CANCELLED: The 10 best aircraft of World War II that never saw service

Vrooom! The MB.3 was spectacular but is it the best of our cancelled aircraft?

Hindsight is a glorious thing. From the safe distance of several decades it is blindingly obvious that many of the aircraft thrown into the maelstrom of combat during the Second World War were worse than useless and should never have been built (Messerschmitt Komet, Blackburn Roc, Breda 88, I’m looking at you). Rarer and more obscure today are the outstanding aircraft that never made it. Despite their brilliance, due to politics or bad timing or official indifference or bad luck, these potentially superb aircraft never got the chance to shine.

To assist the casual reader I have defined the eight most popular cancellation reasons below and assign them to each of the aircraft in question in a vaguely Top-Trumps-esque fashion:

Engine unavailable

Inexplicable official indifference

Death of designer (and/or other significant personage)

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already

No spare industrial capacity

Bad timing

Teething troubles

Politics

Now read on!

10. Miles M.20

The chunky, cheap and cheerful Miles M.20 would likely have proved a most useful aircraft in the early/mid war period.

The M.20 was a thoroughly sensible design, cleverly engineered to be easy to produce with minimal delay at its nation’s time of greatest need, whilst still capable of excellent performance. As it turned out its nation’s need never turned out to be quite great enough for the M.20 to go into production. First flying a mere 65 days after being commissioned by the Air Ministry, the M.20’s structure was of wood throughout to minimise its use of potentially scarce aluminium and the whole nose, airscrew and Merlin engine were already being produced as an all-in-one ‘power egg’ unit for the Bristol Beaufighter II. To maintain simplicity the M.20 dispensed with a hydraulic system and as a result the landing gear was not retractable. The weight saved as a consequence allowed for a large internal fuel capacity and the unusually heavy armament of 12 machine guns with twice as much ammunition as either Hurricane or Spitfire. Tests revealed that the M.20 was slower than the Spitfire but faster than the Hurricane and its operating range was roughly double that of either. It also sported the first clear view bubble canopy to be fitted to a military aircraft.

In its final form as a potential Naval aircraft, the M.20 sported smaller undercarriage fairings and a lengthened rear fuselage.

Because it was viewed as a ‘panic’ fighter, an emergency back-up if Hurricanes or Spitfires could not be produced in sufficient numbers, production of the M.20 was deemed unnecessary since no serious shortage occurred of either. However, given that much of the development of the Spitfire immediately after the Battle of Britain was concerned with extending its short range, as the RAF went onto the offensive over Europe, the cancellation of a quickly available, long-ranged fighter with decent performance looks like a serious error. Exactly the same thing happened with the Boulton Paul P.94, which was essentially a Defiant without the turret, offering performance in the Spitfire class but with heavier armament and a considerably longer range. The only difference being that this aircraft was even more available than the M.20 as it was a relatively simple modification to an aircraft already in production.

Oh dear. The M.20 looking rather sorry for itself after overshooting on landing and ending up in a gravel pit.

The M.20 popped up again in 1941 as a contender for a Fleet Air Arm catapult fighter requirement, where its relative simplicity would have been valuable. Unfortunately for Miles, there were literally thousands of obsolete Hawker Hurricanes around by this time and with suitable modifications they did the job perfectly well.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Inexplicable official indifference,

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 3 will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit, exclusive new articles, explosive photography, and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes 3 here.

9. Fiat G.56

There are three known photographs of the Fiat G.56. This is one of them.

The G.56 had the misfortune to emerge after the country it was built for had temporarily ceased to exist. Italy’s aircraft industry was wholly located in the new Italian Social Republic, formerly the north of Italy, which was a German puppet state nominally ruled by Mussolini. As a result Italian aircraft design and production after mid 1943 was largely undertaken under German oversight.

Fiat’s earlier G.55, of which some 300 were built, had been rated by a German test commission as the best fighter in the Axis and Kurt Tank (designer of the superlative Focke-Wulf Fw 190) had nothing but praise for the aircraft after he test flew one in late 1943. The G.56 was essentially the same airframe mated to a considerably more powerful Daimler Benz DB 603 engine, this engine was considered too large to be fitted into the Messerschmitt Bf 109, and the Fiat was seen as a leading contender to use it. Daimler Benz accordingly supplied three DB 603s to Fiat in Turin and the first prototype G.56 flew in March 1944.

There are no known photos of the G.56 in flight so here are a pair of G.55s enjoying the postwar era. The two aircraft were virtually indistinguishable externally.

It was clear from the start that this was a terrific fighter, it was very fast, with an official top speed of 426 mph (the highest to be attained by an Italian designed fighter during the war), yet it retained the superlative handling that had so impressed Tank and other German test pilots. Unlike most Italian fighters, it was very well armed with three (German) 20-mm cannon, one firing through the propeller hub, the others in the wings. In official tests it proved to be superior to the Messerschmitt Bf 109K, Bf 109G and the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 and there was considerable German interest in the aircraft at even the highest levels. However, Italian production methods were not up to German standards and the man-hours required to build the Fiat were seen as prohibitive. Furthermore German industry was producing precious few DB 603s as it was and supplying them to a potentially unreliable ally when Germany’s war was rapidly going downhill seemed an unacceptable risk.

As a result G.56 production was never seriously contemplated by the German authorities, the DB 603 was used in a modified Fw 190 instead (the Ta 152), and only two examples of Fiat’s brilliant fighter ever saw the light of day.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Engine unavailable,

No spare industrial capacity,

Politics

8. Mitsubishi Ki 83

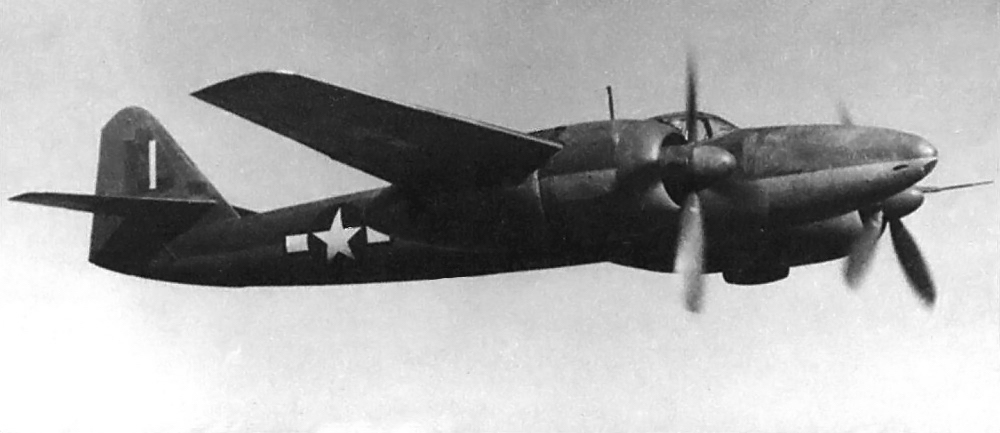

Most of the handsome and impressive Ki-83’s flying career was in American hands.

Produced by a team under Tomio Kubo, who had earlier designed the superlative Mitsubishi Ki-46 reconnaissance aircraft, the Ki-83 could have been the finest twin-engined fighter of the war. As things turned out it became an obscure footnote in aviation history.

The result of an Imperial Army specification calling for a high altitude, long-range heavy fighter the aircraft that emerged from Mitsubishi’s experimental workshop was possibly the most aerodynamically clean radial engined aircraft ever built and possessed spectacular performance. As well as recording the highest speed attained by any Japanese aircraft built during the war, the Ki-83 was blessed with remarkable agility for such a large aircraft and was fully aerobatic at high speeds. It is recorded to have been capable of executing a 2200 feet loop at 400 mph in 31 seconds. Compared to its direct US equivalent, the F7F Tigercat which also failed to see service during the war, the Ki-83 had the same range but was faster and more manoeuvrable. Armament comprised the potent combination of two 30-mm and two 20-mm cannon, all firing through the nose. Unfortunately for this superlative warplane, its timing was appalling.

From this angle the small window in the fuselage for the optional second crew member is visible just above the tailplane. The outlet at the rear of the nacelle is the turbocharger exhaust.

First flown in November 1944, tests were often interrupted by American air raids and of the four prototypes known to have been completed, three were damaged or destroyed by bombing. The crippling raids by B-29 Superfortresses were also the reason that the Ki-83 never entered production: despite the enthusiasm of both the Army and Navy, by the time it was flying all aircraft manufacturing was focused on interceptors to combat the B-29 and the Ki-83 never received a production order. After the war the sole surviving prototype was evaluated in the US and received glowing praise. With the higher octane fuel available in America the Ki-83 ultimately recorded a speed of 473 mph. Despite being earmarked for preservation the only Ki-83 to survive the war and arguably the finest wartime fighter produced in Japan was last recorded at Orchard Field Airport in Illinois in 1949. It is presumed to have been scrapped there in 1950.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

No spare industrial capacity,

Bad timing

7. Focke-Wulf Fw 187 ‘Falke’

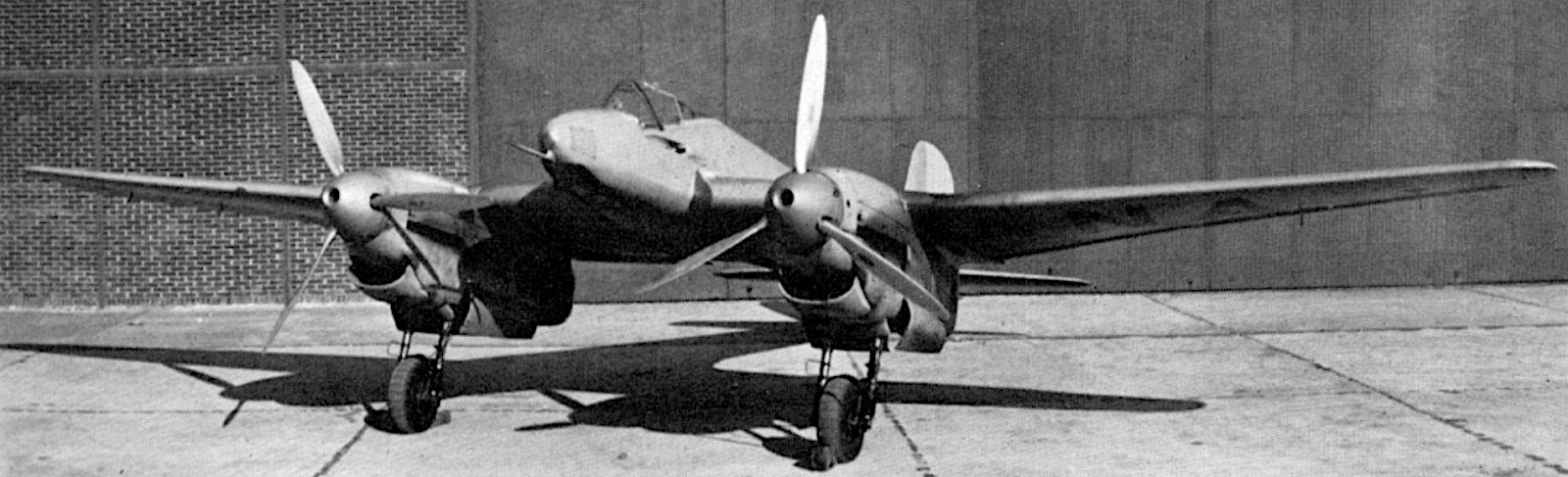

Viewed from ahead it is immediately apparent how tiny the Fw 187’s fuselage is. Note where the pilot is looking, some instruments were fitted to the sides of the engine nacelles due to lack of space in the cockpit. The same approach was employed on the Henschel Hs 129 and the Falke’s arch rival, the Messerschmitt Bf 110.

An exceptionally fast aircraft, the handsome Fw 187 suffered as a result of the Luftwaffe having very precisely defined and limiting concepts of what they required from a twin engine aircraft. It is often regarded as having been a direct competitor to the Messerschmitt Bf 110 but the truth is rather less straightforward.

Kurt Tank designed the Falke as a long range single-seat escort fighter. It was both smaller and lighter than the Bf 110 and was broadly equivalent to the British Westland Whirlwind. The new twin was designed as a private venture and was undoubtedly, a fine aircraft. Unfortunately for Tank the Luftwaffe saw no use for such a machine, being convinced that their high-speed bombers were fast enough to avoid any serious threat from defending fighters. The specification they demanded for twin-engine fighters was for larger, heavier aircraft in the so-called ‘zerstorer’ class epitomised by the Bf 110. However, the head of the Luftwaffe’s technical division, Wolfram von Richthofen (brother of top scoring First World War ace Manfred von Richthofen) was personally not convinced that bombers would remain faster than opposing fighters for long and personally approved prototype construction. Germany at the time was painfully short of aero-engines, and instead of the DB 600s he had wanted Tank had to make do with the Jumo 210 which was some 200 hp lower powered.

The first prototype complete with its relatively low-powered Jumo engines and single-seat cockpit.

Purposeful and very fast, was the Fw 187 a war-winner?

Whilst it is unlikely that the Fw 187 would have significantly changed the course of the war, its notably better performance than the Bf 110 and significantly better range than the Bf 109 would have been useful indeed during the Battle of Britain. How well it would have coped in combat with the Hurricane and Spitfire remains open to question, twin-engine fighters generally fared less than spectacularly throughout the war when faced with modern single-engine fighters. However, as well as being faster than both British fighters, Heinrich Beauvais, Luftwaffe Chief Test Pilot, claimed that its turn rate was comparable to the Bf 109 and its rate of roll was only slightly inferior which seems to suggest that in 1940 it would have been a formidable opponent indeed and a another wasted opportunity for the Luftwaffe.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Engine unavailable,

Inexplicable official indifference,

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already

6. Grumman F5F ‘Skyrocket’

Better than a Spitfire? Maybe. Better looking? Hmmmm….

There are five more F5Fs in this picture than ever existed in reality.

With no nose to obscure the pilot’s view ahead and downwards it’s pretty obvious why the F5F was described as a ‘carrier pilot’s dream’

With wings folded the F5F was almost unbelievably compact for a twin-engine aircraft.

Neither of these issues would have killed the F5F if it hadn’t been for the demands of the early war period. The F4F was good enough for the time being and Grumman was busy churning them out in huge numbers to ever more demanding contracts, whilst at the same time desperately working to get the Hellcat into service (and more importantly not conceding orders to the Corsair). With this sort of pressure afflicting Grumman, sorting out the rather exotic Skyrocket was not a priority. Ultimately the portly F5F performed its most important work flying as a development aircraft for the impressive F7F Tigercat which entered service in August 1945.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Inexplicable official indifference,

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already,

No spare industrial capacity,

Teething troubles

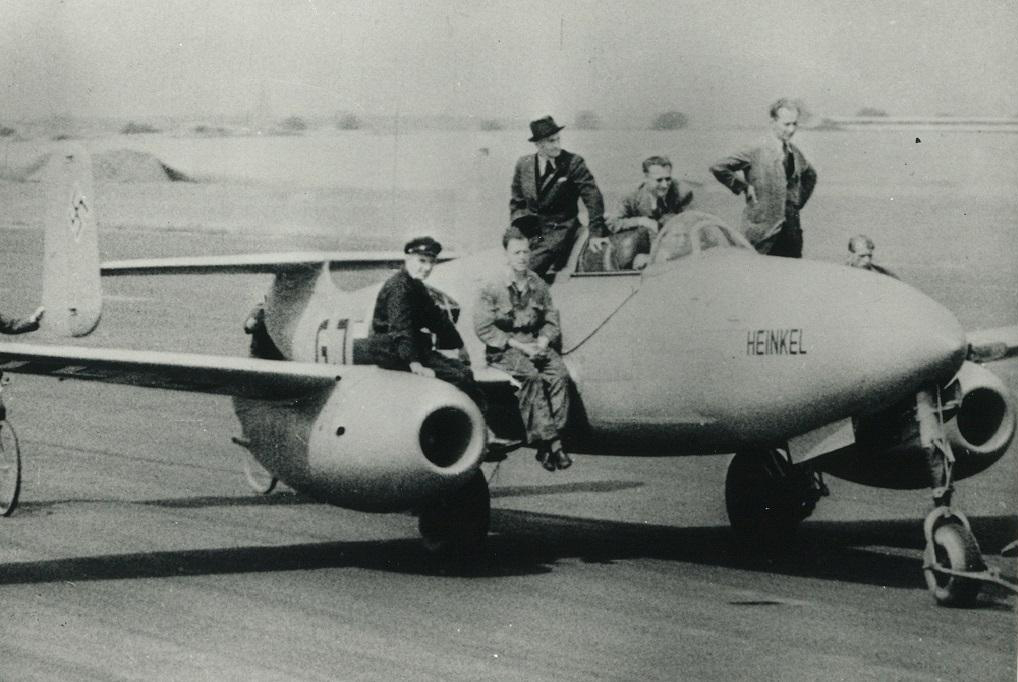

5. Heinkel He 280

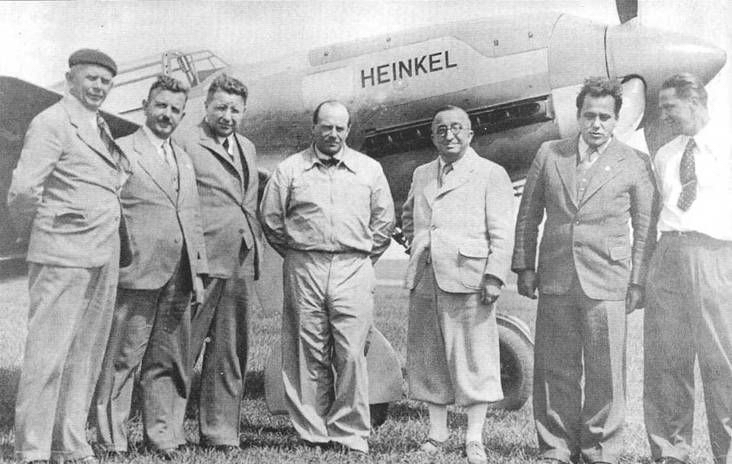

The Heinkel team look pretty pleased with their revolutionary new aircraft as it is towed in after an early test flight. Their jolly mood was not to last.

Were it not for woeful official indifference, it is likely the Heinkel He 280 would have proved a significant problem for the Allies. As it turned out, the world’s first jet fighter saw neither production nor service.

Ernst Heinkel’s company were way ahead of the game in this field having flown the world’s first jet powered aircraft a few days before the war even started. When demonstrated in November 1939, the revolutionary new aircraft failed to impress Reichsluftministerium (RLM) grandees Ernst Udet (head of the Technological department) and Erhard Milch (Minister of Aircraft Production and Supply), a lack of response that infuriated Ernst Heinkel. It was also a premonition of things to come. Without the enthusiasm of the RLM, Heinkel was compelled to develop the new technology as a private venture. The Heinkel He 280 was the result, a purpose built fighter, powered by two of Heinkel’s own HeS 8 turbojets. Flown first as a glider, the new aircraft made its initial powered flight on the 30th March 1941, despite the lack of official support this was still over a year before the Me 262 and two years before the Gloster Meteor.

The He 280 first flew as a glider, here it is being towed aloft with fairings where the jet engines are to be fitted.

Demonstrated to Ernst Udet on the 5th of April, the He 280 again failed to make much of an impression. Despite being capable of over 500 mph in level flight, official interest was piqued only by the jet engine’s ability to run on relatively unrefined low octane fuel oil – even at that stage of the war, there was an acute awareness that Germany’s fuel supply was critical to its success. Heinkel however was denied funding again but continued to develop the aircraft despite the underwhelming response of officialdom. Eventually, in December 1943, now sporting two improved examples of the HeS-8 engine, the He 280 was once again demonstrated to RLM officials (not the unfortunate Ernst Udet though, he had shot himself back in November 1941). This time, to really make his point, Ernst Heinkel had arranged a mock dogfight with a Focke-Wulf Fw 190, arguably the best piston-engine fighter in service in the world at the time. The He 280’s massive speed advantage allowed it to trounce the Fw 190 and at last the RLM realised what an incredible machine they had on their hands and ordered 20 pre-production aircraft to be followed by an order for 300 more.

Early test flight under power, the engine cowlings have been left off to minimise the danger of leaking fuel pooling within and catching fire.

Unfortunately, despite their tardy enthusiasm for the project, the RLM had ordered Heinkel to stop work on the HeS 8 back in 1942 to concentrate on the more ambitious HeS 011, an engine that failed to make it into production before the end of the war. In the absence of an engine, Heinkel had been desperately seeking alternatives: the first prototype was re-engined with four Argus pulse jets, the same as fitted to the V-1 ‘doodlebug’ but crashed on its first test flight after the controls iced up. This incident led to the first genuine use of an ejection seat for a pilot to escape a stricken aircraft, the He 280 being the first aircraft to be fitted with such a device. Test pilot Helmut Schenk earned this dubious honour on the 13th January 1942. The other two alternative powerplants were the BMW 003 and the Junkers Jumo 004. The BMW was having developmental issues of its own so the He 280 was fitted with a pair of Jumo 004s. In this form it first flew on 16th March 1943. Despite the greater weight and size of the Junkers engine, the He 280 flew perfectly well in this form but it was too late, the Messerschmitt Me 262 fitted with the same engine was faster and generally more efficient. Two weeks later Erhard Milch cancelled the He 280 programme and Heinkel was instructed to concentrate on bombers.

The third prototype. This aircraft was captured intact in May 1945 at Heinkel’s factory complex at Wien-Schwechat, Austria. Its subsequent fate is unknown.

Though it needed work, the He 280 may have been the greatest overall missed opportunity in German aviation. The HeS 8 engine was underdeveloped when it first flew but its problems were overcome, even without official support or funding, only for it to be cancelled anyway. Had the He 280 programme (both engine and airframe) received official backing in 1941 it is not unlikely that the Luftwaffe could have been fielding a jet fighter, capable of over 500 mph and therefore effectively immune from interception by Allied fighters, by early 1943. This predates the advent of the P-51 Mustang as the premier long range escort fighter of the war and it is not hard to imagine its presence being rendered largely irrelevant by a force of un-interceptable jet fighters. Luckily for the world the Nazis failed to see the potential of this aircraft until it was too late for Germany as a whole and the Heinkel He 280 in particular. Meanwhile the Me 262 made history as the World’s first combat jet and Ernst Heinkel remained bitter about the whole sorry debacle for the rest of his life.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Inexplicable official indifference

Engine unavailable

4. Martin-Baker MB.3/MB.5

Bearing a superficial resemblance to the P-51D Mustang, the MB.5 was 500 hp more powerful, faster, better armed, and (surprisingly) possessed a superior range on internal fuel.

I’m cheating a bit here, including two separate designs as one entry but Martin-Baker’s final two fighters were inextricably linked, one being a development of the other, both were outstanding and neither made it to production. Martin-Baker was (and indeed still is) an aviation component manufacture who produced, seemingly out of the blue, two of the best fighter aircraft ever flown anywhere.

The MB.3 was a brutish, powerful aircraft. Note the six cannon fitted in the wing.

The MB.3’s flying career was short: the engine failed on its tenth flight, killing test pilot Val Baker and destroying the aircraft.

A sombre James Martin in front of his masterpiece.

Despite the crash it was apparent that the MB.3 was worthy of further development. Baker proposed a Rolls-Royce Griffon powered version, the MB.4 but a more thorough redesign was favoured by the Air Ministry and the MB.5 was the result. The best British piston-engined fighter ever flown, the MB.5 was well-armed (though with the less impressive total of four rather than six cannon), very fast, and as easy to maintain as its predecessor. Flight trials proved it be truly exceptional, with a top speed of 460mph, brisk acceleration and docile handling. Its cockpit layout set a gold standard that Boscombe Down recommended should be followed by all piston-engined fighters.

The only thing the MB.5 lacked was good timing, it first flew two weeks before the Allied Invasion of Normandy. Appearing at the birth of the jet age, with readily available Spitfires and Tempests being produced in quantity, both of which were themselves excellent fighters, there was never a particularly compelling case for producing the slightly better MB.5. There is also a suggestion that the MB.5 never received a production order because on the occasion it was being demonstrated to assorted dignitaries, including Winston Churchill, the engine failed. If this is true, it must rank as the most pathetic reason for non-procurement of an outstanding aircraft in aviation history.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Inexplicable official indifference,

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already,

Bad timing

The best British piston-engined fighter taxies off to an uncertain future

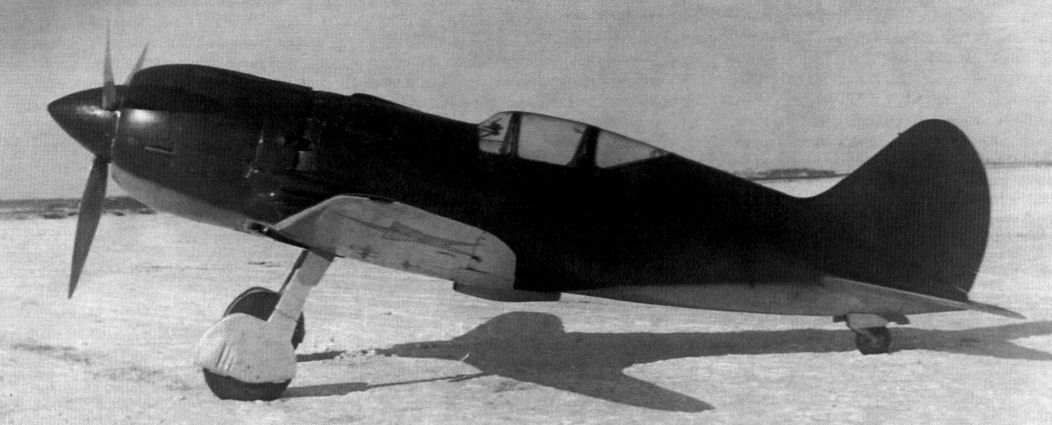

3. Polikarpov I-185

Photos of the I-185 are rare, in flight shots apparently unknown. This is the closest you’ll get, at least the engine is running. Note that the chocks are tied to the undercarriage and weights to the tail.

A direct descendant of Polikarpov’s revolutionary I-16, the I-185 Nikolai Polikarpov’s I-185 was an excellent aircraft stymied by engine trouble, politics, timing, and outright bad luck. Uniquely amongst this selection, it was also sent to the front and actually flew on operations. It should have been the finest fighter the USSR fielded during the Great Patriotic war with 2000hp on tap, slightly smaller than a Grumman Bearcat but weighing 1900 lb less in normal loaded condition, faster than the contemporary Bf 109F at all altitudes up to 20,000 feet, its handling was immeasurably better and it was recommended for immediate production in the Autumn of 1942. Yet it ended up merely an also-ran. The problems began way back in 1937 when Polikarpov’s incredibly successful I-16 was fighting in the Spanish Civil war. Republican forces captured a Messerschmitt Bf 109B which was evaluated thoroughly by a team of Soviet experts. The consensus was that the 109 was inferior in virtually every regard to the latest I-16 Type 10. Whilst this was true, it was unfortunate that the Soviets failed to envisage the incredible rate of development of the 109; had they captured one of the considerably better 109Es that were fielded in Spain in the latter stages of the Civil war it might have encouraged greater urgency in developing a successor to the I-16. As it was, work on an I-16 replacement proceeded in a somewhat leisurely fashion and aimed for rather conservative performance improvement.

The poster for ‘Valeri Chkalov’ (released as ‘Red Flyer’ in the UK and ‘Wings of Victory’ in the US).

The fighter that emerged was the named I-180 and looked very much like stretched I-16. Development seemed to be going well until December 1938 when the test pilot Valeri Chkalov was killed in the prototype. Unfortunately for Polikarpov, Chkalov was a bona fide national hero of immense popularity. Whilst his body lay in state and was visited by all the principal military and civil dignitaries, the NKVD started arresting members of the design team on suspicion of sabotage. It is said that only the personal intervention of Stalin prevented Polikarpov himself being packed off to the gulag. Work continued on the new fighter, though the programme was somewhat under a cloud. Meanwhile Chkalov’s home town was renamed in his honour and in 1941 an eponymous biopic of his life was made.

After Chkalov’s death a major redesign was implemented and the resulting I-180S looked a lot less like the I-16 which had spawned it. Unfortunately for the new fighter two prototypes were lost in spins in quick succession resulting in the death of another test pilot, Tomass Susy. Although 10 pre-series examples were built during 1940 the performance of the aircraft was tacitly admitted to be lagging behind world-class and a further redesign was undertaken. The resulting aircraft was the I-185 and it was intended for either the M-90 or M-71 engine offering nearly double the power of the M-88 fitted to the I-180S. Both engines were troubled but the M-90 particularly so and it was abandoned. The M-71 eventually achieved sufficient reliability to power the first I-185 to fly in February 1942. The aircraft flew beautifully and the M-71 was getting over its teething troubles, when it functioned properly the performance was spectacular (a speed of 426 mph was ultimately to be recorded) and the future finally should have looked rosy for Polikarpov’s purposeful fighter.

Although it was not compulsory to photograph the I-185 in the snow, it did serve to make it look more Soviet Union-y.

However, by this time everything had been thrown into chaos by the Germans having invaded and beginning their headlong rush towards Moscow. The Soviets needed lots of fighters immediately and didn’t have the luxury of waiting for promising prototypes. Unpopular but available fighters were produced in their thousands and gradual evolution rather than completely new types ultimately yielded the two major Soviet fighter series from Lavochkin and Yakovlev. Yet the I-185 was so good that it refused to die. In November 1942, the three prototypes were sent to the front to be evaluated under operational conditions. The report was unambiguously favourable: “The I-185 outclasses both Soviet and foreign aircraft in level speed. It performs aerobatic manoeuvres easily, rapidly and vigorously. The I-185 is the best current fighter from the point of control simplicity, speed, manoeuvrability (especially in climb), armament and survivability.” Plans were begun to start production forthwith and a ‘production standard’ aircraft was completed. Unfortunately the engine failed and it crashed. Development continued with the original three prototypes, one of which crashed and killed its pilot after another engine failure in January 1943. The M-71 was rapidly being considered a dead end.

Plans to produce the I-185 with the reliable but lower-powered M-82 were eventually abandoned as the M-82 was required for the inferior (but good enough) La-5 that, crucially, was already in production and the I-185 programme was formally cancelled in April 1943, finally depriving the Soviet Union of its finest piston-engined fighter. A little over a year later Nikolai Polikarpov was dead and his design bureau was eventually absorbed into Sukhoi.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Engine unavailable,

Death of designer (and/or other significant personage),

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already,

Teething troubles

2. Beechcraft XA-38 Grizzly

“Does my gun look big in this?” The XA-38 shows off its tank-derived main armament.

Founded in 1932, Beechcraft are still going strong, their Bonanza has been in continuous production longer than any other aircraft (72 years at the time of writing) and around 17,000 have so far been built. Rather less successful was Beechcraft’s sole foray into the world of combat aircraft: the Grizzly, a mere two examples of which were built.

But what an aircraft: its primary armament was a 75-mm gun in the nose, the same as fitted to the Sherman tank. As a dedicated ground attack aircraft, its enormous gun was intended for use against hardened targets such as pillboxes and tanks. Two forward firing 50-calibre machine guns were used to aim the main weapon and tests had proved the armament particularly effective. Most dedicated ground attack aircraft of the Second World War were relatively slow and vulnerable to fighter attack but the Grizzly was fast: despite being the size of a medium bomber it was capable of 376 mph at 5000 feet, 10 mph faster than a P-47D at the same altitude. It was also extremely well defended with both dorsal and ventral turrets each mounting two 50-calibre machine guns to deal with any fighter aircraft it might not be able to outrun, which were few indeed at the low altitudes it was designed for.

Beech were justifiably proud of the XA-38 ‘Affectionately called “Grizzly” by the pilots who flew it’. It was probably an aircraft better suited to the Korean and Vietnam conflicts than those the USAF actually took into combat.

Despite its high performance and crazy armament its serviceability also drew praise, which was highly unusual for prototypes of a brand new aircraft. The XA-38 was one of those extremely rare military aircraft that met or exceeded every parameter of their design specification and was as close to perfect on a first attempt as is ever likely to happen. An outstanding career would reasonably have been expected for it. Unfortunately for Beechcraft the Grizzly’s fantastic performance was largely a result of its Wright R-3350 ‘Duplex-Cyclone’ engines, the same engines used by the B-29 Superfortress. Even the awe-inspiring industrial might of the US had limits and there weren’t enough R-3350s to go round, the B-29 had priority and the XA-38 was consigned to history – literally: one of the Grizzly prototypes was intended for preservation at the USAF museum. Alas, somehow it was lost and its ultimate fate remains a mystery. The other example was scrapped.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

At least one of the XA-38s survived long enough to be photographed in colour.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Engine unavailable

1. Heinkel He 100

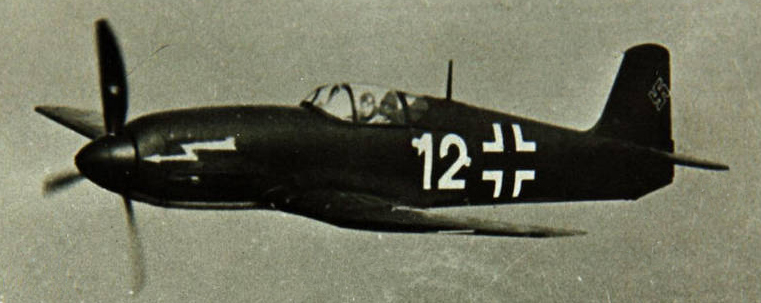

Heinkel’s finest masquerades as a fully operational fighter. The He 100’s greatest achievement was arguably persuading the world that it was in full-scale service, which is a shame as it was potentially the best fighter available to the Luftwaffe.

In 1938 Ernst Udet, taking time out from his strenuous drinking and womanising schedule, flew the second prototype of a new German fighter to set a world record speed of 394 mph over a 100 km closed circuit. The prototype was the He 100, Heinkel’s rival to the Messerschmitt 109, and it really should have been built in quantity. It was a superior aircraft to the 109 and available years earlier than the Focke-Wulf 190, which was also inferior in some respects. The reasons for its Luftwaffe rejection remain obscure, which only add to its mystique.

Back in 1936 Heinkel’s alternative to Messerschmitt’s all-conquering 109 was the He 112. It was an elegant aircraft with elliptical wings and decent performance, however it wasn’t quite as good as the Messerschmitt and it was time-consuming to build. Although a few were built for Romania and Spain, a major production order from the Luftwaffe was not forthcoming. Heinkel’s designer, the immensely talented Walter Günter realised the He 112 had reached the limits of its design potential and that a completely new aircraft would be required. This was to be the He 113, and it promised to deliver the fighter market back to Heinkel. Not only was the new aircraft more aerodynamic than the He 112 (and the Messerschmitt), thanks to clever design it also far simpler to build, the wings alone taking 1500 fewer hours to construct. Ultimately the He 113 would be designated the He 100 at the request of Ernst Heinkel, who feared the unlucky connotations of the number 13 would rub off on his exciting new fighter, as it turned out it seems his superstition was well-founded. Despite the number change, the Heinkel fighter was very unlucky indeed. An unfortunate early example of this being the death of Walter Günter in a car crash in 1938, his position being taken over by his twin brother Siegfried (an unusual hiring policy, even by the standards of Nazi era Germany).

The first prototype He 100 V1 flew on 22 January 1938, only a week after its promised delivery date. The aircraft proved to be outstandingly fast. Later the fin area was increased to deal with a lack of directional stability. The wing loading was high and landing speed was initially prohibitively fast.

Initially all seemed bright for the He 100. The prototypes were very very fast and their low drag airframes also made for an impressive range. The only really negative point was the cooling system which was a very aerodynamic but highly complex evaporative cooling system that required 22 separate electric pumps, each with its own warning light in the cockpit, to circulate the coolant around the airframe. When Udet flew the Heinkel on its successful record attempt several of the pumps failed but Udet ignored the warning lights flicking on in the cockpit because he didn’t know what they meant. True air aces are unconcerned with trifles like mechanical failure. The cooling system was constantly unreliable so it was ditched for the pre-production aircraft and replaced with a conventional radiator. In this form, the Heinkel He 100 was probably the best fighter in the world and ready for a Luftwaffe order, which Heinkel was so confident of getting that he tooled up and started production of his own accord. But of course the order never came.

Ernst Udet and Ernst Heinkel (4th and 5th from left respectively) with the rest of the Heinkel record-breaking team, all of whom appear to be baddies from Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin.

The reason why the He 100 never entered production depends on who you believe. It is suggested that the Nazis wished to ‘rationalise’ aircraft production by making Messerschmitt solely concentrate on fighters and Heinkel responsible for bombers. Meanwhile Heinkel maintained that it was political favouritism of Willy Messerschmitt that stymied the He 100, which seems unlikely as Heinkel too was well thought of in official circles. The official RLM line was that Daimler Benz DB 601s were in such short supply that the only aircraft sanctioned to use this engine was the Bf 109. The latter is probably true but it is impossible to say for sure.

Contemporary postcard (with rather heavy postmark) depicting a Heinkel He 100 ‘escorting’ an He 111 on a mission. It was all fiction.

The cancellation of this aircraft can be seen to have had a detrimental effect on the Luftwaffe’s fighter arm at the critical time of the Battle of Britain. Much like the Fw 187 detailed earlier, the He 100 offered a considerably greater range than the Bf 109, equating to a combat radius of some 900 – 1000 km compared with the 109’s 600 km. Given that the BF 109 could only operate over London for ten minutes, a single-seat, single-engine escort fighter with much greater combat persistence that also happened to be the best fighter in the world, would have been a ludicrously useful asset.

Oft-reproduced image of one of the pre-production aircraft in spurious markings.

The story does not end there though as the Japanese were scouting around for a decent fighter in the late thirties and their interest was aroused by the new Heinkel. They purchased three complete He 100s as well as a license for production plus a set of plans and jigs for a total of three million Reichsmarks. The three aircraft arrived in Japan in May 1940 and the Navy was so impressed that they planned to put the plane into production as soon as possible as their land-based interceptor. Hitachi won the contract for the aircraft and started building a factory in Chiba for its production. However, the jigs and plans never arrived, for reasons that remain unclear, and the Heinkel was never built in Japan. The design is said to have influenced the Kawasaki Ki-61 though, which notably used the same engine. The Soviet Union also bought six prototypes of the He 100, as they were interested in its evaporative cooling system – ultimately leading to the Soviets wisely rejecting this cooling method. The design is said to have influenced that of the LaGG-3 but given the generally poor performance of that aircraft and the fact that it resembled the Heinkel in no perceptible regard this seems unlikely.

More lies: a squadron of Heinkels lines up for the camera. It’s not even really in colour.

Like the similarly promising Fw 187, the remaining pre-production aircraft were then heavily photographed for propaganda purposes to make it look like they were in full-scale service. What is less clear is who exactly this propaganda was intended for, the German public or the Allies? If the latter, it was extremely successful: despite never entering Luftwaffe service the Heinkel regularly featured in combat reports filed by British and US pilots throughout the war.

REASONS FOR CANCELLATION:

Engine unavailable,

Inexplicable official indifference,

Death of designer (and/or other significant personage),

Other aircraft perceived to be good enough already,

Politics(?)

We can only bring your articles like this with your support. Our site is absolutely free and we have no advertisements (any you do see, are from WordPress). If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here.

See also

- Aircraft design contest 2019 launched

- 10 exotic cancelled fighter planes from countries you didn’t expect

- An idiot’s guide to aircraft design, part 5: Stealth comes at a cost

- Interview with Soviet air force Su-15 ‘Flagon’ fighter pilot: Defending the USSR

- An idiot’s guide to aircraft design – Part 2: How to build an aircraft with great endurance

- An idiot’s guide to aircraft design – Part 1: How to build the fastest-climbing fighter

- An idiot’s guide to aircraft design: Introduction

- Vote on the Top 10 aircraft of the Royal Navy

- Flying & Fighting in the Saab Viggen: Cold War Thunder

Regarding the Beech XA38, a further reason for non production could have been the development of a 75mm gun version of the B25 Mitchell. Soon enough the large calibre air to ground gun was superseded by the air to ground rocket of various sizes sometimes with 5in shell warhead. Without recoil, the rockets could be carried under the wing on fighter bombers which were better suited to the low level work.

Regarding the Heinkel 100D, this fighter used a an overly complicated and vulnerable cooling system where coolant was routed from the DB601 engine to cavities in the wings and fuselage for cooling. If any of these areas were punctured, even by a rifle calibre machine gun bullet, the resulting loss of coolant would have resulted in the pilot having to abandon the aircraft. Also, the wing area was small resulting in high wing loading making the aircrafts controls heavy and awkward.

No. 11 The CAC CA15

developed too late and superceded by jets

There is 1 aircraft missing from this the USA smuggled it out out of a newly libirated Germany of it was stored in the UK for a week we now know this aircraft as the B2 stealth bomber