Category: Uncategorized

Clash of the Cancelled, Round 4: World War II Fighter Aircraft, Heinkel He 100 versus Martin-Baker MB 3

History chewed out and spat out some incredible aeroplanes. We drag these rotting morsels out of the compost mulch of history and drag them to our laboratory/fight-club for autopsy. To assist us in our morbid analysis is Hush-Kit’s tamed scientist and engineer Jim ‘Sonic’ Smith (a key figure in the Typhoon and UK JSF programmes among others). To further our thrills we shall pit these dead aeroplanes against each other!

A pair of particularly neat and tidy high-performance fighters which share many common facets in their development stories. Both were seeking to replace current production aircraft, whose performance they exceeded; both had interesting technical features and were beautifully engineered; and both missed out, largely for reasons of industrial policy in time of war, driven by pressure on the availability of suitable powerplants, and a desire not to disrupt the production of in-service operational aircraft.

“When matched against each other in air combat, the MB 3 pilot would have been well advised to avoid a sustained turning combat, and would instead seek to make slashing attacks, taking advantage of its high speed and heavy firepower to inflict damage without seeking to out-manoeuvre its opponent.”

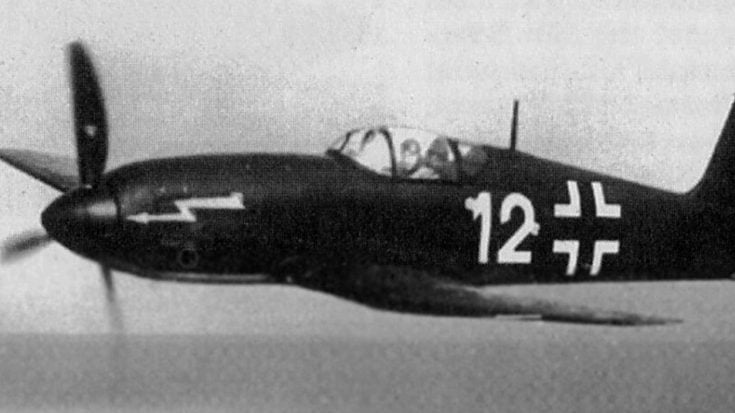

Heinkel He 100

The Heinkel 100 emerged as a result of the Heinkel company’s frustration with losing out to the Messerschmitt Bf 109 in being selected as the Luftwaffe’s single-engine fighter monoplane in 1936. Heinkel’s entry in that competition had been the Heinkel 112. The Messerschmitt design had proven successful largely because it was smaller, lighter, faster, and simpler to build. It did, however, have a few less satisfactory points, with a small, cramped cockpit, narrow track undercarriage and relatively short range.

Following the fighter decision, Heinkel had been advised that they were to concentrate on bomber aircraft, while Messerschmitt concentrated on fighters. However, when the authorities began to consider possible successors to the Bf 109 towards the end of 1937, Ernst Heinkel and Heinrich Hertel did not allow this advice to stand in their way.

Instead, they considered the lessons to be learned from the Heinkel 112, and set out to design a fighter which combined exceptional aerodynamic cleanliness with the simplest and lightest possible structure, while also addressing the perceived shortcomings of the Bf 109. In designing the He 100, they also drew on the experience of the He 119 private venture high-speed reconnaissance aircraft and bomber, designed by Siegfried and Walter Gunter under the guidance of Dipl-Ing Heinrich Hertel.

Our wonderful merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

The He 119 had a number of radical features, including a cooling system which essentially used the structure of the aircraft as a radiator, enabling an exceptionally clean airframe. The cooling system was pressurised, and relied on expansion of the coolant to steam, which was then condensed and returned in liquid form to the engine. The successful application of this so-called ‘evaporative cooling’ system in the He 119 led to its adoption for the Heinkel 100.

The He 100 really was a superbly conceived aircraft, with the lower forward fuselage doubling as the mount for the Daimler-Benz DB601 engine and almost no excrescences to mar the clean lines of the aircraft, apart from a small retractable oil cooler used principally for take-off and climb. This was a result of the use of the evaporative cooling system, which enabled externally mounted radiators to be dispensed with. The aircraft featured a notably roomy cockpit, largely uncluttered by cockpit framing, a wide-track, inward-retracting undercarriage, and a massively simplified structure compared to the He 112.

To further emphasise the performance superiority of the aircraft, the specially prepared V-8 prototype was used to raise the world absolute speed record to 463.92 mph in March 1939. The developed He 100D fighter is stated to have had a maximum speed and range of 416 mph and 553 miles respectively, compared to figures for the Bf 109E (also with the DB 601 engine) of 336 mph and 410 miles.

However, the program did not succeed in winning a Service production order. The reasons for this appear to be hotly debated, but, apart from the policy that Heinkel should build bombers, appear to have revolved around the difficulties Germany was experiencing with producing sufficient DB 601 engines, and maintaining their performance in service. Although Heinkel had been offered the possibility of an order should the He 100 be redesigned to use the Jumo 211 engine, this was not a viable solution, as that engine could not use a pressurised cooling system.

Twelve production series He 100D-1 aircraft were built and eventually used to form a local air defence unit at the Heinkel factory at Marienehe. These aircraft were also used for propaganda purposes, being painted in various unit colours to suggest that significant numbers of the aircraft were in operational service.

Martin-Baker MB 3

The Martin-Baker MB 3 was intended to provide a step forward beyond the performance of the Spitfire and Hurricane, and to exploit the additional power available from the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine. However, that engine experienced a lengthy development, and was not available to the company, who were required to fit a Napier Sabre II engine instead.

The design drew on lessons from the earlier MB 1 and MB 2 aircraft, and combined aerodynamic cleanliness with heavy armament and a sturdy, yet lightweight structure that was designed to be easy to maintain and repair. The engine installation was particularly neat, and the cooling system featured low-profile oil and engine cooling radiators carried under the wings.

The structure featured a steel tube framework carrying light removeable metal panels which provided great access for maintenance while preserving smooth external lines. The wing was built around a strong tapered metal torsion box, built up around a laminated steel spar, and carrying a simple yet robust wide-track undercarriage.

Another feature of the aircraft was the carriage of six 20-mm cannon as armament, enabled to fit in the simple tapered wings by a patented ‘flat-feed’ ammunition stowage system, and designed to be easy to access for both maintenance and re-arming.

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY CLICKING ON THE DONATE BUTTON AT THE TOP OF THIS PAGE. YOUR SUPPORT KEEPS THIS GOING. Thank you.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you.

Development of the aircraft was delayed by the difficulties in engine development, and the original Contract, signed in June 1939, was replaced in August 1940 by a new Contract specifying the use of a Napier Sabre engine. However, the ongoing, and successful, development of other types, notably the Typhoon and Tempest, and the continued development of the Spitfire, had resulted, in late 1941, in a decision that no production order would be placed for the MB 3, although the prototype would still be completed.

The MB 3 had a very short flying career, making its first flight on 31 August 1942, and being destroyed in a fatal accident on its 10th flight on 12 September 1942. In the limited testing that was completed, handling and performance had both been shown to be excellent, with a reported maximum speed of 430 mph being demonstrated. However, the loss of the prototype due to engine failure on take-off, and the death of Company co-founder Captain Valentine Baker in the accident, were heavy blows for the company.

Eventually, the fully-developed, Griffon-engined, Martin-Baker MB 5 emerged, making its first flight on May 23, 1944. Viewed by many as the finest piston-engine fighter ever flown, the aircraft was largely irrelevant, as by then, the focus for future fighter development was on jet propulsion.

Heinkel He 100D and Martin Baker MB 3 – Air Combat Comparison

Having looked at the data for these two aircraft, I was reminded of the contest between the fast, rugged, and well-armed Grumman Hellcat, and the smaller, lighter, more agile, and more fragile Mitsubishi Zero.

Heavily armed, with six cannon, and very robustly constructed, the Martin-Baker MB 3 was more than twice the weight of the Heinkel 100D. As a result, it had a higher wing loading, and, despite having a 2000 hp Napier Sabre engine, a lower power loading than the He 100D. It also had a lower aspect ratio wing, but seems likely to have been slightly faster than the Heinkel.

In favour of the MB 3, however, was its immensely well-engineered airframe, designed to be strong, yet very easy to service, maintain and repair. The other major aspect in favour of the MB 3 was its armament of six 20-mm cannon, compared to the intended one cannon, plus two 7.92 mm machine guns, of the He 100D.

The He 100D offered good speed and manoeuvrability, and might have been expected to be a real handful in turning air combat. However, the key to its performance lay in the evaporative cooling system for the engine, which, although it delivered unmatched aerodynamic cleanness, was also extremely complex and likely to be vulnerable to battle damage.

When matched against each other in air combat, the MB 3 pilot would have been well advised to avoid a sustained turning combat, and would instead seek to make slashing attacks, taking advantage of its high speed and heavy firepower to inflict damage without seeking to out-manoeuvre its opponent. Even if such an engagement could not be avoided, the firepower of the MB 3 greatly outweighed the 3 machine guns actually fitted to the few production He 100D aircraft.

In terms of sortie generation, one suspects the He 100D would have been a nightmare. The complex cooling system required 22 electrical pumps, and these appear to have had a high failure rate. In addition, the system was pressurised and used the wings and parts of the fuselage as cooling surfaces. The system was likely to be very vulnerable to battle damage, as almost any damage to the structure might also damage the engine cooling system.

In contrast, the MB 3 is reported to have had extremely rapid servicing times, due to the provision of many access panels, allowing rapid re-armament and replenishment of fuel and oil. The primary structure was of robust steel tubing, designed to be easy to replace or repair. Sortie generation would be a clear area of advantage for the MB 3.

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY CLICKING ON THE DONATE BUTTON AT THE TOP OF THIS PAGE. YOUR SUPPORT KEEPS THIS GOING. Thank you.

Heinkel He 100 and Martin-Baker MB 3 Assessment

How to compare two aircraft that were brilliant examples of the ‘state of the art’ and yet not wanted by their respective production authorities? Both aircraft had first class aerodynamics, high performance, and good handling qualities. Both aircraft suffered from having the ‘wrong’ engine, in that the DB 601 was not going to be made available for production He 100 aircraft, and the Griffon was never going to be available in time for the MB 3. Both manufacturers were not perceived by the authorities as mainstream fighter designers, and yet both aircraft had also been designed with an eye to significant improvements over the aircraft they were intended to replace.

The case for the He 100 is that it was eventually fully developed, and demonstrated the performance expected from the design. However, one of the key enablers of that performance, the evaporative cooling system, was inextricably linked to the DB601 engine, preventing re-engining with the Jumo 211, which might have won a production order. The cooling system was also very complex, and, as much of the aircraft surface effectively served as a radiator, could have been very vulnerable to battle damage.

The case for the MB 3 rests on its impressive performance and handling, its heavy armament, and the ease of maintenance and repair of its structure. Against this must be set the small size of the Company developing the aircraft, the delays to that development, the unavailability of the Griffon engine, and the disastrous consequences of the failure on take-off of the prototype’s Napier Sabre.

Both aircraft became irrelevant, largely because their competitors came up with first class products to perform the intended role. In Germany’s case, the Focke-Wulf 190, using the BMW 801 radial engine, and in Britain’s case the Hawker Tempest, with the Napier Sabre, and later Bristol Centaurus engine.

So, which was best? Aerodynamically, the Heinkel. Mechanically, the MB 3. A developed six-cannon MB 3 would have been formidable, and the MB 5 gives an indication of where a Griffon engine would have taken the aircraft. For me, the He 100 cooling system, brilliant though it was in enhancing performance, remains an Achilles Heel, as it stifled development opportunity by its linkage to the DB 601, and would probably have been very vulnerable to battle damage. So, by a narrow margin, my choice of better loser goes to the MB 3, even though this was an aircraft which only completed nine successful flights.

An Utterly Adorable Guide to the World’s Cutest Aircraft

Some aircraft are fearsome in appearance, others sexy and some utterly grotesque. Others elicit a more unlikely response from the observer, the desire to protect. Armed only with a teddybear and tiptoeing so as not to wake them we went in search of the 10 cutest aircraft.

Perceiving some animals as ‘cute’ is probably a byproduct of our own maternal and parental instincts, as we tend to see cuteness in animals that resemble human babies. This isn’t even limited to animals – we even see cuteness in machines. When an aeroplane is anthropomorphised its canopy is seen as an eye or face, its nose as a nose and its general proportions are compared to human physiques. Let’s meet the world’s cutest aircraft..

Despite being the most formidable fighter aircraft in the world in 1946, and enjoying a deliciously sinister name, the Vampire could inspire lactation in a three mile radius. Its cute tadpole-like shape, pudgy nose and dimensions tiny enough to be looked down on by a jockey give an utterly false impression of a red-blooded killer.

Yakovlev Yak-14

Nothing in the universe is less cute as an idea than a Soviet battlefield assault aircraft, yet weirdly the Yak-14 glider, which is just such a thing, is adorable. Perhaps it’s the oversized humped cockpit section or the clumsy high sides but we’re desperate to clean that chocolate off its little face and put a plaster on its hurty knee.

Edgley Optica

Curves of some kind are essential for a cute aeroplane and the Optica, Britain’s answer to the unasked question ‘What if we pretended helicopters hadn’t been invented?’, has some darling little curves. The Edgley Optica was probably the most important aircraft in history not to have contributed anything to history. Its cute credentials are somewhat marred by its butch, distinctly agricultural, tail (as with the author).

Antonov An-14

The Antonov An-14 was created by the Soviet Union in an attempt to make the West so brainlessly broody it would renounce capitalism and liberate the proletariat. This didn’t work but the An-14 ‘little bee’ did succeed in winning our hearts. Who’s a good little Antonov? You’re a good little Antonov.

Stits SA-2A Sky Baby

If ownership of a large vehicle belies a smaller penis, then engineer Ray Stits (above) must have been hung like a fucking Blue Steel Vulcan. The minute Sky Baby was surprisingly fast, clocking a somewhat alarming 185mph.

GAF Pika

The GAF Pika was Australia’s daring attempt to see if ‘cute’ could combined with ‘cool’. The result was just cute and Australia gave up the experiment.

Orlican M-2 Skaut

Czechoslovakia spent its brief existence resenting the Soviet Union and making exceptionally cute flying machines, like mummy’s favourite, the M-2 Skaut.

MiG-105

I don’t want to go into space, I want to sit in a high chair and drink apple juice.

Starr Bumblebee II

So cute was the Starr Bumblebee II that was entirely held aloft by aunties pinching its little chubby cheeks.

Colomban Cri-cri

It is not unusual for owners of the French homebuilt Cri-Cri aircraft to keep a one-way baby alarm in the hangar to check if it wakes in the night crying out for oil, fuel or a cuddle. The world’s smallest twin-engined manned aircraft is utterly adorable.

Aero HC-2 Heli Baby

The first and the only Czechoslovakian-designed helicopter to be produced, the HC-2’s engine vibrated at a frequency that caused involuntary ovulation.

According to the Czech proverb ‘Baked pigeons don’t fly into your mouth’ (Pečení holubi nelítají do huby) – indeed they don’t.

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY SUPPORTING US ON PATREON The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you. Our controversial merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

This article was suggested by Hush-Kit patron Chris Williams.

Bell reveals High-Speed VTOL Concept Based on a Folding Tilt-rotor: Our Analysis from Helicopter Expert Dr Ron Smith

Yesterday, Bell Helicopters revealed a futuristic stop-fold aircraft concept combining the advantages of a tilt-rotor with potentially higher top speeds. We consider the proposal with the help of former Head of Future Projects for Westland Helicopters, Dr Ron Smith.

New ideas in rotorcraft technology never die, but sometimes they remain in a state of metaphorical autorotation until the technology reaches appropriate maturity. The tilt-rotor is a very old idea, dating back to the 1909 Dufaux triplane from Switzerland, but it wasn’t until 98 years later that the concept became an operational reality with the V-22 Osprey. Clearly some ideas take a very long time to leave the experimental phase and enter service; Could the same be true of the stowed stop-fold prop rotor? The advantages of tucking away the huge prop-rotors of a tilt-rotor and switching to jet propulsion are obvious, you frontal cross-section is massively reduced and you can potentially break the 540mph barrier that has long limited propeller-powered aeroplanes.

According to Ron Smith, “This concept dates back to 1967 with the Bell Model 627. In 1967 the US Air Force solicited proposals for `low-disc-loading [Vertical Takeoff and Landing] configurations suitable for high-speed flight.’ Bell responded with a proposal for a folding proprotor design. Development and analysis included design studies, leading up to a 1972 test with a full scale 25 foot diameter pylon and rotor assembly wind tunnel in the NASA-Ames Large Scale Wind Tunnel. The original Bell Helicopter proposed stop-fold tiltrotor design allowed for vertical take-off and landing. Take off was followed by a tilt rotor transition sequence rotating the pylon rotor assembly from helicopter to airplane mode, with wing lift supporting the aircraft.

A final conversion sequence involved slowing and then stopping the rotors and folding the blades rearward along the pylon, with propulsion being taken over by direct jet engine thrust.

The Bell Helicopter report of the full-scale blade fold tests (Report D272-099-002, May 1972) is available here.

The images to the left have been extracted from that report and make an interesting comparison with the imagery recently released by Bell.

The current Bell HSVTOL imagery from their recent press release is shown above.

Bell’s press release summarises the capability objectives as follows:

“HSVTOL technology blends the hover capability of a helicopter with the speed, range and survivability features of a fighter aircraft. Bell’s HSVTOL design concepts include the following features:

Low downwash hover capability Jet-like cruise speeds over 400 kts

True runway independence and hover endurance

Scalability to the range of missions from unmanned personnel recovery to tactical mobility

Aircraft gross weights range from 4,000 lbs. to over 100,000 lbs.

Bell’s HSVTOL capability is critical to future mission needs offering a range of aircraft systems with enhanced runway independence, aircraft survivability, mission flexibility and enhanced performance over legacy platforms.

With the convergence of tiltrotor aircraft capabilities, digital flight control advancements and emerging propulsion technologies, Bell is primed to evolve HSVTOL technology for modern military missions to serve the next generation of warfighters.”

The downwash velocity comment depends on the comparison being made. Tilt rotor designs will have higher downwash velocity than a single rotor helicopter at comparable all up weight. They will, however, have greatly reduced downwash compared with jet or fan-lift concepts. There will be drag penalties associated with the rotor and rotor nacelle assemblies, even when folded, but a speed range up to 400 kt seems quite credible.

There is also no fundamental reason why the concept should not be scalable over a wide range of roles and all up weights.

The artists impressions show designs that incorporate some fuselage faceting to reduce radar signature. Despite this, one suspects that real world excrescences associated with blade fold mechanisms will impact both airframe drag and radar signature. The image also shows three different intake arrangements and optimisation of the engine installation will necessarily depend on both radar and IR signature requirements. It is not clear whether an entirely separate propulsion engine is used in addition to a powerplant to provide shaft power to the rotors, or whether a variable cycle engine is proposed that can deliver a controllable mix of jet thrust and shaft power.

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY SUPPORTING US ON PATREON The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you. Our controversial merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

The starting point for a demonstrator would probably avoid the risk and complexity of developing a variable cycle solution simultaneously with a new airframe configuration.

The Bell report from 1972 lists key risks. Not surprisingly, these focus on static and dynamic loads during the blade fold sequence. Having said that, this test programme extended to 40 start / stop transition sequences conducted at full scale in the Ames Wind tunnel. Even though this data was collected some 50 years ago, it does represent (along with more recent experience) a significant contribution to risk reduction.

The risks identified in the 1972 Bell report were (my interpretation of the findings):

• Proprotor instability (alleviated by folding the blades before reaching the high speed flight regime).

• Potentially large amount of blade flapping during the blade fold sequence, requiring flapping restraint and associated dynamic loads. A short duration blade fold sequence would limit the number of cycles to which the system is exposed.

• Dynamic excitation of the wing and pylon structure during the blade fold sequence. During testing, this was found to be associated with blade / wing aerodynamic interference.

• The report also comments that it was found that the mechanisms associated with the folding-proprotor concept are a significant design challenge from the standpoint of achieving a reliable mechanism at a reasonable weight.

All-in-all, Bell Helicopters appear to be well placed to pursue this development. The challenge will be to secure a stable funding stream for the lengthy design and development program that will be involved. The Army is showing sustained interest in high-speed rotorcraft and one imagines that there would be significant interest across the US armed forces in understanding the options to replace the V-22 Osprey.

This could be a starting point and technology demonstration at lower weights could spin off additional applications.

What is the real-world need do you think?

“Bell would say – Civil: executive helicopter replacement (- like the Bell 609 tilt rotor now moved to Leonardo). Air taxi operations?

Military applications – combat search & rescue, special forces, Osprey replacement, armed UAS?”

What are the advantages?

“Primarily speed, possibly manoeuvrability, external noise. (Could be like Osprey – makes the naval fleet operation less vulnerable).”

What are the disadvantages or potential problems?

“Complex transmission and propulsion arrangements, load prediction, certification, failure modes? (but not much worse than tilt-rotor).”

Is it worth the effort?

“Only if there is a genuine requirement backed up by funding / political support and timescales that are achievable.”

What will be the hardest aspect to master if it goes ahead?

“Certification, complexity. Accommodating associated military requirements (crashworthiness? radar & IR signatures, weapon system integration, defensive aids, sensors, operation in adverse environments, survivability, etc.). Weight (issue for anything VTOL), achieving predicted payload and range. Development cost & timescales. (Just like any other military procurement).”

Do you think it will happen?

“Very hard to answer. If it starts to look like a threat to other programmes, their respective protagonists will lobby against it. I can see smaller variants being pursued because something civil might spin off into an armed UAS. Work on smaller platforms will ultimately de-risk more ambitious developments. I’d say less than 50% chance but higher than that for something at the technology demonstrator level with an eye on actual applications.”

Ron Smith

August 2021

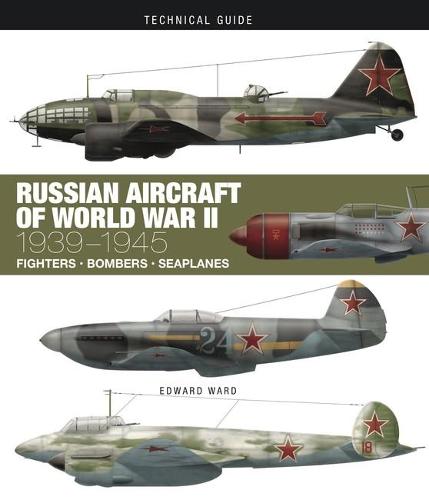

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Soviet World War II Combat Aircraft (but were afraid to ask) with author Edward Ward

Regular Hush-Kit contributor and High Priest of the Cult of the Wyvern, Edward Ward, has written a book on Soviet military aircraft of World War II. We took the time to grill Ed on Soviet warplanes and other perversions.

What is the biggest myth or misconception about Soviet aircraft in WW2?

“There are a few prevalent in the West largely due to the paucity of information available during the Cold war, a time when trashing Soviet engineering in general, even historically, was politically expedient. At the same time, the exploits of Western aircraft in Soviet service was played down by Soviet authorities for exactly the same reason. Subsequently the truth has filtered out but the old myths are stubborn. A good example is that of the P-39 Airacobra, an aircraft rejected from operations by the RAF and unloved by the USAAF. Subsequently palmed off on the USSR, most reference works stated for years that the P-39 found a measure of success over the Eastern Front in the ground attack role due to its heavy armament. We now know that the Airacobra was never employed in ground attack units and was only ever used in the air superiority role, at which it excelled. It was so good in fact that it replaced the Spitfire in service with several units, a fact that would have left British and American pilots aghast. The reason for the disparity in experience was that the P-39 turned out to be, largely by accident, ideally suited to the combat conditions it was committed to. The P-39’s primary failing was that its altitude performance was poor, in the East this was irrelevant as most combat took place at medium and low level and at these altitudes the Airacobra was fast and handled very nicely – it is not a coincidence that a P-39 won the first post-war Thompson Trophy against much more fancied Mustangs, Thunderbolts and Lightnings. It was very reliable and rugged, easy to fly, and its tricycle undercarriage was well suited to the rough fields it had to operate from and Soviet pilots rated it as equivalent or superior to contemporary models of Bf 109 and Fw 190 in aerial combat. Grigory Rechkalov scored 48 of his 54 confirmed ‘kills’ in a P-39, the highest score by any pilot flying a US-built aircraft in the Second World War and its diminutive nickname of Kobrushka ‘Little Cobra’ gives one an inkling of the affection it engendered. None of this was widely known until fairly recently.”

What were the three most important Soviet types and why?

“Difficult to say definitively but I would go for the Yak fighters, the Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik and the Polikarpov U-2/Po-2. The Yaks were the most important Eastern front fighter type, continually improved throughout its life and built in insane numbers (about 40,000). The Il-2 has become emblematic of Soviet air power to the extent that it gave its name to a (very good) Flight Simulator in the 21st century and also serves as the perfect demonstration of the Soviet fixation on air power as a tactical extension of its ground forces. The U-2/Po-2 is the most produced biplane of all time and as well as being a perfectly good trainer and general purpose machine in the mould of the Tiger Moth, more importantly served as the particularly Soviet ‘light nuisance bomber’. A maddening attacker that caused little material damage but was constantly operating over German positions by night, was virtually uninterceptable and impossible to detect coming (approaches were usually made with the engine off and thus in virtual silence). German soldiers could seldom get a good night’s sleep and its psychological effect cannot be overstated. For the chauvinistic German army the fact that many of these terrifying attacks were flown by women was almost unbelievable and led to their nickname of the Nachthexen – Night witches. The Germans also copied the Soviet tactics with their own biplane trainers. Later the same aircraft became notorious as ‘Bedcheck Charlie’ of the Korean War, this time disturbing American sleep.”

How important was the Il-2?

“Simultaneously unbelievably important yet not as important as everyone thought at the time if that isn’t straying too far into cognitive dissonance territory. An Il-2 attack was a terrifying and demoralising experience but much like the Typhoon in the West, its actual destructive effect was overestimated, especially when attacking with rockets. But then, all wartime unguided rockets were appallingly inaccurate. But the Il-2 had a secondary role as a kind of icon – like the Spitfire in Britain, it become symbolic of a specifically Soviet fight back against the invader and as you are probably aware was built in greater numbers than any other combat aircraft in history (sort of – the Yak fighters are all more or less the same but get counted as separate types, if they are all considered the same aircraft then they are the most produced combat aircraft of all time).”

What is the stereotype of Soviet WW2 aircraft and how true is it?

“The Western stereotype is, I suppose, of a badly built, primitive, probably outdated aircraft, likely to achieve success against the much superior German machines only through weight of numbers. This is not true, though like most stereotypes there is a grain of truth at its heart that has been grossly exaggerated. For the fact is that Soviet aircraft, especially early in the war, did lack many refinements common on comparable contemporary aircraft. Early MiG-3s didn’t even have a fuel gauge for example. There has also been a distinct cold war bias when describing the same technology when used by the Russians rather than the Western allies. The use of composite wooden construction on the de Havilland Mosquito for example is generally presented as absolutely fucking mindblowing yet the use of composite wooden construction (for the same reasons) in Soviet fighters especially is usually served up as evidence of their primitive nature. The Lavochkin fighters for example used ‘delta drevesina’, a composite wooden material consisting of layers of birch strip bonded with bakelite film, this material being both appreciably stronger than any untreated wood and fire resistant. Both wing and fuselage were covered with a stressed skin of bakelite ply, minimising the usage of steel and aluminium in the airframe. There was a huge shortage of steel in particular in the USSR in the early war period.”

What was the finest Soviet fighter of the war and how did it compare with its German/Brit/US counterparts?

“It’s a toss-up between the late Yaks and the Lavochkin La-7, given that one of these is a lightweight inline powered fighter and the other a somewhat heavier radial machine, this mirrors the situation in Germany with the Bf 109 and Fw 190 as well as the American P-51 and P-47. There is a general correlation with the dainty Spitfire and heavyweight Typhoon/Tempest as well. Looked at in statistical terms all Soviet fighters were notably smaller and much lighter than their contemporaries, especially the Yaks. Both types were very highly rated for handling both by Soviet pilots and by test pilots from other nations, even the Germans had nice things to say about them in this regard. Performance wise, in say mid 1944, both the La-7 and Yak-3 are beginning to appear in large numbers and compare very favourably with the world’s best. The La-7 manages 423 mph at its best altitude and the Yak 447 mph. By contrast the Tempest V tops out at 427 mph, the Spitfire XIV at 448 mph, the P-47D at 428 mph and the P-51D at 437 mph. On the other side, the 109G-10 is capable of 428 mph and the Fw 190D-9 of 440 mph so everything is in the same sort of area speed wise, although they are all attaining these at different heights. The Tempest was probably the Western Allies best performing fighter at low and medium altitude so is the most directly comparable. The Soviet fighters cannot match the altitude performance of the others but that is irrelevant for their operating environment. In armament terms there is probably the biggest disparity, the La-7 has two 20-mm ShVAK cannon and the Yak-3 just the one, backed up with two 12.7-mm BS machine guns. Soviet fighters always had an armament considered inadequate by other nations. In range performance both the Soviet types lag behind their allies, though the special long-range Yak-9DD was developed for escort duties with a 1300 mile range so it’s not a complete walkover as that’s the same as the operational range of the P-51D (with drop tanks), a fighter known for its long legs.”

What were the biggest strengths and weaknesses of Soviet aircraft designs?

“Like most nations, the Soviets built a range of aircraft that possessed differing strengths and weaknesses but one area in which they lagged somewhat was in engine technology. The Klimov M-105 fitted to all the Yak fighters for example was essentially an outgrowth of the Hispano-Suiza 12Y and its power output was comparatively modest compared to the Merlin, though both started in roughly the same horsepower class, by 1945 the most advanced Klimovs were delivering around 1300hp whilst the Merlin was offering 2000hp or more. Soviet inline engines could never match the reliability of Western engines either due to lesser build quality. The radials were better but as these were all developed out of 1930s American designs (the Shvetsov Ash-82 derives from the Wright Cyclone for example) one can’t help but think they were cheating a bit. By contrast Soviet aerodynamic science was arguably better than that of the West. The USSR never found much use for the P-47s they were sent through lend-lease, regarding it as aerodynamically primitive, but they were astounded by its build quality and the powerplant design was intensively studied. The Soviets were perfectly happy to copy the best bits of other nations aircraft too – they bought a Ju 88 and a Dornier 215 from Germany before Hitler invaded and the Ju 88 in particular considerably influenced the design of the Tu-2.”

Did Soviet aircraft design influence other nations’ aircraft design?

“Not much to be honest. Or at least not directly anyway. The Polikarpov I-16’s impressive showing over Spain could be argued to have spurred the speedy and very successful development of the Messerschmitt 109 but the fact that it was the world’s first low wing, cantilever monoplane with a retractable undercarriage seems to have gone largely unnoticed when it appeared in the early 30s. To be fair, Soviet aircraft didn’t get out much. Later on, the Yak-3 had a sufficiently impressive combat performance to provoke a Luftwaffe general directive to ‘avoid’ combat with it below 5000 metres (which more or less ruled out all combat on the Eastern Front) but the Germans never attempted to emulate the Russian aircraft, even if grudgingly impressed by it. Japan got hold of a LaGG-3 but didn’t think much of it, which was quite reasonable as the LaGG was a pretty terrible aircraft.”

Why was so much fighting at low level on the Eastern Front?

“The simple answer is because neither side was particularly interested in strategic bombing (though both engaged in it a little) and the air war in the East saw the clash of the two greatest tactical air forces the world has ever seen. By contrast, the main thrust of the Allied air effort in the west from the Battle of Britain to D-day was strategic bombing, effective anti aircraft defences had forced bombers to operate higher and higher to survive and therefore it became a relatively high-altitude theatre. But if you look at what the 9th AF and 2 TAF were doing in the west from D-day onwards you see a similar situation emerge as in the East, a lot of low-level tactical short range CAS by fighter bombers and heavy employment of medium bombers. It is no coincidence that the most numerous lend-lease bomber supplied to the Soviets was the Douglas A-20. This wasn’t what planners in the USSR were expecting though, as proved by the large scale production of the MiG-3, a dedicated high-altitude interceptor. The poor old MiG then got itself a pretty poor reputation by being employed almost exclusively in combat at an altitude for which it had not been designed which seems rather unfair.”

How important was Soviet air power to the defeat of Germany?

“The short answer is very. Was it as important as Western air power? Difficult to say. The Eastern Front is generally considered to have absorbed roughly 80% of the German war effort in total but this is not equally distributed amongst the fighting forces. If you look at German aircraft loss statistics, whilst there are peaks and troughs depending on what’s going on at any given time, the general rule is that the losses are split (very) roughly half and half between east and west. The Soviet air force was fighting initially at a qualitative and numerical disadvantage but domestic aircraft production capacity was huge (German intelligence disastrously underestimated it), vast numbers of Western aircraft were supplied to the USSR effectively for free, and aircrew training greatly improved from the dark days of 1941 for the next four years. By 1945 the Red Army was arguably the most effective combined arms fighting force in the world and you can’t deny the devastating effect that air power played in its eventual victory.”

So Russia bombed Berlin? What is the story?

“Just like everyone else in the interwar era, the USSR got simultaneously hugely excited by and terribly worried about the potential of long range bombing. The Soviets developed the impressive Tupolev TB-3 in the early thirties, a strategic bomber ahead of its time but then seemed to largely forget about strategic bombing. The TB-3 was still in service in 1941 but was looking distinctly long in the tooth and the Berlin mission, though well within the range capability of the TB-3 would probably have proved suicidal for the lumbering, fixed-gear Tupolev. It was decided nonetheless that in the first months of the Great Patriotic War that Berlin must be bombed as a morale boosting measure and to prove to the Germans that the Soviets could strike back in response to Luftwaffe bombing of Moscow. Weirdly, the first aircraft to do so were naval Ilyushin DB-3T torpedo bombers of the Red Banner Fleet as the commander of the Soviet naval aviation, S.F. Zhavoronkov, proposed a bombing strike on Berlin and formulated a plan during July 1941. Admiral Kuznetsov approved the plan and on 7 August 1941 fifteen DB-3Ts flew from the Baltic island of Ösel off the Estonian coast. Five aircraft bombed Berlin, the others attacking secondary targets. German radio announced the raid as having been by British aircraft and stated five aircraft had been shot down. In reality none had been lost (one aircraft crashed on landing). Further raids were made over the following weeks and during August the crews of two naval squadrons, made 86 sorties, bombed Berlin 33 times, dropping 311 bombs with a total weight of 36,050 kg. Berlin was visited by the four-engine Pe-8 bomber for the first time on 10 August 1941 and the Soviets regularly bombed the German capital, as well as other cities, for the duration of the war. The loss rate was staggeringly low by contemporary standards – in 1942, one Pe-8 was being lost for every 106 missions (it got worse later) but the numbers of aircraft involved was pathetic, there never being more than 30 operational Pe-8s at any given time and the efforts of the Soviet bombers were essentially unknown in the rest until comparatively recently. The fact that I own a book named ‘The Allied Bomber War 1939-45’ (published 1992) and it does not mention a single Soviet mission or aircraft in any of its 207 pages is fairly indicative.”

What is your fav Soviet aircraft and why?

“It changes on an almost daily basis. However I have always had a penchant for Polikarpov’s fighters. I like rotund aircraft and the I-16, I-15 and I-153 are certainly not sleek. For now I will say the I-153 Chaika. I love that it’s a biplane fighter yet it replaced a monoplane fighter at the front and aesthetically it is unique, a gull-winged, retractable undercarriage biplane which from many angles resembles a barrel.”

Tell us about your book

“It’s a straightforward primer on Soviet aircraft of World War II, part of a series of Technical Guides published by Amber Books, fellow Hush Kit alumnus Thomas Newdick wrote the German entries in the series. I like to think of it as the modern equivalent of those excellent little Salamander Guides in the 1980s. Although it is relatively compact I hope I’ve got some fun nuggets in there, hopefully there’s some aircraft you’ve never heard of (the Shche-2 anyone?) and some surprises: perhaps the world’s first rotorcraft to see combat action? I have also tried to approach every type with an open mind, refer to Russian sources and not just repeat the clichés, fabrications and omissions I read over and over again in the (Western) books of my childhood. Oh and although it’s named ‘Russian Aircraft of World War II’ it is actually Soviet aircraft but the publisher informed me that the word ‘Soviet’ makes people automatically think of the Cold War and who am I to argue?”

What should I have asked you?

“How many Soviet aircraft were designed by people in prison? – the answer is a lot. My next book is on German aircraft of the First World War and it’s surprisingly pleasant not having to deal with designers being thrown in gulags or shot because their aircraft wasn’t immediately perfect.”

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY SUPPORTING US ON PATREON The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you. Our controversial merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

Which aircraft is most like you and why?

“Blackburn Skua: British, mildly interesting in a way, and possessed of much potential in its early days but ultimately flawed, outdated and slow.”

Clash of the cancelled Round 3: Myasishchev M-50 ‘Bounder’ versus North American B-70 Valkyrie

History chewed out and spat out some incredible aeroplanes. We drag these rotting morsels out of the compost mulch of history and drag them to our laboratory/fight-club for autopsy. To assist us in our morbid analysis is Hush-Kit’s tamed scientist and engineer Jim ‘Sonic’ Smith (a key figure in the Typhoon and UK JSF programmes among others). To further our thrills we shall pit these dead aeroplanes against each other!

This comparison showcases two outrageously ambitious supersonic bomber concepts, the US B-70 Valkyrie and the Myasishchev 103-M from the Soviet Union. Designing any long-range aircraft to fly at sustained supersonic speeds is a challenging exercise, and most such aircraft have really been designed with a supersonic dash capability, rather having a long-range supersonic cruise capability. The two aircraft considered here date from the 1960s, with the Myasishchev M-50 having less ambitious performance goals than the XB-70A, which was a bold and unsuccessful attempt to replace the B-52 with an aircraft capable of cruising at Mach 3.

Myasishchev M-50

The M-50 was a delta-winged bomber, which first flew in October 1959. The aircraft caused a sensation with its appearance at the 1961 Soviet Aviation Day fly-past at Tushino. With an approximate loaded weight of 320,000 lb, the M-50 was intended to cruise at subsonic speeds, but was capable of a supersonic dash at speeds up to about Mach 1.5. The propulsion system consisted of four podded engines. The inboard pair were mounted on pylons at about the mid-point of each wing, and were fitted with afterburners. The outer pair of engines had no afterburners, and were carried on the extreme wing tip.

The aircraft had a delta wing and a low-set tailplane which have been described as generically similar to a scaled-up MiG 21. While this may be true for the planform shapes, the overall appearance is quite different, and extremely imposing, and ‘futuristic giant bomber’ is what springs to mind.

While appearing extremely spectacular, the M-50 was intended to be further developed into service, the production version to be the Myasishchev M-52. The various reference sources available quote a wide variety of performance figures, but, as it is believed the prototype made only 19 flights, I would conclude that performance was disappointing. This would have been at least partly due to the unavailability of the 40,765 lb thrust Zubets RD-16 engines proposed for the production aircraft, and their substitution with Dobrynin RD-7 engines of 35,275 lb thrust (afterburning) and 20,945 lb thrust (dry).

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY SUPPORTING US ON PATREON The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you. Our controversial merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

The M-50/M-52 programme was cancelled, with the Tushino appearance of the aircraft in 1962 being the final flight of the M-50 prototype, and the M-52 not proceeding to flight test. As with most of the major powers, a combination of issues, including the vulnerability of manned strategic bombers; advances in the capability of ballistic missiles; and the development of submarine-based nuclear deterrent strategies lead to the cancellation of the programme.

North American XB-70A Valkyrie

Even today, nearly 60 years after the first flight of the Valkyrie, on Sept 21, 1964, the performance aspirations for the aircraft seem incredible. The intention was to replace the B-52 with an aircraft cruising at Mach 3.0 at 70 – 80,000 ft with an unrefuelled range of 7500 miles. The airframe to deliver this performance was an astonishingly beautiful slender canard delta, powered by no less than 6 General Electric YJ-93 engines, each delivering about 19,500 lb thrust dry, or 31,000 lb in afterburner.

The engines were carried in a wedge-shaped common nacelle forming the fuselage below the wing, while above the wing a slender circular fuselage extended ahead of the wing, carrying the crew compartment and canard. The lower fuselage was shaped so that, in combination with the folded down outer wing, lift could be gained through the shockwaves generated by the aircraft at its Mach 3.0 cruise speed. This arrangement also reduced trim drag, and increased lateral and directional stability at high speed. The wing planform was a pure triangle, with 65 ½ degrees leading edge sweep and a straight trailing edge.

Because of the high cruise speed envisaged for the aircraft, the structure of the Valkyrie was largely stainless steel, with extensive use of honeycomb panels, and some use of titanium. Stainless steel honeycomb structures have proved to be troublesome in other applications, and significant electrolytic corrosion was found at a late stage in the construction of the first aircraft, requiring a partial re-build.

During the development of the aircraft, parallel developments in Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) technology and concerns about the effectiveness of surface to air missiles against even the fast and high-flying XB-70A, resulted in President Kennedy declaring in March 1961 that America’s forthcoming missile capability “makes unnecessary and economically unjustifiable the development of the B-70 as a weapon system at this time”. The effort was reduced to two aircraft, which would deliver a programme of research into high-speed flight, and would retain a capability to be developed as a weapon system if necessary.

The aircraft proved capable of achieving its design cruise speed of Mach 3.0, although the lateral and directional behaviour of the first aircraft was unsatisfactory at high speed, and it was eventually limited to a maximum speed of Mach 2.5. The second aircraft was built with a dihedral of 5 deg rather than the slight anhedral of the first aircraft, and this change resolved the high-speed stability problems. Unfortunately, the second aircraft was lost in a mid-air collision on 8 June 1966.

Myasishchev M-50 ‘Bounder’ and North American XB-70A Valkyrie Assessment

Two spectacular-looking supersonic bombers, one Soviet, one American. Both aircraft were ultimately unsuccessful in being developed into operationally useful capability, with the M-50 making only 19 flights, and the XB-70A requiring significant redesign to cure lateral-directional stability issues.

No air combat comparison is presented. The M-50 appears to have been a failure. The XB-70A demonstrated very impressive high-speed cruise capability, but was not developed as a weapon system.

That said, it is an easy decision to make on which of these was the better aircraft. The M-50 never got to fly with the planned production engine, and some reports question whether it was even able to fly at supersonic speeds. The XB-70A was able to demonstrate sustained flight at just over Mach 3, and performed valuable service for NASA in aerodynamic and sonic boom trials.

Both aircraft looked extremely futuristic, and particularly impressive in flight, but the XB-70A Valkyrie gets my vote as the better loser, as it came much closer to its design objectives. The requirements for both aircraft were essentially overtaken by events, as their intended strategic nuclear strike role passed into the realm of the ICBM, whether land-based or submarine-launched.

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY SUPPORTING US ON PATREON The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you. Our controversial merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

Five Fun Vaguely Flight-Related Facts about Ascension Island with author Oliver Harris

Having spent the last couple of years writing a spy thriller set on Ascension Island I was interested to see this mysterious bit of British volcano surfacing in the news recently, once as a place the Home Secretary thought might be good to send asylum seekers, once turning up on the UK’s Green List of holiday destinations that required no quarantine.

Those who explored it as an option for a getaway might have been disappointed. An eight square mile lump of rock in the South Atlantic, halfway between Brazil and Angola, Ascension is one of the most remote islands in the world. Anyone researching their trip to its beaches would have seen that it contains a lot of satellite dishes, a golf course made of ash, two military bases (US and UK) and a village with a school and convenience store. But they’d also learn that potholes on the runway have meant that all MOD flights from Brize Norton (previously the only straightforward way to reach the place) have been suspended for the past four years, and you now need to get three flights in each direction (available once a month), or buy yourself a yacht. You also need permission from the island’s Administrator to stay there. And the only hotel has recently closed down. All of which provokes the question: what’s there? And why?

It was this enigmatic oddness that me think it would be a great setting for a novel (Ascension, pub. this month by Little, Brown). In the name of plugging it to the esteemed readers of Hush Kit, I present five vaguely flight-related nuggets about the island.

1. The name refers to the flight of Christ

Although the island was first discovered by the Portuguese in 1501, it was so unappealingly barren that no one bothered to pass on the news, which meant it had be re-discovered two years later by the naval officer Afonso de Albuquerque who spied it on Ascension Day, the church feast day that celebrates Jesus flying up into Heaven after his resurrection.

It was still too unappealing to claim, though. No one wanted it until 1815, when the British came along, having incarcerated Napoleon on St Helena a few hundred miles away. A small British naval garrison was stationed on Ascension to deny it to the French. For administrative reasons, the island was classified as a stone ship – ‘HMS Ascension’ – to be operated at the discretion of the Admiralty. This made the commandant of the island technically a ship’s captain, with all the legal powers that the role implies. Every child born on Ascension from 1815 to 1922 was officially recognized as having been born at sea.

2. The US built the runway incredibly fast

During the Second World War, it was decided that an airfield on Ascension would be a good idea. The US and UK settled on a location in the south-west of the island named Wideawake Field after the numerous sooty terns (also known as wideawake birds) that inhabited the area.

The U.S. Army’s 38th Engineer Combat Regiment arrived in March 1942 and spent the first 27 days unloading 8000 tons of equipment they had brought with them. A lack of sand and stone to make cement meant they had to use volcanic ash mixed with sea water and bird droppings. The operation proceeded 24/7, with soldiers working under camouflaged lighting systems at night so as to shield their activity from enemy ships.

The runway – 6,000 feet long and 150 feet wide – was completed in just 91 days. Its first visitor was an American Consolidated B-24 Liberator by the name of Our Kissin’ Cousin en route to Natal (in South Africa) from Accra in Ghana. As a refuelling station, Wideawake Airfield facilitated indispensable aviation support for British troops in North Africa when Rommel was launching his offensive on Cairo. It also provided a base for anti-submarine raids, sinking numerous German U-boats and dampening Axis naval pursuits in the South Atlantic. One of the biggest dangers, however, involved the wideawakes themselves. Pilots had to take caution when landing and taking off, as birds could get caught in aircraft engines or break a window. During the height of their breeding season, the airfield had to shut down.

3. Birds on Ascension

The island provides one of the most important homes in the South Atlantic for several species, including the sooty tern, the red-footed booby and the Ascension Island frigatebird, but things haven’t always been easy for its feathered population. In 1815, the British introduced cats to sort out a rodent crisis arising from rats that had got aboard from ships in the early days. But the cats were far more tempted by the seabirds, and soon the bird population had been decimated, with survivors only hanging on in cat-inaccessible locations. In 2000, a project to eradicate feral cats from the island was begun (using traps and cages) and within two years they’d been largely destroyed. So had 38% of the domestic cat population, causing some public consternation. But all in all it was a happy ending, and five seabird species have now recolonized the mainland. The wellbeing of the rats remains unknown.

4. Falklands usage

On 5 April 1982, Nimrods were deployed to Wideawake airfield to support the war against the Argentinians, first being used to fly local patrols against potential Argentine attacks, and to escort the British Task Force as it sailed south towards the Falklands, then as communications relay support for the Operation Black Buck bombing raids.

Operations Black Buck 1 to 7 involved extremely long-range ground attack missions by RAF Vulcan bombers against Port Stanley Airport in the Falkland Islands, then occupied by the Argentinians. The raids, at almost 6,600 nautical miles (12,200 km) and 16 hours for the return journey, were the longest-ranged bombing raids in history at that time.

Because the Vulcan was designed for medium-range missions in Europe it lacked the range to fly to the Falklands without refuelling several times. The RAF’s tanker planes were mostly converted Handley Page Victor bombers with similar range, more often seen refuelling fighters scrambled in response to incursions into British airspace by bombers from the Soviet Union, so they too had to be refuelled in the air, involving relays of aircraft. A total of eleven tankers were required for two Vulcans (one primary and one reserve), which would have been an impressive logistical effort even if they hadn’t all been sharing the same runway.

In the end, the raids had minimal impact on Port Stanley airport, and the damage to Argentine radars was quickly repaired. It has been suggested that the RAF wanted to be involved in the conflict as a guard against further budget cuts.

5. Spaceflight

Although the US initially abandoned the airfield at the end of the Second World War, they returned in 1956. The runway was lengthened and widened to allow for larger aircraft, and later to provide emergency landing for the Space Shuttle. At the time, it was the world’s longest airport runway.

This was just the start of Ascension’s role in the space program, though. In 1967, NASA established a tracking station for Apollo and other spaceflights in a remote area of the island known as Devil’s Ashpit. There are rumours suggesting that the island was used for training the astronauts as well – getting them used to isolation – and even that its surreal rockscape served as the backdrop for a faked moon landing. While these remain unconfirmed, it’s a matter of record that the Devil’s Ashpit station was the first on earth to receive the words: ‘The Eagle has landed.’

NASA staff kept a pet donkey named J.J. outside the operations building, a descendant of donkeys left on the island by Portuguese sailors two centuries earlier. ‘She was there at the tracking station to greet us every morning,’ Harry Turner, a data and antenna programmer wrote in 2003. “We were in the middle of the Apollo 11 mission and we lost all hydraulics to our antenna, meaning that within a short time we would lose the signal from the spacecraft. We ran out to the antenna and found that J.J. had backed her butt into the emergency stop switch.’

Ascension’s remote location continues to make it a good place to keep an eye on things up above us. The new US Space Force has a unit on the island, operating a Meter-Class Autonomous Telescope as part of a space surveillance system for tracking orbital debris (amongst other things?). They also use the Global Positioning System monitoring site at Ascension, which involves one of the four dedicated ground antennas that GPS relies on (the others are on Diego Garcia, Kwajalein (Marshall Islands), and at Cape Canaveral). Meanwhile, post-Brexit, the two European Space Agency Galileo Sensor Stations located on the Falklands and Ascension Island are being removed. The stations host cryptographic material which, in accordance with the EU security rules, can’t be located in non-EU territory.

All of which makes for an odd moment in the history of this British lump of lava. Will it end up in US hands entirely? Is it already? Is the long-overdue repair to the runway connected to plans for a new spaceplane? Or a desire to keep the island inaccessible? Any attempts to put the island’s business on a more democratic footing – for example, by granting citizenship to some of its more longstanding residents – have been quashed. Half a millennia after its discovery, Ascension remains as mysterious as ever, just a lot more busy.

Ascension by Oliver Harris is published by Little, Brown on July 15 (and by HMH Books in the US on the same date).

Ascension by Oliver Harris | Hachette UK (littlebrown.co.uk)

Clash of the cancelled Round 2: North American YF-107A versus Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III

History chewed out and spat out some incredible aeroplanes. We drag these rotting morsels out of the compost mulch of history and drag them to our laboratory/fight-club for autopsy. To assist us in our morbid analysis is Hush-Kit’s tamed scientist and engineer Jim ‘Sonic’ Smith (a key figure in the Typhoon and UK JSF programmes among others). To further our thrills we shall pit these dead aeroplanes against each other!

What a fabulous pair of aircraft these are. The souped-up F-100 development chasing a requirement eventually won by the F-105 Thunderchief, and the Crusader on steroids that eventually lost out to the F-4 Phantom II. The thing that grabs you about both aircraft is simply the look. The YF-107A with its ‘over the top’ variable ramp supersonic intake and recessed, nuclear-capable, weapons bay, and the Crusader 3 with its shark-mouth intake and large twin dorsal fins, which had to be folded up to the horizontal for a successful landing. Just Wow!

North American YF-107A

The YF-107A was a development of North American’s successful F-100 Super Sabre, intended to be a versatile fighter bomber aircraft, capable of missions ranging from air defence to nuclear strike. Initial development centred on a design with a chin intake, like that of the F-8 Crusader, to accommodate a nose mounted radar. This was later changed to the signature dorsal intake design when the Air Force indicated a desire that the aircraft be capable of delivering a tactical nuclear weapon.

Other innovative features of the design included an all-moving fin for yaw control, as used later, on the A-5 Vigilante, and a supersonic variable area inlet duct, later used on the XB-70. Although the wing planform was essentially the same as the F-100, roll control dispensed with ailerons, and used spoilers instead. The 16, 950 lb thrust J-57 engine of the Super Sabre, was replaced by a more powerful 24,500 lb thrust J-75 engine, and the YF-107A was able to demonstrate a maximum speed of Mach 2.0.

The aircraft was armed with 4 20mm cannon, and could also carry up to 10,000 lb of external stores. Following completion of its flight test program, the Air Force conducted a fly-off between the YF-107A and the Republic F-105 Thunderchief, which was narrowly won by the latter. The F-105 was a bigger, heavier aircraft, almost equally dramatic in appearance, which after a difficult development period went on to a long and distinguished career with the USAF. Its particular forte, towards the end of its USAF career, was serving in a SEAD (Suppression of Enemy Air Defences) role as a ‘Wild Weasel’ in the Vietnam war.

Vought XF8U-3 Crusader III

In the mid-1950s, the F8U Crusader had been successful in a US Navy competition for a supersonic shipboard fighter. McDonnell’s proposal in that competition did not make the short list for selection. Displeased by this, McDonnell proposed to the Navy a highly capable twin-engine attack aircraft, the AH-1. In parallel, Vought proposed to the Navy a follow-on development of the F8U, designed around a single J-75 engine, the XF8U-3 Crusader 3.

The Crusader 3 was projected to deliver Mach 2.3+ capability, and would be armed with 4 x 20 mm cannon and 3 air-to-air missiles. The US Navy looked favourably on this proposal, and ordered five prototypes, the first of which flew on June 2, 1958.

h

Meanwhile, the US Navy had indicated to McDonnell-Douglas that they were no longer interested in the AH-1, but (influenced by the XF8U-3 proposal) were now looking for 2-seat long-range all-weather interceptor to be armed only with air-to-air missiles, targeted using the aircraft’s radar system. This aircraft was to be designated the F4H-1, and made its first flight on May 24, 1958.

The US Navy was now in a position to choose between the fast, manoeuvrable, F8U-3 single-seat, single-engine interceptor, and the larger and heavier McDonnell F4H, with two engines, two crew, all-weather radar, and missile armament.

By the end of 1958, the Navy had selected the McDonnell F4H Phantom II, and over years of development and service with many air arms, this proved to be one of the greatest Naval aircraft of all time. The relatively large, low aspect ratio wing of the Phantom, coupled with its twin J79 engines, provided a capable and versatile platform, and the aircraft is still in service today in small numbers.

What of the Super Crusader? Well, the performance of the aircraft as a Naval interceptor was probably unmatched in terms of speed and handling qualities, but compared to the Phantom, it was disadvantaged by having a less capable weapons system, and by being a single-seat, single-engine configuration. The maximum speeds claimed for the XF8U-3 vary, but the aircraft was capable of at least Mach 2.3, and had outstanding manoeuvrability. One of the most distinctive features of the Crusader 3 was the large twin ventral fins carried under the rear fuselage. These were linked to the undercarriage, so that they were deployed downward when the undercarriage was up, and retracted to a horizontal position when the undercarriage was lowered for landing.

The 5 aircraft built were transferred to NASA, and operated from Patuxent River, where they were said to have routinely defeated USN Phantoms in mock dogfights, to the annoyance of the USN.

YF-107A and XF8U-3

Two sensational-looking aircraft, which eventually lost out to two outstanding and versatile competitors, the F-105 Thunderchief and the F4H Phantom II.

The YF-107A and the XF8U-3 were both more manoeuvrable than the aircraft which were favoured with production orders, but the latter proved to be versatile, capable, and impressive performers with long service lives. Both the F-105 and the Phantom II were eventually used in roles which had not been envisaged in their design, and the Phantom, in particular, made a rare, and successful transition for a Naval aircraft, to serve not only with the USAF, but many other land-based air arms.

Both the YF-107A, with its dorsal intake, and the XF8U-3 with its shark-mouth intake and retractable ventral fins, appeared futuristic. Both succeeded in meeting their design objectives and were flown successfully, and both missed out in the procurement game to worthy competitors.

It is really difficult to pick between these two spectacular and relatively successful designs, neither of which ever made it into service. The YF-107A might well have been a better fighter than the F-105, but the F-105 later excelled as a heavy strike aircraft and made the SEAD role a speciality. Similarly, the XF8U-3 was a better within-visual-range fighter than the A4H, but lacked the all-weather capability and versatility of the latter. My choice goes to the XF8U-3 Crusader 3 as the better loser, but this is a judgement based on aesthetics rather than analysis.

North American YF-107A and Vought XF8U-3 – Air Combat Comparison

These aircraft were designed to quite different requirements. The XF8U-3, although only really a day fighter, was heavily armed, with 4 20 mm cannon and 3 air-to-air missiles. It was also very fast, at Mach 2.3+, had a lower wing loading than the YF-107A, and a greater thrust to weight ratio.

The YF-107A was intended to have greater flexibility, and, indeed, to have a tactical nuclear strike capability. It lacked the missile armament of the XF8U-3, but had the same cannon armament, and would also have been a fast and manoeuvrable aircraft, although not to the same degree as the XF8U-3.

In air-to-air combat, the XF8U-3 would be expected to have the edge in sustained and instantaneous turn rate, and in energy manoeuvrability. It would also, in principle, have been able to engage at greater range using its air-to-air missiles.

On sortie generation, there seems little to choose between the aircraft, which both used variants of the same engine. The folding ventral fins of the XF8U-3 are an additional element, but this might be offset by the slightly more difficult to access engine of the F-107.

KEEP THIS SITE GOING BY SUPPORTING US ON PATREON The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here. Thank you. Our controversial merchandise shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

What we know about Russia’s new ‘Fleabag’ stealth fighter: Sukhoi Checkmate Q&A with RUSI Thinktank’s Justin Bronk & update from Jim ‘Sonic’ Smith

Russia reveals what is described as a prototype of a new fighter aircraft at the MAKS 21 airshow. We caught up with Justin Bronk (Research Fellow at the RUSI think-tank and Editor of RUSI Defence Systems) to find out more

Is the Checkmate at MAKS a mock-up or aircraft?

Without higher resolution images it is difficult to be certain. However, the lack of wiring and hydraulic lines within the visible parts of the main landing gear well, as well as the rather oversimplified external textures seen in the leaked footage pre-official the unveiling appear to suggest a mock up rather than a functioning aircraft.

What does the configuration reveal about the aircraft’s role and capabilities?

The Light Tactical Aircraft (LTA) designation and the configuration show that this is clearly a concept aimed at producing a relatively cheap and cheerful, somewhat low observable light fighter, primarily for the export market.

The relatively compact size and engine/intake placement will limit the space available for internal weapon bays. I would guess two IR dogfight missiles in the small side-mounted bays ahead of the main landing gear, and space for 2-4 R-77 class BVR missiles in a ventral bay. However, larger air-to-air and air-to-ground ordinance would likely have to be carried externally. It is also likely to have a modest range with internal fuel due to the competing demands for landing gear housing, weapons bays and avionics within a compact airframe.

As with the Su-57, the LTA features an Infra-Red Scan and Track (IRST) sensor embedded at the junction between the forward canopy and the nose, and will likely feature an active electronically scanned array (AESA) type radar in the nose. The latter, however, will be limited in size due to the narrow and aggressively tapered nose profile.

One particularly notable feature is the lack of conventional elevators. Instead, the LTA has canted stabilisers which are more vertical than I would have expected if a ruddervator (or V-Tail) configuration was intended to provide primary pitch authority. Instead, it would appear that pitch authority will be provided by a combination of tailless delta style elevon control and at least 2D thrust-vectoring. This suggests to me that the LTA has a lessened design emphasis on supermanoeuvrability than previous Russian fighter designs.

How far is Russia from an operational Checkmate?

I would suggest that this is a long way from an operational aircraft. The slick PR campaign and dramatic reveal at MAKS is obviously an attempt to convince some of the nations mentioned in the Rostek commercial to buy into a nascent development programme. The slow development pace and limited procurement scale of the Su-57 Felon (which is far more important to Russia’s own defence needs) shows the limits of UAC’s ability to develop the LTA to an operational aircraft without significant external funding.

Will it be used domestically? How will it aid the Su-57 force and what would it replace?

The Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) tend to purchase a range of different combat aircraft at a small scale to keep the various formerly Sukhoi and Mikoyan design bureaus and production lines viable. Therefore, if the LTA is developed successfully into an operational aircraft, then I’m sure that the VKS will purchase it on a limited scale. However, I suspect that they would prefer to increase the quantities and maturity of the Su-57 over committing to the LTA on a large scale.

What would be the hardest technology for the Russia’s to master if the aircraft is seen as a counter/alternative to F-35?

There are three key technologies which Russia will need to master before the LTA could be seen as a competitive stealth fighter in a practical combat environment:

Firstly, they would need to master compact AESA radars for use on fighter aircraft – something which is being worked on with the Su-57 but is still causing headaches. The key issue is that to be a viable stealth fighter, an aircraft must not only be difficult to detect on radar, but must also be able to detect and engage enemy aircraft without revealing itself through the energy emitted by its radar. This capability is referred to as low-probability of intercept/low-probability of detection (LPI/LPD), and it is a vital factor in the survivability and lethality of the F-22 and F-35 which is often missed by non-specialist commentators.

In very broad-brush terms, LPI/LPD radars work by exploiting the fact that AESA radars employ hundreds of individual beams rather than one or several large and more powerful ones in a mechanically scanned or PESA type radar. Use of specific frequency, wavelength and pulse repetition techniques for these many individual beams can enable AESA radars to avoid producing an easily identifiable signature within the electronic ‘noise’ of the modern air environment. However, the programming, threat EW intelligence granularity and signal processing capabilities required are highly complex and difficult to master. Furthermore, the goalposts are constantly moving as passive electronic warfare (think detection, classification and tracking of hostile signals) capabilities improve with technology. In other words, what was LPI/LPD against Russian or Chinese systems in the 2000s is almost certainly not LPI/LPD against (say) a USAF F-35A in 2025. Without a genuinely LPI/LPD AESA radar, an operational LTA would expose its position against modern opponents every time it used its primary sensor – rendering its low-observable shaping features far less useful.

The second key technology is achieving the necessary level of industrial quality control to produce viable low-observable aircraft in quantity. While bespoke hand finishing can potentially produce relatively low-observable results for prototypes, traditionally Russian fighter manufacturing has not been conducted to the extremely fine tolerances and quality control levels required to mass produce stealth fighters. This also carries over to the maintenance side of things – can the VKS (or potential export customers for that matter) afford to change their maintenance and operating procedures to a sufficient degree to maintain stealth properties in service for any length of time? For air forces used to operating previous generations of Mikoyan or Sukhoi products (with their famously high tolerance for rough conditions), it would be a culture and budgetary shock to say the least.