The Empire’s Ironclad: Flying & Fighting in the B-52

Since its combat debut in Vietnam, the B-52 Stratofortress has unleashed more destruction than any other aircraft. Keith Shiban flew the ’52 in the nuclear deterrent role, and in combat missions over Iraq. We spoke to him about flying and fighting in this menacing enforcer of American foreign policy.

To keep this blog going- allowing us to create new articles- we need donations. We’re trying to do something different with Hush-Kit: give aviation fans something that is both entertaining, surprising and well-informed. Please do help us and click on the donate button above – you can really make a difference (suggested donation £10). You will keep us impartial and without advertisers – and allow us to carry on being naughty. A big thank you to all of our readers.

What were your first impressions of the B-52? I was awed by the size of it. You don’t realize just how big it is until you get up close to one. It looks powerful, even sinister with the dark camouflage and ECM blisters all over it.It’s not what I would call a ‘pretty’ airplane. It’s a purpose-built weapon of war and looks the part.

I had just come off instructing in the T-38 and it was like jumping out of a Corvette into an 18-wheeler. I didn’t find the B-52 difficult to fly, but I did find it hard to fly well. Nothing happens quickly and there is a lot of inertia to manage.

Deflect the yoke and there’s a noticeable pause before the plane starts to bank. Centre the yoke and it keeps rolling for a bit.

After my first training sortie I can remember looking back at this huge beast sitting on the tarmac and thinking “Damn, I landed that?”

Air refueling was for me the most difficult thing to learn. As an aircraft commander, that’s where you make your money. If you can’t get the gas from the tanker you can’t do the mission. It wasn’t until my seventh or eighth training sortie that I was actually able to stay hooked up to the tanker. The short-tail B-52s (G and H models) have a bit of a dutch-roll to them. It’s not really noticeable until you get right behind the tanker.

You have to constantly work the yoke just to keep the wings level during air refuelling. Once you finally get your muscle-memory programmed it becomes second nature, but it took a while to figure it out. Even then it’s still aworkoutt. Taking on a 100,000 pounds of gas meant being on the end of that boom for 20 minutes or so. I’d feel like I’d been workout out at the gym afterwards.

A B-52G Stratofortress aircraft takes off on its return flight to the United States after being deployed during Operation Desert Storm.

The other big adjustment was handling that large of a crew. The B-52 is very much a navigator’s airplane. I used to joke about me just being the voice-activated autopilot for the navigators.

In training, I was taught that the Aircraft Commander’s job was to “fly the plane and make decisions”. I had to constantly process inputs from the other crew positions and decide how to react. The offense team might be telling me to go one way to get to the target but the defense team might be telling me not to go that way because there’s a threat over there.

You lived or died as a crew. Even if the pilot is Chuck Yeager (and I’m not) it won’t do much if the Radar Navigator can’t hit the target or the Electronic Warfare Officer lets you get shot down on the way there. It was a team effort all the way. The aircraft commander tends to get all the credit but I was only as good as the rest of my crew. Fortunately I had a very good crew.

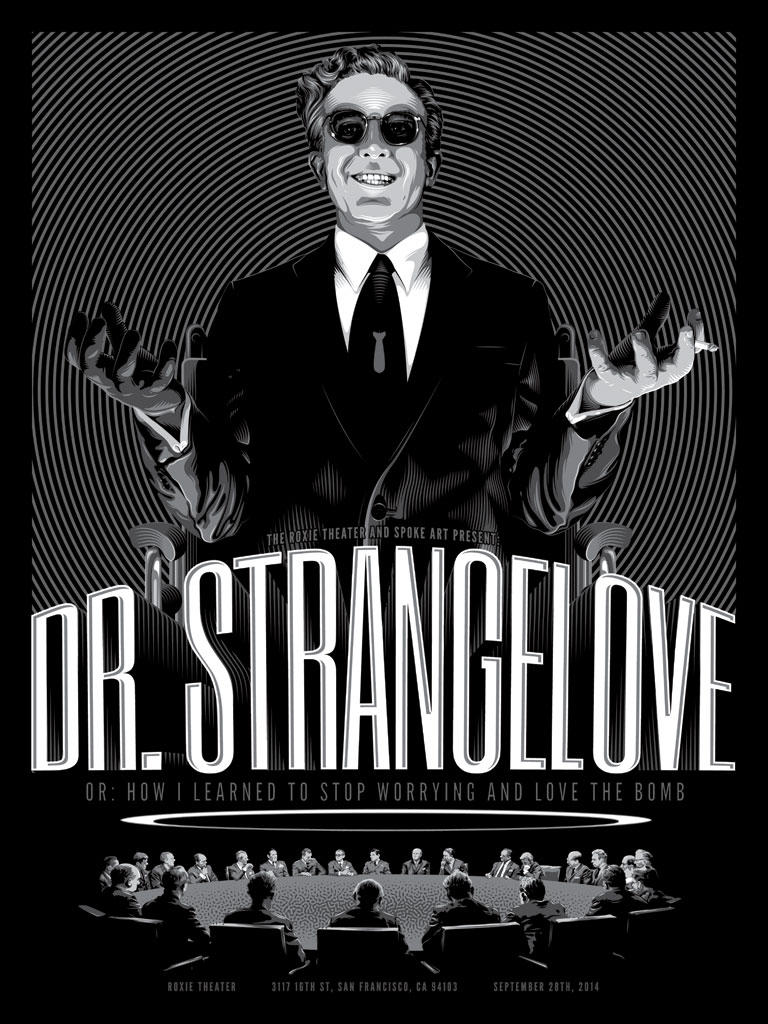

How do B-52 crews view Dr Strangelove- was it realistic?

Dr. Strangelove was a staple on alert. I’ve seen it enough times to have the script memorized.

Kubrick got an awful lot right with that movie, especially when you consider that the Air Force was very secretive about the B-52 at the time.

My main critique would be that the final bomb run seems to take up the last third of the movie, when in reality a bomb run doesn’t take nearly that long from Initial Point to release. I think they tried about eight different means of getting those bomb doors open. In reality there was a manual release cable that the navigators could pull to unlatch the doors. But hey, it’s a movie. They have to make it dramatic.

It’s still probably my favourite movie of all time.

What tips would you offer to new crews coming onto the ’52?

Be proud. You’re flying a piece of history. Even to this day, when we really want some other country to know we mean business, we deploy B-52s.

What kit did you wish for when you were serving on the B-52?

I would have liked more in the way of standoff weapons. In 1991 we were still mostly dropping iron bombs like in WWII. This required us to fly directly over the target. You can avoid most of the threats on the way to and from the target, but anything worth bombing is probably going to be defended. You can’t do much evasive action on the bomb run, because the whole reason you’re there is to hit the target. Even if the defenders don’t shoot you down, simply making you miss the target means you did all that work for nothing.

Please talk me through your first Gulf War mission

My crew was deployed in August of 1990 to Diego Garcia to be part of the 4300 Provisional Bomb Wing. I can remember getting the phone call early on a Sunday morning: “Be here in 4 hours with your bags packed. You’re going away indefinitely.”

After seven months of living on tiny atoll in the Indian Ocean, the part of me that wasn’t scared shitless was ready to just get the whole mess over with so I could go home.

It was around 5:00 PM when we got notified. I know this because the chow hall opened at 5 and I was getting ready to go eat. Someone banged on the door to the room four of us shared and said “You’re going.”

I forget how much time we had to get ready but I know I walked over to the dining hall and tried to eat something. My stomach twisted itself into a knot so all I all managed was to eat a bit of salad and sip some ice tea.

At the appointed time we were loaded onto a bus and driven down to the airfield. The security police gave us an escort with lights and sirens going, which I thought was pretty cool.

Have a look at this lovely model here

Have a look at this lovely model here

We had been previously briefed on what our Night One target would be. We would be hitting one of the Iraqi forward-deployment airfields. There were five of these roughly 25 miles from the border with Saudi Arabia. Three B-52s were tasked against each airfield plus we had a number of “airborne spares” in case one of the jets broke on the way there.

We were ushered into the auditorium for our pre mission briefings. Our pep talk from the commander was basically “Don’t run into the ground and do their job for them”. Good advice actually.

The mission briefings were pretty short since we already knew beforehand what the target was. We had done a few rehearsals against some islands out in the Indian Ocean so were pretty confident in our ability to do it.

I don’t recall exactly when we launched, but it was getting late in the day by the time we actually got out to the aircraft. We launched 20-some bombers and tankers completely by timing, without a single radio call being made. There was a scheduled time for engine start, taxi and takeoff for each aircraft.

A fully loaded B-52G is a sluggish beast and needs a lot of runway to get airborne. The runway at Diego was relatively short by SAC standards. Only 10,000 feet if I recall. We used up most of it by the time we lifted off.

There was a nasty line of heavy rain showers hitting the area right around then and we flew through some of it. I can recall taking a pretty good beating going through the weather.

A short while after we got leveled off we did our first air refueling. There were normally two air refuelings scheduled on the way up to the Saudi peninsula. The G model was a bit underpowered and the extra drag of having bombs on the wing pylons made it worse. Sometimes I would have the throttles to the firewall just trying to stay on the boom.

A good tanker crew could make you look good back there. If they were jinking around a lot, trying to stay in formation, it could make your job a lot tougher. If their autopilot wasn’t working it was even tougher. Our bow wave would actually move the tanker around. If either one of us wasn’t smooth on the controls it could cause a chain reaction.

Somewhere on the way up to Saudi Arabia we took time to don our survival gear and sidearms. We had flak vests, as I recall, but I think we placed them strategically around the cockpit rather than wearing them. We figured that anything likely to hit us would come up through the floor.

You probably want to know what I was feeling at the time. I am not a particularly brave individual. I was always pretty scared the days before a mission. Once I got in the jet I was fine. That was my comfort zone. No more worrying about if it’s going to happen, it’s happening now. Just do your job.

By this time I was very confident in our ability as a crew to do the mission. We did a lot of training in the six months prior and I knew I could fly the jet to its limits. Knowing that you’re probably going to get shot at in a few months gives you added incentive to train hard.

It was dark by the time we got up over Saudi Arabia. The sky was filled with the lights of aircraft massing for the attack. I can remember commenting on it, right before I fell asleep.

Now I’d to say that I’m such a steely-eyed warrior that I was able to sleep on way into combat but I think I was just exhausted at that point. I had been up most of the day, combined with the stress I think I just shut down.

Next thing I knew, my copilot was waking me up and telling me we needed to get ready for low level. This involved taping over all the lights in the cockpit with electrical tape and taping green chemical light-sticks under the dash to use as NVG lighting. Very high tech. Back then we had red cockpit lighting that would wash out the Night Vision Goggles. The goggles were not our primary method of flying low level but they were an addition to the terrain avoidance radar and the FLIR that were built into the aircraft. The goggles clipped to our helmet visor and had a battery pack mounted to the back of the helmet with velcro. The whole assembly was heavy and would snap your neck in an ejection – so you had remember to take it off before punching out.

Our formation at high altitude was 2 miles in trail with each aircraft stacked 500 feet above the one in front of it. As we dropped down to low altitude we went into what was called a “stream”. A bomber stream was normally spaced about a minute apart, roughly six miles at the speeds we flew low levels at.

We dropped down low well inside Saudi airspace so we wouldn’t get picked up by the Iraqi radars. Our tactics at that time were to avoid known threats. No sense tangling with a SAM site if you can just go around it. Of course it’s the one you don’t know about that worries you.

We were running between 300 and 500 on our way to the target. I remember it was pitch black that night and the NVGs weren’t really doing much for me as they need at least some ambient light to work. They were picking up all the anti-aircraft fire, however, and probably making it look closer than it actually was.

It looked to me like they were just trying to fill the air with lead and hope somebody flew through it. I can remember seeing a ZSU-23 spitting out tracers like a fire hose. Fortunately it wasn’t near us because one of those could ruin your day. I saw a lot of heavy stuff, 57mm and larger. I didn’t worry as much about those so much as they had a very low probability of actually hitting something.

I occupied myself with calling out what I was seeing to the crew and pointing out that it was either of range or not aiming at us. It’s hard to tell what you’re seeing at night. Was that light I just saw a missile or just a truck headlight?

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Save the Hush-Kit blog. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Thank you. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here

The actual bomb run was planned as a “multiple axis of attack”. The three bombers in our cell would come at it from three different directions to confuse the defenses. Sixty seconds was normally the spacing between aircraft but in this case we were compressing it to 45 seconds. The idea was to minimize our time over the target. Most critically, we would have to make our time-over-target with zero second tolerance or our bombs might frag the next guy over the target. The plan allowed no room for error.

My aircraft was loaded with fifty one cluster bombs that were filled with mines. The other two aircraft had British runway cratering bombs that we called a “UK1000”. The bombs would crater the runways and taxiways while the mines would make life difficult for anyone trying to repair them. The bombs also had a variable time delay so some of them would dig a hole and then blow up as much as a day later.

To release the cluster bombs we would have to climb up to 1000 feet going across the target. That is not a good altitude. You either want to be really low or really high. The other two jets were able to drop from 500 feet. We got the first run over the target so that we might at least have surprise on side.

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. This site is in peril as it is well below its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. A huge thank you if you have already donated and apologies for interrupting your read.

The bomb run itself was uneventful except for not being able to see anything. As soon as started releasing, things got interesting. In my NVGs I saw “Flash! Flash! Flash! Flash!” and I thought “Oh crap, they’re shooting at us and I can’t do a damn thing about it until we get the bombs away”.

As soon as the bombs were gone I went into an aggressive “gun jink” maneuver. This involved rapidly throwing the plane around in multiple directions. At the same time I pointed the nose back at the ground. We started picking up speed fast. Our limiting airspeed was 390 knots indicated and I’m sure I saw 430 on the gauge. At this point the plane was wanting to “mach tuck”. The faster we went the more the nose wanted to go down. I had to run the trim nose up quite a bit to counteract that. Meanwhile we’re jinking around low to ground at night, probably being a bigger threat to ourselves than anything the enemy might be doing.

What I probably saw that night was the charges from our own cluster bombs opening. The interval between flashes was just about right for it to look like a 37mm anti-aircraft gun. In 20/20 hindsight we probably weren’t getting shot at but I didn’t realize it at the time.

In all the excitement we turned the wrong way coming off target and ended up doing a 270 degree turn to get back on course. Meanwhile the other two bombers did their thing, followed up by a flight of F-15Es who took out the hardened shelters.

After that I was hyped up all the way to the Saudi border. The plan was for us to land at Jeddah International Airport in Saudi. I think we had to go around at least twice because the traffic pattern was so busy. Once we finally got on the ground some guys in silver hazmat suits checked the outside of our plane for contamination (chemicals). Then the maintenance guys checked us for battle damage and didn’t find any. Finally we got to park the jet. I can remember sitting on the ramp at Jeddah for a very long time waiting for someone to come get us. We didn’t really care, we were just happy to have accomplished the mission and still be alive.

Tell me something most people get wrong about the B-52

Most people assume that something as large as a B-52 must be roomy on the inside. In reality it’s quite cramped in there. Most of the available space is taken up either by fuel tanks, bombs or electronics. The only place you can even stand up straight is the ladder between the upper and lower compartments.

Unlike an airliner, it’s also extremely noisy. We had to wear headsets or helmets all the time to protect our hearing. Talking “cross cockpit” like we do in an airliner was impossible. Everything had to be said over the intercom.

Not a comfortable place to spend 12 to 16 hours. Even training missions would leave you completely drained physically. SAC liked to say “You’ve got to be tough to fly the heavies”.

Tell me something most people don’t know about the B-52

I don’t think our role in the Gulf War was ever well publicized. Especially the low level strikes that were carried out on the first three nights.

During the Cold War, did members of the B-52 aircrew community feel confident that they would survive an attack on the USSR?

That’s the big question, isn’t it? Fortunately we never had to find out.

Soviet air defenses were quite formidable. Our ECM package in the G-model wasn’t as good as what the H-model has. There were some newer Soviet missiles, like the SA-10 (S-300) that we simply would not have wanted to meet. We also feared running into a MiG-31 long before we even got to Soviet territory.

You have to realize though, that by the time we got there both sides would likely have been lobbing ICBMs at each other for eight hours. There may not have been much left of their air defenses to worry about.

9. You stood nuclear alert- how does one reconcile personal ethics with the knowledge one may have carry out a nuclear attack?

We were so well trained that we’d have probably been halfway to our targets by the time we even thought about what we were doing. We used to joke about turning south and making Jamaica the next nuclear power if the balloon went up but that was just a joke.

Most of didn’t think we’d have to do it. The whole reason SAC existed was to prevent a war with the Soviets. If things had gotten that bad, we’d have probably been dodging nuclear explosions on our way out of US airspace. The instinct would have been to hit them back with everything we had at that point.

Still, it was sobering to sign for an alert aircraft with sixteen nuclear weapons on it. Quite a lot of responsibility for a 27-year-old aircraft commander.

What were your favourite and least favourite flights/missions on the B-52?

I enjoyed doing anything tactical like low levels or playing with fighters. Touch and go landings were fun but I think SAC overdid it sometimes. We’d fly an 8 hour training mission and then have 3 hours of “transition” as it was called tacked on. We’d already be worn out from flying all night and they’d want us to practice landings from 1 AM to 4 AM. It was especially rough on the other crewmembers, who were just along for the ride at that point.

Why do you think the B-52 has stayed in service for so long?

In some ways it’s such a generic aircraft that it can be adapted to different missions. It can carry a lot of ordnance a long way and it can loiter for a long time. One thing people don’t always think about is it has a tremendous amount of electrical power from its four generators. That allows them to keep stuffing new electronics into it.

What do you think of its Russian equivalent, the Tu-95? When the Russians make something that works they stick with it. I’ve had the opportunity to crawl inside one. Like the B-52 it was a mix of very old and very new technology. It’s smaller than a B-52, about 2/3 the size. It’s extremely fast for a turboprop aircraft and also very efficient. Those props produced a tremendous amount of noise and vibration. I can only imagine that it gave the crews a real beating over time. Tactically I don’t think they were anywhere close to what we were doing in the B-52. I don’t believe they ever envisioned using the Tu-95 as a low-level penetrator.

Did you ever fly at low altitude in a B-52?

Low level was our bread and butter in the B-52 community at that time. We were still training to penetrate Soviet air defences in the late 1980s.

In the daytime it was a lot of fun, at least for the pilots. I don’t know how the other crew positions managed to sit through it. Sitting in the dark while getting bounced around on a hot day was a recipe for airsickness. B-52 navigators are a very dedicated bunch. The downward firing ejection seats the navigators rode in couldn’t have inspired much confidence either.

At night it was very challenging. Our systems were good down to 200 feet over flat terrain and I think 300 or 400 feet in mountainous terrain. Keep in mind that our wingspan was almost 200 feet. A night low level required a tremendous team effort, especially between the pilots and navs. It was all hand flown in the B-52. Unlike the B-1 and F-111, we only had “terrain avoidance” radar. It wasn’t coupled to the autopilot. So imagine you’re bopping along at 360 knots through the mountains in the middle of the night.

The SAC tactics people interviewed a Soviet MiG-29 pilot who had defected. The asked him “Do you think you could intercept a B-52 flying 300 feet at night in terrain?” He told them “No fucking way”.

You may also enjoy 11 Cancelled French aircraft or the 10 worst British military aircraft, Su-35 versus Typhoon, 10 Best fighters of World War II , Su-35 versus Typhoon, top WVR and BVR fighters of today, an interview with a Super Hornet pilot and a Pacifist’s Guide to Warplanes. Flying and fighting in the Tornado. Was the Spitfire overrated? Want something more bizarre? Try Sigmund Freud’s Guide to Spyplanes. The Top Ten fictional aircraft is a fascinating read, as is The Strange Story and The Planet Satellite. The Fashion Versus Aircraft Camo is also a real cracker. Those interested in the Cold Way should read A pilot’s guide to flying and fighting in the Lightning. Those feeling less belligerent may enjoy A pilot’s farewell to the Airbus A340. Looking for something more humorous? Have a look at this F-35 satire and ‘Werner Herzog’s Guide to pusher bi-planes or the Ten most boring aircraft. In the mood for something more offensive? Try the NSFW 10 best looking American airplanes, or the same but for Canadians. 10 great aircraft stymied by the US.

You may also enjoy top WVR and BVR fighters of today, an interview with a Super Hornet pilot and a Pacifist’s Guide to Warplanes. Want something more bizarre? The Top Ten fictional aircraft is a fascinating read, as is The Strange Story of The Planet Satellite. Fashion Versus Aircraft Camo is also a real cracker.

Most informative!

I really do love hush kit and Major Kong’s blogs, so it’s great to see them together!

A fascinating article, but you didn’t ask the most important question of all; “Where the hell is Major Kong?”

I dont see the Pilots name? I was there. Scoob says Hi! Fox4

Hi Scoob, it’s in the second line (Keith Shiban). I’d love to interview you about your flying. Cheers, Joe