My Top 10 Cancelled Warplanes By Tony Buttler

My Top Ten Projects, Cancelled Aircraft and Experimental Prototypes

Quite some time ago Hush-Kit’s Joe Coles kindly asked me to write a piece for the Hush-Kit site. I apologise for taking so long, but this is the result.

Joe asked for my thoughts on my Top 10 cancelled and abandoned aircraft – my clear favourites, the types that fascinate me the most, and the most obscure aircraft I can think of. To be honest that was not the easiest thing to do. I have a lot of favourites among the cancelled and rejected projects and to eliminate so many was a test in itself. But what follows is a good cross-section of those types which I have enjoyed writing about. Most were built and flown but one, the Hawker P.1083, only got as far as an incomplete prototype.

If you love cancelled aircraft, you should certainly pick up a copy of The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes, which features a wide variety of exotic military aircraft portrayed in superb new illustrations, among many other warplanes, interviews, articles and top 10s.

Over the years I have written a good deal about bombers and ground attack aircraft, but for all of my life it has been the fighter and interceptor from the mid-1930s onward, and those research types associated with this category, which have interested me the most. So, with apologies to bomber fans, almost all of the aircraft which follow were in general associated with air defence, interception and dogfighting. And I’m afraid my choice has also been governed by the appearance or ‘good looks’ of each type, because to be a favourite for me an aeroplane design needs to be able to catch one’s eye.

A outcome of this last point is that Hawker Aircraft have contributed three different types to the list. I have recently prepared a lecture for the Hawker Association covering the one-off test bed and experimental prototypes proposed and built by this firm, and while putting it together I realised that Hawker must have designed more beautiful fighter aircraft than perhaps any other fighter design team in the world – I would suggest that North American Aviation is the one that comes nearest – what do you think? I could easily have included the Hawker Tempest I and the Napier-Sabre-powered Hawker Fury prototypes here as well!

I must raise one point about making judgements on cancelled aircraft projects, a point which was first suggested by a great friend of mine. And that is there is a tendency to always look at ‘what might have been’ with dreamy eyes and without looking at the situation and the hard facts. He cited the 1950s British Supermarine Swift jet fighter, a programme which perhaps should have been killed off early on. Had the latter been the case, there are undoubtedly aviation historians and authors who would have written that it was a disastrous decision, and that the Swift would have been a superb fighter! In fact, as a pure fighter it was a failure and it was the later fighter-reconnaissance FR.Mk.5 variant which would give the Swift something of a modest Service career.

Aircraft projects and programmes can be cancelled through many reasons – cost, modern technology making them obsolete (like the jet replacing the piston engine) or that simply they were just no good. Each specific case will have more baggage ‘attached’ to it in terms of situation and background than many might realise. Don’t forget as well that the UK does not have, not by any means, the monopoly on cancelled aircraft projects.

All of the types described below date from the 1940s and 1950s, for me perhaps the most exciting time in aviation history. Do please remember that this is a personal choice. I am sure all of you reading the text that follows would pick an entirely different group of favourites, but I hope you will agree that there are some interesting and fascinating aeroplanes here. Thank you for taking a look.

Tony Buttler June 2023

FMA IAe 30 Ñancu (Argentina) 1948

One of my all-time favourite fighter-type aeroplanes has to be the de Havilland Hornet and Sea Hornet, but these had a successful production run and good careers and so do not qualify for inclusion here. The Hornet had followed the wartime Mosquito and it is quite extraordinary I think that Argentina built two aircraft types that were not only direct equivalents to, but also looked very similar to, these British machines. Just over 100 examples of the IAe 24 Calquin attack bomber, a Mossie look-alike, were built, but only one IAe 30 Ñancu would be flown.

After WW2 many prominent designers and pilots from Germany and Italy would move on to Argentina to work for the new aircraft industry based there. After the Mosquito-like Calquin, it was perhaps no surprise that Italian Cesare Pallavecino (FMA Chief Designer from late 1946), when asked to design a high speed twin-engine escort fighter to protect the Air Force’s Avro Lancaster and Lincoln bombers, would produce something which looked much like the Hornet. In fact the Ñancu was not nearly so similar to the Hornet as the Calquin was to the Mosquito, but came close in the wing and nacelle areas and it used the same engines.

The Ñancu was one of the last piston-engined fighters built anywhere in world. Its name, pronounced ‘nyanku’, referred to an Eagle which inhabited the Patagonian plains. It was an all-metal aircraft with a triangular or ‘pear-shaped’ cross section (the Hornet had a more oval fuselage) and again, like the Hornet, Ñancu’s Rolls-Royce Merlin 134/135 engines were handed (i.e. opposite rotating). It was to have four 20mm cannon mounted in the lower nose, although the prototype never received any weapons but instead featured a transparent nosecone. The first flight took place on 17th July 1948 with the aircraft piloted by IAe chief test pilot Capt Edmundo Osvaldo Weiss.

Comments on Ñancu’s performance proved very favourable and there were few problems. In all 210 production aircraft were planned but progress was slow. However, Weiss did record over 550mph in a dive and he reached a speed of 485mph on the level. Due to ever increasing financial problems, however, the production run was never started and the Ñancu was cancelled late in April 1949. The only flying prototype was lost in a landing accident later that year, while work on a second machine was started but never completed. Ñancu was an excellent aircraft but unfortunately arrived at the same time as IAe’s Pulqui II jet fighter, and so was rather pushed out of the picture.

Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow (Canada) 1958

I guess one could call this dramatically impressive interceptor fighter the ‘Canadian TSR.2’, because the abandonment of this extraordinary machine is probably just as controversial as was the dropping of the British Aircraft Corporation TSR.2 strike aircraft in 1965. In April 1953 the Canadian Air Force issued a demanding specification which requested a sustained speed of Mach 1.5. The Avro Canada company responded with a very large delta wing design, prototypes were ordered in December 1953 and in 1954 the type was designated CF-105, but it was not officially named Arrow until early in 1957. In service it was to be powered by two home-grown Iroquois jet engines, but the first examples would have American Pratt & Whitney J75 units.

The first of five prototypes first flew on 25th March 1958. The biggest problems centred on the development of the weapon system and the ever growing cost, eventually pressure began to build on the project and its future became uncertain. The possibility of overseas customers might have helped and the CF-105 was examined by both the United States and the United Kingdom, with much interest coming from the British RAF. But no orders were forthcoming.

Gradually the Arrow became a very political aeroplane with much discussion over its cost, and also if it was really needed. The project was finally cancelled on 20th February 1959 in a move which also destroyed a substantial part of Canada’s aviation industry; Avro Canada went out of business and the CF-105 assembly line, tooling and the existing airframes and engines were ordered to be destroyed.

At cancellation five CF-105s had flown and the flight test programme overall had progressed smoothly with relatively few aerodynamic problems. A total of 70 hours airtime had been accumulated and Mach 1.95 had been reached at a height of 42,000ft. For Canada’s future air defence the Arrow was replaced by the American McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo fighter and the Boeing Bomarc surface-to-air missile, again controversial acquisitions.

Hawker P.1081 (UK)

To be honest the Hawker P.1052 and P.1081 need no introduction – these are very well known aeroplanes. They were built purely as research aircraft to investigate the benefits of swept back wings and initially two Rolls-Royce Nene-powered P.1052s were ordered as swept wing versions of the straight wing Hawker P.1040/Sea Hawk naval fighter, but retaining that type’s straight tailplane. The first, VX252, first flew on 19th November 1948 piloted by Hawker test pilot Trevor ‘Wimpy’ Wade and it proved a success.

In due course the second P.1052, VX279, was heavily modified with an all-through jet pipe and a swept tail and fin to become the P.1081. These are lovely aircraft and the P.1081 in particular has always been a favourite for me since it looked splendid. As modified, Wade took VX279 on its second maiden flight on 19th June 1950 and it was displayed at that year’s Farnborough Show in September. But, tragically, on 3rd April 1951 Wade was killed when the P.1081 was lost in a crash, the reasons for which have never been fully established. Nevertheless, the P.1081 can be considered as the final link between the Sea Hawk and what would become the gorgeous and hugely successful Hawker Hunter, another of my all-time favourites.

Hawker P.1083 (UK)

The P.1083 was an attempt to produce a Hawker Hunter capable of supersonic flight on the level, a move which basically involved fitting more highly swept wings, set at an angle of 50°, to the original fuselage. A full go-ahead was given by the Air Ministry on 12th December 1951, and in April 1952 a new Specification was issued to cover the design of the ‘Hawker Interceptor Fighter’ fitted with a reheated Rolls-Royce Avon RA.14R engine. However, in early April 1953, well into the manufacture of the prototype, the Air Staff requested that the P.1083 should now be armed with the de Havilland Blue Jay (Firestreak) air-to-air missile as its primary weapon, which then brought problems with a lack of space inside the airframe for radars and other equipment. The P.1083 had originally been developed as an improved performance Hunter and was to be armed with guns only – it was not intended to be a guided weapon carrier.

A Ministry memo dated 9th June 1953 declared that, thanks to previous flight test problems experienced with the Hunter, and coupled with the difficulty of fitting reheat to the engine and the lack of room for extra fuel and equipment inside the P.1083, the supersonic aircraft was now to be cancelled and work was to cease forthwith (at this stage it was also considered that the Hunter made a less attractive project than the rival Supermarine Swift). As a consequence Hawker’s design team spoke to Rolls-Royce about fitting the RA.14 into the standard Hunter airframe and in August the Air Ministry agreed that the firm should proceed with a non-reheat version of the aircraft with this larger engine. In due course the front and centre fuselage and the tail from the cancelled P.1083 prototype, serial WN470, were used to construct the Hawker P.1099 serial XF833, which became the prototype for the Hunter F.Mk.6 series. As such it first flew on 23rd January 1954.

Hawker P.1109 (UK)

During the mid-1950s studies had shown that, with the increased engine power of the Mk.6 Hunter, the radar/missile combination of AI.Mk.20 and Blue Jay could be fitted to the standard subsonic fighter to provide an increased capability without any loss of performance. Hawker was asked to do a study and the firm called the new version the P.1109. It would carry only two guns to reduce the nose weight and the most visible external change was the nose shape which increased the length by about 3ft. The standard F.Mk.6 Avon engine was retained.

In May 1956 the Hunter/Blue Jay programme was officially cancelled, but the Ministry of Supply encouraged Hawker to continue with it on a private basis. It was agreed that the firm would equip and fly one aircraft fitted with Blue Jay missiles within a three aircraft programme. Hawker would clear the in-flight handling before de Havilland Propellers (the weapon manufacturer) would take over the aircraft for firing trials. Serials WW594, WW598 and XF378 were converted to this configuration in 1956, but only XF378 was fully equipped with the complete Firestreak plumbing and pylons to take the missiles. P.1109A was the designation given to the aerodynamic test aircraft without any missiles, P.1109B was the full conversion.

The Green Willow AI.Mk.20 fire control radar was intended for single-seat fighters but it was manufactured only in a short run; possibly no more than five examples. It was developed as a back up for the AI.Mk.23 then being designed for the English Electric P.1 (Lightning) and it was never used operationally.

XF378 first flew with two Blue Jays and an AI.20 radar installation on 12th September 1956. During trials the highest achieved airspeed by a clean P.1109 was 620 knots and the highest altitude 55,000ft; the maximum recorded Mach number was 1.16 in a steep dive from 51,000ft. Overall, the general handling did not appear to have been appreciably affected by the modified nose. A dive from 48,000ft down to 25,000ft enabled the ‘armed’ aircraft to reach Mach 1.09, and the full throttle level speed at low altitude was 605 knots at 2,000ft. The general handling of the P.1109B XF378 with two Blue Jays was very satisfactory.

XF378 attended the Farnborough Show in September 1957, by which time the missile trials programme was pretty well done. However, the three airframes did find other roles. The two P.1109As moved on to RAF West Raynham for special trials and WW598 also spent time with the Royal Radar Establishment at Defford and with RAE Bedford, before going to RAE Farnborough. XF378 was written off in 1959 after a fuselage fire.

At the Air Fighting Development Squadron at West Raynham it was found that a standard Mk.6 Hunter flying at about 50,000ft experienced great difficulty in keeping up with the P.1109 at that height; the latter still had plenty in hand and in due course could leave the normal aircraft behind pretty quickly.

The Hunter P.1109 programme was an interesting and worthwhile exercise and was regarded by many as the best looking of all Hunters. Certainly by me!!

Short Sturgeon (UK)

The version of this aircraft which I am referring to here is the original torpedo bomber in prototype form, just two airframes in total, and not the target tug versions that followed. Apart from again looking attractive in my eyes (especially for a bomber or attack type), the Sturgeon is also of great interest in that it had contra-rotating propellers on each engine, which removed the problem of torque and swing for twin-engine aircraft taking off from and landing on aircraft carriers. As such it makes an interesting comparison to the de Havilland Mosquito and Hornet. The former had single propellers rotating in the same direction, which meant that swing to the right had to be countered during the take-off run. The Hornet had solved this problem by having ‘handed’ engines – that is the single propellers on each unit rotated in opposite directions. The Sturgeon’s contra-props provided another solution to the problem of swing.

An Instruction To Proceed was given to Shorts in October 1943 for a twin-Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered project which was eventually called the S.A.1 Sturgeon. Three S.Mk.I prototypes, RK787, RK791 and RK794 were ordered and RK787 made its maiden flight on 7th June 1946. The Sturgeon was essentially designed for operations in the Pacific as part of preparations for the final drive against Japan, but after that conflict had ended the Navy was left with a new bomber and nowhere to use it. As a result the bomber Sturgeon did not enter production, but before the end of the war it was turned into a humble target-tug as the TT.Mk.2 variant. The third S.A.1 prototype, RK794, was modified to act as the prototype. Reserialled VR363, it first flew on 18th May 1948 and 24 production aeroplanes followed.

Supermarine Spiteful and Seafang (UK)

One of the fastest piston fighters ever! And one reason why these types interest me is because the later Rolls-Royce Griffon-powered versions of the Spitfire and Seafire are my favourites from that tremendous family of fighters and the Spiteful and Seafang were concurrent types which, with their tapered laminar flow wings, offered a direct comparison to the Spit’s elliptical wing. In the end the elliptical type would still prove to be as good as the Spiteful wing, which in itself shows just how good designer R.J. Mitchell’s original Spitfire wing had been back in the mid-1930s when it was first designed.

In order to improve the Spitfire’s rolling characteristics Supermarine had been asked by the Ministry in 1942 to produce a new wing. At the same time it was also considered advantageous to have a laminar flow section on this wing and the result was known as the laminar flow wing or, on occasion, the ‘thin wing’. Theoretically the laminar flow wing was designed to move the boundary layer transition point further aft on the wing surface so that the point at which the airflow over the wing became turbulent was delayed, and drag was thus reduced. The main benefits were expected to be an increased performance from the laminar flow, the avoidance of compressibility effects and improved rolling manoeuvrability from the smaller span. Compressibility was a growing problem caused by flying at speeds ever nearer to the speed of sound, and ever more powerful engines meant that the aerodynamics needed to cater for this.

Three aircraft were ordered and Supermarine called the new aircraft its Type 371. There were discussions for a new name and by March 1944 production 371s were being called ‘Valiant’ by the Ministry, but the new fighter was eventually named Spiteful. The first aircraft to fly with the new wing, Spitfire Mk.XIV NN660 converted as a hybrid Spiteful prototype, made its first flight on 30th June 1944. The first true prototype, NN664, completed to full production standards, flew on 8th January 1945, but subsequent flight trials indicated that the hoped for advances over the Spitfire had not been achieved.

Tests on the modified Spitfire allowed a direct performance comparison to be made and the laminar wing did produce an increase in speed over the standard Spitfire wing, but it was disappointingly below the figure expected. Also, any slight degree of surface roughness, even from an impacted insect, could markedly reduce the speed. In addition the new version displayed poor stalling characteristics and more adverse compressibility characteristics than had the old elliptical wing.

Due to cutbacks brought about by the end of the war only 17 Spitefuls were completed from a planned run of 650 but several were used to improve the laminar wing’s aerodynamics, or to test alternative powerplants. One, RB518, recorded a speed of 494mph at 27,500ft, the highest speed ever achieved by a British piston-powered aeroplane.

In October 1943 Supermarine began to consider fitting the laminar wing to the Seafire and proposed this as the private venture Type 382. Initially this was not taken up but interest from the Admiralty began to grow and eventually a naval version of the Spiteful, called the Seafang, was ordered. Spiteful RB520 was fitted with a hook and flew in early 1945 as an interim Seafang prototype, but the first true prototype was VB895. A total of 150 Seafangs were planned but just eight were completed.

Vickers Type 432 (UK)

I have always been fascinated by how this design sits alongside the de Havilland Mosquito. In fact the 432 was known as the ‘Tin Mossie’ (the Mosquito was built primarily in wood) but the need for this fighter essentially just disappeared. One feature was the unusual method of construction used for its wing, which was known as ‘lobster claw’.

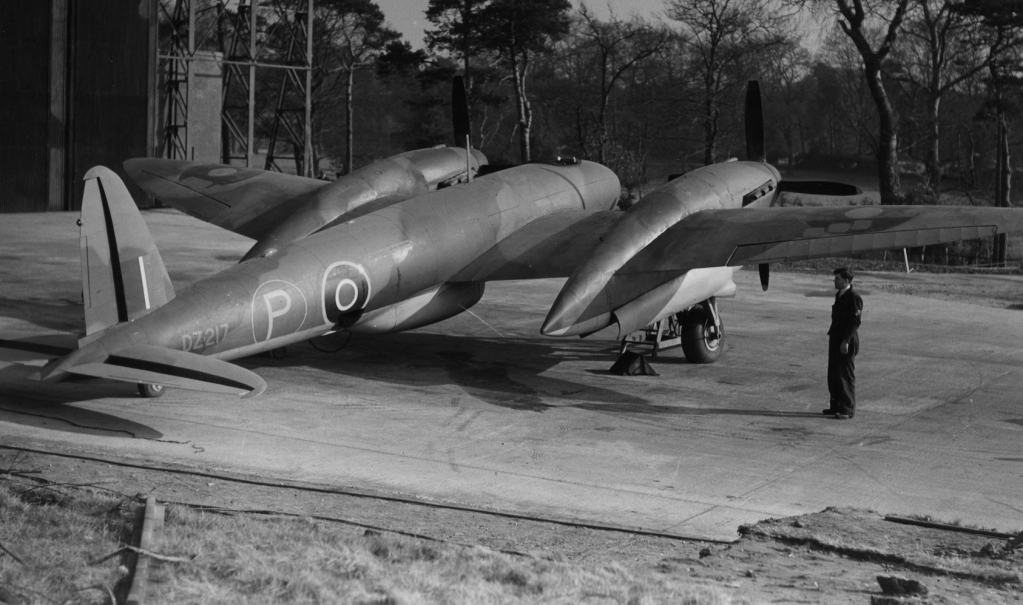

On 9th September 1941 Vickers received a contract for two prototypes, serials DZ217 and DZ223, of a new twin-engine fighter to operate at high altitude and to be fitted with a pressure cabin. The prototypes were built during 1942 but the first flight was delayed for a number of reasons, until DZ217 finally climbed into the air on 24th December. However, five days later the Ministry of Aircraft Production advised that only one prototype was to be completed and that all work on the second machine was cancelled.

The maximum level speed actually achieved by DZ217, in May 1943, was 380mph at 15,000ft, which was some way off the design estimate of 435mph at 28,000ft; however, 400mph was exceeded in a dive. The final flights were made in November 1944, the aircraft was never submitted for any official trials at Boscombe Down and DZ217 was eventually scrapped.

The Type 432 and the designs leading to it had showed undoubted promise, but the long period of time taken to produce hardware saw this evaporate away and no real effort was ever made to correct the aircraft’s faults. Consequently, it will never be known just how good this aircraft might have been. Vickers’ own war diary describes the 432 as ‘an interesting experiment which resulted in a dead end’.

Republic XP-72 (USA)

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was of course one of the great fighters of World War II. I think that the change of engine to produce the XP-72 did much to improve the fighter’s looks, but once again this alternative design also provides a fascinating comparison to the production P-47. In the case of the XP-72, the addition of contra-rotating propellers is an added interest to me.

The XP-72 was designed as a long-range high-altitude high-speed fighter. The American engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney had produced what would prove to be the last important reciprocating engine to be used by US military air arms before they moved on to turboprops and jets – the massive 28-cylinder turbo-supercharged R4360 Wasp Major. In 1943 some examples were made available as experimental units for prototype aeroplanes and one recipient was the Republic model AP-19, essentially a bubble-canopy P-47D fitted with an R4360 and two-stage supercharging, which received the Army Air Force designation XP-72. The wing and empennage were similar to the standard P-47D, but the airframe had been enlarged and the lower fuselage modified for a large underside air intake.

Two prototypes were ordered on 18th June 1943 and the type became known as the ‘Super Thunderbolt’ or ‘Ultrabolt’. It was intended to fit a dual-rotation (contra-rotating) propeller, but problems with the Aeroproducts fitting meant that the first prototype, serial 43-36598, first flew with a conventional Curtiss Electric 4-blade propeller. The second, 43-36599, did get the Aeroproducts 6-blade prop. 43-36598 made its maiden flight on 2nd February 1944 and the second XP-72 first flew on 26th June 1944; test pilot Carl Bellinger flew the prototypes. Incidentally, the 4-blade propeller on 43-36598 was possibly the largest ever fitted to a fighter – indeed, the propellers fitted to the two XP-72s were so big that, to avoid them hitting the ground, the pilots had to take off and to land in a three-point attitude!

The XP-72’s potential performance resulted in a contract in late 1944 for 100 P-72s. Production machines would receive the 3,650hp R4360-19 with a dual-rotation propeller, which it was estimated would give a top speed of 504mph at 25,000ft, and four 37mm wing cannon would replace the machine guns. Officially the fighter’s top speed was given as 490mph at 25,000ft and both prototypes achieved this figure. However, by the time the XP-72 flew, other versions of the P-47 and the North American P-51 Mustang escort fighters were flying high altitude operations over Germany. There was no need for another high-altitude piston fighter and the P-72 production order was cancelled in January 1945. In August 1946 one prototype (without its engine) went to an Air Scouts group on Long Island. The other XP-72 was scrapped.. A pity because this fighter was very fast indeed!

Keep Hush-Kit FREE for everyone by donating on the buttons this page, every donation helps Hush-Kit carry on this mad brilliant endeavour.

Convair XF-92 (USA)

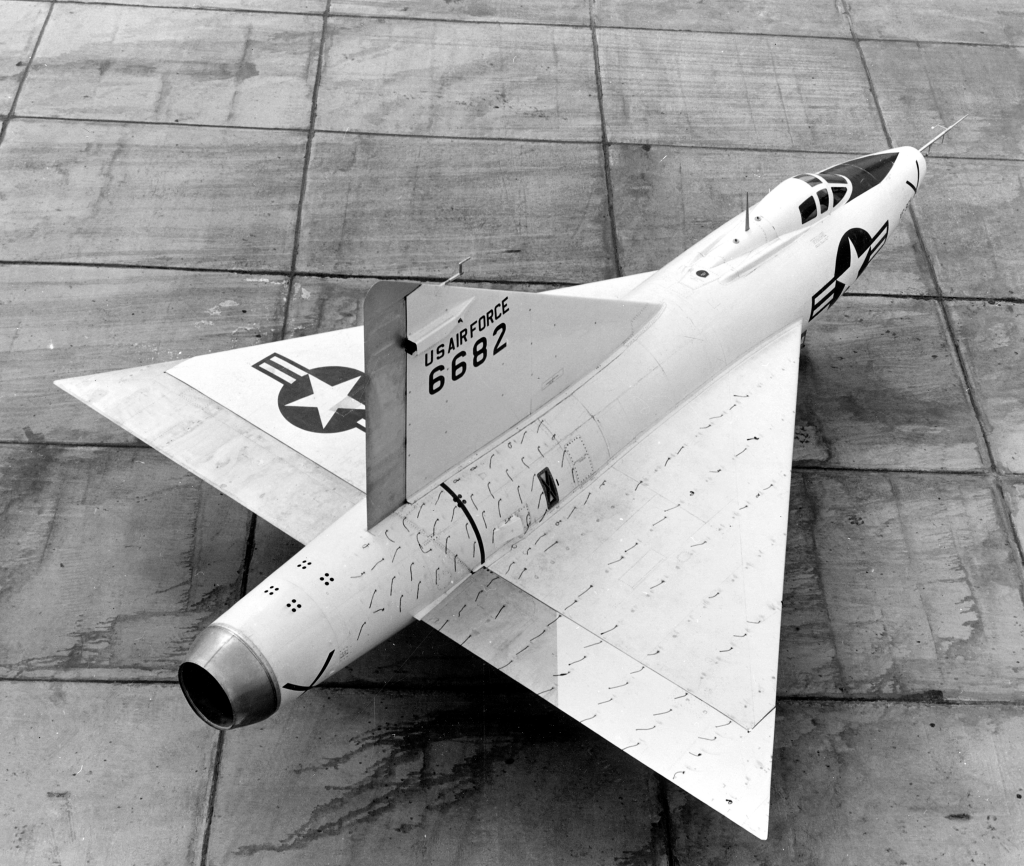

Among the many superb-looking delta-winged jet fighters designed and flown worldwide, the Convair XP/XF-92 has always been something of a favourite to me, and yet it was not that good an aircraft. In August 1945 the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) issued a requirement for a high speed, high altitude, high performance interceptor. The winning design was the rocket-powered supersonic Model 7 project from Convair which was designated XP-92. Unfortunately, problems with the airframe design, its rocket motor, plus a move of factory from Downey to San Diego in the summer of 1947, all conspired to slow this programme down, and in August 1948 the XP-92 was cancelled.

However, work on a full size jet-powered flying model had started in September 1946 to evaluate the interceptor’s delta wing. Convair called this aircraft its Model 7002 and the USAAF allotted serial numbers 46-682 to 46-684 to three planned airframes. At first this aeroplane was officially designated XP-92A and received the name Dart but soon afterwards, when the USAAF became the US Air Force, it was retitled XF-92A after the old ‘pursuit’ designator had been replaced by F for ‘fighter’. Following the interceptor’s cancellation, the first XF-92A was retained for general research flying to assess the delta wing’s stability and control, to establish structural design criteria, and to determine the machine’s own performance; the second and third airframes were not built.

The designated XF-92A project pilot was Ellis D. ‘Sam’ Shannon who performed the 18-minute maiden flight on 18th September 1948, in the process making this machine the first delta wing aircraft to fly anywhere. But the pilot found that the aircraft was clearly underpowered and also that the control system was extremely sensitive to minute control stick deflections. On one occasion Air Force pilot Frank K. ‘Pete’ Everest pointed the XF-92A’s nose directly down in a dive from height and, using maximum engine thrust, he managed to reach supersonic speed, but he was barely able to get the aircraft to pass through the sound barrier. Figures recorded during this period included a maximum level flight Mach number of 0.85 at 21,000ft.

The lack of engine thrust was addressed by fitting a new engine, an Allison J33 which introduced an afterburner. This installation also necessitated a rear fuselage extension to house the new afterburner inside a longer and more cylindrical tail cone. Chuck Yeager flew the XF-92A’s first sortie with the new engine on 20th July 1951, but the results of trials flying overall were poor because the afterburner would continually flame out at heights above 38,000ft. A maximum true Mach number of 1.01 was obtained after diving for 7,000ft from an altitude of around 38,400ft. Later the XP-92A was used by NACA (the predecessor of NASA) for further trials and today it resides in the USAF Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB.

If you love cancelled aircraft, you should certainly pick up a copy of The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes, which features a wide variety of exotic military aircraft portrayed in superb new illustrations, among many other warplanes, interviews, articles and top 10s. You should also pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 2 today, which will be even better than the first volume. Keep Hush-Kit FREE for everyone by donating on the buttons this page, every donation helps Hush-Kit carry on this mad brilliant endeavour.

“The designated XF-92A project pilot was Ellis D. ‘Sam’ Shannon who performed the 18-minute maiden flight on 18th September 1948, in the process making this machine the first delta wing aircraft to fly anywhere.” What about the Payen PA-22 which flew in 1942?

Didn’t the PA-22 have both delta and straight wings with its set if straight wings forward of the delta?