Category: Uncategorized

Fighter pilot shares Top Ten Myths about 1-v-1 Air Combat

10 things you shouldn’t believe about air combat

A lot of bollocks is talked about air-to-air combat, so in an effort to dispel some popular myths we approached former Air Warfare Instructor Paul Tremelling to separate the wank from the chaff. Paul is a former Sea Harrier, Super Hornet and Harrier pilot and author of this book. Over to Paul.

I’ll be honest with you. I may not have read the question which is a cardinal sin. Air combat could well mean just about anything to just about anyone. When asked for my thoughts my mind immediately went to 1 v 1. Usually assumed to only occur in the visual arena; sometimes termed Air Combat Manoeuvring, sometimes termed Basic Fighter Manoeuvres (following the usual trend for pointless rebranding), once upon a time called a ‘Dog Fight’ because ‘Cat Fight’ was already taken. That’s what came into the mind’s eye. Probably because (with the notable exception of watching a Leopard tank drive over a house one day) manoeuvring close in is probably responsible for the most compelling and exciting things my eyes have ever been asked to take in. It’s also responsible for significant periods of my eyes not working…

The idea of 1 v 1 combat is an amalgam of various threads. It makes sense that in a field where there could be a winner and a loser that there are grounds for competition. It makes sense that if one is interested in a certain technology or a given profession, then you might want to know what or who is the best at it. It makes sense from a historical stand point that one could get a relatively accurate idea about warfighting prowess in a much simplified event that closely resembled a sport. This is how we got jousting and in a historic echo this is probably why we refer to Air Combat Manoeuvring as ‘the sport of kings’; despite the very low propensity of the royals to actually give it a crack. All this combines to make 1 v 1 air combat a ripe breeding ground for all kinds of myths, misconceptions and outright lies – because the picture we have in our heads is of duelling knights obeying the rules of chivalry; going about their business to prove a simple point; probably in peacetime on largely similar mounts, on a flat field, in nice weather, both armed with the same long pole. This is a petri dish for nonsense because all sorts of things happen when lives aren’t at stake and when we try to make some incredibly complex terrain fit our ineptly simple map. 1 v 1 combat is actually about killing the opposition, who happens to be in an aeroplane. It’s about lethality, survivability, g, power, lift, speed, sensors and countermeasures. Air combat should really be viewed as jousting but where a knight is on the ground breathing his last having been shot by an archer (pun possibly intended) he knew nothing about…

A few myths for you to consider.

10. It’s all about the jet ‘God doesn’t play Top Trumps’

This is of course nonsense. We know that it’s nonsense. We even prove to ourselves that it’s nonsense by using phrases such as ‘if flown by equally talented pilots’ when comparing aircraft to show that we understand human ability has to come into the equation at some point. So how do we get ourselves into this irreconcilable piece of the Venn diagram? It’s because we have favourites. Usually based on some bias or ignorance. Which is fine – we probably mean that it’s mainly about the jet. We can probably agree that the aircraft as a weapon system is critical, but the weapon system is the aeroplane, the cueing system, weapons, the sensors, the countermeasures, other stores and the fuel load. All of which can vary dramatically from mark to mark, country to country, unit to unit and day to day.

9. These jets can always take a pounding ‘Fragile jetsculinity’

Think about an aircraft’s construction. How much of it is unnecessary? Probably very little. Unnecessary stuff costs money and adds weight. I take the point that people build in redundancy into warplanes such that they can take damage. Some warplanes can take one hell of a beating. The A-10 springs to mind. The Super Hornet had so many redundant systems that learning them was a pain. But what do you actually want a weapon fragment or 30mm (or so!) piece of metal to do? Hit something vital. How many flight paths are there through a warplane that a 30mm hole can take without hitting something? Not many. How many jets can take a missile hit in the cockpit area and survive with an intact pilot? Not many. Think about it from a weapon designer’s standpoint. He/ she wouldn’t really be earning their pay if it couldn’t crack the one job it had. Obviously things change. In World War 2 aircraft being full of a whole heap of nothing could, and did, take hundreds of rounds on occasion. The point is simple. One shell can be enough. Particularly in modern aircraft. I lost a friend to an accident that to the best of my knowledge was caused by ingestion of a single pebble – a 30mm shell is going to do more damage than that. Even if a single shot isn’t fatal – it could lead to one that is. The obvious corollary to this is that pretty much no weapons deliver a perfect kill per shot. Some fail on the rail, some in flight…and that’s before we get into weapons launched a little outside max range, a little inside minimum range or with a little too much alpha or crossing rate…those ones may not won’t work at all!

Buy The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here, and support Volume 2 here.

8. Rear hemisphere guns ‘Mauser bowser’

The gun is dead handy. It is a very effective weapon so long as you can use onboard sensors, aiming symbology, skill and luck to get your bullets into the same bit of sky as an enemy. There is a myth, or at least a very clear but erroneous picture in our minds of guns kills being scored from the rear hemisphere. Of course they are and of course that is common in training. Why? Because training rules prevent you from executing a head sector shot for reasons of collision risk and because ‘slashing’ guns kills are hard to validate on tape. A kill is a kill.

Every head sector pass is a guns kill begging to be taken. Invariably in training we will brief something along the lines of ‘Take pre-merge shots but only post merge shots to count’. This is due to the need to get into the training but in so doing we are making things significantly artificial as a good game’s a fast game and if someone’s trying to kill you then removing them sharpish is a great idea. Removing them before the fight’s even got going is a brilliant idea. I’d dearly like to engage in Basic Fighter Manoeuvres but not quite as much as I’d like to gun you in the face. The same is true of the slashing or waiting guns shot.

This involves thinking or suspecting that the enemy is going to fly through your HUD and firing with the correct amount of anticipation such that they and your deadly shot string arrive at the same time. As above…it may only take one.

7. Medium range weapons ‘Bring a cricket bat to a boxing match’

1 v 1 combat can obviously be practiced at any range you want – it just gets a little more fruity as the range decreases. This means fights can be made to fall into two buckets – beyond and within visual range. Our vision of 1 v 1 tends to be within visual range. This division is straight forward but has a number of draw backs as rules and exceptions appear neatly stacked. For example: If I know exactly where an enemy aircraft is because I can see them with my own eyes but we have yet to manoeuvre aggressively in relation to each other – has anything changed spectacularly from a second ago when I knew exactly where he was because my radar was kind enough to tell me? No. Obvs. Just because I am manoeuvring visually with an opponent does that mean that my medium range weaponry is useless? No, of course not. Some medium range weapons are truly fearsome in the visual arena and actually (think about it) have more energy than their shorter range cousins so may turn out to be the weapon of choice. It is more than possible that your medium to long range weapon is useless in a short range fight because no-one told the designer that you’d like it to work there…or the designer took the presence of the short range weapon as an excuse to over look that part of the envelope. It’s worth checking. Long and the short of it (see what I did there) it’s worth checking because your medium range weapon might well be the weapon of choice.

6. Flares work ‘Who flares wins?’

Yes of course they do. Sometimes. Do they work all of the time? No, they are clever but so are seeker heads. RF countermeasures work as well. Sometimes. They may even accidentally cause a weapon to detect a target that isn’t there and prematurely detonate. But that’s a bit of an outlier. I’m sure that most readers of this would understand that Infra Red Countermeasures don’t work at all against guns and RF guided weapons. I speak as someone who deployed IR Counter Measures against a Surface-to-Air threat that I knew was a visually aimed gun…but doing nothing felt weird. Doing something, as it turned out, felt stupid. I never really got it straight in my own mind whether or not to use counter measures pre merge – on the grounds that in my small and camouflaged aircraft, not moving relative to the enemy – I would also be unleashing dazzlingly bright magnesium. As a wise USAF head said to me one day ‘Better to be seen than be dead’. That’s true, but it’s also true that if you’re not seen they may find it harder to kill you. The counter-counter argument is that weapons are so damn fast these days that holding onto your flares until you see a launch may produce sub-optimal results. Countermeasures may work. It’s not guaranteed and one thing we can all agree on is that they will definitely run out! Shall we just leave it at that?

5. Opinions ‘Zero G contract killers’

I wanted to put this first, but thought better of it as you may give up at this point and at least you’ve read half the article. Your opinion doesn’t matter. Neither does mine so don’t get upset. What matters is the science, the context and the pilot’s ability. Too many people feel the need, or exercise the right, to talk about 1 v 1 combat without knowing what excess power is, what instantaneous or sustained turning rates are, what the actually weapon engagement zone of a specific weapon is or what sensors the platform can use to throw what shots. We’re back in that silly part of air-to-air top trumps and assignment of fighter capability based purely on what somebody said at an airshow. My brother went to a wedding once. Just about as relevant to the conversation as most opinions. Opinions need to be based upon facts. Facts to which one has actually applied conscious thought and refined with experience. Then you get an opinion. And it may still be bow-lacks.

4. It’s academic ‘If LERX could kill’

It won’t be. I was speaking to a wonderful senior officer from the USAF the other day and he co-located the nail and the hammer’s head very well. We agreed that despite the various air fleets of the free world spending years airborne and billions of pounds of aviation fuel in training – when the fight comes, it’s not going to look like an academic set up. We’re not going to charge at each other from doctrinal ranges. 1 v 1 is highly, vanishingly, unlikely to occur from being in parallel fuselages, at an agreed height and speed, confirming that both aircraft are ‘Tally’ before executing an outward and then inbound turn. Simply never going to happen. The reason we do it is the opposite. We train and train and train because when 1 v 1 happens it will be ad hoc, no notice, unscripted, unusual and fleeting. We need to be able to cope with that and the best way to do so is to give the young warriors of the free world every single opportunity to see just about every sight picture there is – so that when we do actually get into a 1 v 1 they fight and win. Quickly. By killing their opponent. If you ever hear anyone start a sentence comparing jets with the words ‘Well in an academic set up…’ feel free to get on with your pint.

3. It’s uncomplicated ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’

By this I mean that there is a myth that one can separate 1 v 1 combat from everything else that’s going on. Air Combat is necessarily complex in itself. It’s complicated by everything else. Even if there were no other fighters knocking around, or SAMs playing you’d still have to think about distance from home plate, the weather and other factors. No real point winning the fight and crashing on the way home for lack of fuel. Actually that would be a really good way of getting a Martin-Baker tie and ensuring that you were wined and dined by the weapon manufacturer for ever. This point also talks to the environmentals that no aircraft designer can really account for. From a visual perspective what is the effect on both aircraft of having cloud around. Does it seduce IR weapons? Can it mask a fighter for a critical second? How about looking down over farmland, would that suit a particular camouflage scheme. Is it better to be up in the crystal clear blue stuff or down in the industrial haze? It’ll all depend on your system, proficiency and sometimes just a preference. It may sometimes be similar, but it’ll always be different. We’ve all been in situations where we simply cannot see the other aircraft despite knowing exactly where it is – and we’ve all had the reverse, the lucky spot on a canopy glint. We’ve all tried to run for home and been shot. We’ve all shot a runner. At least one USAF kill in GW1 was down to the enemy fighter flying themselves into the ground. They all count.

2. It’s protracted ‘Time ain’t on your sidestick’

I actually fell out with a USN buddy over this. Not in a fisticuff sort of way but rather a fundamental belief sort of way. This hero, and he was a hero, believed that 1 v 1 combat was a continuum in which one flowed from one manoeuvre into the next. I was very much of the mindset that I would do anything I could to get the first shot off even if that left me poorly placed for a follow on encounter. My rationale was that there wouldn’t be one.

- You need to get the nose on ‘HOBS choice’

Nope. Not anymore. Not for a long time. Helmet mounted displays changed the game a long time ago. Early versions were fielded by the South African Air Force and then on aircraft such as the MiG-29. We all got incredibly bunched about the threat’s ability to throw an off boresight shot at us, before we remembered that we could throw one a similar angle off boresight (away from straight forward) using the radar. Then we got bunched again because working the HOTAS and watching a screen whilst manoeuvring hard isn’t quite the same ‘User Experience’ as some form of evil eye attached to your bone dome. The fact is that helmet mounted cue-ing systems changed the game and in many ways wrote a cheque that High Off Boresight (HOBS) weapons cashed. Why strive to get into the Control Zone (that bit of sky behind the enemy from which he cannot eject you kinematically) when you can simply look at the enemy and unleash a AIM-9X or other similar weapon? These weapons are extraordinary. Some can be launched over 90 degrees off boresight. Just picture what that looks like as compared to the WW1 experience of getting to height, finding the enemy and starting to circle. It looks like anything in your bit of airspace to be shot. We no longer need to stop at HMS either. How about targeting an aircraft that you can’t see other than as a track being passed to you via datalink? Can you imagine how annoying it would be to be in danger of winning a 1 v 1 only to soak up a shot that was cue-ed using a data link track from a third fighter?

But let’s join up 1 and 10 for fun. Your favourite aircraft may be amazing. But if the other person has got a slightly better electric hat…they may well come out on top. (So to speak).

Buy The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here, and support Volume 2 here.

Top 10 advanced features of the Westland Whirlwind fighter of World War II

The Westland Whirlwind: A Catalogue of Advanced Design

The Westland Whirlwind was a brilliantly designed fighter aircraft of World War II. Matt Bearman from The Whirlwind Project talks us through 10 remarkable design innovations of the beautiful and unlucky Whirlwind.

1 . The Tail Acorn

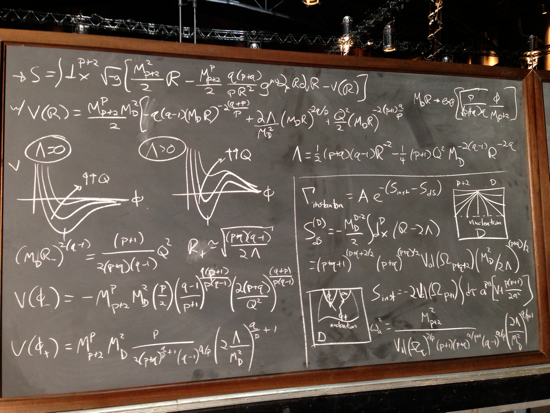

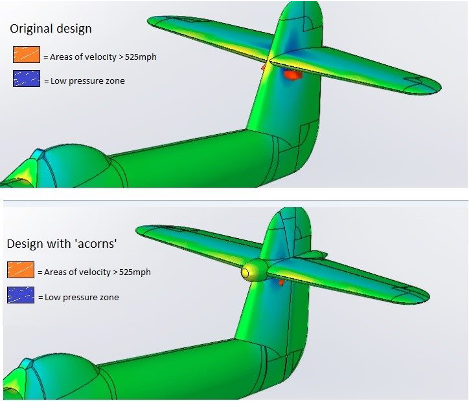

The coke-bottle shape became famous in postwar aviation as a way to avoid wave drag when going transonic – but many years before Westland had used the same shape to smooth out the pressure gradients that make for shocks around the Whirlwind’s T-tail. At the time the flutter that made the Whirlwind vibrate in a dive was understood to be the result of ‘interference drag – and whatever was really causing it, the solution was an acorn and a fairing.

The shape on the prototype’s leading edge grew from a pimple to a bulbous acorn, each iteration proving more effective than the last. The manufacturing drawing for the successful version was sent to the US military at the same time as Whirlwind P6994 was shipped to Wright Field AFB for trials.

This became the only detailed manufacturing drawing – as opposed to General Arrangement drawing – to survive, by ending up in the US National Archive in Maryland. Accompanying it is a letter from the Whirlwind’s designer-in-chief W.E.W. Petter, discussing pressure gradients and suggesting solutions to the high-speed aerodynamic problems of the P-38.

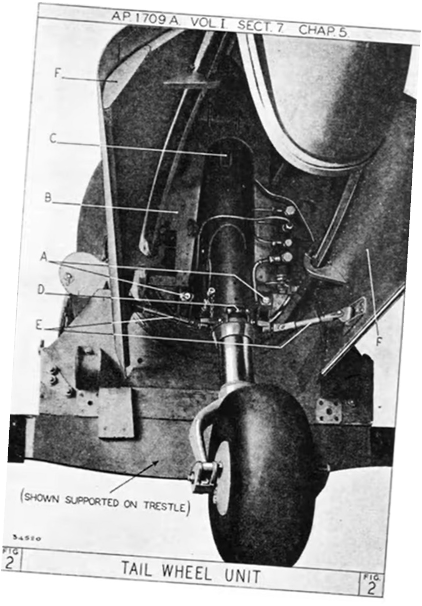

2. Retractable Tailwheel

Often overlooked, a fully retracting tailwheel with doors was not something you would normally find on a fighter in the thirties. Being new technology, it wasn’t perfect. Until modifications made it harder to break, high landing speeds and grass fighter strips meant complete failures of the unit were common – expected even. Never fatal and usually causing no extra damage, this was just an annoyance.

The mechanism was complicated – overly so, as were so many moving parts on Petter’s ‘baby’. The landing light has a complicated retracting mechanism involving hydraulics and joints on multiple axes.

Nothing was kept simple if it could be made complex – and hard to maintain for ground crews, who loved the Whirlwind far less than its pilots did.

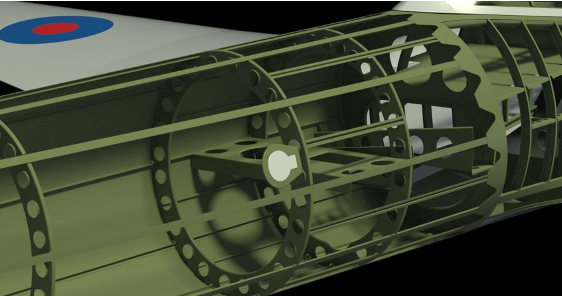

3 – Monocoque Fuselage

Truly groundbreaking was the rear fuselage. Not so much in its use of an exotic magnesium alloy instead of the more usual aluminium, but in the fact that it was a pure monocoque.

Belt and braces had been the way until then – while the principle of an aircraft’s skin contributing to its strength was well established, few designers had sufficient faith in the theory to let a tube of thin metal hold it all together without a lot of internal frames, stringers and bracing.

The Spitfire, for example, was a semi-monocoque. While the skin was ‘stressed’ – i.e. it took some of the load – it was rivetted to structural members that were intended to keep things rigid.

The Whirlwind’s skeleton on the other hand was just a series of formers with a couple of bulkheads separating modular, hollow sections. While the cockpit section had some heavier (though sometimes strangely unconnected) members, the rear fuselage really was just a lightweight, empty tube. This was fortunate as it offered smaller groundcrew the opportunity to crawl down inside to fix the frequently broken tailwheel.

4. Fowler Flaps

This was very new in the 1930’s -a flap that didn’t just hinge, it slid backwards and down. Fairly common now but revolutionary at the time, the device gave more chord and more lift – you could use it for take-off in the partially open position, as well as for landing when fully down and ‘draggy’. One odd thing about the Whirlwind’s Fowler flap is that it was just one flap, running across the entire centre-section and incorporating both the curvature of the lower fuselage and the rear of both nacelles into the moving part.

Not only did this introduce an extraordinarily complex geometry to the system of rollers, actuators, jacks and guides, the engineering challenge was compounded by linkage of this system to the cooling gills on the trailing edge.

Using cams, the cooling shutters would be held fully open at half flap for take-off and climb and almost shut, with just a small aperture for exhaust, when the flaps were either fully deployed (as in landing configuration) or fully closed (in the cruise). This was a completely automatic system which made sense in normal operation. There may even have been a slight ‘Meredith Effect’ to the shut condition, further reducing drag. However, pilots weren’t always happy with only indirect control of engine cooling.

5. Slab Sides

Whatever his engineering design quirks, Petter really did seem to know his aerodynamic theory. He may have been informed by aerodynamicist John Carver Meadows Frost, recorded by obituary as the designer of the Whirlwind’s fuselage. Frost went on to design the world’s only viable flying saucer – the Avro Canada Avrocar.

A wing has to decrease in thickness towards the trailing edge if it is to work as a wing. This makes a deeply awkward ‘hollow’ when the resulting shape meets a rounded-section fuselage low down. Worse than the dodgy aesthetics, it produces what was then called ‘interference drag’ – by the bucketload.

Designers were trying endless variations of fillet shapes to fill the gap, like the Spitfire’s huge fillet with inflections and double curves that needed a craftsman, an English wheel and several days to make. In 1937 Petter – or perhaps Frost – had a lightbulb moment. This was really all about pressure gradients – just make the fuselage side locally flat, leave the gradients to the wing, and the problem goes away. Frost later used his insight into pressure changes to make the Avrocar fly.

The unorthodoxy of this shape has meant that artists and model kit designers have given the Whirlwind a small fillet ever since. It never had one – it’s just an illusion created by the peculiar transition from flat sides to a round frame aft of the trailing edge.

6. Bubble Canopy

Fighter pilots have always been as concerned about what is behind as in front. Although enclosed cockpits gave the opportunity for at least some comfort, a common complaint was not being able to see an attack shaping up from the rear.

Drawings for Westland Aircraft Co’s proposed P-9 from early 1937 show a perfectly smooth, teardrop-shaped and fully transparent canopy. This was extraordinarily ambitious – the technique and tooling to manufacture of such a large acrylic bubble didn’t exist. It was as though Petter was assuming it would be invented before he had to build a prototype.

Whatever inside information Petter possessed, as it was also in 1937 that Mouldrite, a division of ICI, began producing beads of their new ‘Perspex’ material that could be placed in a large mould to produce a complete rounded canopy.

7. Slats

Sitting on the leading edge of each outer wing, these spring-loaded slats were meant to ‘pop out’ at low speed and delay the stall. It was a piece of advanced aerodynamics that was generally sound but the automated deployment presented problems. Being independent, if one wing was closer to the stall than the other – in a tight turn for example – only one slat would deploy.

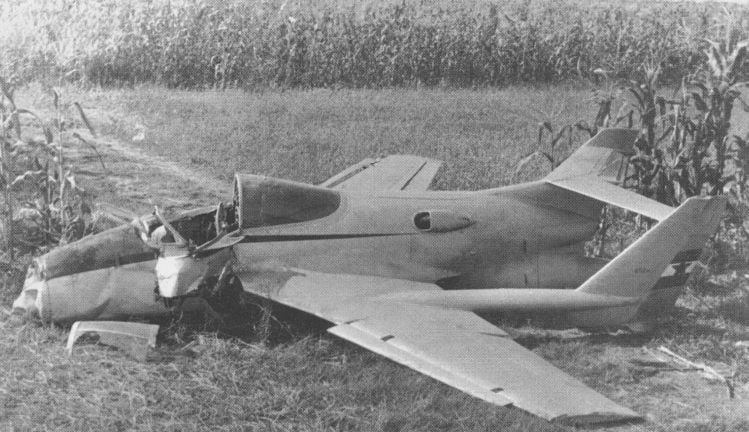

The asymmetry was often too much for the aerodynamic balance of the fighter and two Whirlwinds came down as a result before the slats were simply wired shut in 1942.

8. Leading edge intakes

This was a real shot in the dark by Petter. There had been no research anywhere in the world into what effect taking a large chunk of the leading edge out of a wing would have on lift and drag at the time of the design. It was a suck-it and see design that more or less worked. The duct itself, containing radiators and oil coolers, was designed – sculpted even – according to the work of Fred Meredith of the Royal Aircraft Establishment, whose work was later ‘borrowed’ by the North American Aviation team to produce the P-51’s drag-reducing belly scoop.

It is a tribute to Petter’s instinct that the wing performed as well with the large aperture in the leading edge as without, whilst having no external protuberances for cooling did make the Whirlwind slipperier than most. Retracted flaps narrowing the exit aperture and capturing the ‘Meredith Effect’ helped.

However, the complete lack of data on how to avoid flow breakdown inside the duct meant that very often not all the air that should have got to the radiators did, and overheating did happen. How much of that was due to the shockwaves coming off the propeller blades (spoiler alert) and how much was down to turbulence generated by the lips and walls of the duct will probably never be known – but it added to the myth of ‘unreliable’ engines.

9. Cannon

Nothing so subtle about these. While many of us now admire the Whirlwind as a flying machine, the four prominent 20mm cannon are impossible to ignore – The Whirlwind was after all a weapon of war and it functioned as a piece of flying artillery. Developed from the Oerlikon FF S, the 20mm Hispanos were aimed by simply looking down the nose. The concentrated fire needed no ‘harmonisation’ – they all pointed the same way and delivered rounds within inches of each other regardless.

Though the Whirlwind was mooted as a ‘Bomber Destroyer’ – essentially an interceptor – it was rarely used for this. Even during the Battle of Britain, it was recognised that the Whirlwind was better suited to other tasks. Should German armour have attempted to cross the channel, the barges would have had little chance on encountering a Whirlwind. Any vehicles that made it across would have been intensely vulnerable to the cannon. All the Whirlwinds delivered by the Autumn of 1940 were kept back in Scotland by Dowding for this possible use.

From 1941 until 1943 the relatively few Whirlwinds in service wreaked havoc on ground targets in occupied France using these weapons, as well as the 500lb bombs they were later modified to carry.

10 . The Culprit – DH Constant Speed Propeller

The big one. It was discovered in 2018, by this author, that there was in fact nothing wrong with the Rolls Royce Peregrine engine, the one famously blamed for the Whirlwind’s cancellation. What looked like an inexplicable fall-off in engine power with altitude was in fact an entirely explicable fall-off in the propeller blades’ ability to turn power into thrust. To explain requires a series of concepts of varying degrees of difficulty to be ‘lined up’ and born in mind simultaneously.

The first is that a propeller blade is an aerofoil, working perpendicular to line of flight. All aerofoils accelerate air over their surfaces. Propeller blades are moving considerably faster than the aeroplane they are attached to, their velocity a combination of rotation and the aircraft’s forward movement. With all this it is inevitable that locally over the blade’s foil some air will become supersonic, especially further out where geometry means the blade section is moving faster for any given rpm.

That was the easy bit.

The fatter an aerofoil, the greater the local acceleration. Modern thin propeller blades won’t go ‘locally supersonic’ right up to the point where they are actually hitting the speed of sound – and even then the resultant shock, and drag, will be less. Fat aerofoils hit big problems much earlier. The Whirlwind’s propeller blades would start to create shockwaves at a combined blade velocity of 0.7 Mach.

Now bear in mind that the speed of sound decreases with altitude. So at combined speed of, say, 575 mph a fat bade section would produce no draggy shockwaves at 1,000 feet and yet be an aerodynamic mess at 30,000ft.

It all comes together when one considers the final innovation of the Whirlwind, the De Haviland Constant Speed Propeller. The idea is simple enough – all reciprocating engines have speeds at which they are most powerful or most efficient. Cars use gearboxes to keep close to a desired rpm whatever the speed. The constant speed system – of which the Whirlwind was a pioneer – works a little like an automatic gearbox. When it senses deceleration, it lowers the angle of attack of the propeller blade aerofoils. Drag on rotation decreases, and rpm comes back up. Too fast, and the blades go ‘coarse’ again, to slow it down.

As the Whirlwind climbed, it started to experience shockwaves on the blades. The higher it went, the draggier things got for the propeller. The constant speed unit, oblivious to the real cause of the drag, simply fined the blades in response, keeping up the revs. It wouldn’t stop until it had passed through a negative incidence, producing no thrust whatsoever. The Whirlwind appeared to lose power at height and as almost no-one had knowledge of transonic aerodynamics, nearly everyone blamed the engines, including Petter himself. Famously, this got the program cancelled.

You can support the project here. Buy The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here, and support Volume 2 here.

Military aircraft identification quiz (VERY HARD) from Hush-Kit

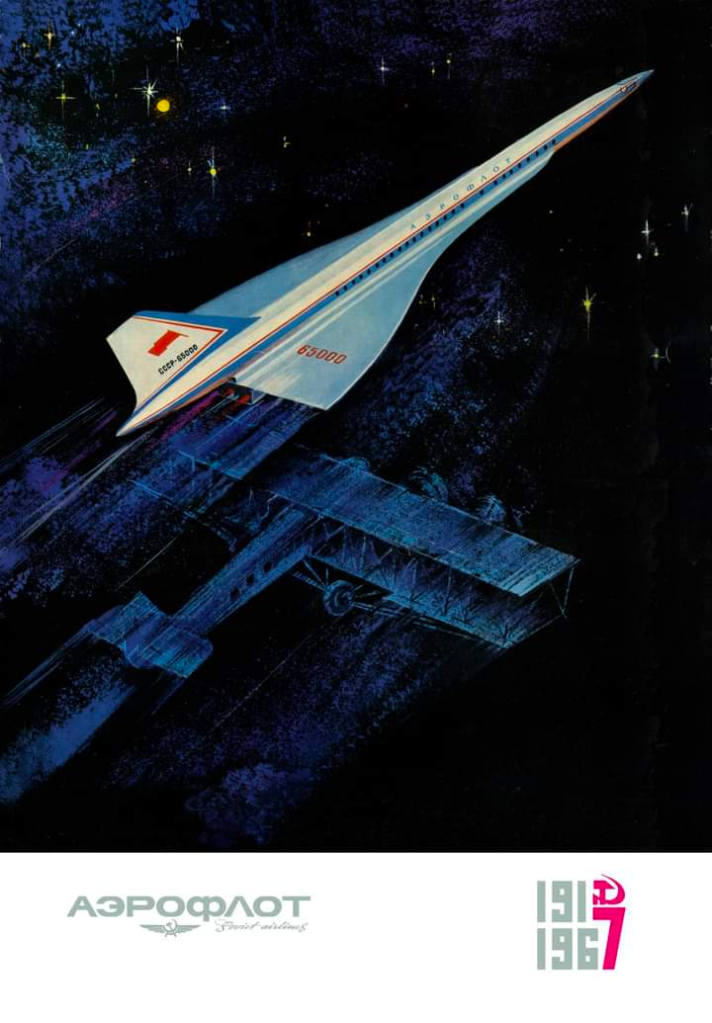

Epically Soviet Images from Aeroflot of Classic Aircraft

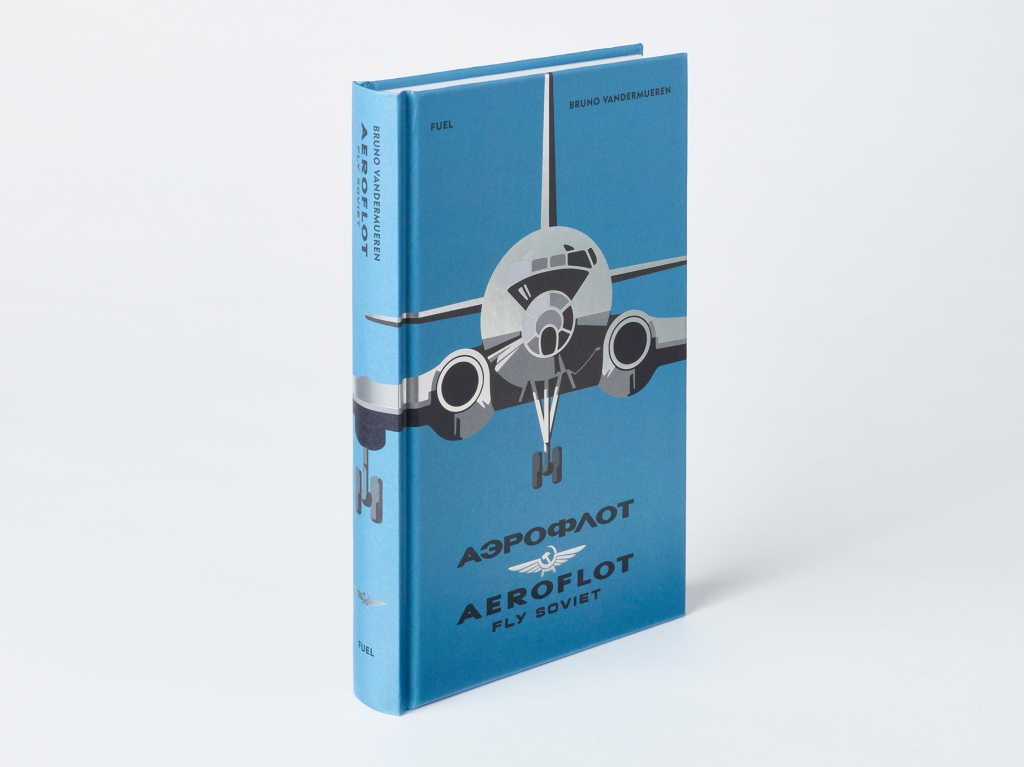

Soviet airline memorabilia to break the ice

There’s a particular exotic glamour to artefacts from the Soviet-era Aeroflot airline. Perhaps this why one of my favourite aviation books of recent times was the exquisite Fuel book of the Aeroflot ephemera of Bruno Vandermueren. With this in mind I tracked down Bruno to choose his 10 favourite pieces from his collection.

10. Timetable winter 1937-38

On the cover, a PS-89 equipped with skis flying in a snow storm over an industrialised town. It was at the height of the Stalin’s Great Purge.

Only 8 of these aircraft were build and a timetable from this period is almost as rare as the aircraft itself. This particular copy I picked up in Kiev a few years ago thanks to one of my local contacts.

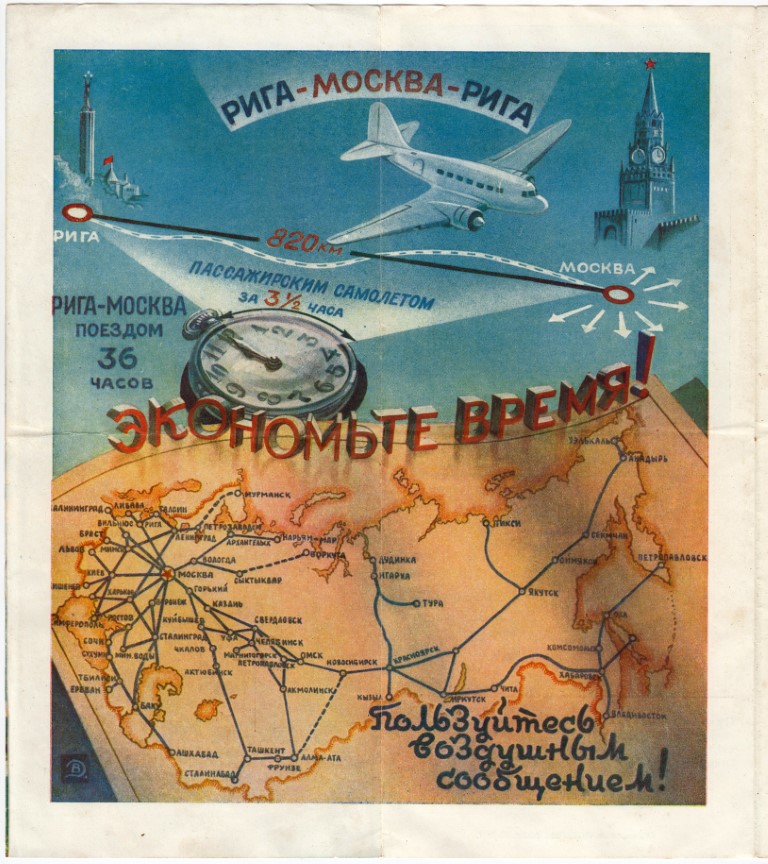

9. ‘Riga-Moscow-Riga’

Save Time! Use Air Transport! Riga – Moscow, 820km. By train 36 hours. By passenger airplane 3,5 hours’. The map shows the entire USSR with the Aeroflot trunk routes.

The brochure is undated but seems to be from the early 1950s. In those days, publicity used the slogan ‘Use Air Transport’ without mentioning ‘Aeroflot’. It was a time when most long distance travel was done by train. Colorful promotional brochures started to appear to entice the population to fly by airplane instead. This plane – train comparison of travel times and ticket prices was common until the early 1970s.

8. Brochure describing the Moscow – Khabarovsk route

Long distance routes in the early 1950’s were quite an undertaking. The Ilyushin Il-12 made 8 intermediate stops: Kazan – Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) – Omsk – Novosibirsk – Krasnoyarsk – Irkutsk – Chita and Tygda. Total flight time was 22 hours while the total journey took some 33 up to 42 hours, depending on the schedule. This was in case everything went as planned but during the first years in Aeroflot service, the Shvetsov Ash-82FN engines weren’t very reliable and had to be overhauled every 100-150 hours.

The brochure was designed by Sergey Sakharov, one of the leading artists in Soviet advertising creating famous posters for vodka, cigarettes and fruit juice. His work for Aeroflot included several posters and my collection includes other brochures of his hand like ‘Moscow – Tbilisi’, ‘Moscow –Tashkent’ and ‘International Air Routes of the Soviet Union’. I’m still trying to find ‘Air Routes to the Resorts of the Caucasus’, ‘Air Routes to the Resorts of Crimea’ and ‘Moscow – Tashkent’ but it’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.

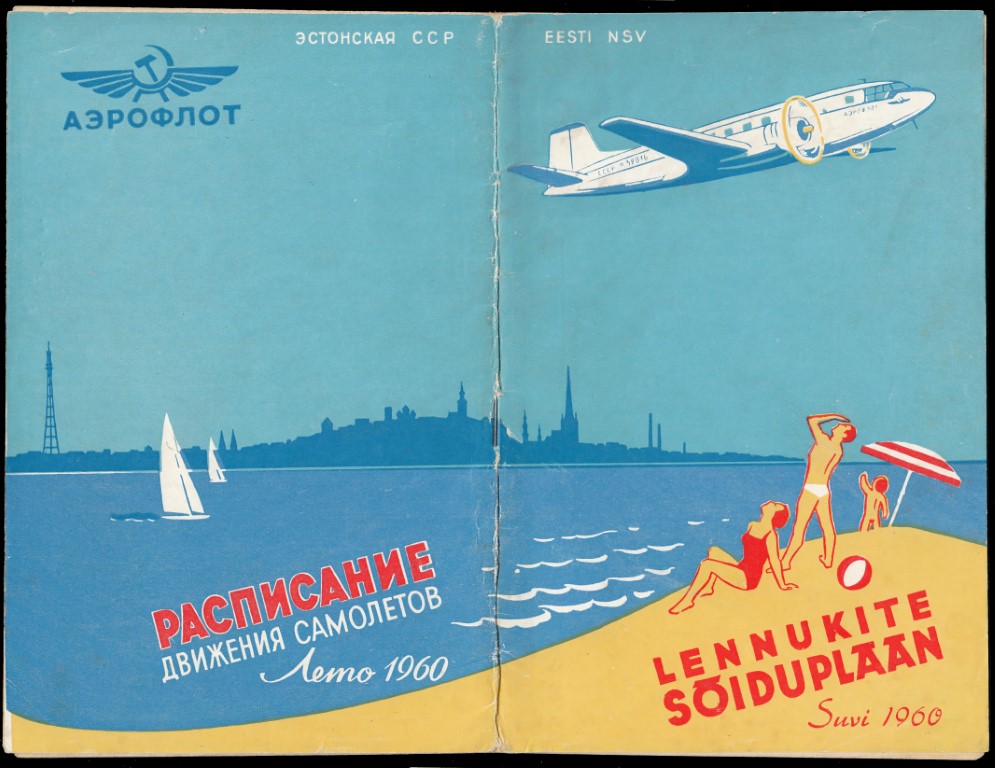

7. Timetable for summer 1960 of the Estonian Aeroflot Directorate

It depicts the Tallinn skyline as seen from the beach and an Ilyushin Il-14 is flying overhead.

Local timetables are among my favorite Aeroflot ephemera. Although most were not as colorful as this one, they always make for interesting reading. Often the schedule was simply printed in a local newspaper. In the USSR, even many small villages and settlements had an airfield, grass strip or a nearby river which could be used to land, in total some 3,500. Some of them are difficult to find on a map. This led me to draw local route networks based on these timetables. Nowadays, literally thousands of these places in the ex-USSR are not connected by air anymore.

Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 here.

6. Civil Aviation magazine 11/1962 ‘Under the Aeroflot Emblem’ by A. Kirillova

This monthly magazine never had a high circulation and, as with other ephemera, most copies were simply thrown away over time. I’m still missing several editions but this cover from November 1962 with the Tupolev Tu-104 and Aeroflot hammer and sickle logo is definitely among my favorites with still some influence of constructivism.

5. Antonov An-10A brochure published by ‘Avtoexport’ (Car export) before ‘Aviaexport’ was established in 1961.

After a crash near Kharkiv in 1972, the first Soviet turboprop airliner vanished from Aeroflot service. For this reason, the An-10 is often overlooked although it played an important role in the development of Aeroflot.

Its cargo twin sister, the An-12 has proven to be a tireless workhorse. Even today, half a century after production ended in 1973 and the grounding of the An-10 fleet, several An-12 are still flying regularly in the service of cargo operators from ex-Soviet countries. While writing this, I can hear the hum of a Cavok Airlines An-12 flying at 20,000ft over my home near Brussels and whenever I can, I visit Ostend airport to see them in action up close.

4. Tupolev Tu-144 cigarettes produced in Moscow by the Java tobacco factory for Aeroflot’s 50th anniversary in 1973. At the time, it was still common to smoke on board an airplane.

Several years after I acquired this cigarette pack, I saw a picture of a similar one depicting an Il-18. Only then I realised it must have been part of a series of cigarette packs depicting the aircraft types in the fleet. It would take another decade before I stumbled across the entire box set of 10 cigarette packs for sale on eBay by a British seller. It contains the An-24, Il-18, Il-62, Mi-8, Tu-104, Tu-124, Tu-134, Tu-144, Tu-154 and Yak-40. The fact that I never found these cigarettes in a former Soviet country was because they were, most likely, only sold in the Soviet ‘Beriozka’ shops. These shops sold luxury goods to foreign tourists in exchange for foreign currency and were not frequented by the local population.

3. Panoramic postcard from 1979 of an Aeroflot flight crew at Elista airport, North Caucasus

Among the many hundreds of Soviet airport postcards, it remains one of my favorites. It expresses the typical atmosphere of a Soviet regional airport: the crews, a Yak-40, the airport terminal with the waiting area outside and the rough concrete surface. Only the passengers, stray dogs and an old ZIL fuel bowser are missing.

2. Promotional brochure showing the Ilyushin Il-86 take-off from its birthplace Moscow-Khodynka airfield

The two almost identical buildings are the Aeroflot hotel and the administrative building with in between the Moscow City Air Terminal where passengers could check-in, drop off their luggage and choose direct transport to their airport of departure.

When I was in Moscow in 2017, the air terminal was about to be demolished. New shopping malls and other buildings were erected everywhere around but while walking in that area, one could still witness the presence, or at least the remnants of a great aviation legacy. Several aircraft design bureaus were located at the Khodynka field, not in the least the Ilyushin bureau. All Il-12, Il-14 and Il-18s had been constructed there, as well as the prototypes of the Il-62 and Il-86. It must have been quite a sight seeing them take off from the heart of the city.

- Moscow – Algiers – Conakry – Dakar by Ilyushin Il-62

To conclude this nostalgic journey through Aeroflot ephemera I’ve chosen an advertisement announcing the new weekly service Moscow – Algiers – Conakry – Dakar by Ilyushin Il-62 on the back cover of ‘Soviet Union’ illustrated magazine of February 1969.

Flight SU-065/66 departed Moscow Sheremetyevo every Thursday morning, stayed overnight in Dakar to fly the same route back to Moscow arriving on Friday just before midnight. Inflight service on international flights was always of a high standard and the Il-62 was definitely one of the most comfortable airliners of its time.

Back then, in the winter of 1968-69, Aeroflot operated regularly to 48 international destinations. By 1990 this number had risen to 119. Most of them out of Moscow but also a few out of Leningrad, Khabarovsk, Irkutsk, Kiev, Minsk, Tashkent, Yerevan and Vilnius.

The world and the aircraft have changed a lot since then but these ads continue to inspire and make one wants to travel, not only to a new destination but also back in time.

Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 1 here.

Or subscribe to our free newsletter here and get jet-noise straight into your inbox

My Top 10 Cancelled Warplanes By Tony Buttler

My Top Ten Projects, Cancelled Aircraft and Experimental Prototypes

Quite some time ago Hush-Kit’s Joe Coles kindly asked me to write a piece for the Hush-Kit site. I apologise for taking so long, but this is the result.

Joe asked for my thoughts on my Top 10 cancelled and abandoned aircraft – my clear favourites, the types that fascinate me the most, and the most obscure aircraft I can think of. To be honest that was not the easiest thing to do. I have a lot of favourites among the cancelled and rejected projects and to eliminate so many was a test in itself. But what follows is a good cross-section of those types which I have enjoyed writing about. Most were built and flown but one, the Hawker P.1083, only got as far as an incomplete prototype.

If you love cancelled aircraft, you should certainly pick up a copy of The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes, which features a wide variety of exotic military aircraft portrayed in superb new illustrations, among many other warplanes, interviews, articles and top 10s.

Over the years I have written a good deal about bombers and ground attack aircraft, but for all of my life it has been the fighter and interceptor from the mid-1930s onward, and those research types associated with this category, which have interested me the most. So, with apologies to bomber fans, almost all of the aircraft which follow were in general associated with air defence, interception and dogfighting. And I’m afraid my choice has also been governed by the appearance or ‘good looks’ of each type, because to be a favourite for me an aeroplane design needs to be able to catch one’s eye.

A outcome of this last point is that Hawker Aircraft have contributed three different types to the list. I have recently prepared a lecture for the Hawker Association covering the one-off test bed and experimental prototypes proposed and built by this firm, and while putting it together I realised that Hawker must have designed more beautiful fighter aircraft than perhaps any other fighter design team in the world – I would suggest that North American Aviation is the one that comes nearest – what do you think? I could easily have included the Hawker Tempest I and the Napier-Sabre-powered Hawker Fury prototypes here as well!

I must raise one point about making judgements on cancelled aircraft projects, a point which was first suggested by a great friend of mine. And that is there is a tendency to always look at ‘what might have been’ with dreamy eyes and without looking at the situation and the hard facts. He cited the 1950s British Supermarine Swift jet fighter, a programme which perhaps should have been killed off early on. Had the latter been the case, there are undoubtedly aviation historians and authors who would have written that it was a disastrous decision, and that the Swift would have been a superb fighter! In fact, as a pure fighter it was a failure and it was the later fighter-reconnaissance FR.Mk.5 variant which would give the Swift something of a modest Service career.

Aircraft projects and programmes can be cancelled through many reasons – cost, modern technology making them obsolete (like the jet replacing the piston engine) or that simply they were just no good. Each specific case will have more baggage ‘attached’ to it in terms of situation and background than many might realise. Don’t forget as well that the UK does not have, not by any means, the monopoly on cancelled aircraft projects.

All of the types described below date from the 1940s and 1950s, for me perhaps the most exciting time in aviation history. Do please remember that this is a personal choice. I am sure all of you reading the text that follows would pick an entirely different group of favourites, but I hope you will agree that there are some interesting and fascinating aeroplanes here. Thank you for taking a look.

Tony Buttler June 2023

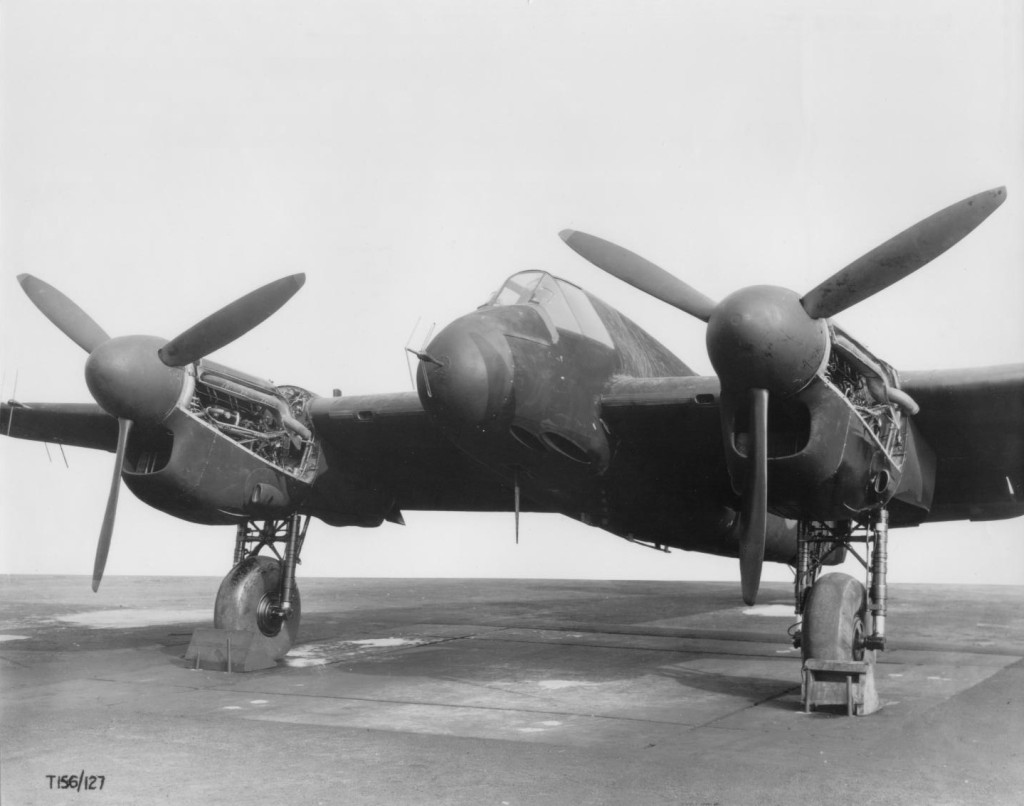

FMA IAe 30 Ñancu (Argentina) 1948

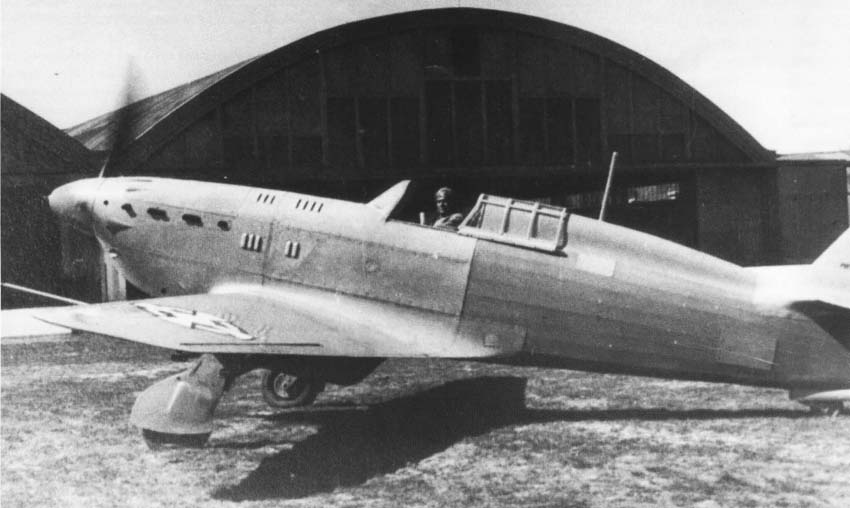

One of my all-time favourite fighter-type aeroplanes has to be the de Havilland Hornet and Sea Hornet, but these had a successful production run and good careers and so do not qualify for inclusion here. The Hornet had followed the wartime Mosquito and it is quite extraordinary I think that Argentina built two aircraft types that were not only direct equivalents to, but also looked very similar to, these British machines. Just over 100 examples of the IAe 24 Calquin attack bomber, a Mossie look-alike, were built, but only one IAe 30 Ñancu would be flown.

After WW2 many prominent designers and pilots from Germany and Italy would move on to Argentina to work for the new aircraft industry based there. After the Mosquito-like Calquin, it was perhaps no surprise that Italian Cesare Pallavecino (FMA Chief Designer from late 1946), when asked to design a high speed twin-engine escort fighter to protect the Air Force’s Avro Lancaster and Lincoln bombers, would produce something which looked much like the Hornet. In fact the Ñancu was not nearly so similar to the Hornet as the Calquin was to the Mosquito, but came close in the wing and nacelle areas and it used the same engines.

The Ñancu was one of the last piston-engined fighters built anywhere in world. Its name, pronounced ‘nyanku’, referred to an Eagle which inhabited the Patagonian plains. It was an all-metal aircraft with a triangular or ‘pear-shaped’ cross section (the Hornet had a more oval fuselage) and again, like the Hornet, Ñancu’s Rolls-Royce Merlin 134/135 engines were handed (i.e. opposite rotating). It was to have four 20mm cannon mounted in the lower nose, although the prototype never received any weapons but instead featured a transparent nosecone. The first flight took place on 17th July 1948 with the aircraft piloted by IAe chief test pilot Capt Edmundo Osvaldo Weiss.

Comments on Ñancu’s performance proved very favourable and there were few problems. In all 210 production aircraft were planned but progress was slow. However, Weiss did record over 550mph in a dive and he reached a speed of 485mph on the level. Due to ever increasing financial problems, however, the production run was never started and the Ñancu was cancelled late in April 1949. The only flying prototype was lost in a landing accident later that year, while work on a second machine was started but never completed. Ñancu was an excellent aircraft but unfortunately arrived at the same time as IAe’s Pulqui II jet fighter, and so was rather pushed out of the picture.

Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow (Canada) 1958

I guess one could call this dramatically impressive interceptor fighter the ‘Canadian TSR.2’, because the abandonment of this extraordinary machine is probably just as controversial as was the dropping of the British Aircraft Corporation TSR.2 strike aircraft in 1965. In April 1953 the Canadian Air Force issued a demanding specification which requested a sustained speed of Mach 1.5. The Avro Canada company responded with a very large delta wing design, prototypes were ordered in December 1953 and in 1954 the type was designated CF-105, but it was not officially named Arrow until early in 1957. In service it was to be powered by two home-grown Iroquois jet engines, but the first examples would have American Pratt & Whitney J75 units.

The first of five prototypes first flew on 25th March 1958. The biggest problems centred on the development of the weapon system and the ever growing cost, eventually pressure began to build on the project and its future became uncertain. The possibility of overseas customers might have helped and the CF-105 was examined by both the United States and the United Kingdom, with much interest coming from the British RAF. But no orders were forthcoming.

Gradually the Arrow became a very political aeroplane with much discussion over its cost, and also if it was really needed. The project was finally cancelled on 20th February 1959 in a move which also destroyed a substantial part of Canada’s aviation industry; Avro Canada went out of business and the CF-105 assembly line, tooling and the existing airframes and engines were ordered to be destroyed.

At cancellation five CF-105s had flown and the flight test programme overall had progressed smoothly with relatively few aerodynamic problems. A total of 70 hours airtime had been accumulated and Mach 1.95 had been reached at a height of 42,000ft. For Canada’s future air defence the Arrow was replaced by the American McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo fighter and the Boeing Bomarc surface-to-air missile, again controversial acquisitions.

Hawker P.1081 (UK)

To be honest the Hawker P.1052 and P.1081 need no introduction – these are very well known aeroplanes. They were built purely as research aircraft to investigate the benefits of swept back wings and initially two Rolls-Royce Nene-powered P.1052s were ordered as swept wing versions of the straight wing Hawker P.1040/Sea Hawk naval fighter, but retaining that type’s straight tailplane. The first, VX252, first flew on 19th November 1948 piloted by Hawker test pilot Trevor ‘Wimpy’ Wade and it proved a success.

In due course the second P.1052, VX279, was heavily modified with an all-through jet pipe and a swept tail and fin to become the P.1081. These are lovely aircraft and the P.1081 in particular has always been a favourite for me since it looked splendid. As modified, Wade took VX279 on its second maiden flight on 19th June 1950 and it was displayed at that year’s Farnborough Show in September. But, tragically, on 3rd April 1951 Wade was killed when the P.1081 was lost in a crash, the reasons for which have never been fully established. Nevertheless, the P.1081 can be considered as the final link between the Sea Hawk and what would become the gorgeous and hugely successful Hawker Hunter, another of my all-time favourites.

Hawker P.1083 (UK)

The P.1083 was an attempt to produce a Hawker Hunter capable of supersonic flight on the level, a move which basically involved fitting more highly swept wings, set at an angle of 50°, to the original fuselage. A full go-ahead was given by the Air Ministry on 12th December 1951, and in April 1952 a new Specification was issued to cover the design of the ‘Hawker Interceptor Fighter’ fitted with a reheated Rolls-Royce Avon RA.14R engine. However, in early April 1953, well into the manufacture of the prototype, the Air Staff requested that the P.1083 should now be armed with the de Havilland Blue Jay (Firestreak) air-to-air missile as its primary weapon, which then brought problems with a lack of space inside the airframe for radars and other equipment. The P.1083 had originally been developed as an improved performance Hunter and was to be armed with guns only – it was not intended to be a guided weapon carrier.

A Ministry memo dated 9th June 1953 declared that, thanks to previous flight test problems experienced with the Hunter, and coupled with the difficulty of fitting reheat to the engine and the lack of room for extra fuel and equipment inside the P.1083, the supersonic aircraft was now to be cancelled and work was to cease forthwith (at this stage it was also considered that the Hunter made a less attractive project than the rival Supermarine Swift). As a consequence Hawker’s design team spoke to Rolls-Royce about fitting the RA.14 into the standard Hunter airframe and in August the Air Ministry agreed that the firm should proceed with a non-reheat version of the aircraft with this larger engine. In due course the front and centre fuselage and the tail from the cancelled P.1083 prototype, serial WN470, were used to construct the Hawker P.1099 serial XF833, which became the prototype for the Hunter F.Mk.6 series. As such it first flew on 23rd January 1954.

Hawker P.1109 (UK)

During the mid-1950s studies had shown that, with the increased engine power of the Mk.6 Hunter, the radar/missile combination of AI.Mk.20 and Blue Jay could be fitted to the standard subsonic fighter to provide an increased capability without any loss of performance. Hawker was asked to do a study and the firm called the new version the P.1109. It would carry only two guns to reduce the nose weight and the most visible external change was the nose shape which increased the length by about 3ft. The standard F.Mk.6 Avon engine was retained.

In May 1956 the Hunter/Blue Jay programme was officially cancelled, but the Ministry of Supply encouraged Hawker to continue with it on a private basis. It was agreed that the firm would equip and fly one aircraft fitted with Blue Jay missiles within a three aircraft programme. Hawker would clear the in-flight handling before de Havilland Propellers (the weapon manufacturer) would take over the aircraft for firing trials. Serials WW594, WW598 and XF378 were converted to this configuration in 1956, but only XF378 was fully equipped with the complete Firestreak plumbing and pylons to take the missiles. P.1109A was the designation given to the aerodynamic test aircraft without any missiles, P.1109B was the full conversion.

The Green Willow AI.Mk.20 fire control radar was intended for single-seat fighters but it was manufactured only in a short run; possibly no more than five examples. It was developed as a back up for the AI.Mk.23 then being designed for the English Electric P.1 (Lightning) and it was never used operationally.

XF378 first flew with two Blue Jays and an AI.20 radar installation on 12th September 1956. During trials the highest achieved airspeed by a clean P.1109 was 620 knots and the highest altitude 55,000ft; the maximum recorded Mach number was 1.16 in a steep dive from 51,000ft. Overall, the general handling did not appear to have been appreciably affected by the modified nose. A dive from 48,000ft down to 25,000ft enabled the ‘armed’ aircraft to reach Mach 1.09, and the full throttle level speed at low altitude was 605 knots at 2,000ft. The general handling of the P.1109B XF378 with two Blue Jays was very satisfactory.

XF378 attended the Farnborough Show in September 1957, by which time the missile trials programme was pretty well done. However, the three airframes did find other roles. The two P.1109As moved on to RAF West Raynham for special trials and WW598 also spent time with the Royal Radar Establishment at Defford and with RAE Bedford, before going to RAE Farnborough. XF378 was written off in 1959 after a fuselage fire.

At the Air Fighting Development Squadron at West Raynham it was found that a standard Mk.6 Hunter flying at about 50,000ft experienced great difficulty in keeping up with the P.1109 at that height; the latter still had plenty in hand and in due course could leave the normal aircraft behind pretty quickly.

The Hunter P.1109 programme was an interesting and worthwhile exercise and was regarded by many as the best looking of all Hunters. Certainly by me!!

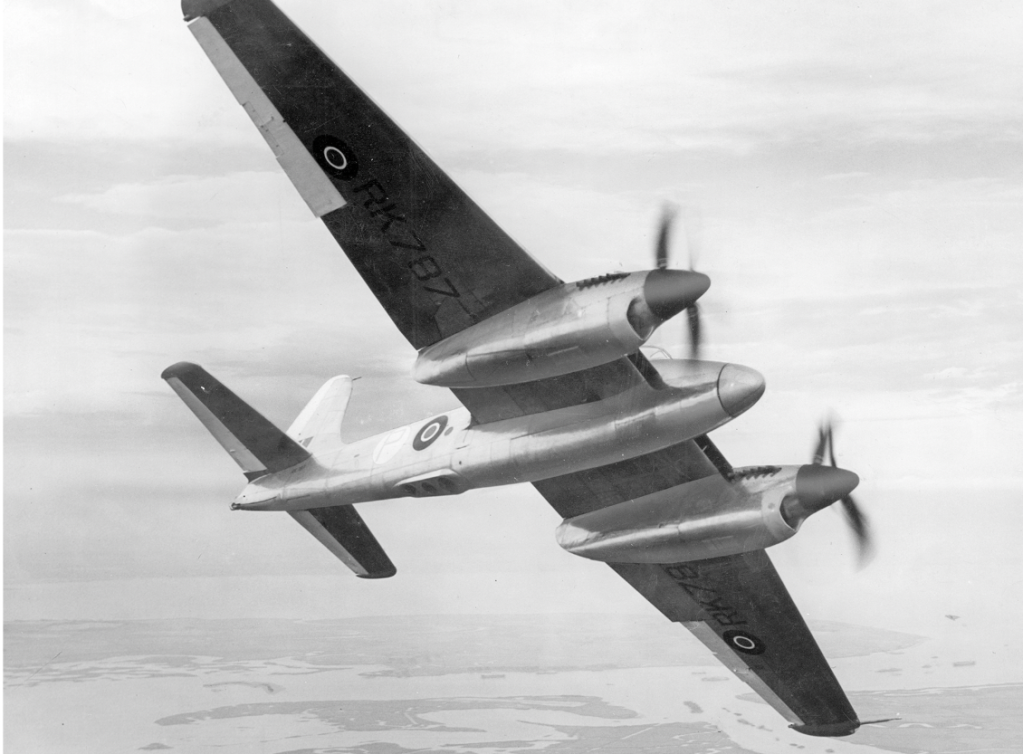

Short Sturgeon (UK)

The version of this aircraft which I am referring to here is the original torpedo bomber in prototype form, just two airframes in total, and not the target tug versions that followed. Apart from again looking attractive in my eyes (especially for a bomber or attack type), the Sturgeon is also of great interest in that it had contra-rotating propellers on each engine, which removed the problem of torque and swing for twin-engine aircraft taking off from and landing on aircraft carriers. As such it makes an interesting comparison to the de Havilland Mosquito and Hornet. The former had single propellers rotating in the same direction, which meant that swing to the right had to be countered during the take-off run. The Hornet had solved this problem by having ‘handed’ engines – that is the single propellers on each unit rotated in opposite directions. The Sturgeon’s contra-props provided another solution to the problem of swing.

An Instruction To Proceed was given to Shorts in October 1943 for a twin-Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered project which was eventually called the S.A.1 Sturgeon. Three S.Mk.I prototypes, RK787, RK791 and RK794 were ordered and RK787 made its maiden flight on 7th June 1946. The Sturgeon was essentially designed for operations in the Pacific as part of preparations for the final drive against Japan, but after that conflict had ended the Navy was left with a new bomber and nowhere to use it. As a result the bomber Sturgeon did not enter production, but before the end of the war it was turned into a humble target-tug as the TT.Mk.2 variant. The third S.A.1 prototype, RK794, was modified to act as the prototype. Reserialled VR363, it first flew on 18th May 1948 and 24 production aeroplanes followed.

Supermarine Spiteful and Seafang (UK)

One of the fastest piston fighters ever! And one reason why these types interest me is because the later Rolls-Royce Griffon-powered versions of the Spitfire and Seafire are my favourites from that tremendous family of fighters and the Spiteful and Seafang were concurrent types which, with their tapered laminar flow wings, offered a direct comparison to the Spit’s elliptical wing. In the end the elliptical type would still prove to be as good as the Spiteful wing, which in itself shows just how good designer R.J. Mitchell’s original Spitfire wing had been back in the mid-1930s when it was first designed.

In order to improve the Spitfire’s rolling characteristics Supermarine had been asked by the Ministry in 1942 to produce a new wing. At the same time it was also considered advantageous to have a laminar flow section on this wing and the result was known as the laminar flow wing or, on occasion, the ‘thin wing’. Theoretically the laminar flow wing was designed to move the boundary layer transition point further aft on the wing surface so that the point at which the airflow over the wing became turbulent was delayed, and drag was thus reduced. The main benefits were expected to be an increased performance from the laminar flow, the avoidance of compressibility effects and improved rolling manoeuvrability from the smaller span. Compressibility was a growing problem caused by flying at speeds ever nearer to the speed of sound, and ever more powerful engines meant that the aerodynamics needed to cater for this.

Three aircraft were ordered and Supermarine called the new aircraft its Type 371. There were discussions for a new name and by March 1944 production 371s were being called ‘Valiant’ by the Ministry, but the new fighter was eventually named Spiteful. The first aircraft to fly with the new wing, Spitfire Mk.XIV NN660 converted as a hybrid Spiteful prototype, made its first flight on 30th June 1944. The first true prototype, NN664, completed to full production standards, flew on 8th January 1945, but subsequent flight trials indicated that the hoped for advances over the Spitfire had not been achieved.

Tests on the modified Spitfire allowed a direct performance comparison to be made and the laminar wing did produce an increase in speed over the standard Spitfire wing, but it was disappointingly below the figure expected. Also, any slight degree of surface roughness, even from an impacted insect, could markedly reduce the speed. In addition the new version displayed poor stalling characteristics and more adverse compressibility characteristics than had the old elliptical wing.

Due to cutbacks brought about by the end of the war only 17 Spitefuls were completed from a planned run of 650 but several were used to improve the laminar wing’s aerodynamics, or to test alternative powerplants. One, RB518, recorded a speed of 494mph at 27,500ft, the highest speed ever achieved by a British piston-powered aeroplane.

In October 1943 Supermarine began to consider fitting the laminar wing to the Seafire and proposed this as the private venture Type 382. Initially this was not taken up but interest from the Admiralty began to grow and eventually a naval version of the Spiteful, called the Seafang, was ordered. Spiteful RB520 was fitted with a hook and flew in early 1945 as an interim Seafang prototype, but the first true prototype was VB895. A total of 150 Seafangs were planned but just eight were completed.

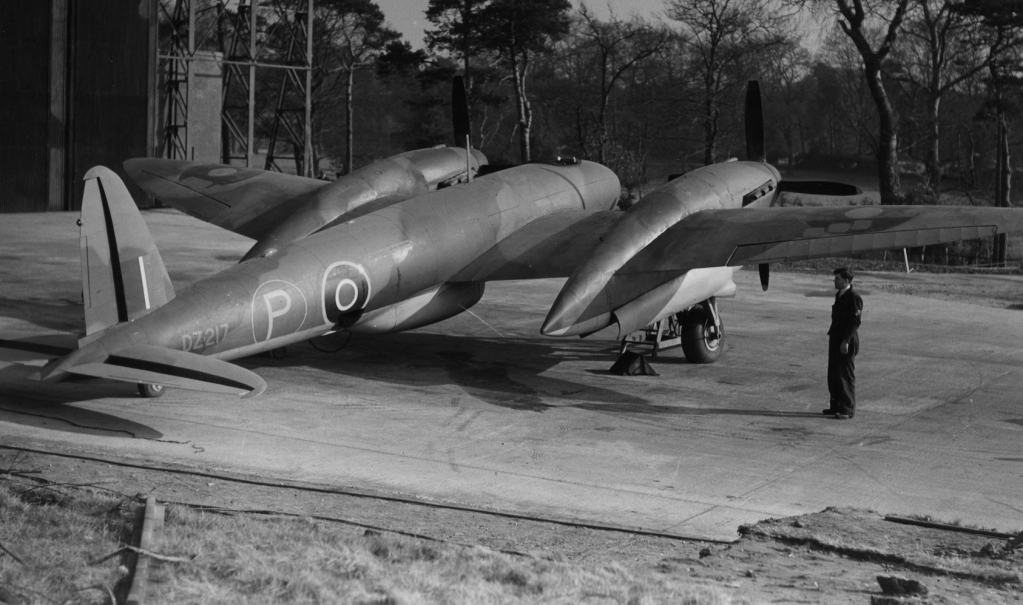

Vickers Type 432 (UK)

I have always been fascinated by how this design sits alongside the de Havilland Mosquito. In fact the 432 was known as the ‘Tin Mossie’ (the Mosquito was built primarily in wood) but the need for this fighter essentially just disappeared. One feature was the unusual method of construction used for its wing, which was known as ‘lobster claw’.

On 9th September 1941 Vickers received a contract for two prototypes, serials DZ217 and DZ223, of a new twin-engine fighter to operate at high altitude and to be fitted with a pressure cabin. The prototypes were built during 1942 but the first flight was delayed for a number of reasons, until DZ217 finally climbed into the air on 24th December. However, five days later the Ministry of Aircraft Production advised that only one prototype was to be completed and that all work on the second machine was cancelled.

The maximum level speed actually achieved by DZ217, in May 1943, was 380mph at 15,000ft, which was some way off the design estimate of 435mph at 28,000ft; however, 400mph was exceeded in a dive. The final flights were made in November 1944, the aircraft was never submitted for any official trials at Boscombe Down and DZ217 was eventually scrapped.

The Type 432 and the designs leading to it had showed undoubted promise, but the long period of time taken to produce hardware saw this evaporate away and no real effort was ever made to correct the aircraft’s faults. Consequently, it will never be known just how good this aircraft might have been. Vickers’ own war diary describes the 432 as ‘an interesting experiment which resulted in a dead end’.

Republic XP-72 (USA)

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was of course one of the great fighters of World War II. I think that the change of engine to produce the XP-72 did much to improve the fighter’s looks, but once again this alternative design also provides a fascinating comparison to the production P-47. In the case of the XP-72, the addition of contra-rotating propellers is an added interest to me.

The XP-72 was designed as a long-range high-altitude high-speed fighter. The American engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney had produced what would prove to be the last important reciprocating engine to be used by US military air arms before they moved on to turboprops and jets – the massive 28-cylinder turbo-supercharged R4360 Wasp Major. In 1943 some examples were made available as experimental units for prototype aeroplanes and one recipient was the Republic model AP-19, essentially a bubble-canopy P-47D fitted with an R4360 and two-stage supercharging, which received the Army Air Force designation XP-72. The wing and empennage were similar to the standard P-47D, but the airframe had been enlarged and the lower fuselage modified for a large underside air intake.

Two prototypes were ordered on 18th June 1943 and the type became known as the ‘Super Thunderbolt’ or ‘Ultrabolt’. It was intended to fit a dual-rotation (contra-rotating) propeller, but problems with the Aeroproducts fitting meant that the first prototype, serial 43-36598, first flew with a conventional Curtiss Electric 4-blade propeller. The second, 43-36599, did get the Aeroproducts 6-blade prop. 43-36598 made its maiden flight on 2nd February 1944 and the second XP-72 first flew on 26th June 1944; test pilot Carl Bellinger flew the prototypes. Incidentally, the 4-blade propeller on 43-36598 was possibly the largest ever fitted to a fighter – indeed, the propellers fitted to the two XP-72s were so big that, to avoid them hitting the ground, the pilots had to take off and to land in a three-point attitude!

The XP-72’s potential performance resulted in a contract in late 1944 for 100 P-72s. Production machines would receive the 3,650hp R4360-19 with a dual-rotation propeller, which it was estimated would give a top speed of 504mph at 25,000ft, and four 37mm wing cannon would replace the machine guns. Officially the fighter’s top speed was given as 490mph at 25,000ft and both prototypes achieved this figure. However, by the time the XP-72 flew, other versions of the P-47 and the North American P-51 Mustang escort fighters were flying high altitude operations over Germany. There was no need for another high-altitude piston fighter and the P-72 production order was cancelled in January 1945. In August 1946 one prototype (without its engine) went to an Air Scouts group on Long Island. The other XP-72 was scrapped.. A pity because this fighter was very fast indeed!

Keep Hush-Kit FREE for everyone by donating on the buttons this page, every donation helps Hush-Kit carry on this mad brilliant endeavour.

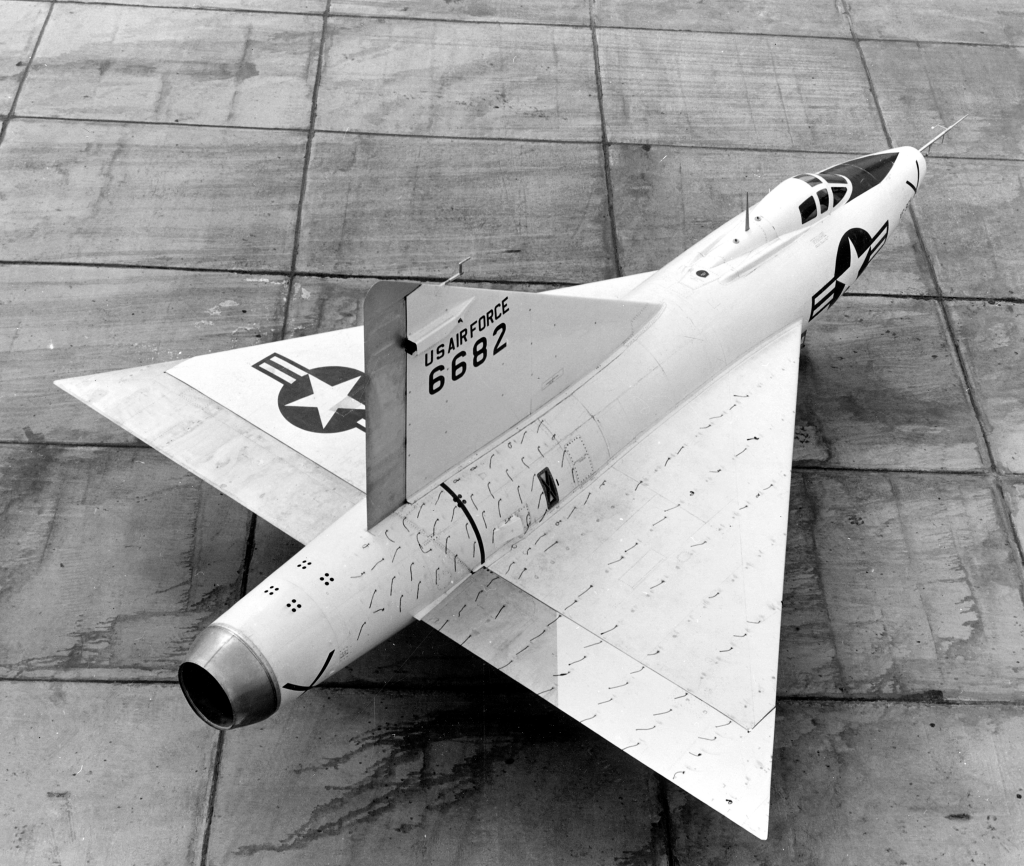

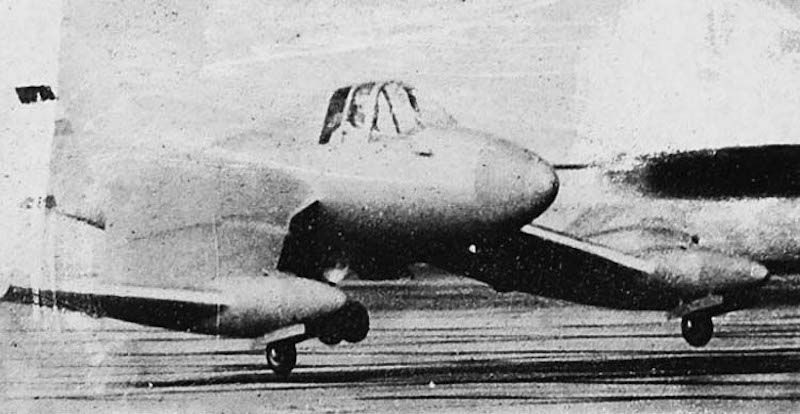

Convair XF-92 (USA)

Among the many superb-looking delta-winged jet fighters designed and flown worldwide, the Convair XP/XF-92 has always been something of a favourite to me, and yet it was not that good an aircraft. In August 1945 the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) issued a requirement for a high speed, high altitude, high performance interceptor. The winning design was the rocket-powered supersonic Model 7 project from Convair which was designated XP-92. Unfortunately, problems with the airframe design, its rocket motor, plus a move of factory from Downey to San Diego in the summer of 1947, all conspired to slow this programme down, and in August 1948 the XP-92 was cancelled.

However, work on a full size jet-powered flying model had started in September 1946 to evaluate the interceptor’s delta wing. Convair called this aircraft its Model 7002 and the USAAF allotted serial numbers 46-682 to 46-684 to three planned airframes. At first this aeroplane was officially designated XP-92A and received the name Dart but soon afterwards, when the USAAF became the US Air Force, it was retitled XF-92A after the old ‘pursuit’ designator had been replaced by F for ‘fighter’. Following the interceptor’s cancellation, the first XF-92A was retained for general research flying to assess the delta wing’s stability and control, to establish structural design criteria, and to determine the machine’s own performance; the second and third airframes were not built.

The designated XF-92A project pilot was Ellis D. ‘Sam’ Shannon who performed the 18-minute maiden flight on 18th September 1948, in the process making this machine the first delta wing aircraft to fly anywhere. But the pilot found that the aircraft was clearly underpowered and also that the control system was extremely sensitive to minute control stick deflections. On one occasion Air Force pilot Frank K. ‘Pete’ Everest pointed the XF-92A’s nose directly down in a dive from height and, using maximum engine thrust, he managed to reach supersonic speed, but he was barely able to get the aircraft to pass through the sound barrier. Figures recorded during this period included a maximum level flight Mach number of 0.85 at 21,000ft.

The lack of engine thrust was addressed by fitting a new engine, an Allison J33 which introduced an afterburner. This installation also necessitated a rear fuselage extension to house the new afterburner inside a longer and more cylindrical tail cone. Chuck Yeager flew the XF-92A’s first sortie with the new engine on 20th July 1951, but the results of trials flying overall were poor because the afterburner would continually flame out at heights above 38,000ft. A maximum true Mach number of 1.01 was obtained after diving for 7,000ft from an altitude of around 38,400ft. Later the XP-92A was used by NACA (the predecessor of NASA) for further trials and today it resides in the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB.

If you love cancelled aircraft, you should certainly pick up a copy of The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes, which features a wide variety of exotic military aircraft portrayed in superb new illustrations, among many other warplanes, interviews, articles and top 10s. You should also pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 2 today, which will be even better than the first volume. Keep Hush-Kit FREE for everyone by donating on the buttons this page, every donation helps Hush-Kit carry on this mad brilliant endeavour.

My experience in the Vietnam War taught me not to trust my Government

Extract from The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club (courtesy of author and Osprey Books)

As for many of my generation, the war in Vietnam and my participation in it changed my life completely. Forever.

- Thomas McKelvey Cleaver

Looking back, I divide my life in two parts: Before Tonkin Gulf, and After Tonkin Gulf. I will never, ever forget the moment in late September 1964, when I decided to stop in a bar on the main street of Olongapo, the “service town” outside the Subic Bay Naval Base, that I was passing to get out of the tropical sun. USS Pine Island, an ungainly seaplane tender that was flagship for the admiral’s command, of whose staff I was an enlisted member, had docked that morning for a break after our first deployment to Da Nang, following what we all knew was the first step to a war in Vietnam that involved us – the “Maddox Incident” as we in the Navy called it.

Inside, sitting at the bar, was my best friend from Navy boot camp, who I hadn’t seen since we had both gone through firefighting training at the San Diego Naval Station the year before while awaiting transport to our separate destinations in WestPac. His ship’s patch was on his shoulder: “USS Maddox.” I’d forgotten that was his destination.

Taking the seat to his left, I took note of the outline of the missing petty officer’s “crow” on his sleeve. The outline of holes where the crow had been sewn told its own story – he’d been busted. Recently. I bought us each a San Miguel, and answered his questions about what I’d been doing: I worked in the operations office on the staff of Commander Patrol Forces Seventh Fleet, which I noted had been Maddox’s operational commander at that event. He frowned at that. Another round of San Miguel was ordered, and it was my turn to question him. As delicately as I could, I asked “How’d that happen?” pointing at his sleeve.

“Got busted.”

I expected him to tell me he’d gotten a “captain’s mast” for coming back late from liberty, something that could happen to any of us and nothing to make a big deal of. No. He’d been court-martialed. Hmmm – a summary court was a little more serious, so I asked “what for?”

“Failure to obey a direct order.”

Now that was serious indeed.

“What order?”

“‘Open fire.’ Said ‘no’ three times.” Yikes!

And then, while he told me there had been no enemy torpedo boats attacking Maddox or Turner Joy that night I’d been awakened at 0200 hours as the duty yeoman in the operations office to take the FLASH message of the attack to the Chief of Staff, how he had been the senior fire control technician in the ship’s gunnery control tower and had three times refused to open fire with the six 5-inch guns he controlled, telling his captain each time that the only target out there in the darkness was the other American destroyer, my life changed forever.

Never again, after those minutes in that Olongapo bar, would I ever believe without proof anything said by any official of the government of my country, a country whose constitutional government I had sworn to protect against all enemies, foreign or domestic. Little did I know then that, after I got home the following year and returned to civilian life, I would spend the next seven years consumed by my opposition to the war I had learned that day was a lie.

I came to learn during those years that there is a profound difference between loving one’s country and supporting its government.

I have studied the Vietnam War in detail in the years since I returned home and told my father that first night back that “You know absolutely nothing about what’s really going on in that war.” That was the beginning of the Seven Years’ War of the Cleavers – with my father finally saying in 1987 that I had been right, during what turned out to be our last face-to-face conversation. It’s why I spent a considerable bit of time in the late sixties involved with the late Dr. Peter Dale Scott, who was dedicated to tracking down the witnesses to the lie that began what had come to be known as the “War of Lies” and discovering that what I had discovered that afternoon in an Olongapo bar was almost only the least of it. It’s why I ended up with a degree in History. It’s why I was overjoyed the day I laid hands on a copy of the “Pentagon Papers,” where for the first time I read an account of the event that changed my life that comported with the reality I had discovered.

It turns out that even now, 50 years later, there are secrets from that night still to be examined. Others have studied the Tonkin Gulf Incident, and it is now known that those “lights in the water” mistakenly identified as enemy torpedo boats were in fact the reflections of the moon and lightning flashes on the enormous school of flying fish that transits the Tonkin Gulf at that time of year. Lyndon Johnson was more right than he knew when he exclaimed, on being first informed of the event, that “those dumb, stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.” In that moment, he knew more about the war than all his advisors ever did.

One can nowadays ask Google the right questions, input an old code name, and be rewarded with a PDF of a document previously classified Top Secret, now declassified through the Fifty Year Rule, and find that they knew! They knew all the mistakes, all the missed opportunities, everything! They knew them and either let them continue or took actions that exacerbated them.

Perhaps the best news to come from that war is that the men who were in the cockpits of the MiGs, and their opponents in the cockpits of the Phantoms and Crusaders, have come to know each other personally, have visited each other in their homes, have become friends. They recognize and respect each other. Peace has been declared.

This book could not have been written without the active help of those who were there: Rear Admiral H. Denny Wisely from Fighter Squadron 114 (VF-114) and the war’s first years, Captain Roy Cash, Jr., who served in VF-33 in the middle years, and Commander Curt “Dozo” Dosé of VF-92 and Lieutenant Michael M. “Matt” Connelly of VF-96, who flew in 1972’s “new war.” Their willingness to go over their experiences in detail and to review the manuscript for accuracy was critical to completing this project. The late Don Davis, the Associated Press war correspondent who originally reported the “Higbee Incident,” provided essential information on the event that the Navy’s History and Heritage Command now claims never happened. Rear Admiral James A. Lair of Attack Squadron 22 (VA-22) as well as Captain Ken Burgess, Captain Timothy Prendergast, and Captain Richard Heinrich of VF-51, Lieutenant Commander William Crumpler of HC-1, and Admiral James W. Alderink, then commander of Air Group 21 aboard the USS Hancock, recalled their experiences during Operation Frequent Wind, the evacuation of Saigon in 1975, and the Mayaguez Incident.

Importantly, through Roy Cash and Curt Dosé, I was also put in contact with retired Lieutenant General Pham Phu Thai, who ended a 30-year career as deputy commander of the Vietnam People’s Air Force (VPAF), and retired VPAF Colonel Tu De, the last living participant in the Higbee Incident, who shared their experiences as young pilots of “the other side.” Dr. Nguyen Sy Hung, Historian of the VPAF and author of Aerial Engagements in the Skies of Vietnam Viewed From Both Sides, considered by American participants who have read it to be a far more accurate and honest account of events they were party to than official US sources, provided an English translation of this important book, without which it would not have been possible to write a history that puts both sides in the air together. After 50 years, it’s time to try to tell the whole story.

Examining any facet of the Vietnam War inevitably leads to the question, “Were there any lessons learned?” Sadly, a five-minute examination of the daily paper can quickly lead to the answer: no, no lessons were learned.

If there is a lesson, it is this by foreign policy analyst Adam Garfinkle, analyzing Vietnam and our wars since:

Finally but most important, U.S. expeditionary forces operating in any non-Western cultural zone are very unlikely to win a war at reasonable cost and timetable, employing levels of violence acceptable to the American people, unless the U.S. effort includes a serious effort to understand the country, and unless it has a local ally that is competent and legitimate in the eyes of the population it would rule. In none of these cases did those conditions apply.

This book is for those who cannot forget this history.

The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club: Naval Aviation in the Vietnam War available here

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes available here and volume 2 can be pre-ordered here

Is that a Russian warplane over your house?

A beginner’s visual identification guide

When Putin decides to invade your country it may prove useful to identify the warplanes he will send. With this idiot-proof guide, even you can learn how to tell a Flanker from a Foxhound.

Part one of three.

Over thirty years after the demise of the Soviet Union, almost all Russian warplanes are still Soviet in origin.

Europeans turn their noses up at twin tails, currently considering them a little gauche* – but the crass Americans and Russians love them. The most common twin fin aircraft in the Russian armed forces is the T-10 series, known to the West as the ‘Flanker’ and ‘Fullback’. This comprises the Sukhoi Su-27, 30, 32, 34 and 35. They are much larger than the very similar MiG-29 series, but if you are unable to see the scale lookout for a slender elegant curve from the front wing root to the nose. The MiG-29’s vertical tails also cant outwards whereas Flanker tails are almost vertical.

*not sure there’s been one since the 1950s Sea Vixen other than the half Swedish T-7, though the future may well see Western Europeans changing their tastes.

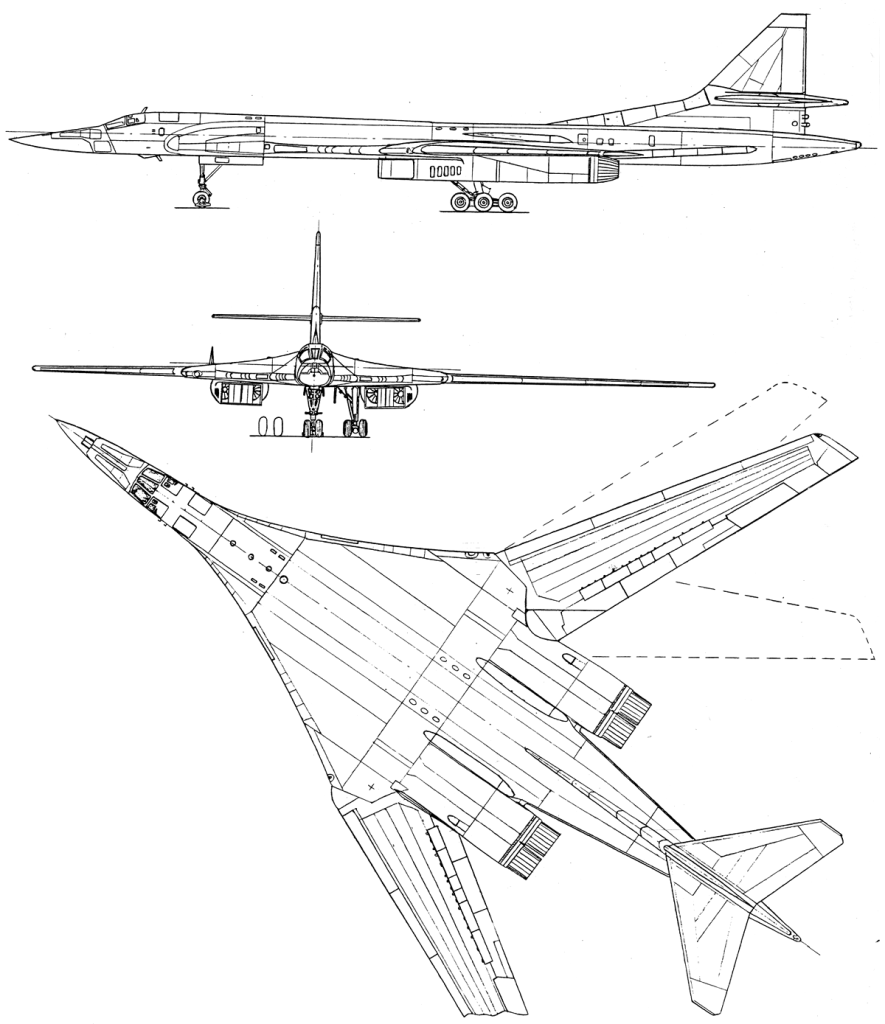

The Blackjack is a massive supersonic bomber, larger than the Backfire.

If the engines stick out of the armpit – it is a Blackjack.

- If the horizontal tail is mounted up on the tail like a crucifix – it is a Blackjack.

Telling the Blackjack from the American B-1B

The rear section of the Tu-160’s engine protrudes more from its armpits.

The inner wing section of the Tu-160 has a shallower sweep angle

- at moderate wing sweep there is a pronounced kink between the arms and the shoulders of the Blackjack.

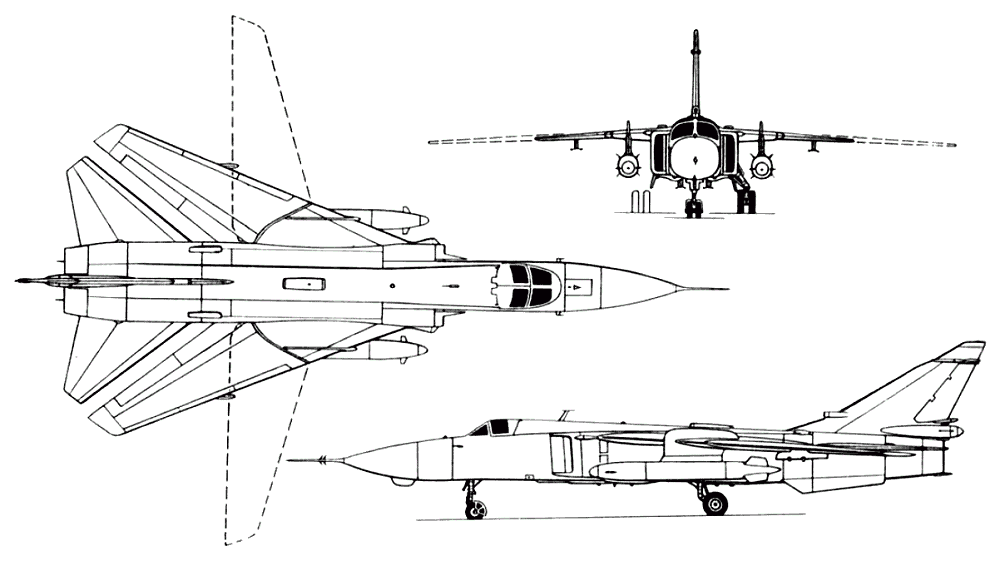

Sukhoi Su-24 ‘Fencer’

The easiest aircraft to confuse with the Su-24 is the Tornado.

-proportionally the Su-24s tail is shorter

- The Su-24 is more slender and less stubby

- The Su-24 has a side-by-side cockpit – so the windows look like a toenail from above as opposed to the Tornado’s windows that looks more like a tampon.

- The Su-24 is likely to have fuel tanks (looking like sausages) tucked closely under its armpits

Sukhoi Su-25

The most dangerous seat in a fixed-wing aircraft is that of a Su-25 in combat.

- The wide wings are not swept (though front edge is)

- Squat, chunky appearance

Sukhoi Su-57 ‘Felon’

Listen out for the distinctive scream

- The plan view looks like a fat ghost or clansman.

- Side view and front view very slim and pancake-like

- Not used directly in combat zone to avoid reputational damage from combat losses and or compromise of sensitive technology

MiG-31

–

Twin tails

- jet exhaust nozzles extend MUCH further back than the tail (unlike the F-15 and to lesser extent the Su-27)

- Big, beefy and blocky

- The cockpit canopy (the window section) is barely higher than the spine (unlike the F-15)

- The wingtips are parallel to the main body of the aircraft (the F-15’s are cut back)

- Unlike the MiG-29 and Su-27 there is no big channel between the engines

10 Reasons the Bristol Beaufighter was the hardest bastard in the sky

As brutish as the Mosquito was elegant, the Bristol Beaufighter’s huge contribution to winning the War is far too often overlooked. If aircraft had personalities, the Bristol Beaufighter belongs in that grand British tradition of irredeemably malevolent working-class thugs, from Bill Sykes to Ronnie Kray to Begbie to anyone played by Ray Winstone. It has not even a sliver of the beauty referenced in its given name. It was the hardest bastard in the sky.

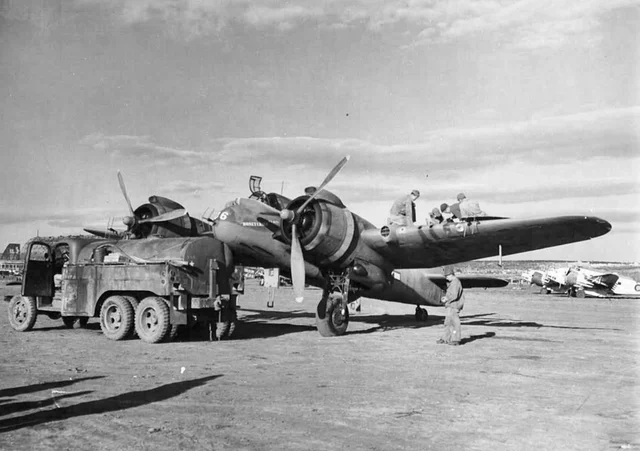

The classic image of a 272 Squadron Bristol Beaufighter VIF at Takali airfield, Malta.

10. Only cowards run

You wouldn’t ask Reggie Kray how fast he can run, would you? That would be taking a diabolical liberty. And the Beaufighter was just the same.

Arriving on the scene in Autumn 1940, the Beaufighter could scrape past 320mph. It was scarcely faster than the fastest of the German medium bombers, and way behind the contemporary Bf 109 and the Luftwaffe’s own heavy fighter, the Bf 110, which was already being found out as easy meat* for Spitfires and Hurricanes.

Four years later on, and despite 1000 horse-power more and over a dozen upgrades, the Beaufighter was still struggling to scrape past 320mph, despite operating in a world of ever faster 109s, Macchis and Focke-Wulfs, and the existence of its wooden friend and rival Mosquito which raised the bar above 400mph. The Beaufighter defied air performance gravity, which many other aircraft types, including its predecessor the Blenheim, couldn’t. Its speed simply didn’t matter, as it was bastard tough.

*Though there may be more to this story