RC-135 pilot interview: Cold War Spyflights

The RC-135 has been quietly snooping and changing history for almost 60 years. Robert Hopkins flew the RC’ in the heat of the Cold War, braving intercepting MiG-31s and other threats to eavesdrop on the US’ potential enemies and hoover up vital intelligence for Presidents and generals. We met him to find out more.

What is the best thing about the RC-135?

“That’s a tossup: It has one of the best mission in the world, and it is crewed by some of the best people in the world. They naturally gravitate toward one another.”

The RC-135 has been quietly snooping and changing history for almost 60 years. Robert Hopkins flew the RC’ in the heat of the Cold War, braving intercepting MiG-31s and other threats to eavesdrop on the US’ potential enemies and hoover up vital intelligence for Presidents and generals. We met him to find out more.

What is the best thing about the RC-135?

“That’s a tossup: It has one of the best mission in the world, and it is crewed by some of the best people in the world. They naturally gravitate toward one another.”

What were your first impressions of the aircraft?

“I saw RC-135s at Offutt AFB during the early 1970s while I was in high school in nearby Bellevue, NE. My favorite was the COMBAT SENT with the rabbit ears and cheeks. It was very “bad assed” looking, which was all that mattered to an impressionable teenager.

The day I arrived at Eielson AFB in 1987 as a new copilot I saw RC-135S 61-2663 on the ramp, and was struck with an extraordinary sense of responsibility. I would be part of a team that flies an amazing technical intelligence platform on short-notice launches from one of the world’s most inhospitable locations on a mission of such national importance that its results are often briefed at the highest levels of government. I also fell in love with the black wing, which remains on the CBs to this day as a symbol of the airplane’s importance and legacy.”

Tell me something I don’t know about the type?

“Despite the long association of the 55th at Offutt AFB and the RC-135, the early years of RC-135 operations were developed by other units.

The first ‘135 reconnaissance mission was undertaken on 30th October 1961 by a rapidly modified JKC-135A SPEED LIGHT-ALPHA to monitor the Soviet “Tsar Bomba” atmospheric test at Novaya Zemlya. This was flown by SAC tanker crews (there were subsequent missions) drawn from air refueling squadrons.

The next ‘135 reconnaissance missions were flown in January 1962 by a KC-135A known as NANCY RAE, with crews from Wright-Patterson AFB operating from Shemya AFB, AK. This was later redesignated as a JKC-135A and then WANDA BELLE and finally the RIVET BALL RC-135S. In December 1962 this was joined at Eielson AFB by three KC-135A-II OFFICE BOY COMINT/ELINT platforms.

The three SPEED LIGHT airplanes were based at Offutt AFB beginning in 1963 and assigned to the 34th AREFS, but at this time the 55th SRW still flew RB-47s and was based at Forbes AFB, KS. The 55th did not receive its first RC-135s until it relocated to Offutt in 1966 and acquired the BIG TEAM RC-135B/.

The SAC reconnaissance community is fairly small, and crews served in both units (as did I). It remained a matter of some pride, however, for the 4157th SW (later 6th SW/SRW) that the original RC-135 recon jets (especially those configured for aerial refueling like the RC-135S and KC-135A-II) were not 55th SRW assets. All in good spirits, unless fueled by “spirits.”

Why is it important?

“The RC-135 fleet (and its predecessors) entered service as a strategic peacetime asset, and flew missions as part of the Peacetime Aerial Reconnaissance Program (PARPRO). The airplanes served two roles: detection of long-term preparations for any impending attack on the US and its allies, and collection of intelligence data essential to allowing Strategic Air Command (SAC) and its successor to fulfill its Single Integrated Operations Plan (SIOP), the heart of “Deterrence”.

Since DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM in 1990/91, however, the RIVET JOINT mission has faded from view in light of the shift in focus toward “warfighter support” in the seemingly endless conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, as well as counter-narcotics operations in the Caribbean and Central America, and events in North Korea and the South China Seas. It’s become increasingly difficult to separate these two peacetime and wartime functions, especially as new technologies alter the environment and platforms.”

Any tips for the new RAF RC-135 crews?

“Learn everything there is to know about your airplane and its mission, no matter what position you’re assigned. What you do is vitally important, and you need to do it very well and without hesitation. Although it may seem that your mission supports combat operations, it is equally essential in preventing unanticipated conflict—you are at the front line of peace. Never lose sight of this dual purpose.”

Worst behaviour you saw on an RC-135 mission or base?

What were your first impressions of the aircraft?

“I saw RC-135s at Offutt AFB during the early 1970s while I was in high school in nearby Bellevue, NE. My favorite was the COMBAT SENT with the rabbit ears and cheeks. It was very “bad assed” looking, which was all that mattered to an impressionable teenager.

The day I arrived at Eielson AFB in 1987 as a new copilot I saw RC-135S 61-2663 on the ramp, and was struck with an extraordinary sense of responsibility. I would be part of a team that flies an amazing technical intelligence platform on short-notice launches from one of the world’s most inhospitable locations on a mission of such national importance that its results are often briefed at the highest levels of government. I also fell in love with the black wing, which remains on the CBs to this day as a symbol of the airplane’s importance and legacy.”

Tell me something I don’t know about the type?

“Despite the long association of the 55th at Offutt AFB and the RC-135, the early years of RC-135 operations were developed by other units.

The first ‘135 reconnaissance mission was undertaken on 30th October 1961 by a rapidly modified JKC-135A SPEED LIGHT-ALPHA to monitor the Soviet “Tsar Bomba” atmospheric test at Novaya Zemlya. This was flown by SAC tanker crews (there were subsequent missions) drawn from air refueling squadrons.

The next ‘135 reconnaissance missions were flown in January 1962 by a KC-135A known as NANCY RAE, with crews from Wright-Patterson AFB operating from Shemya AFB, AK. This was later redesignated as a JKC-135A and then WANDA BELLE and finally the RIVET BALL RC-135S. In December 1962 this was joined at Eielson AFB by three KC-135A-II OFFICE BOY COMINT/ELINT platforms.

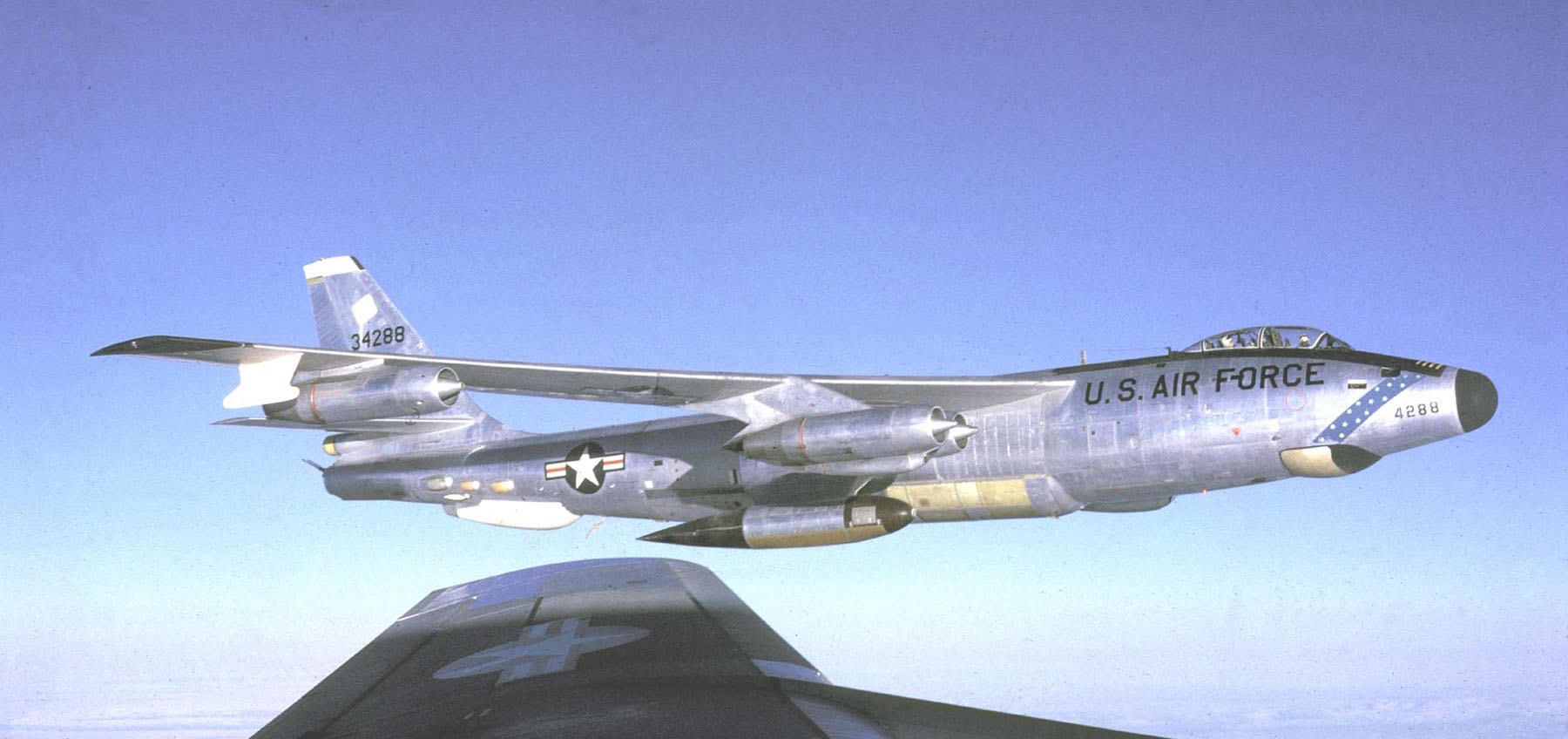

The three SPEED LIGHT airplanes were based at Offutt AFB beginning in 1963 and assigned to the 34th AREFS, but at this time the 55th SRW still flew RB-47s and was based at Forbes AFB, KS. The 55th did not receive its first RC-135s until it relocated to Offutt in 1966 and acquired the BIG TEAM RC-135B/.

The SAC reconnaissance community is fairly small, and crews served in both units (as did I). It remained a matter of some pride, however, for the 4157th SW (later 6th SW/SRW) that the original RC-135 recon jets (especially those configured for aerial refueling like the RC-135S and KC-135A-II) were not 55th SRW assets. All in good spirits, unless fueled by “spirits.”

Why is it important?

“The RC-135 fleet (and its predecessors) entered service as a strategic peacetime asset, and flew missions as part of the Peacetime Aerial Reconnaissance Program (PARPRO). The airplanes served two roles: detection of long-term preparations for any impending attack on the US and its allies, and collection of intelligence data essential to allowing Strategic Air Command (SAC) and its successor to fulfill its Single Integrated Operations Plan (SIOP), the heart of “Deterrence”.

Since DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM in 1990/91, however, the RIVET JOINT mission has faded from view in light of the shift in focus toward “warfighter support” in the seemingly endless conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, as well as counter-narcotics operations in the Caribbean and Central America, and events in North Korea and the South China Seas. It’s become increasingly difficult to separate these two peacetime and wartime functions, especially as new technologies alter the environment and platforms.”

Any tips for the new RAF RC-135 crews?

“Learn everything there is to know about your airplane and its mission, no matter what position you’re assigned. What you do is vitally important, and you need to do it very well and without hesitation. Although it may seem that your mission supports combat operations, it is equally essential in preventing unanticipated conflict—you are at the front line of peace. Never lose sight of this dual purpose.”

Worst behaviour you saw on an RC-135 mission or base?

Hopkins’ first combat flight.

Cold War spy flights What were US recce aircraft doing in the Cold War?

“As I noted in an earlier answer, they had two primary roles: early long-term warning of an impending attack by the USSR and its allies and to acquire intelligence needed to fulfill the deterrent strike mission. Most of this was undertaken by SAC to meet its intelligence requirements, but the US Navy flew a fair number as well, as did USAFE and PACAF in “electric” C-130s. Other nations did too, with both Britain and Sweden building modest but successful programs early on, followed by other North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries. We shouldn’t forget the CIA missions, including the 24 total U-2 overflights of the USSR (small by comparison to the 156 RB-47 overflights in 1956 alone).” Was it dangerous? What mistakes were made?

“These were very dangerous missions, not only because the USSR, PRC, and North Korea were willing and able to attack them and shoot them down, but because the airplanes were not always reliable or were too old. Sending RB-29s or RB-50s on missions where they were subject to attack by MiG-15s or MiG-17s was a horrible mismatch. Airplanes also struggled with breaking or other maintenance issues.

No doubt there were ill-considered decisions to undertake specific missions, and the subject of overflights remains highly contentious. In general, however, decision makers in the West acted out of genuine desperation to acquire intelligence they considered critical to the survival of the West in the face of what they saw as an existential communist threat to the liberal capitalist world order.”

Was it dangerous? What mistakes were made?

“These were very dangerous missions, not only because the USSR, PRC, and North Korea were willing and able to attack them and shoot them down, but because the airplanes were not always reliable or were too old. Sending RB-29s or RB-50s on missions where they were subject to attack by MiG-15s or MiG-17s was a horrible mismatch. Airplanes also struggled with breaking or other maintenance issues.

No doubt there were ill-considered decisions to undertake specific missions, and the subject of overflights remains highly contentious. In general, however, decision makers in the West acted out of genuine desperation to acquire intelligence they considered critical to the survival of the West in the face of what they saw as an existential communist threat to the liberal capitalist world order.”

A typical day at Shemya.

Hopkins’ first KC-135 flight.

RCX at Semya.

“All” is such a big basket. In general, they were necessary to reassure Western leaders that the threat from the secretive USSR was only hypothetical. In that case they were both ethical and effective. Conversely, many of the flights led to increased demands for atomic weapons and delivery systems to destroy the—literally—thousands of new targets discovered. U-2s alone added 20,000 designated ground zeros (DGZs) to the potential target list. This led directly to inflated demands for strategic weapons, which Eisenhower correctly criticized (but could not prevent) in his remarks about the military industrial complex using taxpayers’ money to support corporate profits based on unnecessary defense acquisitions driven in large part by intelligence collected from aerial reconnaissance missions.”

What was Britain’s role in Cold War spy flights?

“Britain had a unique place. It served as a base for US peripheral missions from the late 1940s until today. In the early 1950s, RAF crews flew SAC RB-45s seconded to RAF Sculthorpe on nine overflights of the USSR under the JU JITSU and JU JITSU II missions, and allowed one SAC RB-47E overflight of Murmansk in 1954. Britain originally agreed but later rejected to host CIA U-2 operations in 1956, which were relocated to Wiesbaden, FRG, and RAF pilots flew two U-2 overflights of the USSR. The loss of the RB-47H on 1 July 1960 changed the way Britain did business with the US. All future missions were subject to approval by the Prime Minister.”

“All” is such a big basket. In general, they were necessary to reassure Western leaders that the threat from the secretive USSR was only hypothetical. In that case they were both ethical and effective. Conversely, many of the flights led to increased demands for atomic weapons and delivery systems to destroy the—literally—thousands of new targets discovered. U-2s alone added 20,000 designated ground zeros (DGZs) to the potential target list. This led directly to inflated demands for strategic weapons, which Eisenhower correctly criticized (but could not prevent) in his remarks about the military industrial complex using taxpayers’ money to support corporate profits based on unnecessary defense acquisitions driven in large part by intelligence collected from aerial reconnaissance missions.”

What was Britain’s role in Cold War spy flights?

“Britain had a unique place. It served as a base for US peripheral missions from the late 1940s until today. In the early 1950s, RAF crews flew SAC RB-45s seconded to RAF Sculthorpe on nine overflights of the USSR under the JU JITSU and JU JITSU II missions, and allowed one SAC RB-47E overflight of Murmansk in 1954. Britain originally agreed but later rejected to host CIA U-2 operations in 1956, which were relocated to Wiesbaden, FRG, and RAF pilots flew two U-2 overflights of the USSR. The loss of the RB-47H on 1 July 1960 changed the way Britain did business with the US. All future missions were subject to approval by the Prime Minister.”

“Britain had its own aerial reconnaissance capability, known as “radio proving flights” for ELINT and COMINT, and flew high-altitude Canberra PR.9s on peripheral PHOTINT missions. I agree with U-2 expert Chris Pocock and others that the alleged 1953 UK ROBIN overflight of Kapustin Yar is a myth.

In recent years RAF’s 51 Squadron has fulfilled the strategic reconnaissance role, and suffered a terrible loss of life in Afghanistan. I understand the concerns about replacing the aging Nimrod MR.1 ELINT platform with a similarly ancient RC-135 that has less ELINT capability and more COMINT capability.”

“Britain had its own aerial reconnaissance capability, known as “radio proving flights” for ELINT and COMINT, and flew high-altitude Canberra PR.9s on peripheral PHOTINT missions. I agree with U-2 expert Chris Pocock and others that the alleged 1953 UK ROBIN overflight of Kapustin Yar is a myth.

In recent years RAF’s 51 Squadron has fulfilled the strategic reconnaissance role, and suffered a terrible loss of life in Afghanistan. I understand the concerns about replacing the aging Nimrod MR.1 ELINT platform with a similarly ancient RC-135 that has less ELINT capability and more COMINT capability.”

Canberra PR.9

US Navy PB4Y Privateer

US Navy EC-121

What is the RC-135 and what do they do?

Hopkins’ last RC-135 flight.

“RCs have three distinct mission:

The RIVET JOINT V/Ws have an ELINT/COMINT mission,

(ELINT or Electronic intelligence is intelligence-gathering by electronic sensors. The purpose is often to assess the capabilities of a target, such as the location and nature of a radar)

the COMBAT SENT Us have a specialised ELINT mission

(According to the USAF website, “The RC-135U Combat Sent provides strategic electronic reconnaissance information to the president, secretary of defense, Department of Defense leaders, and theater commanders. Locating and identifying foreign military land, naval and airborne radar signals, the Combat Sent collects and minutely examines each system, providing strategic analysis for warfighters. Collected data is also stored for further analysis by the joint warfighting and intelligence communities. The Combat Sent deploys worldwide and is employed in peacetime and contingency operations.”)

and the COBRA BALL Ss have a MASINT/TELINT mission.”

(Measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) serves to detect, track, identify or describe the signatures (distinctive characteristics) of fixed or dynamic target sources. This often includes radar, acoustic intelligence and nuclear chemical & biological intelligence.)

What should I have asked you? “My favorite intercept took place on 3 October 1988 while flying RC-135S 61-2662 with Major “Mad Jack” Elliott off Kamchatka. While proceeding northbound in our orbit I noticed a glint well off to the northeast. I followed it a bit, and figured it was an Il-76 on a cargo mission from Anadyr to Petropavlovsk. It disappeared and we continued our orbit. We had a quick visit by a MiG-31 ‘Foxhound’ from “Pete”, and then it was all quiet again on a sweet sunny afternoon.

Shortly thereafter (again while heading north) I was stunned as a Tu-16 ‘Badger’ pulled up on our right wingtip in the tightest formation you could imagine. I waved to the pilot and he waved back. I broadcast the required HARVARD message (indicating that we were intercepted in international airspace) and then resumed our mission business. The Tu-16 stayed parked on our wingtip for the two hours or so. It was a beautiful thing to watch.

By this time we still had a lengthy launch window to cover and were running low on fuel, so we left the orbit and sensitive area to head to our tanker. The ‘Badger’ remained tucked into position. As we approached the tanker, their boom operator squeaked over the radio something like:

“COBRA 55 do you know you’re not alone?”

“Roger, we know.”

“What should I do?”

“Well, if he wants gas, give it to him.”

As we moved forward to the pre-contact position I noticed there was now a person with a huge movie camera in the plexiglas dome atop the fuselage aft of the cockpit. He filmed the entire air refueling procedure in close-up detail. After we had received our fuel I motioned for the BADGER to move into the recontact position (visions of a cover photo for Aviation Week danced in my head), but he declined. The pilot waved goodbye and headed south. I sent out our BROTHER message that our escort had departed and that was that!”

“My favorite intercept took place on 3 October 1988 while flying RC-135S 61-2662 with Major “Mad Jack” Elliott off Kamchatka. While proceeding northbound in our orbit I noticed a glint well off to the northeast. I followed it a bit, and figured it was an Il-76 on a cargo mission from Anadyr to Petropavlovsk. It disappeared and we continued our orbit. We had a quick visit by a MiG-31 ‘Foxhound’ from “Pete”, and then it was all quiet again on a sweet sunny afternoon.

Shortly thereafter (again while heading north) I was stunned as a Tu-16 ‘Badger’ pulled up on our right wingtip in the tightest formation you could imagine. I waved to the pilot and he waved back. I broadcast the required HARVARD message (indicating that we were intercepted in international airspace) and then resumed our mission business. The Tu-16 stayed parked on our wingtip for the two hours or so. It was a beautiful thing to watch.

By this time we still had a lengthy launch window to cover and were running low on fuel, so we left the orbit and sensitive area to head to our tanker. The ‘Badger’ remained tucked into position. As we approached the tanker, their boom operator squeaked over the radio something like:

“COBRA 55 do you know you’re not alone?”

“Roger, we know.”

“What should I do?”

“Well, if he wants gas, give it to him.”

As we moved forward to the pre-contact position I noticed there was now a person with a huge movie camera in the plexiglas dome atop the fuselage aft of the cockpit. He filmed the entire air refueling procedure in close-up detail. After we had received our fuel I motioned for the BADGER to move into the recontact position (visions of a cover photo for Aviation Week danced in my head), but he declined. The pilot waved goodbye and headed south. I sent out our BROTHER message that our escort had departed and that was that!”

“As best as I can guess, the Soviets wanted detailed video of a boom air refueling to evaluate. As we know they stuck with the probe-and-drogue method, but this mission likely provided them with data on how the boom worked.

There was no Soviet ICBM launch that day, and we headed back to The Rock after a 10.2-hour sortie.”

Tell me something most people don’t know about Cold War spy flights?

“There were a lot more than U-2 overflights to Cold War reconnaissance. There were just 24 CIA U-2 overflights of the USSR from 4 July 1956 to 1 May 1960. From March to April 1956 there were 156 RB-47E/H overflights of the USSR, although this was the single largest event.”

“As best as I can guess, the Soviets wanted detailed video of a boom air refueling to evaluate. As we know they stuck with the probe-and-drogue method, but this mission likely provided them with data on how the boom worked.

There was no Soviet ICBM launch that day, and we headed back to The Rock after a 10.2-hour sortie.”

Tell me something most people don’t know about Cold War spy flights?

“There were a lot more than U-2 overflights to Cold War reconnaissance. There were just 24 CIA U-2 overflights of the USSR from 4 July 1956 to 1 May 1960. From March to April 1956 there were 156 RB-47E/H overflights of the USSR, although this was the single largest event.”

Comparatively there were tens of thousands of peripheral reconnaissance missions around the Communist bloc between 1946 and 1992. SAC averaged 50-60 per month at the height of operations, not to mention US Navy and allied-nation flights.

What is a popular myth about aerial reconnaissance?

“The single most popular myth is that these flights threatened the Soviet Union and were, in the words of US diplomat George Kennan, “indistinguishable from a state of war.”

We now know (to quote a book title) that the flights were far less provocative to Soviet leaders. Declassified documents from the Soviet era, interviews, and brilliant scholarship (such as William Taubman’s biography of Khrushchev) show that the flights had little impact beyond irritants and “theater” at the UN or in the pages of the New York Times. By the time of Stalin’s death in 1953, attacks on Western reconnaissance aircraft began to dwindle as Soviet defense capabilities improved sufficiently to identify and track peripheral missions without the need to attack them. The evidence is compelling, and by 1960 these flights had become so routine that the Soviets could actually predict the exact arrival of WC-135s on daily aerial sampling missions, for example, and these were never considered a threat (the 1960 RB-47H loss was purely political, a decision made by Khrushchev).”

Comparatively there were tens of thousands of peripheral reconnaissance missions around the Communist bloc between 1946 and 1992. SAC averaged 50-60 per month at the height of operations, not to mention US Navy and allied-nation flights.

What is a popular myth about aerial reconnaissance?

“The single most popular myth is that these flights threatened the Soviet Union and were, in the words of US diplomat George Kennan, “indistinguishable from a state of war.”

We now know (to quote a book title) that the flights were far less provocative to Soviet leaders. Declassified documents from the Soviet era, interviews, and brilliant scholarship (such as William Taubman’s biography of Khrushchev) show that the flights had little impact beyond irritants and “theater” at the UN or in the pages of the New York Times. By the time of Stalin’s death in 1953, attacks on Western reconnaissance aircraft began to dwindle as Soviet defense capabilities improved sufficiently to identify and track peripheral missions without the need to attack them. The evidence is compelling, and by 1960 these flights had become so routine that the Soviets could actually predict the exact arrival of WC-135s on daily aerial sampling missions, for example, and these were never considered a threat (the 1960 RB-47H loss was purely political, a decision made by Khrushchev).”

About the pilot

What is your rank and unit, and when did you serve?

“I entered the USAF as a Second Lieutenant in 1984 after commissioning at Officer Training School (“90 Day Wonder”). I had three operational assignments: 70th AREFS at Grissom AFB, IN, 24th SRS at Eielson AFB, AK, and the 38th SRS at Offutt AFB, NE. I separated from the AF as a Captain after returning from DESERT STORM in 1991.”

Which types have you flown?

During training I flew the T-41A, T-37B, and T-38A.

Operationally I flew 17 different types of ‘135 tankers, airborne command posts, and reconnaissance platforms [KC-135A, A(RT) D, E, E(RT) R, Q, EC-135C, G, L, TC-135S, W, and RC-135S, U, V, W, X]

I also flew the T-37B in the Accelerated Copilot Enrichment (ACE) program, and logged pilot time in the OA-37B and F-15D.

About the pilot

What is your rank and unit, and when did you serve?

“I entered the USAF as a Second Lieutenant in 1984 after commissioning at Officer Training School (“90 Day Wonder”). I had three operational assignments: 70th AREFS at Grissom AFB, IN, 24th SRS at Eielson AFB, AK, and the 38th SRS at Offutt AFB, NE. I separated from the AF as a Captain after returning from DESERT STORM in 1991.”

Which types have you flown?

During training I flew the T-41A, T-37B, and T-38A.

Operationally I flew 17 different types of ‘135 tankers, airborne command posts, and reconnaissance platforms [KC-135A, A(RT) D, E, E(RT) R, Q, EC-135C, G, L, TC-135S, W, and RC-135S, U, V, W, X]

I also flew the T-37B in the Accelerated Copilot Enrichment (ACE) program, and logged pilot time in the OA-37B and F-15D.

This site is in danger, due to a lack of funding, if you enjoy this and wish to donate you may do it here. Your donations, how ever big or small, keep this going. Thank you.

Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kitYou may enjoy these articles:

Top Combat Aircraft of 2030, The Ultimate World War I Fighters, Saab Draken: Swedish Stealth fighter?, Flying and fighting in the MiG-27: Interview with a MiG pilot, Project Tempest: Musings on Britain’s new superfighter project, Top 10 carrier fighters 2018, Ten most important fighter aircraft guns

11 comments