Category: Uncategorized

Top 10 Japanese Aircraft Of World War II

“In the field of machinery the Japanese mind is at a peculiar disadvantage. They are able to turn out an exact copy of any mechanism that comes into their hands, but the type of mechanical imagination which went into its original creation—which, for want of a better term, is sometimes known as Yankee ingenuity—they are at a loss to duplicate.”

In the lead up to, and during the Second World War it seems the US was all too willing to believe its own propaganda on Japanese industrial prowess, and although official intelligence material never descended to the level of the drivel quoted above (from ‘Mechanix Illustrated’) it did repeatedly assume that all Japanese aircraft were copies of Western types. Whilst this was broadly true in the twenties, American Intelligence never noticed (or possibly cared) that the Japanese had attained parity with (and in some areas surpassed) the West by the latter half of the 1930s. This attitude was so ingrained in American thinking that a Western aircraft needed to be conjured up for any new Japanese type to be a copy of (try finding the aircraft that the Kyūshū J7W 震電, ‘Shinden’ (Magnificent Lightning) was copied from: you will struggle). This is particularly evident in the psychological effect the Mitsubishi Zero had on its foes in 1942, an effect only multiplied by the lens of racism through which the Japanese people were inevitably observed. This was followed by a weird scramble to find what American aeroplane the Zero was copied from (Spoiler alert: it wasn’t). It should be noted that extreme racialism and racism was also institutional in Imperial Japan, where the official line often pushed was the notion of the Japanese as a supreme master race.

Join us as we take a look at some other masterpieces of Japanese indigenous design, whether conceived when the Empire swept all before it, or suffering the crushing reality of total defeat.

10. Mitsubishi Ki-83

キ83 (Ki 83)

Produced by a team under Tomio Kubo, who also designed the superlative Mitsubishi Ki-46, the Ki-83 could have been the finest twin-engined fighter of the war. As things turned out it became an obscure footnote in aviation history.

The result of an Imperial Army specification calling for a high altitude, long-range heavy fighter the aircraft that emerged from Mitsubishi’s experimental workshop was possibly the most aerodynamically clean radial engined aircraft ever built and possessed spectacular performance. As well as recording the highest speed attained by any Japanese aircraft built during the war, the Ki-83 was blessed with remarkable agility for such a large aircraft and was fully aerobatic at high speeds. It is recorded to have been capable of executing a 2200 feet loop at 400 mph in 31 seconds. Compared to its direct US equivalent, the F7F Tigercat which also failed to see meaningful service during the war*, the Ki-83 had the same range but was faster and more manoeuvrable. Armament comprised the potent combination of two 30-mm and two 20-mm cannon, all firing through the nose. Unfortunately for this superlative warplane, its timing was appalling.

First flown in November 1944, tests were often interrupted by American air raids and of the four prototypes known to have been completed, three were damaged or destroyed by bombing. The crippling raids by B-29 Superfortresses were also the reason that the Ki-83 never entered production: despite the enthusiasm of both the Army and Navy, by the time it was flying all aircraft manufacturing was focused on interceptors to combat the B-29 and the Ki-83 never received a production order. After the war the sole surviving prototype was evaluated in the US and received glowing praise. With the higher octane fuel available in America the Ki-83 ultimately recorded a speed of 473 mph. Despite being earmarked for preservation the only Ki-83 to survive the war and arguably the finest wartime fighter produced in Japan was last recorded at Orchard Field Airport in Illinois in 1949. It is presumed to have been scrapped there in 1950.

*The first operational F7F sorties took place on 14 August 1945, the war ended the following day.

The Ki-83 made our list of the ten best aircraft of World War II that failed to see service.

From this angle the small window in the fuselage for the optional second crew member is visible just above the tailplane. The outlet at the rear of the nacelle is the turbocharger exhaust.

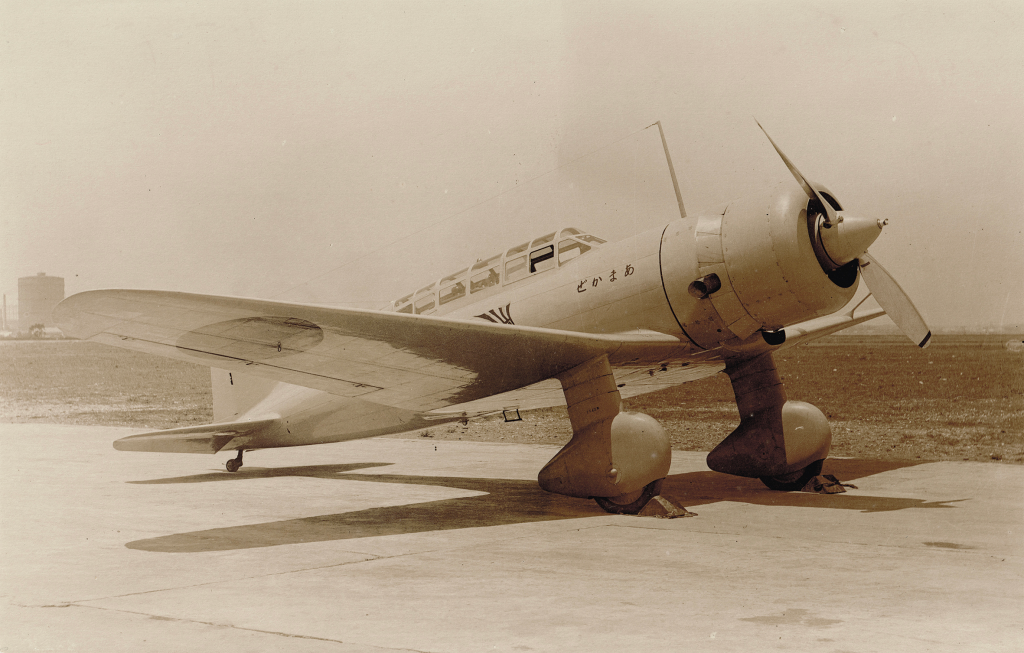

9. Mitsubishi Ki-15

九七式司令部偵察機, Kyunana-shiki sireibu teisatsuki (Army Type 97 Command Reconnaissance aircraft)

雁金, ‘Karigane’ (Wild Goose)

Although outclassed fairly quickly, the racily art-deco styled Mitsubishi Ki-15 was a brilliant harbinger of what the Japanese aviation industry was capable of and was the first Japanese aircraft to appear in Europe when in 1937 a single example owned by the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, named ‘Kamikaze’ (before that word had any sinister connotations and considered “delightfully named” by ‘Biggles’ creator WE Johns in ‘Popular Flying’), flew from Tokyo to London for the coronation of George VI.

Despite much of the press coverage of this flight turning out to be predictably obsessed with the racial make-up of the Kamikaze’s crew, a process made all the more fun for reporters by the fact that navigator Kenji Tsukagoshi was half British (though attempts to find at least one European parent for pilot Masaaki Iinuma to ‘explain’ his aerial proficiency proved fruitless), a few reports managed to notice that the aircraft was a totally indigenous design, such as British publication ‘Flight’ which reported: “Contrary to expectations, this Mitsubishi monoplane… and its engine do not appear to have built under direct licence from any American firms” but very few pointed out that the 51 hour, 17 minute, 23 second flight over a distance of 15,357 kilometres occurred without any mechanical trouble at all and at a speed unattainable by virtually any contemporary military aircraft. Just to put the icing on the cake, after a whistle-stop tour of major European capitals, Iinuma and Tsukagoshi flew all the way back to Japan in four days, again with no mechanical issues. Given that a mere three years earlier most of the entries into the MacRobertson Air race to Australia had broken down or crashed or taken an insanely long time to reach their destination due to short range and running repairs, this sort of thing should have acted as a sharp wake up call to Western observers (but didn’t).

The less peaceful version of the Ki-15 was utilised as a reconnaissance and light attack aircraft in the Second Sino-Japanese war, being arguably the first truly modern combat aircraft to see service in that theatre, and in developed form during the opening stages of World War II, when its speed was still good enough to render it difficult to intercept, thus setting a precedent for the superlative Ki-46.

Support The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes: Volume 3 here

8. Mitsubishi A6M

零式艦上戦闘機, rei-shiki-kanjō-sentōki (Type 0 Carrier-based Fighter)

零戦 ‘Rei-sen’ (Zero Fighter)

“I look like Robert de Niro, I drive a Mitsubishi Zero” sang Billy Bragg on his 1991 single ‘Sexuality’, a rare namecheck for a Second World War aircraft in the realm of late 20th century popular music, and although Billy Bragg looks nothing like Robert de Niro and obviously never having sat in, let alone ‘driven’ a Mitsubishi Zero, the very presence of this most famous of Japanese aircraft lends an effortless cool to the song that the inclusion of, say, a Vickers Vildebeeste or a Brewster Buffalo would fail to impart.

The Zero was one of the greatest aircraft of all time, the only Japanese aircraft to be commonly referred to by its official designation by both sides in the Pacific (the odd name ‘Zero’ derives from the last two digits of the Japanese year 2600, during which it entered service and the official allied reporting name ‘Zeke’ never entirely caught on) and the idea of leaving it out of a Top Ten of Japanese aircraft is ludicrous, let alone a Top Ten of Japanese WWII aircraft. However, unlike such aircraft as the Spitfire, the Zero failed to be developed sufficiently to remain in the vanguard of international fighter aircraft and was essentially a spent force by 1945, despite being produced in greater numbers than any other Japanese aircraft before or since. Nonetheless, for a period of two years or so it was, without doubt, the most psychologically shocking aircraft in the sky and the most advanced carrier fighter in the world.

The fact that the Zero caused such a stir amongst the Allies is perplexing: the aircraft had appeared over China well before Pearl Harbor and was a known quantity amongst Chinese aviators and, perhaps more pertinently given the majority if its future foes, the US personnel of the American Volunteer Group (the famed ‘Flying Tigers’). A captured Zero was in Chinese hands as early as February 1940 and was flown and inspected by an American team who sent a highly detailed report to Washington. This report appears to have been filed before it was read as the overriding response to the Zero’s capability once Allied fliers met it in combat was horrified surprise. But the Zero was, after all, immediately preceded by the Mitsubishi A5M which Western observers seemingly failed to notice was the first cantilever monoplane carrier fighter in the world.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Soviet World War II Combat Aircraft (but were afraid to ask) here

Despite the suggestion of a swathe of American types that the Zero was alleged to be a copy of, it was, of course, a superlative example of indigenous design led by the brilliant Jiro Horikoshi. Its specification was so challenging that Nakajima didn’t even enter a rival tender: they deemed it impossible to meet. As it turned out, Horikoshi had to use a brand new aluminium alloy (‘Extra Super Duralumin’) which had only been developed by Sumitomo in 1936 to be able to make the Zero light, yet strong enough to fulfil the speed, range and manoeuvrability requirements. The Zero was utterly dominant from its appearance in 1940 to the latter end of 1942, remaining a dangerous opponent to the war’s end in the hands of an experienced pilot. Unfortunately for the Japanese, experienced pilots were in desperately short supply for the latter part of the conflict due to the horrific attrition of the Pacific war. But for two glorious years, if you were Japanese at least, the Zero reigned utterly supreme over land and ocean.

7. Mitsubishi Ki-67

四式重爆撃機, Yon-shiki jū bakugeki-ki (Type 4 Heavy Bomber)

飛龍 ‘Hiryū’ (Flying Dragon)

On the whole, Japanese bombers of WWII were not a particularly inspiring bunch. The Navy’s Mitsubishi G4M for example, whilst boasting a beautifully streamlined airframe and spectacular range, was prone to burst into flames if on the receiving end of merely a smouldering glance. The Army’s Nakajima Ki-49, the immediate predecessor of the Hiryū, though less overtly flammable, was disappointing: its bombload meagre and although intended to operate without an escort, its survival was anything but assured against any modern fighter. The sparkling performance of the Ki-67 therefore comes as something of a surprise and the Army were utterly delighted with it.

It should be noted that the contemporary Japanese definition of a ‘heavy’ bomber was not the same as that of other nations and the Ki-67 would have been described as a medium bomber in any other air force. Furthermore its published bomb load and range of 1,070 kg and 2,800 km respectively don’t sound that brilliant when compared with, say, the earlier B-25H Mitchell which could carry more than 2,000 kg and fly 2,170 km. However, published figures even today seem determined to maintain contemporary Allied propaganda in that, whilst not exactly a lie, they suggest the B-25 is better than it actually was, as it could either carry 2,000 kg or fly 2,170 km, not both, the range quoted was only possible with a much reduced load. The Ki-67 on the other hand was quite capable of flying 2800 km with its 1,070 kg bomb load. It could also do so at a speed the B-25 could only dream of and possessed an agility unmatched by any other medium bomber. The Hiryū was not only the finest bomber built by Japan, it was also one of the best aircraft in its class worldwide. So impressive was its performance and manoeuvrability that it was developed into a fighter, a seemingly insane development process as what other aircraft considered a heavy bomber has ever been adapted into a fighter?* The Ki-109 which entered limited production was ridiculously heavily armed with a 75-mm cannon in the nose and intended as a B-29 interceptor but its ceiling was insufficient to attack the high-flying Boeings.

Far more successful in its original intended role as a bomber, the Ki-67 had the misfortune to emerge into a world where Japanese forces were everywhere being pushed back and assailed by vast quantities of Allied aircraft. The Hiryū saw considerable action during its relatively brief service, attacking the US 3rd Fleet off Formosa (now Taiwan) and the Ryukyu Islands and later being used at Okinawa, in China, French Indochina (now Vietnam) Karafuto (now Sakhalin) and against B-29 airfields on Saipan and Tinian. Once the Japanese high command had accepted the use of humans as a missile guidance system in the form of the kamikaze the Ki-67 was used as a basis to develop this approach to its depressingly logical conclusion, the Ki-167 桜団 ‘Sakura-dan’ (Cherry blossom), ‘special attack’ bomber, which carried a 2.9 tonne thermite shaped charge in a large dorsal fairing intended to destroy fortified positions when crashed into them (in tests the charge proved capable of destroying a tank from a distance of 300m, simply through the power of directional blast). Details of the Ki-167’s production and use are obscure and although records are missing, there is photographic evidence that the aircraft definitely existed. It appears that around five examples may have attempted operational missions, thankfully none of these horrific machines ever hit an enemy target, being either shot down or lost to technical issues. An ignominious end to the career of an outstanding aircraft.

*Yeah yeah, the B-17 (kind of).

Hush-Kit gives its readers a lot, if you feel this massive effort deserves support then head over to Patreon and subscribe.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1.

Vol 2 can be pre-ordered here.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 here and Vol 2 here

6. Kawasaki Ki-100

五式戦闘機, Go-shiki sentouki (Type 5 Fighter)

Few fighter aircraft in history have made a successful switch from an inline powerplant to a radial (or vice versa) but one of the finest examples of this rare breed was the Ki-100 and its existence was very much a case of force majeure rather than any considered process. The Ki-61 飛燕, ‘Hien’ (Flying Swallow’) from which it was derived was a fine fighter, noted by Allied pilots after its appearance during 1943 for its unusual toughness compared to previous Japanese fighters. As usual, Allied intelligence scouted around for whatever western type the Ki-61 was a copy or licence-built version of and thought maybe it was something Italian, due to its superficial resemblance to the Macchi MC 202, this apparently informing the choice of its reporting name: ‘Tony’. To be fair, in this case they were half right as the Ha-140 engine of the Ki-61 was in fact a licence-built Daimler-Benz DB 601. Unfortunately for Kawasaki, engine supply had never kept up with airframe production, and even if it had, the Ha-140 was proving highly troublesome in service. So much for German technical prowess. By December 1944, 200 engineless Ki-61 airframes were stored in the open at Kawasaki’s factory at Kagamigahara and the situation became totally untenable after a B-29 raid on the Akashi engine plant on 19 January 1945 effectively ended production of the Ha-140. This added considerable impetus to ongoing work to re-engineer the Ki-61 to accept the radial Ha-112 engine, which was in relatively plentiful supply and possessed much better reliability.

Reflecting the desperation of Japan in the last year of war, the conversion of the first Ki-61 to receive the Ha-112 took place in just seven weeks. The new engine was nearly twice as wide as the inline Ha-140, possessed a different thrust line and was 45 kg lighter. Takeo Doi, chief designer of both the Ki-61 and Ki-100 was not keen on the engine change and expressed doubt that the conversion would be successful but in the absence of any viable alternative the work went ahead. Kawasaki followed the same process that Hawker in the UK had earlier followed in the radial engine Tempest II and (ahem) ‘based’ the engine mounting on that of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. The resulting aircraft exceeded even the most optimistic expectations of the design team and utterly vindicated the decision to re-engine: although marginally slower than the Ki-61, the new Ki-100 could outclimb and outmanoeuvre the previous fighter. Tested against a captured P-51C Mustang the Ki-100 was found to be slower but much more manoeuvrable and could out-dive the American aircraft. Given pilots of equal ability, a dogfight would always favour the Ki-100 – though it was admitted the P-51 could break off and escape at will. Against the F6F Hellcat, the Ki-100 was believed to be superior in every regard.

The Top 10 US Navy aircraft of World War II here.

Sadly for Japan, the Ki-100 only entered service in April 1945 but did see enough service to be considered the most reliable of the Japanese Army’s fighters. In combat, when flown by experienced aircrew (of which few were left by spring 1945), the Ki-100 proved formidable. On 3 June 1945 for example, the 244th Sentai claimed seven Corsairs destroyed and in a huge dogfight with a large formation of Hellcats on 25 July, 12 F6Fs were claimed shot down. It is hardly surprising that the Ki-100 was highly popular with pilots, what is totally remarkable is that the entire career of the Ki-100, from design conception to final surrender took place in a mere 10 months.

5. Aichi D3A

海軍九九式艦上爆撃機, Kaigun kyuukyuu shiki kanjou bakugekiki (Type 99 Carrier-based bomber)

Though the Ju 87 Stuka remains the archetypical dive bomber of the war, it performed most of its deadly work on land. The D3A was the preeminent Axis dive bomber at sea, sinking more Allied warships than any other Axis aircraft and was the first Japanese aircraft to bomb an American target when the Aichi craft spearheaded the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The US edition of The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 comes out April 2nd 2024…BUT between you and me, you can already pre-order it here and ensure your copy is reserved before it sells out here.

Aichi was a watch manufacturer that decided it was time to get into the aviation field in the 1920s and throughout the interwar years it maintained a close partnership with Heinkel, despite the terms of the Treaty of Versailles forbidding German military aircraft research or production. However, the Japanese delegate on the League of Nations inspection team charged with monitoring this situation simply told Heinkel in advance when they were coming and Heinkel made sure nothing illicit was ever found when they visited: a most satisfactory arrangement for all concerned. The Heinkel influence is clear to see in the D3A with its beautiful elliptical wing, closely related to Heinkel’s own He 70 ‘Blitz’. By the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, the D3A was a proven combat aircraft, having been in action over China for two years beforehand, but the Allies once again decided that this Japanese dive bomber was of no huge concern even as German dive bombers were delivering psychologically terrifying precision strikes across mainland Europe.

Proving that psychologically terrifying precision strikes were not the preserve of the Luftwaffe alone, the D3A opened its WWII account at Pearl Harbor, where admittedly all the ships were conveniently stationary. It then followed this up by sending three US destroyers to the bottom in February and March of 1942 and causing havoc amongst Royal Navy shipping in the Indian Ocean during April, culminating in the sinking of HMS Hermes, the world’s first purpose-built aircraft carrier. During the Indian Ocean raid, D3As achieved hits with 80% of their bombs, against manoeuvring ships at sea which was an incredible success rate. These post-Pearl Harbor attacks were conducted solely by the D3A but most of the successful strikes carried out by the Aichi aircraft were conducted in concert with the Nakajima B5N torpedo bomber, in exactly the same way that the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver would later ride roughshod over Japanese shipping in concert with the Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bomber.

The glory days for the D3A were very much the initial two years of the war, when the surprising agility and adequate performance of the Aichi dive bomber saw it utilised as a fighter aircraft on occasion but the inexorable improvement in Allied fighters saw the D3A gradually outclassed by its enemies, despite the introduction of the aerodynamically improved D3A2. The much faster Yokosuka D4Y 彗星, ‘Suisei’ (Comet) took over the dive bomber role from late 1943 onwards by which time most of the fleet carriers had been lost, along with veteran Japanese aircrew, and the D4Y could never repeat the remarkable success of its forebear. Yet even once totally outdated the D3A could still inflict terrible damage on its enemies: a D3A sank the American destroyer USS William D Princeton as late as 10 June 1945 in a kamikaze attack.

4. Kawanishi N1K-J

紫電, ‘Shiden’ (Violet Lightning)

The Japanese kept converting heavy bombers into fighters and charming newspaper-owned monoplanes into attack aircraft so it should come as no surprise perhaps that the Navy’s finest landplane fighter of the war should have derived from a seaplane. There were several instances of floats being added to WWII fighters to create a waterborne combat aircraft, the Spitfire, F4F Wildcat, Fiat CR.42 and even the Blackburn Roc were all subjected to this process for example, though only the Zero would see combat in its floatplane form (as the Nakajima A6M2-N). The N1K-J was the only fighter to apply the process in reverse when the float was removed from the powerful N1K1 強風, ‘Kyōfū’ (Strong Wind) floatplane fighter and replaced with wheels to create the N1K-J Shiden. The resulting aircraft, though essentially a lash-up, proved faster than the Zero and had a better range than the J2M Raiden interceptor and was thus rushed into production.

Compromised by the mid-wing configuration of the Kyōfū, intended to keep it clear of spray, the initial N1K-J required unusually long landing gear which were the source of much trouble but in the air the aircraft proved exemplary, demonstrating an excellent turn of speed and a truly remarkable manoeuvrability, boosted by a mercury switch that automatically measured angle of attack and extended the flaps during turns, a system known as the ‘combat flap’. A redesign to eradicate the N1K-J’s most obvious flaw, its mid-mounted wing, saw the aircraft appear in a low-wing configuration as the N1K2-J 紫電改 Shiden-Kai (Kai meaning ‘modified’) with a simplified and lightened structure that consisted of fewer parts and could be built in fewer man hours whilst boasting improved performance. Unfortunately, B-29 raids on the Kawanishi factories meant that only 415 of the improved variant were produced compared to 1007 of the original N1K-J conversion. Both types were somewhat compromised by the intermittent reliability of the Nakajima Homare engine but there was no obvious alternative and the same issues were plaguing other Japanese aircraft. In combat, when the engine was running properly, the Shiden proved formidable, even against the latest Allied fighters. On one occasion for example, the Corsairs of VFM-123 were surprised by Shidens which were mistaken by the US pilots for Hellcats, and a 30-minute aerial combat ensued. Three Corsairs were shot down and another five were damaged while three other F4Us were so badly damaged they were dumped at sea after recovering on their carrier. The Corsairs claimed 10 Japanese aircraft destroyed, but in reality no Japanese aircraft was lost to the F4Us. The reputation of the Shiden was also somewhat magnified by its role as the sole equipment of the 343 Kōkūtai, formed on 25 December 1944 as a particularly unwelcome Christmas present for the Allies. This unit was formed of the Navy’s most experienced surviving fighter pilots, such as Saburo Sakai and Naoshi Kanno, and was equipped with the finest aircraft available. Even during the chaotic conditions prevalent over Japan during 1945, the 343 Kōkūtai exacted a considerable toll from the enemy and the N1K2-Js of the unit remained the equal of any Allied fighter they encountered until the end.

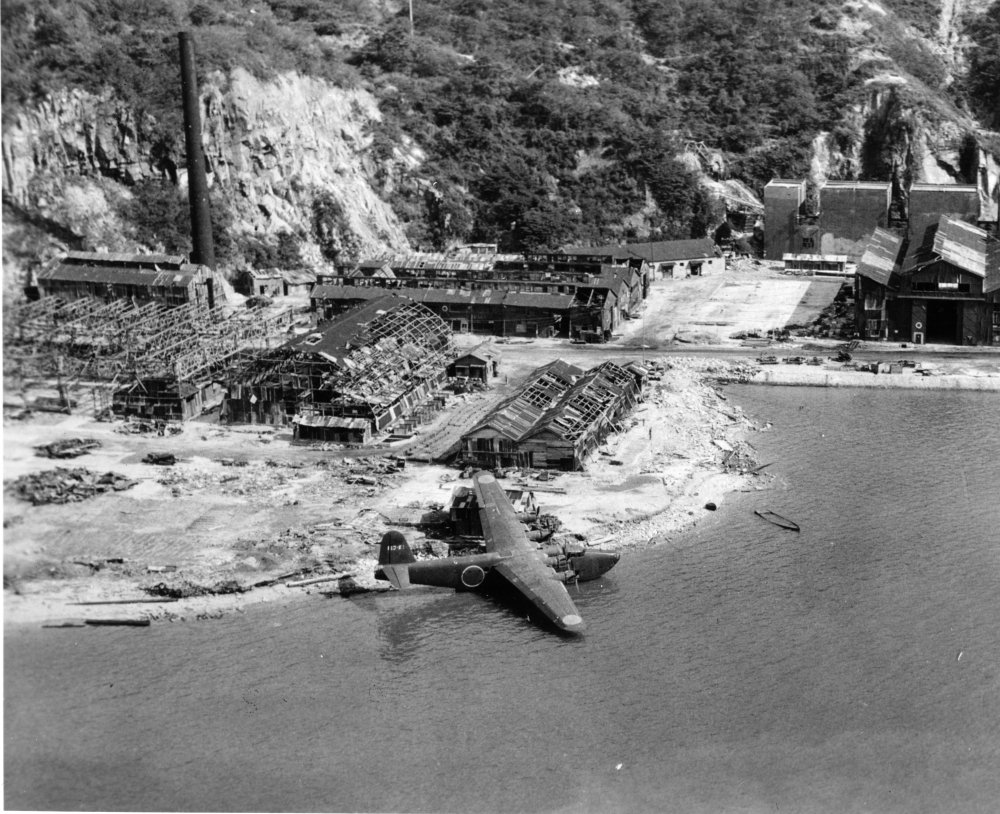

3 Kawanishi H8K

二式飛行艇, Ni-shiki hikōtei (Type 2 Flying Boat)

The Pacific during the Second World War was the largest battlefield in history, yet all but a tiny fraction of it was water. As a direct result the flying boat was of particular value in this huge watery realm, and the best flying boat fielded during the conflict was the Kawanishi H8K, which was the most heavily defended and fastest flying-boat serving with any of the combatants, and remained so until the end of the conflict. In 1929, Kawanishi sent a technical team to the Short Brothers company in the UK, then acknowledged as a world leader in maritime aircraft design (and, perhaps more importantly, a major shareholder in Kawanishi). After building a few examples of the Short Rangoon under licence, Kawanishi mass produced the large and efficient parasol winged H6K which boasted an incredible range, allowing it to undertake unrefueled patrols of up to 24 hours in duration. Unfortunately the H6K was also slow and vulnerable to fighter attack. The H8K was an altogether more formidable machine and represented the greatest technological leap in this kind of aircraft ever achieved.

Designed under a team led by Shizuo Kikuhara, the H8K featured a deep and slender hull and shoulder wing. The hull initially gave serious trouble, the prototype being prone to severe porpoising and the spray thrown up by the bow completely inundated the two inner engines. On one occasion the spray was so bad that the propellers were damaged. Careful redesign, conducted in concert with hydrodynamic scientists from the University of Tokyo eliminated these issues and the H8K’s hull was the most efficient fitted to a flying boat during the war.

As well as performing the same maritime patrol, reconnaissance, and anti-submarine work as contemporary flying boats of other nations, the H8K was also expected to carry out additional offensive tasks as a torpedo carrier and bomber. In the latter role, the H8K was intended to operate in concert with supply ships at which they could refuel and arm, effectively giving them a transoceanic range. The H8K was employed in exactly this fashion in the opening weeks of the war when on 4 March 1942, only a month after it entered service, two H8Ks attempted to bomb Pearl Harbor in a follow up strike after the famous attack in December. Refuelled at sea by two submarines, the flying boats’ target was the oil storage depot at the naval base but cloud cover over the target resulted in the failure of this audacious mission, the bomb load was dropped without being aimed and exploded harmlessly. Nonetheless the H8K’s impressive range allowed it to bomb the United States fleet at Espiritu Santo Island as well as Jaluit Island, the Shortland Islands, and the Phoenix Islands, distances of up to 1,850 km (1,150 miles) and up to 18 hours duration. In addition, reconnaissance missions were undertaken along the Australian west coast, culminating with the bombing of Broome aerodrome by an H8K on 17 August 1943, the aircraft contributed to the sinking of seven US submarines, and it was developed as an effective transport aircraft, though bad luck due to weather struck again when an H8K2-L carrying Vice Admiral Koga Mineichi, Yamamoto’s successor as Commander in Chief of the combined fleet, flew into a typhoon and was never seen again.

Unlike most other Japanese aircraft, the H8K was considered a difficult target for Allied flyers. It was fast (for its size), rugged, well armoured, and well protected possessing a highly innovative fire suppression system for its huge fuel tanks. It was also fearsomely well armed, with the most produced variant, the H8K2, bristling with five(!) 20-mm cannon and five 7.7mm machine guns. Offensive armament was similarly in advance of its peers, the H8K could carry two Type 91 torpedoes or up to 2000 kg of bombs or mines. The only advantage the H8K did not possess however was numbers, production was painfully slow and after B-29 attacks commenced on the Japanese mainland, was dropped completely so that Kawanishi could concentrate on production of the Shiden-Kai fighter. By war’s end only four examples still existed in broadly airworthy condition. One of these was taken to the US where its hull design heavily influenced that of the postwar Martin P5M Marlin, the last US military flying boat. Meanwhile, Kawanishi, prevented from building aircraft by the Allied occupation switched to general engineering, was renamed Shin Meiwa in 1949 (building cars under the Daihatsu name from 1951) and eventually returned to flying boat construction with the PS-1 which entered service in 1971 and flies to this day, a direct successor to the mighty H8K.

2 Nakajima Ki-84

四式戦闘機, Yon-shiki sentō-ki (Type 4 Fighter)

疾風 ‘Hayate’ (Gale)

Built for an offensive that had stalled by the time it appeared, the Ki-84 barely ever fought the kind of campaign that it had been designed for but even during the chaotic conditions attending the death throes of the Empire that created it, the elegant Ki-84 managed to demonstrate a performance that was as good as the world’s best.

The Ki-84 was conceived in the happier times (for Japan) of early 1942. The Japanese Army and Navy and their respective air arms were trouncing any force that attempted to oppose them but the appearance of superior allied fighters was realised to be only a matter of time. The Army’s standard fighter at the time was the Nakajima Ki-43 隼 ‘Hayabusa’ (Peregrine Falcon), officially the 一式戦闘機, ‘Ichi-shiki sentōki’ (Type 1 fighter), an aircraft in the A6M Zero mould, utilising a relatively low powered engine, light structure and low wing loading to deliver almost unbelievable agility at the expense of more or less all other attributes. This had been supplemented by the Nakajima Ki-44 鍾馗 ‘Shoki’ (Demon queller), the 二式単座戦闘機 Ni-shiki sentō-ki (Type 2 fighter), a dedicated interceptor that focussed on maximum speed and dispensed with the fixation on agility displayed by all other Japanese fighter aircraft and was thus regarded as too specialised to be regarded as a successor to the Ki-43. A fighter that combined the best features of both designs was sought and the Ki-84, designed by Yasumi Koyama, was the brilliant result, the finest Japanese fighter aircraft to see service in large numbers during the conflict.

Top Italian aircraft of World War II here

On its combat debut in China during the Japanese offensive of August 1944, the Ki-84 enjoyed a situation that would not be repeated: facing the US 14th Air Force which was critically low on fuel and supplies, the first unit to receive the Hayate was the 22nd Sentai, formed of highly experienced pilots most of whom had been part of the Hayate service trials unit and were therefore well versed in the qualities of their aircraft. The poor build quality that would afflict the Ki-84 later in its career had yet to appear and the aircraft created quite the impression on its foes. Here was an aircraft that displayed all the virtues of earlier Japanese fighters but possessed none of their shortcomings. It was fast, powered by the lusty 18 cylinder Nakajima Homare with water-methanol injection and delivering 2000 hp at take-off; well armed with two 13-mm Ho-103 machine guns in the fuselage and two 20-mm Ho-5 cannon in the wings; tough: featuring self-sealing fuel tanks and armour protection, both previously largely absent from Japanese fighters; and manoeuvrable: on its debut the Ki-84 could outclimb and outmanoeuvre any Allied aircraft then in service. Intended from the outset as a multi-role combat aircraft, the Ki-84 featured hardpoints for up to a 250kg bomb under each wing and was utilised as a highly effective fighter bomber, notably during the fighting in Okinawa.

It couldn’t last of course, Allied bombing and blockades took their toll on Japanese industry and Nakajima was no exception. Forced to rely ever more on unskilled labour such as students (and having been a student, I know the lowly standards, slapdash approach, and desperation that this implies), whilst dealing with an ever lower quality of raw materials and components, the build quality of the beautiful Ki-84 began to suffer. By early 1945, standards were so lax that individual Ki-84s exhibited seriously differing performance. Hydraulics failed, the Homare engine proved troublesome, undercarriage legs even snapped on landing due to incorrectly tempered steel. At the same time, the old story of combat attrition saw the quality of Japan’s fighter pilots inexorably dwindle. Nonetheless, a Ki-84 in decent shape gave even a mediocre pilot a fighting chance against the ever-increasing hordes of excellent Allied aircraft, and at least there were plenty of them: the Hayate was the most numerous Army fighter by early 1945.

Testing of a captured Ki-84 at Wright Field in the USA, highly impressed American pilots and technical staff. Despite noting that “very little effort has been made to make the pilot’s job easy or safe”, the report highlighted the “unusually strong” construction and states “the handling and control characteristics of the aircraft are definitely superior to those of comparable American fighters” concluding that the aircraft “may be compared favourably to the P-51H and P-47N” which is praise indeed given that the P-47N was barely operational before VJ-day and the P-51H failed to enter service before the war’s end, yet the test aircraft was a fairly early Ki-84. Part of the reason for this spectacularly good showing was the superior fuel available to the US testers with a higher octane rating than that the Ki-84 was expected to consume in service. Decent fuel considerably improved performance (the captured example clocked 427 mph at 20,000ft whilst the official Japanese top speed at the same height was 388 mph) and eliminated any concern about the reliability of the Homare engine. Noted British test pilot Eric Brown was similarly impressed, comparing the Ki-84 favourably against the Griffon powered Spitfire Mk XIV and stating it was the finest Japanese aircraft he flew. Had it been available earlier, before the industrial rot set in and all the best pilots were dead, the magnificent Hayate could have been a very significant problem for the Allies indeed.

1 Mitsubishi Ki-46

一〇〇式司令部偵察機, Ichi rei rei-shiki shirei-bu teisatsu-ki (Type 100 Command Reconnaissance Aircraft)

Reconnaissance aircraft seldom get the attention they deserve, performing totally essential work, usually alone and often unarmed. In the Ki-46 the Japanese possessed the world’s finest example of this type of aircraft. As a reconnaissance platform it was unmatched by any other machine until the appearance of the Mosquito and proved maddeningly difficult to intercept throughout the conflict. As late as September 1944, a Spitfire Mk VIII (itself no slouch) required the removal of armour and a pair of machine guns to achieve the performance necessary to effect an interception. According to an oft-repeated claim, the Germans were impressed enough that they attempted to obtain a manufacturing licence (without success), though a reliable original source for this tale remains elusive. If this is true however, it paints the Ki-46 in a remarkable light, for the race-obsessed Nazis to admit that a superior aircraft was built by an ‘inferior’ people was praise indeed. What is not in doubt however, is the fact that the Ki-46 was the only Japanese aircraft deemed of sufficient interest to be sent to the Soviet Air Force technical institute in 1945 for further evaluation. Even the Japanese Navy, who detested the Japanese Army and everything to do with it, were forced to concede that the Ki-46 was superior to any aircraft they themselves possessed and used it for missions over New Guinea and Australia.

Curiously however, the Ki-46 programme started with the decidedly unimpressive Ki-46-I. Despite the Japanese aircraft industry being exceptionally good at streamlining radial engines (and the Ki-46 was possibly the finest exponent of this trend) the Ki 46-I handled poorly, failed to meet performance estimates and was used largely for evaluation and training. An engine change to the Mitsubishi Ha-102 featuring two-stage, two speed supercharging transformed the aircraft and when the Ki-46-II entered service in July 1941 its performance rendered it immune from interception. Throughout 1942 and 43, the Ki-46 swanned about in near perfect safety, with only an occasional unlucky or careless example falling to Allied fighters. The Ki-46-II was built in the greatest numbers of any variant and remained in service until the end of the war by which time its performance advantage had diminished somewhat but was still potent enough to allow it a decent chance of survival in Allied controlled airspace which was more than could be said for most Japanese aircraft from mid-1944 onwards.

The improved Ki-46-III was faster still due to a weight reduction programme, the adoption of more powerful Ha-102 engines with direct fuel injection, and a revised fuselage design resulting in near perfect streamlining. In this form it could achieve a maximum speed a shade over 400 mph. 654 examples of the Ki-46-III were built, a total that would have been higher but the combination of bombing and an earthquake at Mitsubishi’s Nagoya factory crippled production. The development of a replacement aircraft, the Tachikawa Ki-70, resulted in an aircraft with inferior performance and as a result the Ki-46 was improved further to become the turbo-supercharged Ki 46-IV. Although it never entered production due to the difficulty of manufacturing the turbochargers, its performance was incredible: in February 1945 two of the prototypes flew from Peking to Yokota in 3 hours 15 minutes, covering 1,430 miles at an average of 435 mph. By contrast the cruising speed of the contemporary, and much vaunted, Mosquito PR Mk XVI was 318 mph and its absolute maximum 407 mph. Loved by its crews and respected by its enemies, the Ki-46, designer Tumio Kubo’s masterpiece, was for most of the war in a class of its own.

Correction: the initial variant of the Shiden was the N1K1-J, not the N1K-J.

The formidable Mitsubishi Ki-83

キ83 (Ki 83)

Produced by a team under Tomio Kubo, who also designed the superlative Mitsubishi Ki-46, the Ki-83 could have been the finest twin-engined fighter of the war. As things turned out it became an obscure footnote in aviation history.

The result of an Imperial Army specification calling for a high altitude, long-range heavy fighter the aircraft that emerged from Mitsubishi’s experimental workshop was possibly the most aerodynamically clean radial engined aircraft ever built and possessed spectacular performance. As well as recording the highest speed attained by any Japanese aircraft built during the war, the Ki-83 was blessed with remarkable agility for such a large aircraft and was fully aerobatic at high speeds. It is recorded to have been capable of executing a 2200 feet loop at 400 mph in 31 seconds. Compared to its direct US equivalent, the F7F Tigercat which also failed to see meaningful service during the war*, the Ki-83 had the same range but was faster and more manoeuvrable. Armament comprised the potent combination of two 30-mm and two 20-mm cannon, all firing through the nose. Unfortunately for this superlative warplane, its timing was appalling.

First flown in November 1944, tests were often interrupted by American air raids and of the four prototypes known to have been completed, three were damaged or destroyed by bombing. The crippling raids by B-29 Superfortresses were also the reason that the Ki-83 never entered production: despite the enthusiasm of both the Army and Navy, by the time it was flying all aircraft manufacturing was focused on interceptors to combat the B-29 and the Ki-83 never received a production order. After the war the sole surviving prototype was evaluated in the US and received glowing praise. With the higher octane fuel available in America the Ki-83 ultimately recorded a speed of 473 mph. Despite being earmarked for preservation the only Ki-83 to survive the war and arguably the finest wartime fighter produced in Japan was last recorded at Orchard Field Airport in Illinois in 1949. It is presumed to have been scrapped there in 1950.

*The first operational F7F sorties took place on 14 August 1945, the war ended the following day.

From this angle the small window in the fuselage for the optional second crew member is visible just above the tailplane. The outlet at the rear of the nacelle is the turbocharger exhaust.

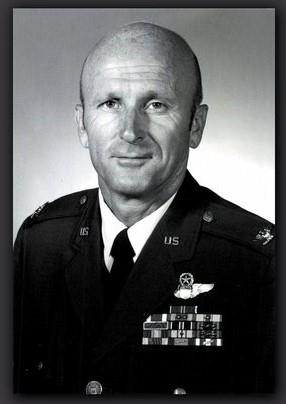

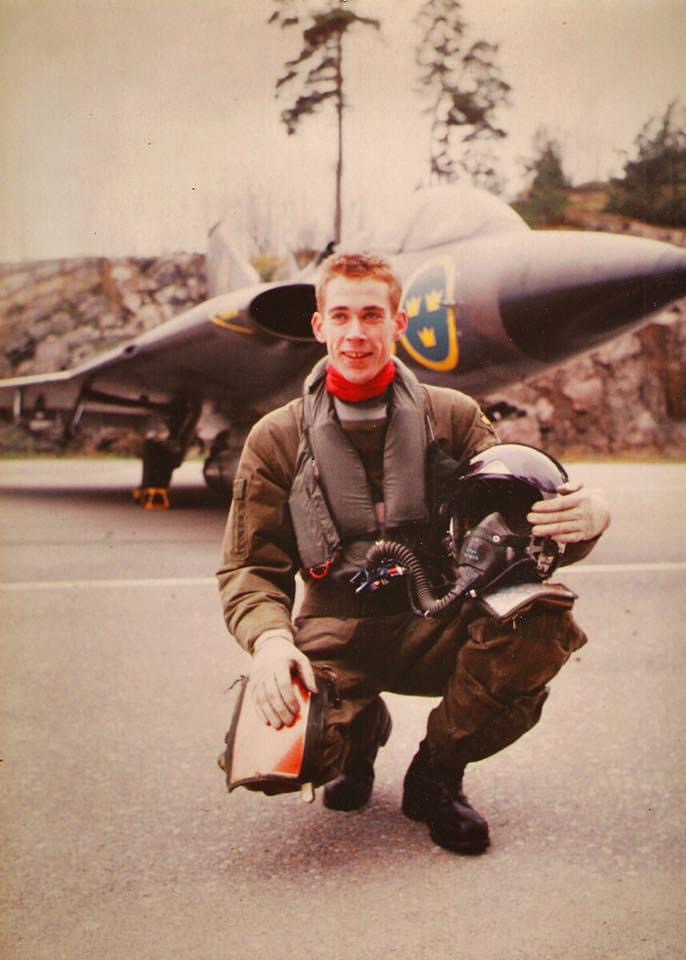

I flew the Danish F-35 Draken

Dirk Reid swapped his RAF Tornado for a Saab Draken in the Royal Danish Air Force. Here he describes the excitement and idiosyncrasies of the fabulous F-35 Delta Dragon.

“It was a single-seat, single-engined aircraft, yet went for 13 years without any hull loss – compare that with Jaguars, Harriers and F-104s.

Draken in three words..

Quirky, innovative, versatile

What was the best thing about the Draken? Adaptability – our roles included recce, anti-shipping, EW, air-ground, other versions were capable air defenders in their time. And the radio, which had hundreds of pre-studded frequencies – just rotate one knob to find the airbase, then press the button marked ‘Radar’ for the radar frequency, the one marked ’Tower’ for the tower frequency etc etc

..and the worst? Being a double delta, it’s low-speed handling. In a stall, the rear section of the wing would lose lift first, whilst the forward part would continue flying, hence the nose came up. Then the forward part lost lift, so the nose would drop, until increased speed caused it (but not the rear part) to fly again, so the nose came up again….. This was called a super-stall, recovery required the stick to be pushed forwards as the nose came down, until both parts of the wing were creating lift, and then pulling out of the subsequent dive – if you had 10,000 ft to play with. Hence the front of the stick was fitted with the ‘knife’, a narrow blade of metal that, when the AoA, or onset of AoA was too high, rapidly vibrated against the pilots fingers causing a natural immediate releasing of the stick. Also, the fuel-state indications in the cockpit, which led directly to the first hull loss for many years. The SAAB designers were very good at taking human qualities into account when developing the aircraft, but this was a rare lapse.

What is the biggest myth about the aircraft? It’s short-field capability. Despite the parachute, landing at Rønne, Bornholm, which was 6,500ft long, needed you to get it on the numbers.

What was your first flight like? Such a long time ago! Thoroughly enjoyable I recall, but a blur of activity with plenty of fuel checks – I was used to turbofans, not a turbojet!

What was your most memorable experience flying the Draken? Probably the long-range recce missions into the far east of the Baltic. We’d launch from Karup and do a training mission on our way to Rønne, where a very lean support operation would give us fuel and a fresh parachute, which we’d have to re-fit into the aircraft. The recce from there was usually a hi-lo-hi profile, with a pair of F-16s as top cover to provide radio relay. We’d do as much as we could before pulling out on fuel minimums for the cruise home with the film for the eagerly-awaiting Photo Interpreters. If we got low on fuel, it was hard to resist the temptation to slow down, which had worked very well on my previous aircraft, but the double delta produced a max range speed of 450kts at low-level or 0.87M at height!

What was the role of the Draken and in which unit did you fly? It had many roles, but 729 Sqn was primarily a recce and anti-shipping outfit. We did a lot of ship recce in the Baltic, the cameras could be mounted to face forwards, sideways, down and rearwards, there was even a 42 inch sideways-facing lens that was very useful for peering deep inland. In the anti-shipping role we weren’t equipped with any guided missiles, so weren’t blue-water capable, more using rockets, bombs and bullets for opposing landing forces.

A. Instantaneous turn rates

Excellent for it’s generation, but no match for an F-16

Sustained turn Needed the burners in! Incidentally, I was used to the Tornado, where the engine ran at max dry and the reheat was varied by the throttle once ‘through the gate’. In the Draken, the burner was on/off, and the engine speed was varied with the throttle

C. Climb rate Good for a mud-mover, but not equal to the fighter versions – we generally carried a lot under our wings.

D. General agility Not brilliant once the speed came off and the double delta started inducing drag.

E. High angle of attack performance See reference to the super stall above

F. Off-base operations Bread and butter to the Swedes, and designed into the airframe, but we never practised it.

G. As a fighter No radar in our version! We practised ACT and did well in a visual fight against older aircraft.

H. Sensors Day VFR only – we had a HUD for weapon aiming and a radalt and a laser to get the data into the weapon-aiming system – all our ordnance required visual acquisition of the target. Ironically, it had brilliant lighting for night close-formation flying, in stark contrast to my previous aircraft, the Tornado – supposedly designed for night flying!

I. In terms of combat effectiveness and survivability? The aircraft was at the end of its life and we retired it from RDAF service when I was there. The Danish were very innovative in terms of the tactics they used, but ultimately the avionics fit limited its capability.

J. Cockpit layout and comfort? Of its day – a scattering of switches and instruments, with a mid-life update thrown in! It was also on the small side, not ideal for an ex prop forward. During landing, aerodynamic braking was normally used, with the aid of the fourth set of wheels in the tail, to slow the aircraft down. There was a radio transmit switch at the rear of the stick which could get involuntarily operated if an excessive belly got in the way, causing much embarrassment.

What should I have asked you? About the safety record. It was a single-seat, single-engined aircraft, yet went for 13 years without any hull loss – compare that with Jaguars, Harriers, F-104s etc.

Did the aircraft have a nickname? It’s called the “Dragon” – no need for a nickname!

Which weapons did you deploy and which was the most spectacular from the cockpit? US dumb bombs, CBUs, cannon and rockets – firing 2 full pods of 2.75 inch rockets was definitely one of my highlights!

Did you fly DACT against types and if so which types and which was the most challenging? Not really, plenty of low-level evasion against RDAF F-16s though.

Do you love the aircraft? Super-reliable and with some outlandish features – what’s not to like?

What was unusual about Danish air force tactics and culture? The culture was very different to the RAF, which consumed all and became a way of life. The RDAF was unionised, worked a set pattern of hours through the week and the workforce scattered to the four winds when the working day had finished. There was a very open and honest culture when it came to safety, which I am sure contributed to the impressive record alluded to earlier. Tactically, they were very free-thinking, willing to innovate and try new ideas.

Dirk Reid/Sqn Ldr/729 Sqn RDAF/1991- 94.

Hush-Kit gives its readers a lot, if you feel this massive effort deserves support then head over to Patreon and subscribe. Grab yourself a copy of the highly acclaimed The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1. Vol 2 can be pre-ordered here.

Winkle: The Extraordinary Life of Britain’s Greatest Pilot

Hush-Kit talks Winkle with Beaver

Captain Eric Melrose ‘Winkle’ Brown is a strong candidate for being the greatest test pilot of the 20th century. Paul Beaver’s forthcoming book takes a look into the psychology of this cool-headed Scottish master pilot and the human story of Winkle’s success. Away from the his undoubted flying brilliance, lurk awkward questions about his thwarted desire to fight on the Fascist side in the Spanish Civil War. We met veteran aviation writer Paul Beaver to find out more.

Who was Eric Brown and why is he important?

Captain Eric Melrose Brown – known to everyone, except his close friends as Winkle was a naval test pilot, squadron and station commander who flew more types, carried out more deck landings and carrier recoveries than one pilot before or since. His record is unlikely to be bettered because there just aren’t the number of types flying. His 487 types logged does not represent marks either – he flew fourteen marks of Spitfire for example.

Winkle is important because he was the greatest handling test pilot of all time. He also mastered difficult machines with skill and still found time to be at important 20th Century events – the Olympics in Berlin, Germany pre-war, the flight of the first jet in Britain, interviewing Gring, identifying Himmler, Bergen-Belsen, and many others. He was friends with statesmen, pilots and industrialists and even called Shirley Bassey and Glenn Miller ‘friends’.

What were his three favourite types and why?

Over forty years of friendship, I chatted to Winkle on numerous occasions about his favourites and least favourites. We draw up a list which is to be in WINKLE – the biography in full. Top Trumps for Eric were (1) de Havilland Sea Hornet which he took to the deck on 16 August 1945 and which he cited as having all the advantages of the Mosquito but very few, if any, of the vices; (2) Messerschmitt Me 262A which had a special place in his heart and which he first flew on 24 June 1945 at Grove in Denmark. He would have been delighted to see the Me 262 at RIAT this year and would still marvel at its advanced wing design; (3) Supermarine Spitfire Mk XIV because of its high tactical Mach number and which he reckoned was the best of the breed. He liked the Mk IX when he flew it in combat, but he rated the Mk XIV as outstanding.

- And three types he didn’t like (and reasons why)

Eric loved aeroplanes and helicopters, he loved flying and testing, but he often said he was lucky to get away with flying some types. His least favourite aeroplanes of all 487 flown were (1) the General Aircraft GAL/56 which said, “don’t come much worse than this one” and another time he told me that flying it was a “battle of wits”; (2) de Havilland DH 108 Swallow, the test pilot killer which cost the lives of two key test pilots between 1946 and 1950. Eric thought he survived flying it in 1948 because of his small stature – hence the nickname Winkle – which meant that his head didn’t hit the canopy in violent oscillations; (3) the Fairey Spearfish which Eric would also reference to me as a “real old cow”.

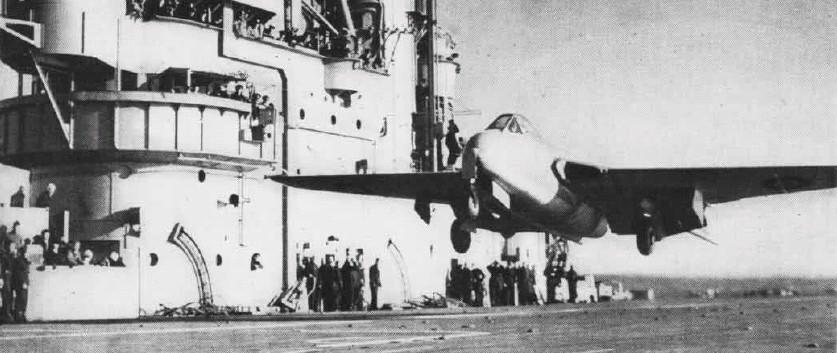

It often said Winkle performed the first twin-engined aircraft take-off from a carrier, yet there is a rival French claim – which is true?

Winkle’s claim holds. The French claim is undocumented and there is no real evidence. Just like the American claim to the first jet landing on a carrier.

What was Winkle’s role in the Spanish civil war? Is it true he said he didn’t mind which side he was fighting for?

In 1945, there is a record of a throw away line from Eric after his jet deck landing aboard HMS Ocean where he admits to the Daily Mail to fighting in the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War. I spent a good few weeks working on this clue and found, in a logbook and from interviewing his other friends that there was something in the story. In the biography WINKLE, I go into detail about the flying experiences he had but caution that there is no passport or other travel evidence to support his claim. In terms of his politics, he had just been in Germany and met pilots of the Condor Legion so his motivation was supporting Franco rather than the Communists. Fate decreed otherwise. His politics were conservative (small c), unionist and Monarchist so not the politics of a socialist who might join the International Brigades which had folded by 1939 anyway. The biography is focussed on Eric’s life and motivations; it’s the man not the machines that will interest the reader.

What was he doing in the Second World War?

Eric’s wartime experiences take up much of the Biography and are too many and too rich in interest to relate in an interview. Read the book! He was commissioned into the Royal Navy, served on a fighting squadron, was torpedoed, became a test pilot, got married, became the wizard of deck landings and flying under bridges, saw combat over Occupied France and commanded the Enemy Aircraft Flight at RAE Farnborough. He took fewer than ten days leave!

What were his experiences of Nazism in the post war German air force?

Eric was essentially non-political. He liked Germany pre-war but had little contact with the Nazi Party until he was arrested by the SD (not the Gestapo) in September 1939. His next encounter was in 1945 when Bergen-Belsen was liberated that April and then leading the aeronautical test flying of the Farren Mission to Germany’ Post-war, he met U-Boats commanders and fighter aces – he loathed the use of Nazi as a shorthand in popular media for everything German during the war. There were no Nazi Bombers, he would say, just German ones, some of which were flown by Party members and many which were not.During Eric’s time as the Head of the British Naval Air Mission to Germany in 1958. Eric and his wife, Lynn, were guests of a German naval club in Kiel. The Browns were horrified to see the Nazi memorabilia and left. The Club was closed down shortly afterwards.

What made him such a good test pilot?

This is the nub of the biography. The Hon Dr Katherine Campbell, the noted psychologist and biographer of her father, Sholto Douglas, and I discussed Eric’s test flying from a medic’s point of view. She reckons, and I agree, that Eric was able to compartmentalise his life when flying. He shut out everything but the task, even on the day his father died and the day his son was born prematurely. Eric also trained for every eventuality and had a plan for every flight, including likely (and unlikely) emergencies. “Know the numbers,” he told me when I started military flying in the Army Air Corps and remember to have two escape routes already in your mind. The rest is covered in the book!

What should I have asked you?

Perhaps about his thoughts of the aircraft which got away: (1) X-15 which he could not fly because of his nationality; (2) the SR-71 because when it came into service, he had retired and (3) the Miles M52, about which I have a different take to the preserved wisdom.*

* I pressed Paul to share his views on the M52 but he refused and instead suggests we learn his views in his forthcoming book

Paul Beaver retired from the British Army Reserve in 2012. He was commissioned into the Army Air Corps (V) in 1987 and ended his career as Colonel (Reserves) in the Joint Helicopter Command. In the intervening period he flew Scout, Squirrel, Gazelle and undertook an Apache course in America in 2009. During various exchanges and visits, Paul flew German, French, Italian, Spanish and US National Guard single-engined types including Mike-model Hueys with the latter.

Hush-Kit gives its readers a lot, if you feel this massive effort deserves support then head over to Patreon and subscribe. Grab yourself a copy of the highly acclaimed The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1. Vol 2 can be pre-ordered here.

IN COMBAT WITH LOCKHEED F-117 NIGHTHAWK PILOT MAJOR ROBERT ‘ROBSON’ DONALDSON

The F-117 Nighthawk was a ‘silver bullet’, able to effortlessly penetrate the best-defended air spaces in the world by virtue of stealth, as first demonstrated to the world during Operation Desert Storm against Iraq. Major Robert ‘Robson’ Donaldson describes taking the stealth fighter to war.

THREE WORDS TO DESCRIBE THE F-117?

Deadly. Stealthy. Mysterious.

THE INVISIBLE MEN

The personality of the pilots chosen was actually a big deal since everyone was handpicked. In peacetime training, we were 200

miles north of Las Vegas at our base on the Tonopah Test Range, Nevada, for four to five days each week, so we all had to get along because we were in this same fishbowl. I think we were all of the same mindset, that even if the mission was a one-way suicide, we would still go. In wartime, I had to trust my fellow pilots with my life, and I did.

MEETING THE GHOST

I first saw the F-117 in a closed hangar at our base in Tonopah. Each jet had its own hangar that was shut closed during daylight hours to hide it from spying eyes and Soviet satellites. I walked into a dark hangar with my escort pilot and then the lights came on. There sat a futuristic spaceship with a large American flag hanging overhead. I was stunned. I thought, That’s not real. . . It must be a mock-up or something! It defied all aviation logic. I went over and touched the jet, and then started asking my escort pilot a lot of questions. We walked around the outside and I asked if I could sit in the cockpit. He said yes so I climbed up the ladder and sat in the seat. It was a very spacious cockpit compared to the F-16, which I had just come from. The stick was in the centre like a conventional fighter cockpit and I could see that the design was ‘hands on throttle and stick’ [HOTAS]. I asked about the various countermeasures the jet carried and his answer to all those questions was: ‘Not needed.’ I then closed the canopy and it felt like I was closing my coffin lid. The visibility out the front was very poor because of the location of the HUD [head-up display], and there was no rearward visibility; the side windows were really the only place to see out (very unlike the almost-unlimited visibility I enjoyed in the F-16). I was not yet in class to learn how to fly and tactically employ the jet, but I was really excited to be a part of the programme and get started learning.

TAKING THE ‘BATPLANE’ TO COMBAT

We had a tremendous amount of confidence in the capability of the jet to slip through the Iraqi integrated air-defence system and

precisely deliver our munitions on target on time. The F-117 had been extensively tested against all aspects of a Soviet IADS[integrated air defence system] in the USA. Also, several times during the Desert Shield build-up we ran multiple F-117s right up to the border with Iraq to see what the Iraqi reaction would be: no response was detected by the assets that collected ELINT [electronic intelligence] so we positively knew we could slip by them undetected. Our only concern as pilots was the ‘golden BB’, a random bullet of AAA [anti-aircraft artillery] that would hit our jet and take us down. With vast amounts of bullets from 23-mm, 37- mm, 57-mm, 85-mm and 100-mm guns, this was a very real danger. Iraq was a fully armed nation and the tremendous amount of AAA shot up was the same on the last night of war as it was on the first night. My most memorable mission during Desert Storm was when I was tasked to destroy two bridges in south-east Iraq, close to the border with Kuwait, in anticipation of the ground-assault phase. The significance of the bridges was obviously the Iraqis’ ability to resupply their troops in Kuwait. After a top-off of fuel from the KC-135 tanker near the Saudi−Iraqi border, I entered Iraq in our ‘stealthed-up mode’ (all external lights off, no comm., no antennae extended). Saddam Hussein had already set the oil wells on fire in Kuwait, so as I approached the area I could see there was a heavy black cloud from those oily fires obscuring the ground. My profile

called for bomb release somewhere around 12,000 feet but since our rules of engagement required a positive identification of the

target, I knew that would not be possible from that altitude. I did not want to return to my base with those two GBU-10 bombs

(2,000 lb each with a laser-guided kit). Knowing the terrain is flat in that area, I decided to descend to get below the oily cloud-layer so as to be able to positively ID the bridges, which were about seven miles apart from each other. I had to get down to about 700 feet above ground level in order to be in the clear. Underneath that black cloud was an absolute Dante’s Inferno scenario – a sight I’ll never forget. I went over my IP [initial point: an easily identifiable feature used as a starting point for the bomb run] and lined up on the first bridge. Visibility was actually quite good because the oily overcast reflected the fires light underneath. I

pushed up the throttles to go as fast as I could and my inertial navigation system had positioned the cross hairs of my laser sight right on the bridge, so visual ID of the target in my cockpit was accomplished. I aimed for the far end of the span on the bridge.

The single bomb released very close to the target and I ripped the throttles to idle to slow my speed so that the laser would not

gimble – low to the ground and fast, the laser would run past the span before my bomb hit, thus rendering it a dumb bomb). Ripping the throttles to idle caused the jet to decelerate so that I had time to keep the laser beam on the span but it also caused my

head to tumble so that I felt like my head was going end-over-end through space. The bomb impacted the bridge and the explosion

caused the span to drop into the river. A nanosecond later I saw on my screen an Iraqi army truck drive off the bridge where the

span had been a moment before. I had no time to process that snapshot as my jet was rocked by the explosion of my own bomb,

turning me about 135 degrees upside down and disengaging the autopilot.

I managed to recover the jet about 400 feet above the ground, climb back up to 700 feet and re-engage the autopilot. The fragmentation envelope of a 2,000 lb bomb is 2,500 feet in all directions upward and to the sides of the impact, so from 700 feet above the ground I was well within the frag envelope of my own bomb. I knew that but had decided to take my chances anyway. Once I was right-side up, I immediately looked at my engines to confirm they were running and to check my fuel status. Both were good so I didn’t think I had fragged myself. So a lot was happening in a very short period of time and now I had to line up on my second bridge, which was rapidly approaching, but this time I knew what to expect. Once again, the deceleration, the tumbling, the explosion, a dropped span, and being blown upside down were all that I had anticipated, only this time I climbed up after I recovered the jet and headed for the air-refuelling point. I carefully looked over the engine instruments and my fuel status, and once again all seemed normal. After I had post-strike air-refuelled, I had about 90 minutes to reflect on that sortie. It was very satisfying to drop those two bridge spans but I wasn’t 100 per cent sure that the Iraqi Army truck driving off the span actually happened or if it was my mind playing tricks on me. I’m also pretty sure that since the bombs I dropped had a slight delay-fuse, the bombs penetrated the concrete and then detonated just under the bridge so that a good portion of the bomb fragments would have been trapped underneath the bridge and not gone up in the air into my jet. I landed back at base and our routine was to look the jet over on the outside after each mission and make sure all was intact. So I told my crew chief I was a bit concerned but we both looked the jet over carefully and did not find any self-inflicted holes. We have a saying in the fighter community that God takes care of dumb farm animals and fighter pilots. I’m not sure which group I’m in! Next was a stop and debrief with our intelligence people to assess the strike via the VHS camera film. Sure enough, right there on film was the Iraqi Army truck driving off the span. All in all, it was a very surreal night and I was happy to finally crawl into bed and let my brain and body get some sleep after a five-and-a-half-hour mission.

Hush-Kit gives its readers a lot, if you feel this massive effort deserves support then head over to Patreon and subscribe. Feel free to order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1. Vol 2 can be pre-ordered here.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 here and Vol 2 here

I flew the B-47 nuclear bomber

The Boeing B-47 Stratojet nuclear bomber first flew in 1947 and changed everything. Though it flew the same year as USAF’s first jet bomber, the North American B-45 Tornado, the B-47 was far superior – and pointed the way to the future. Its influence on later jets cannot be overstated, and every Boeing or Airbus at the airport, as well as the immortal B-52, are descendants of the sleek B-47. Of the 2000+ B-47s built, many were part of LeMay’s Strategic Air Command, the most lethal force in history. Colonel G.Alan Dugard (Retired) flew the B-47 in the 509th Bomb Wing, here he gives the low-down on the bomber that made the modern world, and threatened to destroy it.

Describe the B-47 in three words…

Solid, stable platform.

What was the best thing about the B-47?

Compact, and 360-degree-visibility cockpit

..and the worst?

Location of trim items. Wheel for elevator trim was located right side near the throttle quadrant. Rudder trim back of quadrant.

What is the biggest myth about the aircraft?

Lack of manoeuvrability. You could actually roll the B-47

Did you feel confident that the aircraft would have been survivable in a war?

At the stage I flew it, it had high rate of survivability at low level, not at altitude.

What was your most memorable experience flying the B-47

I was flying a normal night mission, programmed for a KC_135 refuelling near the Canadian border going west a nav-leg and a low-level route down south. We had completed a 35,000-pound offload just south of Cleveland and attained our cruising altitude and started our preparation for the nav leg. The co-pilot had dis-engaged his seat to put the sextant in place. When I felt a grabbing to the right, followed by a sever pull to right and a great flash of light. Looking out to the inboard nacelle the # 4 engine was deteriorating from the explosion and the #5 engine was also on fire. Both engines were shut down. I told the co-pilot to return his seat to the locked position and told our “Forth Man”, seating in the lower aisle to fasten his seat belt. I called Cleveland Center, declaring a “Mayday” and asked for the nearest airfield to land at. Our biggest problem was our gross weight due to max onload of fuel. I was told to proceed to Lockbourne AFB in Ohio and was given a heading to the base. I contacted Approach Control for Lockbourne, told them the situation. I asked them if they had a dump area for my wing tanks and after a pause they said yes, but they would have to evacuate the GCA facility before I could drop the tanks. We were dumping fuel as fast as we could and when arriving at the base were still too heavy to land. We were fairly stable and so decide to just burn down to a landing weight, and still dumping*. As the tips emptied we were at the max weight for landing and made a landing, not the best I ever made, but good enough. Examination of the two engines’ showed extensive damage to both nacelles as well as the engines.

*Some have questioned this, asking if the B-47 was capable of fuel dumping, this may have been misremembered

An interesting second choice:

First deployment over the pond and refuelling with a KC-97 Tanker. The 97 had a ceiling of about 15,000 feet and a speed that was within a marginal point of the B-47 stall speed. It was a clear night at altitude, 28,000 flight level, but the refuelling took place at the tanker’s ceiling, and the tops of the undercast was 17,000 feet. The descent from clear skies to the Tanker was a radar rendezvous in the zero visibility clouds. Format speed was ok at the lock-on to the tanker and visual contact with the tanker was gained at about 30 yards. Contact made was realized with some turbulence, making it difficult. As the fuel was coming in and the B-47 gross weight increased it became increasingly apparent, that we were at a marginal speed. The tanker was forced to start a descent to maintain contact. Offload of 30,000# of fuel was finally made and a disconnect was taken. It was a sweat filled mask as we started our climb back to altitude.

What was the role of the B-47 and in which unit did you fly?

The B-47 was the primary deterrent Nuclear Armed aircraft of the initial “Cold

War. The 509th Bomb Wing (The unit that dropped the atomic bombs on Japan, ending WWII.

How would you rate it in the following categories?

A. Instantaneous turn rates

It was a very responsive aircraft

B. Sustained turn

You had to work at it one hand of the wheel and the other on the trim wheel.

C. Climb rate

Depending on gross weight, but alighter aircraft could put the nose in the air. Heavy your rate of climb was limited.

D. General agility

I liked flying the B-47. It was very responsive due to the sweep wing

E. High angle of attack performance

It flew like a bomber at altitude, but was very agile at low level and during “pop-up” procedures at low level.

F. Bombing accuracy

Excellent bombing platform. Usually highly accurate bomb results, CE below 500 ft

G. Cockpit layout

Nice cockpit, well arranged for flight instruments, gear and flap handles very convenient.

H. Sensors

Chaff and standard Jamming gear.

I In terms of combat effectiveness and survivability?

A very survivable aircraft at low level, Very vulnerable at high altitude.

Cockpit layout and comfort?

It was not intended for long missions, but it would treat you well for seven-eight hours flight.

What should I have asked you?

Emergency bailout for the Radar Navigator was downward and if on-board the forth man exit was out of the RN’s hole.

Thoughts on range and bombload?

In-Flight refuelling made the B-47 a long range bomber and the bomb load varied according to the type of bombs carried, Nulear load was four to six bombs.

Which weapons did you deploy, and which was the most spectacular from the cockpit?

Never dropped a bomb in anger.

Unofficially what’s the fastest and highest and the aircraft was taken?

.95 Mach, 38, maybe 40 K.

Do you love the aircraft?

I felt very at home in the B-47

What was unusual about B-47 tactics and culture?

It was an aircraft built for the typical role of a bomber at high altitude, but evolved into a most effective low altitude penetrator.

What were B-47 pilots most afraid of?

Loss of an outboard engine on takeoff. A number of takeoff accidents for this occurrence happened. Two at my home Base in New Hampshire and others at other locations. It was discovered that the reaction of pilots to this was to use aileron movement to correct the loss of direction control. Photos later discovered the problem was exacerbated by use of aileron and resulted in a situation called “Roll due to Yaw”. Correction of only rudder would correct the roll.

Did B-47 pilots feel about the absence of defensive weapons?

There was a twin 20 mm cannon in the tail controlled by the Co-pilot.

Tell me something I don’t know about the B-47

Although it was built to deliver nuclear weapons, it had the capacity to deliver conventional bombs and missiles.

What was base life like? How did you unwind?

Ideal location for water and mountain sports. Very family oriented, but a very professional group of crew members. The first jet bomber that incorporated the new jet trained pilots into an older group, of prop driven pilots, both learned from the blending.

Hush-Kit gives its readers a lot, if you feel this massive effort deserves support then head over to Patreon and subscribe.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 here and Vol 2 here

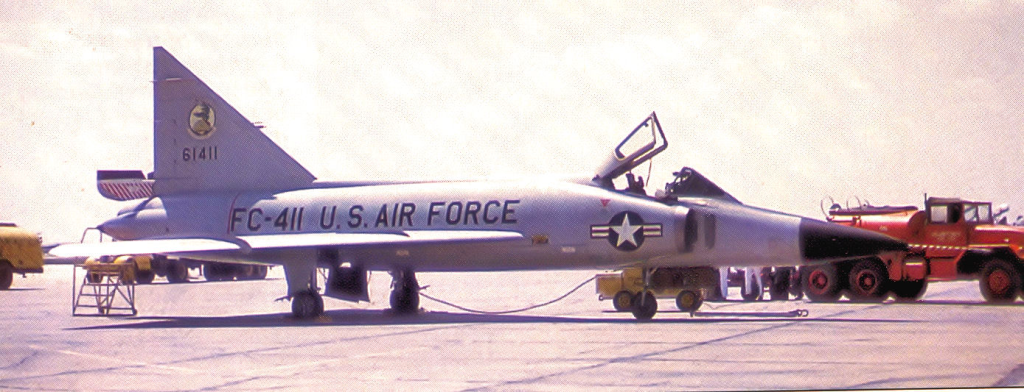

Interview with Convair F-102 Delta Dagger pilot

Deuces Wild!

Incredibly, despite its futuristic appearance, work on the F-102 began in the 1940s. Tasked with intercepting Soviet bombers at a dangerous time in the Cold War, the F-102 was the tip of the spear for the defence of the USA. Colonel Dugard flew the F-102 for the 87th Fighter Interceptor Squadron of USAF in the late 1950s. Here he reviews the flawed but formidable F-102, a vital stepping stone to the excellent F-106.

Describe the F-102 in three words.

Heavy Fighter Aircraft

What was the best thing about the F-102?

Delta Wing gave it great manoeuvrability.

..and the worst?

Heavy detracted from climb response.

What is the biggest myth about the aircraft?

That it was a good air-to-air combat aircraft

How good was as a dogfighter compared to other aircraft?

Could stay in contention if turning, but very vulnerable in climb

What was your most memorable experience flying the F-102?

Flying as a target aircraft for other F-102s. On a night mission with a low overcast and after a couple of intercepts I got a red weapon systems light. I broke off the mission and although not an emergency for flight, called the command post and was told to RTB (return to Base). I proceeded to the fix for a penetration to station. And was told to hold due to traffic in the area. After holding for a substantial period-of-time I was cleared to penetrate. I was placed in the pattern as #3 for landing. I noticed my fuel state was getting low and the yellow fuel-light came on. The fuel counter had not started to click down so I was comfortable with my state. Finally, I was cleared for a GCA approach. On final my fuel counter started to click down and was notified to go-around due to an aircraft problem. As I started my go around, I told them I had a low fuel state. Approach Control acknowledged the call, but then let another aircraft slip in front of me for landing. The RED fuel light game on indicating I could not make a go-around on the next approach. I asked for an immediate clearance to be given a priority approach. Not getting a response I called out “Mayday”, Getting their attention I was placed on final and completed the approach and landing, After clearing the runway and jettisoning my drag chute on the taxiway, the aircraft engine flamed out. I was towed to a parking slot.

What was the role of the F-102 and in which unit did you fly?

Air Defence Command, launched to intercept intruders 87th FIS

How would you rate it in the following categories

A. Instantaneous turn rates.

Good Delta wing, leading to good wrap up 90-degree bank angle turns.

B. Sustained turn

Hold it until you grey- or black out.

C. Climb rate?

Can peg 4k/min with AB to speed drop down.

D. General agility

Heavy fighter, not intended for much more than intercept.

E. High angle of attack performance

Will run out of airspeed with sustained High Angle of attack.

F. As an interceptor

Excellent

G. Cockpit layout

Very pilot friendly cross check for in-flight instruments

H. Sensors

Sensitive of and responsive to the presence of other aircraft.

I. In terms of combat effectiveness and survivability?

Good visibility forward and above. Survivable in its role.

J. Cockpit layout and comfort?

Comfortable, though seat packed chute has lumps.

What should I have asked you?

About how the low ceiling was not the best for an intercept aircraft.

Thoughts on the escape system?

Ejection seats worked every time.

Which weapons did you deploy, and which was the most spectacular from the cockpit?

Missile equipped aircraft. Most release were range released. Never fired at a live target.

Unofficially what’s the fastest and highest and the aircraft was taken?

Never busted Mach 1, but close. 37,000 feet.

Do you love the aircraft?

No, It was serviceable and a good flying machine, but never felt at home in it.

What was unusual about F-102 tactics and culture?

Typical fighter-oriented society. Alert oriented aircraft, called for rapid response and quick engagement.

What were F-102 pilots most afraid of?

Missile malfunctions

Did F-102 pilots feel about the absence of a gun?

We were flying an interceptor, and the weapons we had on alert were very adequate for our mission.

Tell me something I don’t know about the F-102

The ceiling limitations that I mentioned before.

What was base life like? How did you unwind?

Perrin AFB was located close to the big “D” and functions at the club were common.

Hush-Kit gives its readers a lot, if you feel this massive effort deserves support then head over to Patreon and subscribe.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 here and Vol 2 here

It is time you ordered The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1. Vol 2 can be pre-ordered here.

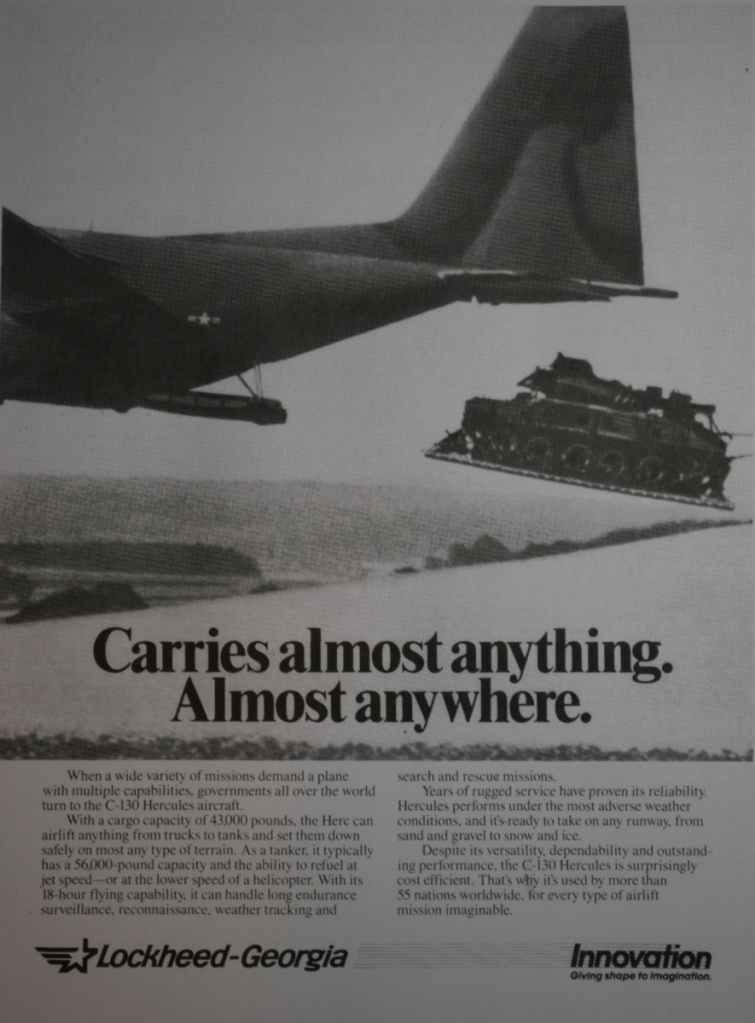

Flying Hercules for the US Coast Guard

Steve Parker doesn’t flew the HC-130 for the U.S. Coast Guard. Here he gives us the low-down on the demanding life of a flying coastguard.

“You have to go out. You don’t have to come back.” That’s not some ooh-rah bullshit. It’s written in blood. It’s written in the blood of my friends.

Describe the HC-130H in three words

I don’t think one can describe the C-130 in three words. I don’t do bumper stickers. How can you describe love or women or anything that forms an important part of your life in just three words?