The 10 worst Royal Navy aircraft

‘Only a twenty foot margin for error’ That sounds fun, where do I sign up?

Considering they invented the aircraft carrier, Britain’s Royal Navy has really pulled out the stops ever since to field as many aircraft as possible that were too slow, too dangerous, too late, too expensive or sometimes all four. Not content with producing their own obsolescent deathtraps, the Senior Service also took on cast-offs from the RAF and bought in the occasional American dud to swell the numbers of inadequate aircraft crowding the decks of their too-small carriers. Narrowing down this underwhelming armada to a flotilla of merely ten was a daunting and difficult task. We hope you will agree this was a valuable endeavour and time well spent.

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. This site is in peril as it is well below its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here.

10. Parnall Peto

The Peto performs its famed Polaris impression

The Peto was, in its way, an excellent little aircraft but it was the realisation of a terrible idea if not a terrible flying machine. Tragically a single airframe (of two built) directly resulted in the deaths of 60 Royal Navy personnel, possibly the worst loss versus production ratio of any military aircraft. The Peto was designed for a seemingly ridiculous purpose, to serve as a scout aircraft for a submarine, in this case the Royal Navy’s largest, the M-class. The concept was also toyed with by the French, German, US and Japanese navies but only Japan pursued it with any seriousness or success. A diminutive machine for obvious reasons, the Peto had folding wings and was housed in a watertight hangar immediately ahead of the conning tower. The crew of the M2 were zealous in their attempts to launch the aircraft in the shortest possible time after surfacing. Probably a little too zealous as it turns out, witnesses on a passing ship, unaware that anything was amiss, saw M2 briefly surface, then submerge forever. When the wreck was discovered the hangar doors were found to be open: in their haste to launch the Peto the doors has been opened too early and the hangar flooded, dragging the M2, the Peto and sixty sailors to the bottom.

Flying the Phantom, British-style here

9. Curtiss Seamew

A thing of beauty is a joy forever

Most of the best aircraft operated by the Royal Navy during the second world war were of American origin and types such as the Wildcat, Corsair and Avenger dominated FAA flight decks for most of the conflict. There were, however exceptions to this rule and chief amongst them was the appalling Curtiss Seamew. 250 were allocated for British use but only 100 were delivered before the Royal Navy refused to take any more and sensibly demanded Vought Kingfishers instead. It’s not entirely surprising that the USN had tried to offload as many Seamews as possible onto their allies; the Seamew didn’t even win the competition that selected it for service. A rival design by Vought was judged superior but Vought were busy with the superlative Corsair and Curtiss had spare capacity so into production the Seamew went, and the inexplicably large total of 795 of these unpleasant aircraft were manufactured. If it had been merely slow and uninspiring (which it was) it could have been written off as a humdrum mediocrity but the Seamew was also dangerous. Its main tank could hold 300 gallons of fuel but it couldn’t take off with more than 80 gallons on board. The Ranger engine of the Seamew was prone to regular failure but even were it to run perfectly the Seamew had other nasty tendencies as, according to the ATA pilot Lettice Curtiss, ‘it was possible to take off in an attitude from which it was both impossible to recover and in which there was no aileron control’

The 10 worst British military aircraft here

8. Supermarine Seafire Mk XV

Thoroughbred or mule? The Seafire XV was both (It’s not a horse, Ed.)

The Spitfire’s experience at sea was not a wholly happy one. In the air the Sea-Spitfire retained all the qualities that had made the regular Land-Spitfire such a successful and popular fighter but revealed that the aircraft was essentially just too delicate for the rigours of operating from a carrier deck. The Merlin powered variants were bad enough but the first Griffon-engined Seafires really did not like being on carriers. They had a tendency to veer to the right on take-off, even with full opposite rudder applied, and smashing into the carrier’s island superstructure. Added to this was the unfortunate situation that the undercarriage oleo legs were still the same as the much lighter Merlin engined Spitfires, meaning that the swing was often accompanied by a series of hops as the oleo could not fully cope with the weight and torque of the aircraft. The weak undercarriage also conferred on the Seafire XV a propensity for the propeller tips to ‘peck’ the deck during an arrested landing and on some occasions led to the aircraft bouncing over the arrestor wires completely and into the crash barrier. Not ideal for a carrier aircraft and the RN offloaded the Seafire XVs onto the unsuspecting Canadians and French navies as soon as was possible. Tellingly both the Canadians and the French in turn replaced these aircraft (with the far more sensible Sea Fury and Hellcat respectively) after very brief carrier service.

7. Westland Wyvern

‘Note humped appearance of fuselage’ and terrified appearance of test pilot

A perplexing design described by Harald Penrose, Westland’s chief test pilot, as “very nearly a good aircraft”, the Wyvern suffered from the good old British problem of excessive development time, such that it was nudging obsolescence once committed to service. Part of the reason for this was not the fault of the design at all, the Wyvern had been designed initially to utilise the Rolls-Royce Eagle, a ludicrously complicated 46 litre H-block 24 cylinder sleeve valve piston engine (essentially a bigger Napier Sabre) that first ran in 1944 and delivered an impressive 3200 hp. Sadly for the Wyvern, the Eagle, though not without teething problems, fell victim to the wide-ranging cancellations of military projects immediately following the second world war that in one fell swoop effectively killed all non-turbine projects (even promising ones). Nonetheless the prototype Wyverns were Eagle powered and the sole surviving example is a never-flown example with the Eagle engine. Attention then swung to a promising turboprop, the Rolls-Royce Clyde rated at a lusty 4030 shaft horsepower. Fate was not to be kind to the Wyvern as Rolls-Royce themselves cancelled development of the Clyde due to the tiresome belief that pure jet engines were the way forward. This left but one suitable engine, the Armstrong-Siddeley Python and the Python was pretty woeful for carrier use. Slow spool-up time made for sluggish acceleration and a go-around or wave-off was a risky affair, the engine had a propensity to flame-out during catapult launches due to fuel starvation, and although the Python was supposed to be more powerful than the Eagle, the piston-engined prototype achieved a higher maximum speed and greater range than its Python powered production brethren a dismal seven years before the Wyvern even entered service. So saddled with a barely adequate power plant the enormous Wyvern attempted to operate from the decidedly small RN carriers of the 1950s. Weighing 650 pounds shy of a loaded Dakota the Wyvern could not be described as ‘sprightly’ and ultimately its main claim to aviation immortality derives not from any superlative quality of the aeroplane itself but from a desperate desire to escape it: Lt. B. D. Macfarlane made history on 13 October 1954 when he performed the world’s first successful ejection from under water after his aircraft had ditched on launch and been cut in two by the carrier. Of 127 built, 39 were lost to accidents and despite eight years of development flying, the career of the only turboprop fighter to see service was to last a mere four.

6. Fairey Swordfish

Even during times of war it is considered bad form to attack deck hockey matches on your own carrier

Yes, yes, I know. The Swordfish was probably the most successful aircraft the Royal Navy has ever operated. If it had achieved nothing else, the attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto would have ensured the Swordfish’s immortality yet it also crippled the Bismarck and operated throughout the war, apparently sinking a greater tonnage of Axis shipping than any other Allied aircraft (though this depends on which sources you believe as the American Curtiss Helldiver, rejected for service by the FAA due to its “appalling handling”, is also claimed to be the top Allied anti-shipping aircraft by tonnage sunk). However, this glowing service record was not achieved because of the outstanding qualities of the aircraft but rather in spite of its shortcomings. In other words, imagine how much more might have been achieved had the Royal Navy been operating a modern aircraft of decent performance with reasonable striking power rather than the outdated Swordfish with its first world war performance and modest armament. The Swordfish stands as testimony to the appalling neglect of naval aviation in Britain throughout the inter-war period.

The best aspects of the Swordfish were straightforward – it was reliable, simple and easy to fly. It made for an excellent training aircraft but then so did its cousin, the Fairey Battle which regularly features in lists of the worst aircraft of the war. Yet the Battle was better armed, longer ranged and an order of magnitude faster than the poor Swordfish. Committed to similar combat conditions, the Swordfish was even less able to survive than the oft-maligned Battle. The Swordfish was appallingly slow, not very manoeuvrable and effectively defenceless when faced with even the most underwhelming of fighter aircraft. It is telling that in all its most famous successes the Swordfish never faced an enemy aircraft of any kind: it simply couldn’t. Bismarck had no air cover and the Taranto operation was flown at night. By contrast, in February 1941 all of the Swordfish force sent to attack the German capital ships engaged in Operation Cerberus, the so-called ‘Channel Dash’, were destroyed by fighters or flak. Of the eighteen aircrew involved, only five survived. It was dangerous to operate even a powerful anti-shipping aircraft such as the Beaufighter in European waters until the very end of the war, in a Swordfish it was effectively suicidal. Ultimately the success the Swordfish experienced was due to a combination of extremely canny tactical deployment by the Navy and the exceptional heroism and skill of its aircrews, not through any outstanding combat quality of the aircraft itself.

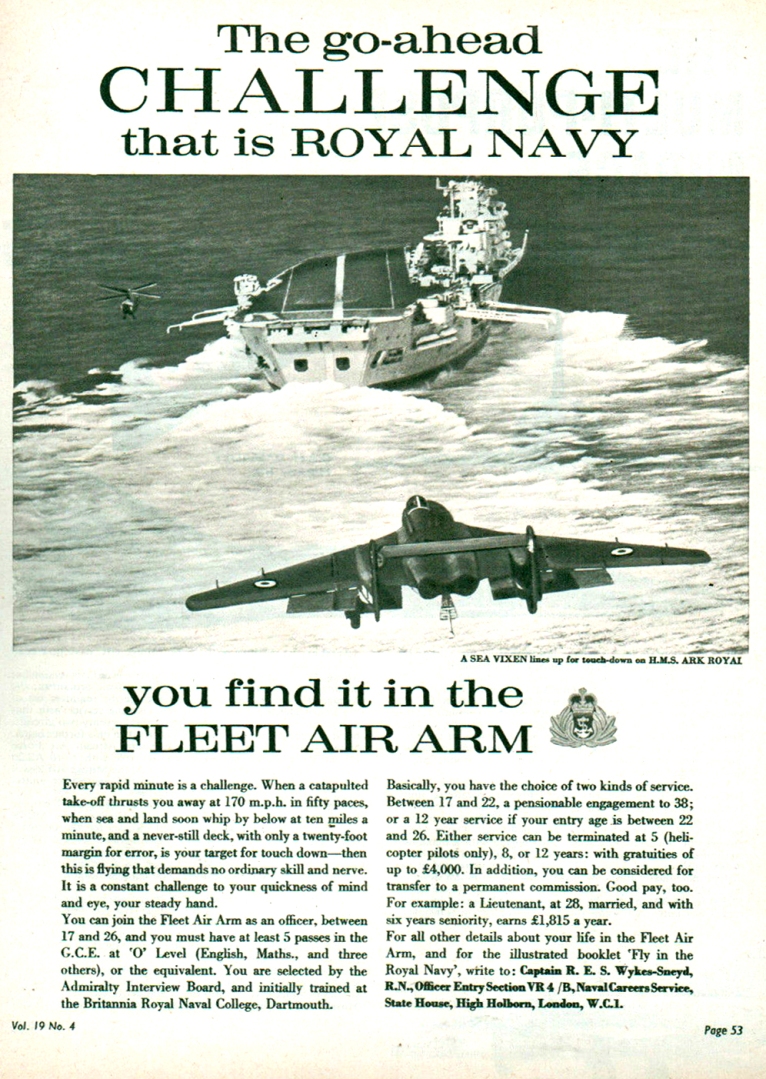

5. de Havilland Sea Vixen

‘I’m still better than a Scimitar!

Had it entered service with the RAF in the early fifties de Havilland’s last fighter would probably be remembered as a great aircraft. But it didn’t and the Royal Navy’s Sea Vixen turned out to be a death trap. 145 Sea Vixens were built, of these 37.93% were lost over the type’s twelve-year operational life. More than half of the incidents were fatal. The Sea Vixen entered service in 1959 (despite a first flight eight years earlier), two years later than the US Navy’s Vought F-8 Crusader. The F-8 was more than twice as fast as the Sea Vixen, despite having 3,000Ibs less thrust. The development of the Sea Vixen had been glacial. The specification was issued in 1947, initially for an aircraft to serve both the FAA and the RAF. The DH.110 prototype first flew in 1951, and one crashed at the Farnborough airshow the following year. This slowed the project disastrously, the RAF ordered the rival (and inferior) Gloster Javelin whilst DH and the RN focused on the alternative DH.116 ‘Super Venom’. Once the project became prioritised again, it was substantially redesigned to fully navalise it. Then, when the Royal Navy gave a firm commitment, it requested a radar with a bigger scanner and several other time-consuming modifications. All of which meant it arrived way too late, as is compulsory for all British postwar aircraft. Meanwhile its peer, the F-8, remained in frontline service until 2000, its other contemporary, the F-4, remains in service today. The Sea Vixen retired in 1972. Fifty-one Royal Navy aircrew were killed flying the Sea Vixen.

What’s the new Hawk like? Interview with a Hawk pilot here

4. Blackburn Firebrand

Firebrand: Waste of a perfectly good Centaurus? Discuss

Despite being a decidedly purposeful looking aircraft the Firebrand was a pilot-killer. The specification for the type was issued in 1939 and it first flew in 1942 but did not enter service until after the war had ended. Despite this luxuriously long development (whilst the Navy attempted to decide whether they wanted a fighter or torpedo bomber or both and toyed with Sabre or Centaurus engines) it was an utter pig, with stability issues in all axes and a tendency to lethal stalls. There was a litany of restrictions to try and reduce the risks, including the banning of external tanks, but it still remained ineffective in its intended role and dangerous to fly. Worse still, instead of trying to properly rectify the problems, the FAA started a witch hunt of those pilots who dared to speak the truth about the abysmal Firebrand. Only two Firebrand squadrons formed, of which the flying complement was heavily, if not entirely made up of qualified flying instructors, suggesting only the most experienced pilots could be trusted with this unforgiving monster. Talking of experienced pilots, Eric Brown, arguably the most experienced naval pilot of all time had this to say on the Firebrand: “It was never a pilot’s aircraft – how could it be when he sat nearer the tail than the nose; as a deck-landing aeroplane it was a disaster and it was incapable of fulfilling competently either the role of torpedo-bomber or that of fighter, but it was built like a battleship – and there were to be those that would say that it flew like one”. Even so, somehow it managed to remain in service until 1953, double the length of time achieved by its successor, the similarly benighted Wyvern.

The world’s worst air force here

3. Blackburn Roc

Roc: the wrong concept applied to the wrong airframe at the wrong time

Described as “a constant hindrance” by the commander of 803 squadron the Roc was an unhappy outgrowth of the mediocre but adequate Skua. The Roc essentially comprised the same airframe but saddled it with a gun turret weighing about a ton and adding enough drag to lower the speed of the already pedestrian Skua by some 30 mph. A maximum speed (at sea level) of 194 mph was simply suicidal for a fighter facing the Luftwaffe’s ‘109s. Add terrible agility, no forward-firing guns and you get the idea. Wisely, the military decided the best use for it was as a static machine-gun post but not before the Roc had seen some action and scored one confirmed kill. Remarkably the Roc’s sole victim was a Junkers 88, an aircraft capable of flying over 100 mph faster than the lumbering Roc.

2. Supermarine Scimitar

A Scimitar holidaying on USS Forrestal wonders why it can’t stay on this lovely big carrier forever

The Scimitar was a case of too much too soon and its shortcomings were paid for in pilot’s lives. It suffered an appalling attrition rate of 51 per cent yet was a worse fighter than the Sea Vixen and a worse bomber than the Buccaneer. To add insult to injury it was also extremely maintenance heavy. Nonetheless the Royal Navy gamely took the Scimitar, an aircraft so dangerous that it was statistically more likely than not to crash over a twelve year period, and armed it with a nuclear bomb. Prior to this one example crashed and killed its first Commanding Officer in front of the press. The Scimitar was certainly not Joe Smith’s finest moment. It was the last FAA aircraft designed with an obsolete requirement to be able to make an unaccelerated carrier take-off, and as a result had to have a thicker and larger wing than would otherwise be required. Only once did a Scimitar ever make an unassisted take-off, with a very light fuel load and no stores, and then just to prove that it could be done.

1. HMA No.1 ‘Mayfly’

Does my back look broke in this: £28,000 of aircraft lost due to a light breeze

It’s fair to say Naval aviation started badly in the UK. In 1909, inspired by German Zeppelin developments, which despite their later fame as bombers were originally intended to operate as long ranged Naval scouts, the Royal Navy commissioned Vickers, at great expense, to build the world’s finest airship, intended to carry 20 crew in considerable comfort and capable of cruising at 40 knots (46 mph) for 24 hours. The aircraft that emerged was in many ways revolutionary, it had equipment to recover water from the engine exhaust to balance the weight of fuel as it was consumed, the structure made extensive use of the brand new alloy duralumin, the upper skin used reflective aluminium powder in its coating to minimise heat absorption, the control gondolas were watertight so that the airship could be operated off the surface of they sea and the hull applied the latest aerodynamic work and was claimed to offer 40% less resistance to the air than contemporary Zeppelins. Some time before trials were to be attempted the airship’s crew started training and it was charmingly noted ‘They lived on board the airship and suffered no discomfort at all although no provision had been made for cooking or smoking on board’. Over the course of the following year static trials were carried out and it was realised that the ship was too heavy. There followed a series of cack-handed modifications which reduced the weight of the aircraft by three tons. Gone was the water recovery system along with half the aerodynamic control surfaces and, most seriously, the external keel of the airship. This last modification was strongly objected to by a draughtsman from Vickers called Hartley Pratt who claimed it would prove disastrous but his warnings were ignored and he left the company. The airship was being removed from its floating shed in a light wind on the 24th September 1911 when cracking sounds were heard from amidships and it broke in two. The 156 meter long aircraft had never flown, which was lucky, given its dangerously weak structure. As it was no one had been even slightly hurt in what was probably the least dramatic air crash of all time.

Even without provision for cooking or smoking, His Majesty’s Airship No.1 had ultimately proved more successful as a house than as a flying machine.

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. This site is in peril as it is well behind its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here.

The more you give, the more we can give you 🙂

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. Our site is absolutely free and we have no advertisements. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. At the moment our contributors do not receive any payment but we’re hoping to reward them for their fascinating stories in the future.

Elegant man pouring beer from bottle into glass, (B&W)

Have a look at How to kill a Raptor, An Idiot’s Guide to Chinese Flankers, the 10 worst British military aircraft, The 10 worst French aircraft, Su-35 versus Typhoon, 10 Best fighters of World War II , top WVR and BVR fighters of today, an interview with a Super Hornet pilot and a Pacifist’s Guide to Warplanes. Was the Spitfire overrated? Want something more bizarre? The Top Ten fictional aircraft is a fascinating read, as is The Strange Story and The Planet Satellite. The Fashion Versus Aircraft Camo is also a real cracker. Those interested in the Cold Way should read A pilot’s guide to flying and fighting in the Lightning. Those feeling less belligerent may enjoy A pilot’s farewell to the Airbus A340. Looking for something more humorous? Have a look at this F-35 satire and ‘Werner Herzog’s Guide to pusher bi-planes or the Ten most boring aircraft. In the mood for something more offensive? Try the NSFW 10 best looking American airplanes, or the same but for Canadians.

“If you have any interest in aviation, you’ll be surprised, entertained and fascinated by Hush-Kit – the world’s best aviation blog”. Rowland White, author of the best-selling ‘Vulcan 607’

I’ve selected the richest juiciest cuts of Hush-Kit, added a huge slab of new unpublished material, and with Unbound, I want to create a beautiful coffee-table book. Here’s the book link .

I can do it with your help.

From the cocaine, blood and flying scarves of World War One dogfighting to the dark arts of modern air combat, here is an enthralling ode to these brutally exciting killing machines.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes is a beautifully designed, highly visual, collection of the best articles from the fascinating world of military aviation –hand-picked from the highly acclaimed Hush-kit online magazine (and mixed with a heavy punch of new exclusive material). It is packed with a feast of material, ranging from interviews with fighter pilots (including the English Electric Lightning, stealthy F-35B and Mach 3 MiG-25 ‘Foxbat’), to wicked satire, expert historical analysis, top 10s and all manner of things aeronautical, from the site described as

“the thinking-man’s Top Gear… but for planes”.

The solid well-researched information about aeroplanes is brilliantly combined with an irreverent attitude and real insight into the dangerous romantic world of combat aircraft.

FEATURING

- Interviews with pilots of the F-14 Tomcat, Mirage, Typhoon, MiG-25, MiG-27, English Electric Lighting, Harrier, F-15, B-52 and many more.

- Engaging Top (and bottom) 10s including: Greatest fighter aircraft of World War II, Worst British aircraft, Worst Soviet aircraft and many more insanely specific ones.

- Expert analysis of weapons, tactics and technology.

- A look into art and culture’s love affair with the aeroplane.

- Bizarre moments in aviation history.

- Fascinating insights into exceptionally obscure warplanes.

The book will be a stunning object: an essential addition to the library of anyone with even a passing interest in the high-flying world of warplanes, and featuring first-rate photography and a wealth of new world-class illustrations.

Rewards levels include these packs of specially produced trump cards.

I’ve selected the richest juiciest cuts of Hush-Kit, added a huge slab of new unpublished material, and with Unbound, I want to create a beautiful coffee-table book. Here’s the book link .

The Swordfish makes so much more sense if you think of it as an early attack helicopter – its flight envelope is fairly similar to a lot of helos, and the stuff FAA helos do is basically the same mission set. (A Whirlwind/H-19 had a maximum speed of 109mph, rate of climb of 910 ft/min, with 750hp. A Swordfish got 139mph, 870ft/min out of 690hp. Ceiling was 13000ft vs 16000ft, range 334 vs 552nm.)

What … no Short Seamew? Surely worse than a Swordfish, which at least had a noble record, albeit with the sacrifice of some exceptionally heroic aircrew. The Swordfish also pretty-much outlasted its intended replacement, the Albacore.

Your comments on the Scimitar were incorrect. The CO landing on HMS Victorious did not die because of the aircraft crashing at all. The aircraft did a perfect landing, but the arrestor wire was set wrong, allowing the aircraft to roll over the end of the angled deck and into the water. The pilot was unable to get out of the cockpit and sank trapped inside.