ’84, the F-84G, entered service. The Thunderjet did form the basis of the much better swept-wing F-84F Thunderstreak and RF-84F Thunderflash, but that is another story altogether

– Jon Lake, author of dozens of books about military aircraft

Top fighters of 1946 here

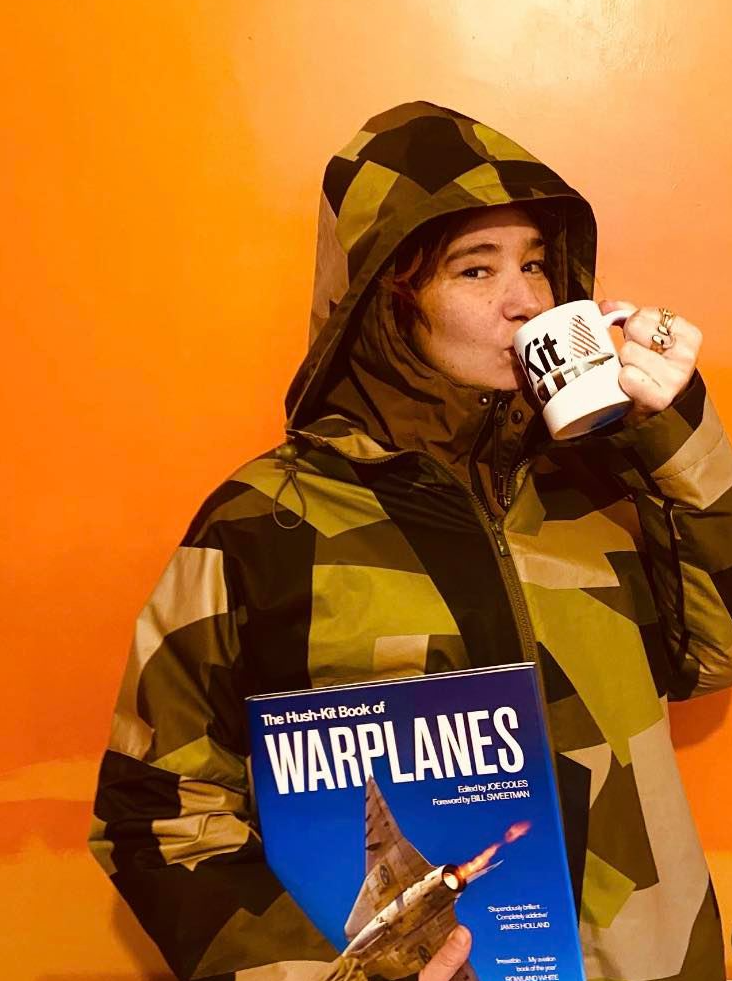

The extraordinary beautiful Hush-Kit Book of Volume 2 will begin when funding reaches 100%. To support it simply pre-order your copy here. Save the Hush-Kit blog. Our site is absolutely free and we want to keep it that way. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Treat yourself to something from our shop here. Thank you.

The F-84B and Cs had been a huge disappointment and it was only the promised improvements of the D variant that saved the type from the axe. The D entered service in 1949 with the improved J35-A-13 engine, and with a wealth of enhancements including greatly improved fuel, hydraulic and electrical systems. The Thunderjet was now pretty hot stuff. It could carry a greater bombload than the P-80, and was faster, with better high altitude performance and a greater range. With a top speed of 587 mph at 4,000 ft it was no slouch.

7. Gloster Meteor F. Mk 4 ‘Mr Mature’

With the definitive F.Mk 8 yet to enter service, the F.Mk 4 was the hottest Meteor in 1949. It was massively more powerful thanks to its two Derwent V (essentially a scaled-down Nene sharing little with the Derwent IV) engines each pumping out an additional 50% greater thrust than the earlier Derwent IV nengines of the later F.Mk 3s. In fact, it was so powerful it needed its wings strengthened to keep up with the extra speed. A new stronger clipped wing was introduced, which increased possible roll rates by 80 degrees a second and made the carriage of 2,000Ib of munitions on the wings possible. The F.Mk 4 was a full 80mph faster than the 3. A slightly modified* version of the F.Mk IV** snatched the world speed record in 1945 at over 606mph, a huge jump from the previous official record of 1939 469mph figure by the Messerschmitt Me 209 V1 (though several aircraft had gone faster since notably the Me 163 and 262, none had been officially recorded). With a top speed of 590mph, four 20-mm cannon in the nose and a ceiling of over 44,000 feet the Meteor F.Mk 4 was a machine to be respected, only let down by a thick unswept wing that limited its top speed. Despite first flying in 1945, the F.Mk 4 was not rushed into service. Britain had lost her lead.

*VHF mast and armament removed, high-speed finish applied to both aircraft. Painted yellow for the benefit of speed cameras **the RAF abandoned its rather pretentious and inconvenient use of Roman numbers for aircraft marks in June 1948)

6. McDonnell F2H Banshee ‘The Screaming Reborn Phantom’

During its first test flight, the nascent Banshee famously demonstrated a climb rate twice that of the F8F Bearcat, then the US Navy’s hottest interceptor. In August 1949 it set a US Navy jet fighter altitude record of 52,000 ft (16,000 m). Carrier jets were in their infancy; the first US example FH-1 Phantom had only made its first carrier landing three years earlier. The Banshee was a vastly improved and far larger fighter based on the Phantom. The Phantom had been the first jet aircraft concieved from the outset for shipboard operation, and was a case of an over zealous embrace of an immature technology – or to be kinder, a vital stepping stone. For a minute advantage in top speed over the best piston-engined rivals (it was a piffling 4mp faster than the British Hornet) it offered far greater peril and worse handling. Though it would mature into capable machine, in 1949 the Banshee was still suffering teething problems. In Wings of the Navy, the greatest British test pilot Eric Brown rated the Banshee F2H-2 as inferior to the Meteor IV. The large Banshee rectified most of the Phantom’s shortcomings and at 580mph had decent top speed, but in 1949 it was not the capable machine it would later become.

5. de Havilland Vampire FB.5 ‘Bantamweight bloodsucker’

Image: BAE Systems. DH100 Vampire FB.5 (VV217) air-to-air on 8th March 1949

Shortly after World War 2, the RAF decided to embrace the Meteor as its standard day fighter. This left de Havilland at something of a loose end until they decided to promote the Vampire’s potential as a ground attack aircraft. Having convinced the authorities this would be a good idea a few changes had to be made to accommodate the change in operating altitude. The wings were strengthened with extra stringers and thicker skins. They also had wiring for rocket rails and bomb racks fitted to augment the four 20-mm cannon. Perhaps more drastically a foot was cut from each tip which improved low-altitude manoeuvrability and made the ride smoother. This arguably also made probably the world’s cutest jet fighter even cuter. As a nod to the ground attack role some armour was added around the engine, which was hopefully some comfort to the pilots given it was found to be impossible to fit an ejector seat in the snug cockpit. At least not if he wanted to keep his arms. In 1947 the new model was designated the Vampire FB5, which gives an average of a Mark every 9 months since the Vampire’s first flight. Which is less time than it can take to get a warning label moved these days. By December of the following year No. 16 Squadron started to receive aircraft to become the first operational squadron. The FB5 of 1949 was a punchy ground attack aircraft that was still able to take on enemy fighters after delivering its payload. That could be up to two 500lb or 1000lb bombs and eight rockets, which compares well with what the Harrier was delivering during the Falklands Conflict. Although in the latter case the rockets were probably more accurate than the WW2 era 60lb models the Vampire used which, if the pilot was lucky, went in the general direction they were pointed without damaging the aircraft. With an endurance of around two hours or 1,000 nautical miles it didn’t suffer the small bladder issue of other early jets even if the pilots might. Its relative simplicity and ruggedness also made it capable of rapidly redeploying to a new base if required. Indeed, by late ’49 No. 6 Squadron were based at Deversoir in the Canal Zone while deploying to remote airfields around the Middle East. Although not quite as fast or exciting as some of the jets in service in 1949, and still featuring a wooden fuselage, the Vampire benefited from several years of development making it a more complete aircraft than any of its competitors.

Plus, did I mention how cute they were? Though tasked as fighter-bomber, the Vampire could eat the Meteor in a dogfight. Vampire pilots enjoyed excellent visibility out from the bubble canopy (except in rain), and were enamoured of the tiny fighter’s benign handling characteristics. With lighter ailerons than the Vampire F.3, the FB.5 had a sparkling roll rate at higher altitudes, probably better than any other aircraft on this list. Its rate of turn was also superb, as was its turn radius: the FB5 could turn in three-eighths of a mile (the Meteor needed a whole mile) at 5,000 feet altitude, which increased to one mile at 35,000 feet (again smashing the Meteor, which required 1.7 miles). In 1948 a Vampire reached the astonishing altitude of 59,430 ft, setting a world record. Not bad for a fighter type first flown in 1943. The FB.5 Vampire had a top speed of 548mph, outrageous agility and powerful armament in the form of four 20-mm short barrel Hispano cannon.

– Bing Chandler/Joe Coles

4. Grumman F9F-2 Panther ‘Panther Burns’

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/f9f-panther-large1-56a61c593df78cf7728b64df.jpeg)

Like the Army Air Force, the Navy’s experience with jet aircraft started during World War II. Due to Naval Aviation’s unique requirements, the Navy experimented with a few different types including composite airplanes like the Ryan FR-1 Fireball, which used both jet and piston engines. The McDonnell FH-1 Phantom became the Navy’s first pure jet powered airplane, first taking to the air in June 1945. But just two years later, it was deemed obsolete and relegated to a training role. That same year, the Grumman XF9F-1 took to the air for the first time. Grumman had provided the bulk of the Navy’s fighters during World War II and was eager to continue the tradition.

The new XF9F Panther had some initial teething problems but entered series production as the F9F-2 in 1948, with the first production models reaching the fleet in the Spring of 1949. VF-51 stood up in May and by summer the squadron was headed to the USS Boxer (CV-21) for carrier qualification. The squadron completed carrier quals by September and was declared operational.

The Panther was powered by a Pratt & Whitney J42 (manufacturer designation JT-6B), a license-built version of the British Rolls Royce Nene, that produced 5000lbs of non-afterburning thrust. The J42 gave the straight-wing Panther a top speed of 575mph, which was significantly slower than the Russian MiG-15 which was powered by roughly the same engine; a reverse engineered Nene designated the VK-1.

Unlike the Air Force’s F-80, which was originally designed as an interceptor and then evolved into an interceptor, the Panther had been built as a fighter bomber. It was armed with four AN/M3 20mm cannon with 190 rounds per gun and was capable of carrying 3,000lbs of bombs and rockets for close support and interdiction work. This capability was critical for the next squadron qualified in the type; the Marines’ VMF-115, who along with VMF-311 would take the type into combat alongside Navy squadrons the following year. F9F-2B BuNo 123526, on exhibit at the National Museum of the Marine Corps would lead the first Marine Corps jet combat mission in Korea on 10 December 1950.

While 1949 was a significant year for the Panther’s introduction to squadron service and the first mass production of a Navy jet fighter, another significant development that would improve the design also occurred that year. The F9F-5 first took to the air in December 1949 and offered significantly better low-speed handling characteristics, which greatly improved landing approaches. The newer model was lengthened by sixteen inches and housed the more powerful J48 engine, producing nearly 2000lbs more thrust than the J42. The F9F-5 would be the ultimate version of the straight-wing Panther, reaching squadron service by the end of 1950 and entering combat just over a year later. The Panther would go on to score the first jet-versus-jet kill.

– Jonathan Bernstein is an aviation author, historian, former attack helicopter pilot and Arms & Armor Curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. You can buy his book on P-47s here

The Panther was developed following the entirely unsatifactory study of a four-engined Grumman two-seat night fighter. The new design was small, tough and agile. Like the MiG-15 and some Vampire variants, the Panther was powered the British-designed Nene turbojet, licence produced in the US as the Pratt & Whitney J42. The F9F-4 model was delivered from late 1949 but did not enter operational service that year, it included the fuselage extension of the -5 without the powerplant upgrade. The -5 also made its first flight in ’49 but was in not service. It featured an Allison powerplant, the J33-A-16, which featured water injection to boost take-off thrust. In this time the Panther was more mature than the Banshee, and offered very similar capabilities (including the same armament) in a smaller airframe. Armed with four-cannon and ‘built like a Grumman’, it was tough sound design featuring the on-trend tip mounted fuel tanks (‘tiptanks’).

3. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15

In 1949 every preening fighter pilot* in the Soviet Union wanted to fly the MiG-15. A wonder in polished aluminium with a bright red star on the tail it could achieve the almost unbelievable speed of 669 mph at Sea Level thanks to secret German research from the mid-40s that led to it having a wing swept to 35 degrees. Compared to the straight-winged MiG-9 or the piston-powered Yak-9 this was clearly the future. While the West were still getting to grips with putting the Nene engine into the comparatively conservative Sea Hawk and the positively pedestrian Attacker the Soviet Union was forging ahead by putting their ‘equivalent’ RD-45 into the MiG. It’s almost as if letting Rolls-Royce sell the Soviet Union 25 Nene for ‘civil use only’ was a mistake. In fact, the Sea Hawk was still four years from entering service while the Soviet honchos were enjoying the benefits of ejection seats, the decadence of air conditioning, and a maximum speed of Mach 0.92 to the Sea Hawk’s 0.84.

All was not totally rosy in the final year of the ‘40s however. At this stage in its career the MiG was only to be flown on fine days, while aerobatics or combat manoeuvring were out of the question. There were also a few teething problems, for instance, if you went too fast the lack of quality control on the production line would lead to uncontrollable rolling which initially had to be fixed with manual trim tabs added to the ailerons. This probably wasn’t helped by the lack of hydraulic assistance on the early MiG-15’s flying controls. Still at least the air brakes were hydraulic. Even if they caused the aircraft to pitch up when they were deployed and didn’t really slow the aircraft down enough.

Assuming the pilot managed to overcome these issues with a combination of luck and skill there were also slight issues with the armament. Although the choice of two 23-mm and one 37mm-cannon provided plenty of punch, the differing ballistics of the two rounds could make aiming tricky with one set of rounds going above the target and the other below.

The good comrades at MiG were aware of these shortcomings and even as the first aircraft were being delivered to the VVS they were preparing to produce the MiG-15bis which would feature stiffer wings, servos for the controls and effective airbrakes along with a host of other minor modifications. This however wouldn’t enter service until 1950. In 1949 the MiG-15 looked like the future while being a terrifying thrill ride that could appear barely under the pilot’s control.

The MiG-15 could out-turn, out-accelerate and out-climb the early Sabre. It was an utterly formidable machine. Early variants of the F-86 could not outturn, but they could outdive the MiG-15. The early MiG-15 was superior to the early F-86 models in ceiling, acceleration, rate of climb, and zoom. It had better high-altitude performance than the Panther or the P-80, and was faster by a hundred miles per hour.

* Is there any other sort?

2. Lavochkin La-15 ‘The unlucky Fantail’

The Lavochkin La-15 had superior manoeuvrability to the MiG-15, and with a top speed of 626 mph (some sources say 638 mph) was almost as fast. It had excellent handling chracteristics and was superbly reliable. It entered service in the VVS Autumn of 1949. It was smaller and lighter than the MiG-15 and did enjoy the stellar climb rate, though still climbed very well for the time.

It was powered by the RD-500, essentially a Soviet-built British Derwent, and armed with two 23-mm NS-23 cannon. It was rather harder to produce than the MiG-15, relying on many milled parts, and this was a major factor in the Lavochkin’s relative lack of success – only 235 aircraft were produced. It remained in service until 1954. It was the beginning of the end for the Lavochkin design bureau fighter line that had been so vital to the Soviet Union’s war effort. Lavochkin La-200 flew in 1949 but failed to secure orders, as did the later La-250. Lavochkin was reborn as a creator of surface-to-air-missiles and spacecraft. Today, the company is working on the appallingly named Mars-Grunt space robot.

- North American F-86A Sabre ‘Jet spitfire’

An astonishing top speed of 679 mph at Sea Level and excellence in every category a fighter needs, North American Aviation did the almost impossible and built an aircraft even more outstanding for its generation than its P-51 Mustang, which first flew a mere seven years before the F-86.

The Sabre started life as a straight wing jet based on the even more staid FJ-1 Fury of the US Navy. By making it lighter North American Aviation managed to, just about, match the performance of the other aircraft submitted to the USAAF (which would become the USAF three weeks before the sound barrier was broken in 1947). Realising radical steps needed to be taken to come up with a winning design, they took the only logical step and like the Soviets used secret German research from the mid-40s. This led to the incorporation of a thinner wing swept to 35 degrees giving the resultant design the ability to go supersonic in a dive. So successful were these changes that if you’re the kind of person who likes winding people up and invoking the wraith of the Yeager crowd up you can argue the XP-86A and George Welch were first to break the sound barrier.

Interview with Sabre pilot here

The F-86A entered frontline service in February of 1949 with the 94th Fighter Squadron who also seem to have been instrumental in giving it the name ‘Sabre’. Despite barely being out of trials the Sabre was already a delight to fly. Unlike the MiG-15 it had hydraulic boost for the flying controls, was well enough put together to remain controllable as it approached and passed the sound barrier, and air brakes that were effective. Leading-edge slats also made it much safer to fly at low speeds. Together with the all-round visibility provided by the Sabre’s bubble canopy these factors would give it the edge against the MiG in combat even allowing for the latter’s better thrust-to-weight ratio.

The F-86A wasn’t quite perfect, unlike the E model introduced in 1951 it lacked a ‘flying tail’ arrangement where the entire tail surface acts as the elevator. Instead, it had conventional elevators while the tailplane’s incidence could be adjusted via the trim system. As aircraft approach the speed of sound air over the wing surfaces accelerates to above Mach one, this causes shock waves to form at the hinge lines of control surfaces. These shock waves blank the control causing it to be less effective. In the A model Sabre above Mach 0.97 this meant pitch control was almost entirely reliant on the trim. Indeed, if the elevator alone was used to pull out of a supersonic dive there were generally less rivets in it on landing. Still, this was a minor blemish on an otherwise excellent aircraft.

If the MiG-15 was a diamond in the rough in 1949, the Sabre was the finished product noted test pilot Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown even going as far as praising the ground handling and nose wheel steering system. – Bing Chandler

If you enjoyed this free article support The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 2 by pre-ordering your copy here. (link goes to volume 2 but you can find volume 1 on the same site)

Top 12 Swedish aircraft

Swedish aircraft are a breath of fresh air. Idiosyncratic, clever and unorthodox, they have often been the result of a different way of thinking and peculiarly Swedish needs. That such a small nation makes its own combat aircraft is a quirk of history. Sweden’s non-aligned neutrality policy, which lasted until 2009, had its roots in the calamities suffered during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century. The disastrous results included a loss of over a third of Sweden’s territory, most notably Finland, were not soon to be forgotten. A policy of avoiding military intervention and international allegiances wherever possible began in the early 19th century. In the 1930s, fearing a second world war, Sweden massively increased its defence spending. The War showed that neutrality was not always easy or carried out to the letter. In World War II, Sweden made itself very unpopular with the allies by supplying large amounts of vital iron ore to Nazi Germany, though Sweden was also exporting significant quantities of ball bearings to the Allies. There were trade agreements between Sweden and the Allies for these purposes, and during the latter parts of the War this included limiting Swedish exports to Germany (once Germany was too weak to pose a significant threat to Sweden anymore). Such is the delicate complicated position of non-alignment. This policy of ‘armed neutrality’ required indigenous armaments to avoid dependence or allegiance to a foreign power. From the mid-1940s Sweden’s Försvarets forskningsanstalt (FOA) intended to develop it own nuclear deterrent, an ambition it chose to give up when it joined the non-proliferation treaty in 1968.

It was the smallest nation, in terms of both population and economy, to design and build its own advanced military aircraft. But there are shades of ‘indigenous’ as no country other than the US and Russia (and lately China) has access to the full spectrum of technologies required to make a modern fighter. The Gripen, for example, uses a British ejection seat, an (essentially) American engine, pan-European air-to-air missiles and a German gun. The reliance on US tech has enabled the US to block export licences in order to scupper several potential Saab exports that threatened US sales, most notably Indian interest in the Viggen in the 1980s.

Let’s head North to the icy beauty of Sweden to choose twelve incredible Swedish aeroplanes.

12. Saab 21 (1943)

There are reasons that propellers are at the front, and most of them relate to that being the way engines are designed to turn them. The perils of the pusher are such that the US Army banned pusher designs in 1914. Shame though, as a pusher means you can have your guns very easily placed on the centreline, a shorter fuselage and a greatly improved view for the pilot.

The Saab 21 did not have a spectacular performance; 400 mph may have been insanely fast in 1940, but by 1945 when the J 21 entered service it was decidedly mediocre. To avoid a diced pilot, an ejection seat was required, the J 21 being the first non-German aircraft to carry an ejection seat as standard. The aircraft was well-armed, with one 20-mm cannon and two 13.2mm heavy machine guns in the nose and two more heavy machine-guns in the wings.

Powered by the Daimler-Benz DB 605 that had powered the cream of axis inline fighters, the J 21 was hampered by the war ending and the 605 line ending. Intriguingly, there were plans for a more advanced version with a Rolls-Royce Griffon and a Mustang-style bubble canopy, these never happened as the jet age had arrived. The J 21 become part of one of the very rarest aircraft breeds, those that went from piston to jet propulsion as the J 21R.

11. Saab B 17

No, not that one. The B 17 was Saab’s first aircraft and Sweden’s first indigenous ‘modern’ stressed-skin monoplane. Unusually conventional by Saab standards, the aircraft had already been designed by ASJA, the catchily named AB Svenska Järnvägsverkstädernas Aeroplanavdelning (Swedish Railway Workshops’ Aeroplane Department) thus joining the likes of the Henschel 129 and the English Electric Lightning in the surprisingly crowded pantheon of aircraft built by railway locomotive manufacturers. The B 17 was a workmanlike design that compared well with contemporary single-engine light bombing aircraft. And if you think it looks particularly similar to US designs of the era, the fact that between 40 and 50 American engineers were employed by ASJA on its development might not come as a total surprise. Intended for the dive-bombing role, the B 17’s wing wasn’t up to the strain of this form of attack and required strengthening. Although subsequently cleared for diving attacks, the B 17 was limited to a shallow angle of dive for the rest of its career. Speed in the dive was limited by the large undercarriage doors which functioned as dive brakes when the B 17 made its attack and on the subject of undercarriage, the wheels of the undercarriage could be switched for retractable skis for winter operation. To add even more variety 38 examples of a reconnaissance floatplane version was also built.

Entering service in 1942 over 300 were built, most of the B 17 bomber version, with just over 20 of the S 17 reconnaissance aircraft also constructed. The Saabs remained in frontline service until 1950 though continued in second line roles for a further time, latterly as a target tug into the early 1960s. A potentially exciting aside occurred during the war when 15 B 17s were loaned to exiled Danish forces in Sweden to support a Danish invasion intended to liberate that nation from German occupation, known as Danforce. Thankfully the war ended before Danforce were committed to retaking Denmark, the Danish markings on the Saabs were painted out and the aircraft returned to Swedish control. Around the time that the aircraft was being withdrawn from Swedish service, 47 were bought for use by the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force. Ethiopian Saab 17s would be the only examples to fire their guns in anger, at least once, when several were used to attack a group of Somali criminals who had derailed and robbed a train. The Saab 17 was operated by Ethiopia until 1968 and thus the last frontline examples of this Scandinavian aircraft saw out their careers under the African sky. Of five survivors, one example remains airworthy at the Swedish Air Force Museum at Linköping.

10. Saab JAS 39 Gripen (1988)

On 29 March 2011, the Swedish Air Force sent combat aircraft to war for the first time since 1963. Eight Saab Gripens supported by a Saab 340 AEW&C and a C-130 Hercules tanker were deployed in support of the No-Fly Zone over Libya. The small fighter-bomber performed well. Initially, it was tasked purely with counter-air, but NATO planners noticed the Gripen had a very capable reconnaissance pod (the SPK 39) and its responsibilities were accordingly widened.

A rather boutique operation, the Saab Gripen has seen a small factory create around 280 aircraft since the type first flew in 1988. It has served in unobtrusive numbers around the world for sensible air forces on a budget. It is considered by many to have the lowest cost per flight hour for a modern fighter, and is relatively easy to maintain. I spoke to a Gripen maintainer a few years ago and he complained of not having enough to do, he had come from a MiG background. It is comparable with a top of the range small car, coming with a wealth of high-end accessories which include one of the world’s best helmet display and cueing systems, the formidable IRIS-T infra-red missile and the well trusted ‘404 engine. Perhaps the most impressive ‘accessory’ is the long-range Meteor air-to-air missile, giving a bantamweight the reach of the heaviest heavyweight. Much of the Gripen’s magic comes from a wealth of invisible capabilities: its electronic warfare suite is extremely well-respected by pilots who have ‘fought’ against the Gripen in international exercises. The basic philosophy of the Gripen was to create the smallest possible aircraft that wouldn’t be laughed out of a war with the Soviet Union. According to Tony Inesson, “Swedish defense planning also more or less assumed a NATO intervention. The Soviets never really considered Sweden a truly neutral power, but rather as being aligned with the West.” Building an air force that could take the USSR on its own terms was impossible, but one that could slow an invasion down until NATO leapt into the fray was possible. In the 1970s when what became the Gripen was first being considered Sweden’s defence planners had a big think. The cost of new, ever more complex, combat aircraft was generally spiralling out of control, one exception to this was the US F-16 which was smaller and lighter than the aircraft it replaced. Saab studied the F-16 with interest and wondered whether something even smaller might be able to replace its Viggens. Advances in materials and electronics, as well as engine technology, aerodynamics and flight control systems, enabled the Gripen to emerge as a bantamweight fighter with a hell of a punch. The new fighter, which first flew in 1988, was 6,000-Ib lighter than the Viggen and in aerodynamic form showed the future path of European combat aircraft. It was the first of a new class of canard-deltas, and has since been joined by the European Rafale and Typhoon, and the Chinese J-10 and J-20.

The next-generation Gripen will be the E (and two-seat F.) These are larger heavier aircraft powered by the F414, they are set to enter service soon.

(Some have argued that the Gripen’s use in Libya was largely a PR exercise to promote the Gripen for export, but Fredrik Doeser has argued that this view does not hold water as it could have been deployed to Afghanistan and the aircraft was already favourably viewed, something that could have been changed by any teething issues in its first combat deployment)

9. Saab 340

Had the Habsburgs stuck around long enough to get into the aircraft-making business, their offering would’ve been something like the Saab 340. It’s reliable and innovative, sturdy, loved for its handling and cost-effectiveness, loathed for its noisiness and its less-than-luxurious accommodations, lacking space for all its baggage (in the overhead bins, anyway), pretty to look at until you start adding military bits and bobs to it, and managing to stick around long after conventional wisdom deems it out of fashion. Sometimes it hears its name mentioned in a not-so-friendly way (though not due to any fault of the aircraft itself), but, at the end of the day, as regional airliners go, you could do a hell of a lot worse. After all, you don’t enjoy a nigh four-decade lifespan, hear your number called for hauling passengers and freight on three-hour hops to remote Alaskan airstrips, and get adapted for the maritime surveillance role (Japan Coast Guard) and airborne command and control (Swedish and Royal Thai Air Forces) if you’re not doing something right. The Erieye Airborne Early Warning and Control System fitted to the 340 AEW (among other airframes) has an AESA radar as its primary sensor and is widely considered world-class.

The 340 has gotten a lot of undue flak on the Internet, mostly from travel bloggers who seem to have severe allergic reactions to anything vaguely resembling a propeller, which is unfortunate, as it’s proven to be an excellent aircraft throughout its career, replete with forward-thinking technology like diffusion welding instead of rivets and, with the Saab 340B Plus variant, a noise and vibration reduction system (which, alas, came too late to help the poor 340’s reputation for being loud). It’s carried presidents and popes, and plenty of happy passengers.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol II will be a fantastic sequel to The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1. As soon as it reaches 100% funding, work will begin and what an incredible book we have planned. Click on the image below to pre-order.

The extended version, the fifty-seat Saab 2000, had the misfortune of coming on scene just as airlines were transitioning over to regional jets, and only sixty-three were built. As for the 340, production capped at 459 airframes, and, while there’s a trend among the major air carriers moving away from aircraft in the 340’s capacity category (generally 34 to 37 seats), and the 340 is getting up there in years, the type can still be found with about forty airlines and air arms. Regional turboprops might lack the sex appeal of fast jets like Drakens or Viggens or Gripens—though I should reiterate that, military variants notwithstanding, the 340 is quite a cute little fellow—but the 340 has certainly done more than enough to earn a place on any list of Sweden’s finest flying machines.

The extraordinary beautiful Hush-Kit Book of Volume 2 will begin when funding reaches 100%. To support it simply pre-order your copy here. Save the Hush-Kit blog. Our site is absolutely free and we want to keep it that way. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Treat yourself to something from our shop here. Thank you.

8. Saab 37 Viggen

It is said that Sweden could either afford the Viggen or the bomb, but not both. Sweden chose the Viggen and gave up its nuclear ambitions. Clint Eastwood asked for the Viggen to star alongside himself in his wild 1982 Cold War espionage thriller Firefox. The aircraft would have played the futuristic MiG-31 ‘Firefox’. On looks alone, can you blame Eastwood? The Viggen looked like the future, and in many ways it was.

The first thing you notice is the configuration. Aside the kidney-shaped air intakes, ahead of the main wings are a small set of ‘wings’ known as canards. Canards had been fitted on the American XB-70 Valkyrie bomber, the Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-8 and a few other experimental types, but the Viggen was the first modern canard-equipped aircraft to enter service. Unlike later canard-deltas, these were not all-moving, but they were fixed with a moving trailing edge flap. Not only do they render the Viggen, arguably, a Mach 2-capable biplane but they do other, more tangible, things. The Viggen also has an unusual wing shape. Having two angles of leading-edge sweep-back (the ‘kink’ or ‘dog leg’) allows for greater amounts of more stable lift from a wing of less relative area. This happens because the change in leading-edge angle keeps lift-generating air vortices from originating at the wing root. The earlier Draken and (later mark) Vulcan also featured rather different kinky deltas. India’s Tejas fighter has opted for a similar wing design solution to the Viggen.

Short-take off and landing was a key requirement for the type. To stop the aircraft without the fuss and hazards of a brake chute, an impressive thrust reverser mechanism – unique on a combat aircraft at the time, was added. Consisting of three triangular steel plates, it was closed up to redirect engine thrust forward through the side slit below the tail. The pilot could actually reverse his machine on the ground without the aid of a ground vehicle. Most famously, and a Swedish air show perennial, the Viggen could do a fast touch-and-go manoeuvre in which it would come in hot, arrest itself on landing with reverse thrust and then via a so-called Y-turn change the direction it was facing and rip right back into the sky on afterburner. All in a few seconds! Try that in a General Dynamics F-111. The Viggen was expected to operate from 500 to 800 metre lengths of motorway or damaged bases and be readily looked after by reservists and conscript groundcrew. It had fairly tall tandem main landing gear with anti-lock brakes. The Viggen almost seemed to handle like a sports car on the ground.

That was far from the only innovation in the Viggen: at the heart of the Viggen’s system was the CK 37 central computer (Central Kalkylator 37), the world’s first airborne computer to use integrated circuits. Many nearly boutique-level design touches were incorporated all across this aircraft’s systems. The earlier Saab 35 Draken was intended for the same ground-controlled, high altitude missile interceptions of the Convair F-102/106 or the Sukhoi Su-15; the JA 37 fighter variant of the Viggen embodied a dark recognition that future armed conflict might be a little more dirty and tactical – and require greater intelligence.

The Viggen came in five flavours: the AJ37 attack version, SK37 two-seat trainer, SH- and SF37 reconnaissance variants and the final version, the JA37 fighter-interceptor.

The Viggen had an impressive early example of a centralized computer to support the pilot by integrating and partly automating tasks such as navigation and fire control. The Central Kalkylator 37 was connected to a head-up-display and an X-band radar set. This gear meant the Viggen could meet a requirement for single-pilot operation. Performance metrics would also have been impaired thanks to the weight and space requirements of accommodating a second crew member so the dependence on technology was vital. The Viggen is most often celebrated for its out-of-the-box structural engineering but its avionics package ultimately is what made it the right investment for the Flygvapnet into the 2000s.

The Viggen was so clever in so many ways.

Its vertical fin could be folded down with dispersal to hardened bunkers or caves in mind? The outdoorsy Swedish jet made some of its Soviet and Western contemporaries look like precious hangar queens dependent on massive budgets and large, vulnerable air bases. In the Viggen, Sweden was able to extend the achievements of the Draken program and impress the world. A high-intensity R&D programme – fully funded and supported by the Swedish government – and a national flair for industrial design, combined with the employment of U.S.-licensed engine brought forth a winner.

Stephen Caulfield

7. Saab B 18

With its funky pusher propeller fighters, crazy double deltas and early adoption of the canard for jet fighters, it is difficult to accuse Saab of being a slave to convention. Thus at first glance, their only twin piston-engine bomber, the B 18, looks disappointingly ordinary, sort of halfway between a Ju 88 and a Hampden. But this elegant twin rewards a closer look as its arguably humdrum appearance was somewhat deceptive. First off, the cockpit is offset to the left, and as anyone who has ever glanced at a Sea Vixen or a Canberra PR.9 knows, offset cockpits are cool. Secondly, despite looking rather outdated considering it entered service in 1944, its performance was distinctly impressive with a top speed only 20 km/h slower than the vaunted de Havilland Mosquito FB.VI despite carrying three Swedes rather than the mere two of the Mosquito, one of whom got to wield a defensive machine gun. The Mosquito similarities didn’t end there: limited numbers of both (18 Mosquitoes and 52 Saabs) were equipped with a large calibre gun for the anti-shipping role. Weirdly both aircraft went for a 57-mm weapon.

And both aircraft were effective multi-role platforms before multi-role was really a ‘thing’ and could carry a vast array of different weaponry. The Saab however was never developed into a night fighter, for that role the Swedish used the J 30: which was their designation for the Mosquito! Most surprising of all perhaps is the fact that this fairly normal-looking WWII medium bomber was fitted with ejection seats. Sadly this was due to the Saab 18 garnering something of a reputation for crashing by the late 1940s. Ah well, the dangerous planes are always the most exciting right? For a Swedish aircraft the Saab 18 also pushed the envelope when it came to Sweden’s famed neutrality. In the reconnaissance role, B 18s were utilised during 1945 and 46 to overfly Baltic ports and photograph all Soviet shipping they found. In the course of these missions the Saabs were routinely subject to interception attempts by Soviet fighters but their speed rendered them essentially invulnerable, notably unlike other aircraft operating as spyplanes – Sweden lost an ELINT C-47 to Soviet fighters in 1952, then the search and rescue Catalina they sent out to try and find the missing aircraft was shot down too three days later sparking a major diplomatic incident. The B 18 remained in service until the late ‘fifties with the reconnaissance variants the last to be retired in 1959, replaced by another cool-looking Saab product (of course), the Lansen.

6. Saab 29 Tunnan (1948)

Aren’t Tunnans Brilliant. It’s 1948 and Europe’s aircraft manufacturers are busily reading captured German documents to learn about swept wings. But while Hawker and Supermarine are messing around with attaching them to a couple of spare airframes for research purposes, SAAB are test flying Europe’s first non-fascist swept wing production fighter. By 1951 the J29 Tunnan is in squadron service while the RAF are enduring the more pedestrian looking de Havilland Venom. To add insult to injury the shiny Swede used the same Ghost engine as the Venom to go faster, claiming two FAI speed records for the 500km and 1000km closed circuits. It could also carry 700kg more, which makes you wonder what de Havilland were doing. By 1954 the J29 had even gained an afterburner, one of the first aircraft to do so. But beating the low hanging fruit of de Havilland’s difficult second jet fighter isn’t all the Tunnan has going for it. SAAB’s most produced aircraft with 662 built, it served until 1967 as a front-line fighter and was still in use as a target tug until 1976. It was also the only SAAB to date to see combat helping with peacekeeping efforts in the Congo under the control of the United Nations. This saw 9 J29Bs and two S29C photoreconnaissance aircraft adorned with UN markings, literally just a big U and N painted on the fuselage, and operated by F22 Wing of the Swedish Air Force. Despite taking ground fire on numerous occasions while carrying out strikes on secessionists and mercenaries no Tunnans were lost in combat. Ironically after surviving the civil war all but four were then destroyed at their base in 1963 as it wasn’t considered cost-effective taking them back to Sweden. Objectively good looking and a technological trail blazer*the Tunnan is a brilliantly packaged little fighter, just look at how the landing lights drop down from the nose and the main gear tucks into the fuselage. The J29 also fitted an ejector seat before they became de rigeur.

5. FFVS J 22 (1942)

By 1940, the fighter component of the Flygvapnet consisted mostly of the Gloster Gladiator (designated J 8 in Swedish service) which were looking increasingly old hat when compared to the latest monoplane fighters busily shooting each other down all over Europe. In an attempt to maintain a credible defensive force Sweden ordered large numbers of the Seversky P-35 and Vultee P-66 Vanguard from the US only for the Americans to slap an embargo on the export of all arms to any country except the UK after only 60 P-35s had been delivered. To be fair this may have been a blessing in disguise as the P-35 (J 9 in Sweden) was a pretty woeful fighter. Sweden looked around for a replacement and intriguingly considered the Mitsubishi A6M Zero amongst others (concern about the practicality of delivery put paid to that idea). Orders were ultimately placed for the outdated Fiat CR.42 (J 11) and Reggiane Re.2000 (J 20) but neither was considered entirely satisfactory and the decision was taken to manufacture a fighter domestically instead. Sweden’s only major aircraft company, Saab, had their hands full manufacturing the B 17 (not that one) and B 18 so, impressively the Swedish government created a firm and factory from scratch specifically to design and build a new fighter: the Kungliga Flygförvaltningens Flygverkstad i Stockholm (“Royal Air Administration Aircraft Factory in Stockholm”) shortened to FFVS. From the start the aircraft was intended to be relatively light and simple and to utilise the reliable Pratt and Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp which was also the engine of the Seversky P-35/J 9. Unfortunately Sweden had no means to procure any more R-1830 engines from the US due to the embargo and no spare engines had been delivered with the batch of Seversky fighters that had been delivered. Therefore the Swedes elected to copy the engine and start production domestically, no small undertaking in the absence of any plans or drawings. The unlicensed Twin Wasp copy, designated the STWC-3, eventually powered most of the J 22s but the engine programme ran slightly behind schedule and to make up the numbers 100 R-1830s managed to be procured from the Vichy french regime. The purposeful looking FFVS J 22 was conventional in layout, apart from the undercarriage which was unusually narrow for its height and retracted into the fuselage in a unique arrangement. The construction method used was novel with plywood sheets cladding a steel-tube frame, the plywood skin being partially load bearing. The J 22 flew for the first time in September 1942 and considering this was the first fighter aircraft designed in Sweden since the Svenska Aero Jaktfalkenof 1929 and that the engine was of significantly lower power than was considered necessary for a fighter by other nations in 1942, it turned out to be a remarkably good aircraft. Intended to roughly match the performance of contemporary Spitfire and Bf 109 models when the design was finalised, designer Bo Lundberg had admirably stretched what was possible with the limited power of the R-1830 to achieve just that. With barely more than 1000 hp available from the STWC-3, the J 22 possessed decent performance and its handling was highly praised by pilots.

![Data Sheet] FFVS J-22 - Fighters - War Thunder - Official Forum](https://i0.wp.com/cdn-live.warthunder.com/uploads/1b/a24dd2c6c6d940efffb0d267c4a163450c1751_mq/ffvs+j+22+jaeger-schweden+%289%29.jpg.5161142.jpg)

Looking somewhat like an unholy union between an Fw 190 and an F8F Bearcat, the J 22 was touted as being the fastest aircraft in the world ‘relative to engine power’. Though this was not true (the Mark I Spitfire was faster still with an engine of roughly the same rated power output), the J 22 was no slouch, though it must be admitted that by the time the first of the 198 production J 22s entered service in October 1943 its performance was not quite level with the world’s best. Nonetheless, when tested in mock combat against the P-51D Mustang (J 26) after the war the J 22 could reportedly hold its own at low and medium altitude. The power of the Twin Wasp copy fell off abruptly over 15,000 feet and this was probably the type’s most serious flaw. Its armament was also underwhelming, initially two 13.2mm (0.52in) Akan M/39A and two 8mm machine guns, later aircraft had four 13.2mm guns which was better (but still somewhat lacking).

The J 22 makes for an intriguing comparison with two other aircraft produced by nations with limited fighter experience, Australia’s Commonwealth Boomerang and Finland’s VL Myrsky. All three were designed and built to make up for an uncertain supply of foreign designs, were intended to be simple to build and maintain, all used the R-1830 Twin Wasp and all three were surprisingly effective. The J 22 was the fastest of the lot and proved popular and reliable, had it been produced in a different time by a nation not categorically wedded to the idea of neutrality, it may well have proved a successful export, being quite fast, simple, and reliable. As it was the J 22s served Sweden until 1952 and arguably more importantly gave the Swedish Aircraft Industry invaluable experience that it would put to good use in the years to come. Three are known to survive, one in taxiable condition, and another is being restored to fly.

4. Saab 32 Lansen (1951)

Hermann Behrbohm was a German mathematician who had worked for the Messerschmitt aircraft company from 1937. He contributed to high-speed trials of the Bf 109 fighter, and the development of the Me 163 and Me 262. His colleagues included the great Alexander Lippisch, father of the modern delta wing. Behrbohm’s most influential work was on the P.1101 fighter series, conceived as part of the Jägernotprogramm emergency fighter programme of 1944. This unflown remarkable jet fighter design, with its nose-mounted air intake and swept wings would inform the post-war F-86, MiG-15 and the Swedish Lansen. Following the war, Behrbohm was much sought after by nations wishing to harvest his remarkable know-how. He chose to move and work in Sweden. His influence on the Saab 32 Lansen, an attack aircraft built to replace the B 18, saw the aircraft adopt an exceptionally clean aerodynamic form. It is said to be the first aircraft created with a fully detailed mathematical model of its outer-mold line. The aircraft was capable of supersonic flight in a shallow dive. Behrbohm would also work on the Draken and Viggen, notably on the latter’s canard-delta form.

3. Svenska Aero Jaktfalken (1929)

After landing the Jaktfalken, Swedish Air Force test pilot Nils Söderberg declared“this is the best aircraft that I have flown so far”. The influence of Germans in Swedish aircraft is a recurrent theme, the Jaktfalken is no exception, as it was designed by the German Carl Clemens Bücker (famous for his Jungmann and Jungmeister). It was a world-class fighter but was never ordered in numbers, it won a single export order from Norway, and by single we mean one aeroplane.

2. SAAB 90 Scandia (1946)

Many nations’ aircraft industries grew fat and strong from the glut of wartime orders, and aeroplane production reached an all-time high. Sweden was no exception. In fact, being neutral and mostly spared from heavy strategic bombing (apart from that one time the Soviets had a go at Stockholm) its industry needn’t worry about such trifling matters as production lines being reduced to dust and cinder. When the war ended, SAAB’s future became uncertain. What would they do without the threat of an imminent invasion motivating combat aircraft production on a massive scale? What would they do with all their employees in the factories and design rooms? The good folks at SAAB, decided the only sensible thing to do was to branch out into the civilian sector and create the other SAAB (Svenska Automobil Aktiebolaget) as well as putting the original SAAB (Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget) to work building the most modern, comfortable airliner in the world: the SAAB 90 Scandia.

Carrying thirty passengers up to 650 miles at a 211 mph cruise speed and up to 279mph in a hurry, the Scandia featured novelties such as a tricycle landing gear, and an airfoil designed using NACA profiles. Its two 1820hp Pratt & Whitney R-2180-E twin wasp radial engines provided ample power, allowing a loaded Scania to take off on just one engine. This of course drastically improved safety, especially in the take-off and landing phases, safety was further enhanced by the superior pilot view provided by the tricycle gear. The Scandia improved upon all the best qualities of the 1930s era DC-3 which was the airliner at the time. Entering production in 1946, SAAB had a real winner on its hands.

Except there was one little thing the execs at SAAB had overlooked. Or rather, there were 10,781 things that they had overlooked. That’s how many DC-3s and C-47s were built in total and now that the war was over, they were being sold for practically nothing. There was simply no way for SAAB to compete with those kinds of numbers and it looked like the future was again dark for the Swedish aeroplane manufacturer. Luckily for them, the start of the cold war meant SAAB soon received an order for 661 J-29 fighter jets. The Scandia was put aside after a meagre 18 were built and fell into obscurity.

The SAAB 90 did fly for Aktiebolaget Aerotransport (ABA) from Sweden, but spent most of its career in the warmer climate of the jungles of Brazil, in the service Viação Aérea São Paulo S/A (São Paulo Airways) until 1969.

–– Sebastian Craenen

1. Saab 35 Draken (1955)

That the Draken was a decent candidate for the best fighter in operational service in 1960 is a huge accolade for Sweden, and the result of the nation’s extremely smart defence policy of the 1950s. The Royal Swedish Air Force realised that any chance of survival against a Soviet invasion depended on departing air fields at the first whiff of war and hiding in the sticks. It was apparent that large fixed airbases were easy to locate and attack, so the Swedish Air Force went ‘off-base’. The Draken was intended to employ an indigenous jet engine design, the STAL Dovern, which was tested on a Lancaster. But the British Rolls-Royce Avon, which would also power the Lightning, was deemed a superior choice.

The policy of domestic aircraft creation has always been extremely costly and vulnerable to cancellation by politicians seeking to save money. Whereas the US could afford cost overruns, Swedish aircraft projects were under a lot more scrutiny (this continues to the present day).

Though initially excellent, the J 29s introduced in 1951 would struggle to effectively counter the fast Soviet Tu-16 bombers coming into service in 1954. With excellent foresight, work on a faster replacement for the J 29 had begun before the Tunnen had even entered service. The next fighter was to feature a radical new wing design, a world-leading datalink and would be easy to maintain and operate from reinforced sections of motorway. It would also be extremely swift, at mach 2, around twice as fast as the J 29. This remarkable project seemed to be going extremely well –– and then along came Wennerström.

During the 1950s, Swedish air force Colonel Stig Erik ‘The Eagle’ Constans Wennerström leaked Swedish air defence plans, including a wealth of information about Saab Draken fighter jet project, to the Soviet Union. Security forces suspected him and employed his maid as an agent who discovered rolls of films hidden in his house. Despite Wennerström’s treachery the Draken emerged as a remarkably effective machine. The wing was an absolute masterpiece of aerodynamics, an avant-courier of the LERX of the later F-16, MiG-29 and Hornet which gave the aircraft performance far exceeding the expectations of international observers. On half the installed the thrust of a Lightning, the Draken offered similar performance, three times the air-to-air missile weapon load and a far longer range. Not only that, it managed to achieve this remarkable performance with fixed air intakes, a fact that is often overlooked.

Then there’s the ability to ‘cobra’ by turning off the flight control limiters, known to the Swedish pilots who discovered this as “kort parad”, or “short parry“. And there’s the infra-red sensor – and the datalink. All of which added up to a remarkable whole. The Draken was a masterpiece of strategic thinking, aeronautical design and engineering.

(Special thanks to Tony Ingesson)

Top 12 Dictator’s Aircraft

You cannot be a world-class psychopathic narcissist unless you have your own aircraft. Now, while one man’s ‘strong leader’ is another’s dictator we can be certain that all the human entrants in this list are or were prize bell-ends. Stephen Caulfield chooses 12 infamous aeroplanes that have perfected despot delivery.

12. Fokker F28 Fellowship Kalayaan (Republic of the Philippines)

Autocrat or not, the leader of an archipelago nation has good reason to fly. Hence, the Philippine people find themselves supporting the 250th Presidential Airlift Wing. That unit operated a Fokker F28-3000 Fellowship for state executive purposes starting in the stupidly decadent days of the Marcos family. The Fellowship was replaced only last year with a brand-new Gulfstream G280. This new aircraft lends a much slicker, up-to-the-minute corporate look to the law-and-order strongman presiding over a nation where vast economic inequalities are entrenched in daily life.

Non-political technical point: F28s feature a split tail cone air brake like that on a Blackburn Buccaneer strike aircraft.

11. Hawker-Siddeley HS-121 Trident

People’s Republic of China

Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou-en-lai shared a British-built Trident airliner. The Trident supplemented, and then replaced, an Ilyushin Il-18 Coot. Zhou-en-lai was the first Premier of China and served as Mao Zedong’s right hand. They were among the post-war world’s longest serving leaders, lasting from 1949 until the days of the Sex Pistols. Considering the poverty and turmoil of China in these years the idea of leaders looking down at the put-upon masses from a private jet strikes one now as something Communism would have eradicated. Or at least limited to really, really special occasions. Oh well, plus ca change. Though to be fair, the Trident was used as a domestic aircraft by the state owned airline CAAC who had a fleet of about 35. Having a British-made VVIP plane wasn’t entirely about looking down on the masses as China is a big country and the leadership needed to get around, but the optics were still far from perfect.

Once a common sight flying between the UK and western and southern Europe none remain in service anywhere. China’s VIP transport example bounced around for a time after retiring. Last word, the tired Trident was being dragged off from the shopping mall where it had been on display. It was increasingly found to just be in the way of people parking their BMWs. China’s all-business political elites now have access to Boeing 747s.

Non-political technical point: the Trident began life as a de Havilland design referred to as the DH.121

10. Airbus A319 (Bolivarian State of Venezuela)

Does oil and gas wealth ever bring a country happiness? Ignoring the Black Swan of Norway, consider Venezuela. In 2002 twelve protesters are gunned down by security forces loyal to President Hugo Chavez. Days later, he takes delivery of an Airbus. Apparently he’d seen one owned by an Emirati Sheik at some international conference. One phone call and US$65 million later he has a replacement for the ageing Boeing 737 he’d been putting up with. This and the massacre of his own citizens became twinned unforgivable moments for the majority of Venezuelans. Many of whom live in utter poverty despite the country’s huge fossil fuel reserves. The military then remove Senor Chavez from power. Two days later he’s back in office. He keeps the Airbus and some other privileges until his death from cancer in 2013. George Orwell weeps. So do a few others.

Non-political technical point: the A319/A320 program was a pioneer of commercial fly-by-wire and side stick control systems.

9. Airbus A340 (State of Libya)

Moammar Gadaffi typifies the classical career path of dozens of post-1945 liberationist revolutionaries who morphed into police-state despots. While seemingly an eccentric individual he ruled the masses with the an unimaginative mix of bribery and deep brutality. He relied on a privileged clique of family and close confidants to maintain power for forty-one years. None of this nonsense ever ends well. To wit, his last official plane has been rotting at an airport in southern France for years now. Another thriftless monument to dictatorship in a world littered with them. His choice of such a full on machine capable of transoceanic journeys seems a little off, too. This guy was welcome in fewer and fewer places worth visiting until his death at the hands of angry rivals in 2011. Grey leather sofas, a luxury suite with shower and a flat-screen TV should have made this jetliner a quick sell but post-coup legalities have complicated its disposal.

Non-political technical point: the A340 was the world’s longest airliner until the Boeing 747-8 appeared.

8. Ilyushin Il-62 Classic Chammae-1

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

It’s unclear what level of interior customization Chairman Kim Jong-Un’s official aircraft has been given. A safe bet is something superior to what you experienced on your last flight. Kim Jong-Un’s father used this handsome plane, one of only three designs ever configured with four engines mounted in twin nacelles under a T-tail. It seems everything in North Korea is subsumed into a military- and prison-industrial complex of the harshest kind. So, planning for a new airplane for the dictator of North Korea is probably the least excessive thing on the go there at the moment. North Korea is a hefty importer of cognac, luxury cars and pianos. This suggests an epic hypocrisy by the elites behind an old school Stalinist facade. Until a Prague Spring arrives in Pyongyang we won’t know the truth around this aircraft, it’s VIP passengers or the country employing it. What an unfortunate use for a wonderful plane. Bigger and faster than a Vickers VC-10 the Il-62 continues to impress.

Non-political technical point: the Il-62’s first Aeroflot passenger run was in 1967 with a non-stop trip from Moscow to Montreal.

We sell fantastic high quality aviation-themed gifts here

7. Boeing 707

Socialist Republic of Romania

A dictator’s aircraft you could actually go online and buy this year! You’d have had to outbid a private aerial refuelling contractor to get it. In storage for years, this 707 was bought by Omega Air and converted to approximate a Boeing KC-135 aerial refuelling tanker. The opportunity for this was, ahem, dictated by the underperformance of USAF programmes intended to replace their fast-ageing KC-135s. Where to start with the ironies? A long-time Marxist leader travelling about in a symbol of western privilege and consumerism from the heyday of mid-century air travel? Now it’s a privately-owned gas truck for the Pentagon in its so-called ‘Forever Wars’. As Ceausescu’s nepotistic regime became unpopular he imposed a ferocious austerity with a cruel rationing of daily essentials for the masses. His cult of personality falters and collapses. His own country is left an economic cripple and international pariah. Even Moscow starts to find Ceausescu repellent and before long a coup sweeps him from power and into the next world with a bullet. Unlike the Shah of Iran, Ceausescu, and his equally detested wife, were not able to flee in their luxury, long range airliner with a custom interior said to be equal to America’s Air Force One.

Non-political technical point: the tube protruding forward from the top of the 707’s vertical tail is an HF radio antenna.

6. Boeing 747

Imperial State of Iran

From 1953 until 1978 Iran was perhaps America’s single most important client state. Washington took its management of the oil-rich, strategically-placed nation with extreme seriousness. Braced by US patronage and unchecked police brutality, Shah Reza Pahlavi ruled Iran for a quarter century.

Oil and gas export revenue let Iran spend lavishly on infrastructure and imported food and weapons from the west. In such a reality a wide-bodied, twin-aisle, two-deck passenger jet would have seemed like a natural platform for conversion into a super-luxury air yacht for the Shah.

By 1978, he had done so much harm he managed to trigger an unstoppable Muslim fundamentalist counter attack. The collapse of US-Iranian relations sent shock waves through the Middle East. Indeed the world felt them and continues to watch the Persian Gulf with a weary geopolitical eye. How bad had it all gone by 1978? Well, the man who modelled his governance on the great Persian emperors had to flee for his life in that personal Jumbo Jet. The one with gold toilet fittings.

Non-political technical point: maximum takeoff weight for -200 and -300 series 747s is equal to about 378 Jaguar E-type FHC sports cars.

Save the Hush-Kit blog. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Thank you.

5. Ilyushin Il-96-300PU

Russian Federation

Oil and gas revenue mixing with nationalist oligarchy results in some interesting privileges for the ones in charge. Post-Communist Russia is no exception. Rappers, Saudi Princes, upper echelon athletes, tech billionaires, hedge fund managers and even Donald Trump may have something to envy in Vladimir Putin’s executive airplane. With its sheer size, long range and very shiny interiors this aircraft embodies concentrated political and economic power in the age of a fractious global economy gone hog wild. Where a western lottery winner or mid-level celebrity gets an Embraer EMB-500 Phenom Vlad gets a flying five-star-plus hotel and command post. Naturally enough, the top dog in a nuclear-armed country physically larger than all others should have a hot, thoroughly modern aircraft at his disposal. This is absolutely what that looks like. Mr. Putin was elected, yes, but Russia’s recent backsliding on democracy and the fact he embodies the deeply historical Russian preference for ultra-strong leaders earns this ex-KGB officer and his ride a place on our list.

Non-political technical point: the long dorsal fairing on the 300PU model is not found on the commercial versions of the Il-96 and suggests an allocation of communications and protective electronic warfare systems deemed appropriate to Mr. Putin.

4. Mil Mi-8 Hip EW-001DA

Republic of Belarus

And here comes a chopper to chop off your head! So goes the nursery rhyme in 1984, George Orwell’s chilling novel of totalitarian life. Official news clips from Belarus this summer show us that novel will probably never be irrelevant. In them, we see President Victor Lukashenko flying back to Minsk in a Mil Mi-8, AKS-74U at his knee. Clad in a tactical vest we see the unsmiling leader of a nation in turmoil barking orders into a phone. He surveys a highway jammed with protestors he has earlier that day referred to as vermin. On the ground to oversee forceful countermeasures to a sustained democracy movement, Lukashenko stops to hail a squad of black-clad riot police. Having rigged his country’s last election to appear to have given him an 80% majority the autocratic and corrupt Lukashenko must now cope with a massive populist backlash. Delivering Eastern Europe’s equivalent of Tony Montana that day in August was an absolute classic of Soviet era helicopter development, a Mil Mi-8. The one-time workhorse of the Warsaw Pact is a wonderful platform and in the case of Belarus case probably highly effective in all the wrong jobs.

Non-political technical point: the ‘Hip’ series made its first flight in 1961 and is still in production making it the most-produced helicopter in history.

Here’s a new thing! An exclusive Hush-Kit newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. Hot aviation gossip, opinion, warplane technology updates, madcap history and other insights from the world of aviation by @Hush_Kit Sign up here

3. Dassault Aviation Falcon 900

Syrian Arab Republic

The brutal news from Syria’s civil war, amplified at every turn by foreign intervention, makes the presence of any luxury jet a bit of a mind-bender. And what a toy for the man residing over such a heartbreaking mess, Bashar al-Assad. At the factory gate in France a Falcon 900 is worth over US$40 million. Adding a luxury master suite with full bathroom and then communications and security gear for someone with a serious penchant for control and this aircraft comes to symbolise high privilege wrapped in a cloak of evil. Fast moving and capable of unrefuelled trips of many thousands of kilometres the Falcon is perfect for the diplomatic pouch and other high-level errands. Fleeing from disaster should also be easy in a Falcon. As long as you had a place to go and could trust the crew and your security detail, that is. Soon enough, neither may be a reasonable expectation for Mr. Assad.