Category: Uncategorized

I was the first foreign pilot to fly the Mach 2.8 MiG-31 interceptor, here’s my story: By Air Marshal Anil Chopra (Retd)

Weighing the same as a M60 main battle tank and capable of flying 600mph faster than an F-16, the Russian MiG-31 is an absolute beast of an interceptor. Cloaked in secrecy, few outsiders have flown in the cockpit of this monstrous defender. Air Marshal Anil Chopra PVSM AVSM VM VSM (Retd) was given privileged access to the world’s fastest armed aircraft, here he describes this incredible experience to Hush-Kit.

“I felt I was sitting atop a missile-head in a high-speed interception.”

“The date was 28 May. Average daytime temperatures in May in Nizhnie Novgorad are around 22℃. Airfield elevation was 256 ft. The take-off and landing were done by the front pilot. The rear cockpit is used mostly as Weapon System Officer (WSO) station, though it has a control column to fly in case of an emergency requirement. There was nothing peculiar about the take-off. The frontal view through the periscope was good. I had used the periscope earlier on MiG-21UB (trainer) and on the MiG-23UB. So, I was quite comfortable. However the side view was minimal as the large front canopy left little place for Perspex for the second cockpit. I tried to visualise if the second pilot could easily land from the rear seat. Compared to a Su-30MKI it is surely more uncomfortable.”

Why did you try the MiG-31?

“I was the team leader of the Indian Air Force (IAF) MiG-21 Upgrade ‘Bison’ project in Russia from mid-1996 to the end of 2000. The design and development work was carried out at the Mikoyan Design Bureau in Moscow’s (OKB-155, Experimental Design Bureau 155). Our location was at RAC ‘MiG’, 6, Leningradskoye Shosse, Moscow. In 1995, Mikoyan OKB had merged with two production facilities to form the Moscow Aviation Production Association MiG (MAPO-MiG). Rostislav A. Belyakov, was still the father figure. I had an opportunity to meet him.”

“Two MiG-21Bis Aircraft had been sent from India for the design and development project. These aircraft were in positioned at the Sokol plant in Nizhnie Novgorod, where they were to be stripped and rebuilt after receiving the final design drawings from the Moscow Design Bureau. Sokol was also where the MiG-31 was being built. Our team used to visit the Sokol plant regularly from 1997, nearly once a month, for progressing the work on our two aircraft. Two of our officers were later permanently at Sokol for the flight testing of the Bison. The Director General of the plant, V Pankov mentioned to me about the MiG-31 and said that the Russians had been proposing the MiG 31 for sale to India. He said that they had given details to both the Government of India and to the Indian Air Force, but had not received any response or interest. I asked them to show us the aircraft, and if they had no problem, then I could get a chance to fly it. In Russian armament industry the general dynamics were still of the Soviet era. It took him some time to get approvals for me to fly in the rear seat of the MiG-31. They also told me that I was to be the first pilot from a foreign country to fly a MiG-31. They gave me a certificate to that effect, which is currently lying misplaced somewhere in my boxes. It was a demonstration flight and not a test flight. The basic aim was to show case the long range radar and to demonstrate high speed and acceleration. The date fixed was 28th May 1999. That was also the day the deputy head of India’s Mission in Moscow was on her first official visit to the Sokol plant. Ms Nirupama Rao was later India’s foreign secretary and India’s Ambassador to USA.”

Where did you fly it?

“The flight was made in the Sokol Aircraft Plant in Nizhniy Novgorod, which was formerly called Gorky. The plant was a manufacturer of MiG fighters. It was reportedly founded in 1932 and was once known as ‘Aviation Plant 21’, named after Sergo Ordzhonikidze. During 45 years of serial production the plant had manufactured about 13,500 combat aircraft. We were told that at its peak, they use to make close to 200 MiG-21s a year. But after the collapse of Soviet Union, and in the absence of significant orders from the Russian Air Force Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS), the production had gone down. The Indian MiG-21 upgrade was a significant order. Also, the plant used to make around 10-12 MiG 29 two-seaters in a year. There were nearly 15,000 employees. Their salaries were very low in the mid 1990s. Most of the sales and money earned from armaments was controlled directly from Moscow. All foreign contracts were through Rosvooruzhenie (later Rosoboronexport), the sole state intermediary agency for Russia’s exports/imports of defence-related and dual use products, technologies and services. We were told that the entire plant, including salaries could be run through the sale of just two MiG-29s. It was clear that the aircraft sale price was very high and basic production costs and salaries were very low. The high mark-ups of defence equipment prices are true in all countries. For some exported components, the price mark-up could be a 100 times. Many smaller plants that were the real original equipment manufacturers (OEM) of the components or sub-systems, wanted to sell spares directly to India, but the Russian government control was never released and with the result that the bulk of the profits went to Moscow.”

Interview with Indian Air Force MiG-29 pilot here

Russian people take a little time to make friends, but once they become one, they are great friends. There were many very senior technicians in the plant who had been to India in 1960s to help set up the MiG plant at Nasik. They had fond memories and spoke about the great time they had in India, and how they loved Indians. They also remembered the great Indian Old Monk Rum. We arranged to get some from India for them.

The production facility was next to the airfield (also known as Sormovo airfield), which was also the civil airport. For a long time, the plant was considered the most important industrial enterprise and main employer of the region. In those hard days, the plant was making many aluminium and other alloy based products, like river boats, frames for doors and windows, and even metro coach shells. We have heard that in later years they even encouraged flight tourism for MiG-29 to generate additional income.”

General Capability Briefing by the Russian Designers

“The MiG-31BM that I was to fly was reportedly a multirole version with partially upgraded avionics, new multimode radar, HOTAS controls, LCD colour multi-function displays (MFDs) in front cockpit, and ability to carry the R-77 missile and other Russian air-to-ground missiles (AGMs) such as the Kh-31 anti-radiation missile (ARM). It also reportedly had a new and more powerful computer, and digital data links. The aircraft was called Prospective Air Complex for Long-Range Interception. The Zaslon phased-array PESA radar would allow firing long-range air-to-air missiles. Its maximum range against fighter-sized targets was claimed as 200 km. The radar could track up to 10 targets and simultaneously attack four of them with its Vympel R-33 missiles, they said. But eventually the radar would track 24 airborne targets at one time, and attack six simultaneously, they said. Actual development status of radar at that time was not known to us. An upgraded, larger Zaslon-M radar, would later have detection range of around 400 kilometres for AWACS class targets.

There was an infrared search and track (IRST) system in a retractable under nose fairing. Its tracking range was 56 kilometres. The eventual variants were to have various air-to-ground missiles integrated, that included six anti-radiation missiles, or anti-shipping missiles or six precision TV/Laser bombs like KAB-1500. Maximum external load mass was 9,000 kilograms. The MiG-31’s main armament was four R-33 air-to-air missiles. Fuselage could reportedly carry four R-33 or six R-37 missiles. Four underwing pylons could carry combinations of drop tanks and weapons. MiG-31BM could also carry the Kh-47M2 nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missile with a claimed range of more than 2,000 km, and a Mach 10 speed.

The MiG-31 was equipped with digital secure data-links. Details were not told, but they mentioned that the aircraft radar picture could be transferred to Indian Su-30s and MiG-29s. Also the ground radar picture could be received by the MiG-31 and transferred electronically to other aircraft. Thus allowing radar-silent attacks. There was a choice to slew missiles and fire based on inputs from other aircraft through the data-link. The MiG-31 had radar ECMs. Details were not discussed. The onboard navigation and attack system had two inertial systems supported by digital computer.

A detailed briefing on the aircraft was carried out first by Russian designers, and then was the pre-flight briefing by the pilot. Designers told us that though evolved from the MiG-25, there were significant changes. The aircraft fuselage was longer to accommodate the radar operator’s cockpit and there were some other new design features. The wings and airframe of the MiG-31 were stronger than those of the MiG-25. The advanced radar, with look-up and look-down/shoot-down capability and multi target tracking and engagement was a significant improvement. The aircraft had advanced sensors and weapons. Radar they said was much better and worked well even during active radar jamming. They highlighted cooperative work, between a formation of four MiG-31 interceptors, using data-links, which could dominate a large front and airspace across a total length of up to 900 kilometres. The radar had maximum detection range of 200 kilometres. They claimed that the aircraft radar and weapons combination could intercept cruise missiles flying at low altitude, and also the launch aircraft. Similarly it could take on UAVs and helicopters. The automatic tracking range of the radar was 120 kilometres. The aircraft could act as air defence escorts to a long range strategic bombers. The MiG-31 was not designed for close combat or high-g turning.

They also mentioned that the Russian Air Force was already flying the MiG-31, and a few hundreds had been produced by the Sokol plant. The Kazakhstan Air Force had also retained some numbers after Soviet dissolution. They took pride in mentioning that the MiG-31 was among the fastest combat jets in the world. The aircraft had years of service ahead. Cash-strapped Russia was very keen for the IAF to buy the MiG 31.

What were your first impressions?

The blue and white painted huge aircraft with tail number 903 looked most impressive and overbearing as one walked towards it. To start with, the MiG-31 is big. You might say huge. This was the then under development MiG-31BM (air defence) variant. I had read up about the MiG-31. I had earlier seen the MiG-25 in India, though I had not flown it. This one was freshly painted aircraft and much better looking. This was the aircraft which was to be used for display during air shows. As one walks around the aircraft for external checks, one gets to see the huge nose cone that housed the RP-31 N007 ‘backstop’ (Russian: Zaslon) radar. Air intakes were side-mounted ramps. Looking into the huge intake was like looking into a tunnel, and one could see the first stage of the huge engine. With a high shoulder-mounted wing, one could comfortably walk under the aircraft. The undercarriage was peculiar. There were two main wheels in each side and these were in Tandem but not aligned with each other. We were told that the undercarriage had been strengthened to take greater weight, also the fuselage was clearly longer. One recalled that the MiG-25 had only one main wheel each side. Russians also demonstrated the peculiar way the wheels retracted into the fuselage. The wheel trolley did a full forward rotation before entering the wheel bay. The tail side was somewhat similar to MiG-25, though longer a little but difficult to make out.

On entering the cockpit, I was briefed by the pilot, Alexander Georgiyevich Konovalov. We were not allowed photography in the cockpit. The front cockpit was still like the other Russian cockpits with green colour and standard old instrumentation. There were two MFDs which had been introduced in the front cockpit. It looked like a cut and fit task as is the case in developmental aircraft cockpits. The rear cockpit had the old round CRT radar scope. The front cockpit had a standard Russian control column with autopilot and weapon controls. The rear seat had a control stick with no control buttons on the stick-head. This rear-stick could also be removed and stowed away for better radar work. Once the canopy was closed the outside view reduced considerable in the rear cockpit. One got a feeling as if one was seated in a submarine. There was a big periscope to see outside. The cockpit seemed more optimised for WSO role and less for flying.”

How does it compare with the MiG-25?

Both the MiG-25 and MiG-31 were designed as interceptors. The MiG-31 was greatly upgraded to house an advanced radar, digital data links and the more powerful engines. The aircraft had to be made longer. The gross weight of MiG-31 had gone up to 41,000 kg (90,390 lb) vis-à-vis the 36,720 kg (80,954 lb) of the MiG-25. The MiG-31 had two Soloviev D-30F6 engines with 93 kN (21,000 lbf) dry thrust each dry, and 152 kN (34,000 lbf) with afterburner, compared to two Tumansky R-15B-300 engines, with 73.5 kN (16,500 lbf) dry thrust, and 100.1 kN (22,500 lbf) with afterburner for MiG-25.

The MiG-31 was clearly an upgraded design, though it would be wrong to call it a totally new design. Strengthened wings allowed a small increase in max G from 4.5 to 5G, and better acceleration and low-level flight. The MiG-25 radar, was primarily optimised for high-flying targets, but the Zaslon radar of the MiG-31 could detect and track low flying aircraft (look-down/shoot-down capability). The same was demonstrated in flight by locking on to a low-flying MiG-21 that had taken off from same airbase. The rear cockpit in the MiG 31 has been optimised for the Weapon System Operator. The WSO was entirely dedicated to radar operations and weapons deployment. The MiG-31 radar was passive electronic scanned array (PESA) whereas the MiG-25 had older variants of vacuum tube or semiconductor radars. While the MiG-25 (generally) carried only air-to-air missiles, the MiG-31 also carried air-to-surface missiles that included up to four Kh-58UShKE anti-radiation missiles or one Kh-47M2 Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missile.

Interview with Indian Air Force Su-30 pilot here

How well did it accelerate?

“The aircraft accelerated quickly, as if someone was pushing from behind with enormous brute force. Having flown the MiG-23MF whose Tumansky R-29 (R-29A) engine (123 kN (27,600 lbf) thrust) give it excellent acceleration, the MiG-31 was similar. During our sortie we climbed up to 15 kilometres, and accelerated to max M 2.7. The transition to supersonic and subsequent cruise was very smooth. We also flew at low-level to see the acceleration, but did not hit max speed or go supersonic, though the aircraft had the ability. The aircraft pushes ahead like a rocket.”

What was take-off and landing like?

Describe your flight

“The sortie was designed to demonstrate the radar interception performance, aircraft acceleration and general handling. The rear cockpit has only two small vision ports on the sides of the canopy. Fighter pilots are more used to having a great external view. I felt a little claustrophobic. But reconciled to it. There were side screens to make the cockpit darker for better viewing of the radar scope. After take-off the pilot kept the afterburner on for a little while to demonstrate a high rate of climb. We climbed initially to 6 km. Konovalov spoke decent English. He allowed me to handle the controls. The aircraft handling was somewhat sluggish, more like a bomber than a fighter. The rear control stick felt more like holding a rod rather than a control column.

Here we did some radar work. He kept instructing me on how to put on the radar and allow it to warm up and settle down. He also told me how to change range scale. The picture was more like the old time CRT displays of the raw blip type. He showed me an airliner at around 185 km. Since the airliner was not under our ATC control, we did further radar work with a MiG-21 that had taken off from the home base. We locked on to the MiG-21 around 85 km. Later the MiG-21 was asked to descend to a lower height of about 1 km. Then we saw the look-down mode. I do not recall at what range we locked on. I think it was certainly around 40 km. We then climbed to 15 km, where he accelerated the aircraft to M2.7. Acceleration was smooth and fairly quick. He allowed me to be on the controls during acceleration. There was no buffet on the aircraft or on control column. Subsequent deceleration was also fast. For quicker deceleration we initiated a turn (3G).

Once subsonic, I carried out a few turns pulling around 4G. Turns appeared sluggish. In any case the aircraft was cleared only for max 5G. Yes the aircraft was easy to handle, but appeared more like a weapon launch platform up in the sky than a fighter. We then descended to low-level. The MiG-25 was known to be difficult to fly at low-levels. The Russians had made some aerodynamic airframe modifications on the MiG-31 for better low altitude handling. We did an acceleration to around 1100 km/h. The acceleration was smooth. I did not notice any buffet or other aerodynamic effects.”

What was best about it?

“The best part of the aircraft were the acceleration and the long-range radar. I had been told that aircraft has some very long-range missiles. Also the aircraft had been used to launch satellites. The aircraft had significant weapon carrying capability. However, many modern smaller fighters can carry similar tonnage.”

What was worst about it?

“I think it is not appropriate to call anything ‘worst’. I would hardly call it a fighter aircraft. It was basically a weapons platform in the air. More like an atmospheric satellite, or an airborne cruise ship. I also thought that the aircraft still required more refinements in its avionics, displays and cockpit instrumentation. The WSO station in an Su-30 MKI or Phantom F-4 had an excellent external view, this did not. Essentially designed as an interceptor, one could not call it a fighter in conventional sense. I understand that subsequently, the rear cockpit also got an MFD, otherwise working on the old CRT type round scope was not good for situational awareness and information display. For a Mirage 2000 pilot like me, it was a little confusing initially.”

“Comparing the MiG-31 with Rafale is like comparing Bruce Lee with a Para Special Forces Commando.”

How comfortable is the cockpit?

“I sat in the front cockpit for a few minutes. It was like any Russian cockpit with its green panels and black instrument dials. Having flown the MiG-21, MiG-23BN and MF, and few sorties on the MiG-29 earlier, the cockpit looked very familiar. Some of the instruments were same, others had to change to cover a different range of flight parameters. Two MFDs had been brought in. One could see the cut and paste done to the old cockpit to introduce them. One could make out that more changes were still in the offing. The cockpit was spacious like all Russian aircraft, catering for the well-built and well-clad Ruskies. The ejection seat and strapping was also familiar. One thing I always liked about the Russian cockpits was that there was no need for pilot to wear leg restraining straps, as they were part of the cockpit and seat arrangement. The layout of the throttle, stick and positioning of switches appeared good as per flight usage requirements. This had obviously evolved over the years in all counties. Having interacted very closely with Russian designers, especially the cockpit specialists, in our upgrade project, one knew that they were very knowledgeable and real masters at their job. The rear cockpit was somewhat suffocating and tight. Holding the control column was like holding a round-headed walking stick. The stick could be removed from the base and stowed away. Instrumentation in the rear was awaiting an upgrade. Later pictures of the rear cockpit (on the internet) indicate that the MFDs had been introduced.”

How loud is it for the crew?

“The cockpit was well sealed. After all, the aircraft was meant to fly at very high altitude and at very high speeds. I flew with the normal Russian inner and outer helmet. Same as used on MiG-21. The noise level was reasonably low. Even at high supersonic speed it was quite comfortable and one could converse with other pilot comfortably.”

Why the IAF did not buy the MiG 31?

“Russians had made many attempts to try convince the Indian Government and IAF to go for this “multirole aircraft”. Their main USP was long-range missiles (carrier killer and anti-satellite) and a multi-role platform. India had good experience of the MiG-25, albeit mostly in the reconnaissance role. The IAF well understood the complexities of maintaining an aircraft of this type. The MiG-25 had been bought for high altitude reconnaissance. By now, India had its own satellite based reconnaissance capability. Also more and more UAVs were being used for ISR work. Notwithstanding the upgrade, the MiG-31 remained an old platform inherently designed for high-altitude, high-speed interception. It could not be compared to a modern multi-role aircraft. The IAF had already made up its mind with the Su-30MKI for which the contract was actually signed while we were in Russia. We were also interacting closely with the Indian Su-30MKI upgrade team in Moscow. India was also not keen to put the IAF more into the Russian basket. India had had a great experience with Mirage 2000, and was also looking at adding more upgraded variants of the Mirage 2000. Also India had done its threat perception study. It had seen how its own neighbourhood was evolving. India had no such threat from Pakistan. Yes, India needed long-range missile and interceptors for China. But the same could be achieved by putting a long-range missile on any other aircraft. Having a large radar with long-range was the main advantage with MiG-31 which was not possible on smaller aircraft. But technologies were evolving and later better radar performance was possible from smaller radars. In any case the Su-30MKI had a large area of real-estate in its nose. Interestingly the MiG-31A has been used to launch commercial satellites and MiG-31S have been used to train astronauts, to conduct research in the upper atmosphere and for space tourism by launching the aerospace rally system rocket-powered suborbital glider.

Dear reader,

This site is in danger due to a lack of funding, if you enjoyed this article and wish to donate you may do it here. Your donations keep this going. Thank you.

Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

“Not many countries had shown interest in the MiG-31. India also not very sure about the MiG-31’s projected radar capability. Even the Chinese had chosen many Su-30 variants instead of the MiG-31 despite greater potential potency. Unlike the MiG-31, the Su-30 variants manoeuvre very well. The Sukhoi design bureau was also much more aggressive in its marketing. Even a MiG-35 from the Mikoyan stable was considered a better bet, but then India already had plans to upgrade the MiG-29. There was no need immediately for IAF at that time to have an AWACS killer missile. The MiG-31’s capability to launch anti-satellite (ASAT) was not of immediate interest to India. India was already building its own surface based ASAT capability. The IAF’s finite budget allocations could not afford too many platforms. Also buying just 10-12 MiG-31s would have added more logistics complexities to the IAF which already had a plethora of types. As per my knowledge, IAF never did a formal evaluation of the aircraft. The MiG-35 which Russians claim can shoot down almost all kind of reconnaissance drones and other platforms like AEW&Cs and the U-2 spyplane, is one of the contenders of the 114 new fighters India is going to evaluate in the near future.”

What are your feelings on Western versus Russian aircraft – do you have a personal preference and if so, why?

“I have flown a fair number of both Western and Russian aircraft. I have nearly 1,000 hours on MiG-21 variants (MiG-21FL, MiG-21M and MF and MiG-2Bis). I was an instructor on the MiG-21. The MiG was my initial year’s aircraft. I was a pioneer of the Mirage 2000 fleet and commanded a Mirage 2000 squadron, and have around 1200 hours on type. I also happened to have ejected from a Mirage 2000 at the ripe age of 59 years – and two months into the rank of Air Marshal, a sort of record of its own kind. I have also flown the MiG-29, Su-30 MKI, Jaguar and the Hunter, among others.”

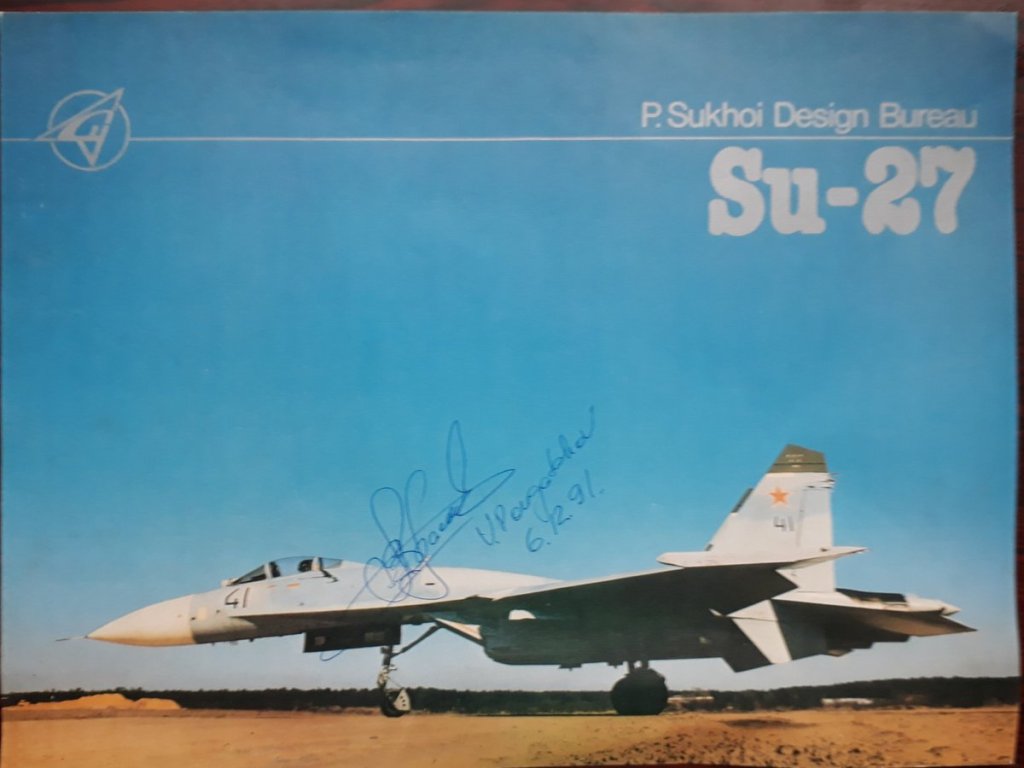

I had earlier done a flight on the Su-27 on 6 December 1991 (my birthday) in Delhi with the famous Russian pilot Viktor Pugachev (of the Cobra manoeuvre fame). I had also flown the Su-30K at Zhukovsky flight test airfield in Moscow with Test Pilot Slava on 13 May 1997. Also flown the under development MiG AT at the same airbase, and the Yak-131D at Sokol. So I have no specific loyalties and can make an independent comment. I had had an occasion to be present at Zhukovsky airfield when the Mikoyan Project 1.44/1.42 aircraft (NATO name: Flatpack) technology demonstrator developed by the Mikoyan design bureau was revealed to the world. Later it had done its maiden flight in February 2000.

Both, the Russian and Western aircraft had their own strengths, weaknesses and idiosyncrasies. Russian aircraft were simpler in design, the cockpits were big, more mechanical than complex electronics, and had high standardisation and commonalty. Switching from one Russian aircraft to other was so much easier. I like the levelling mode of Russian autopilot that brought you to level flight by pressing this button on the control column. This was handy if one got disoriented. I know of someone owes his life to this device. I also liked the simplicity of Russian ejection seats. And they were as foolproof as any Western ones. Russian aircraft mostly had brute power, they were fuel-guzzlers, and some had high specific fuel consumption (SFC), and many passed out smoke through their exhaust. Russian aircraft were cheaper in their base price, but in the long run, their life cycle costs were higher. For example a MiG-29 would overtake a Mirage 2000 in around five years in life cycle costs.

The Western avionics, including electronic warfare systems were more sophisticated. Russians used brute power there too. Russian aircraft required greater stick displacement for any aircraft response, it was much lesser in Western aircraft. This was as per their concept. This had its own dynamics when one changed fleet from Russian to Western aircraft or vice-versa. Pilots had to be cautioned for this. Russian cockpit switches were much larger and easy to operate in the cockpit, the Western were smaller and one had to get used to them while operating with gloves on. The Russian and Western artificial horizon instrument display was quite different. In Russian aircraft the artificial horizon bar turned with the aircraft, thus remained parallel to the aircraft and not to the actual horizon. The aircraft symbol/bar moved twice the degrees to indicate the bank. This worked well when one was head-down. Most pilots really liked this instrument (AGD). In the Head Up Displays of initial Russian aircraft they replicated the same display. This was most confusing because the displayed horizon was different than the real one. We discussed this with the Russian test pilots who had flown some Western aircraft. They also tended to agree with us on this. It took us a great effort and pressure to convince the Russian designers to redo the software to make the MiG-21Bison HUD similar to the Western symbols and logic. Russian designers were not very happy about this. Russian inner helmets were standardised between pilots, tank crew, and even ship or submarine crew. Russian radio navigation system (RSBN) was quite different to the Western TACAN. I found the Russian system very complex and many ways less accurate. The fighter aircraft Air Speed Indicator (ASI) started from 200 km/h, unlike the Western aircraft.

Soviets/Russians remained more than a match for the Western world. They often achieved results with simpler and cheaper means. After all, they were the first to put a man in space and even today are moving ahead with hypersonic weapons. They are being accused by Americans of a cyber-war, so they are still generally demonstrating asymmetrical innovation. There were many more peculiarities of aircraft of both philosophies. Since I have been out of fighter cockpits for some years, I may not remember everything off the top of my head.”

How effective an interceptor do you think it is? How good are the sensors and weapon systems?

“For a successful interceptor, the key attributes are a good radar with long-range detection and tracking, good situational awareness with wider coverage, ability to handle multiple targets, and ECCM features. The MiG-31 radar was indeed powerful and had a good range. I was demonstrated a target at around 185 km range. Also I did see the look-down capability. Beyond that it was difficult for me to comment. In any case the radar and displays would have improved in manifold ways since then. Russian radar and missile combinations have generally done well in some wars including Vietnam and in the Iraq/Iran wars. Though there were other factors for success. Yes, the Americans were able to deceive or jam them with powerful electronic platforms, when they were introduced. Russians believed in brute power in the radar output. Undoubtedly Western avionics are generally better than the Russian ones. Russian missiles are indeed world-class.”

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from Hush-Kit along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here

Tell me something I don’t know about the MiG-31

“Well, Hush-Kit is an alternative aviation magazine of international repute. There is little that you all do not know and I would know. I am a “ageing foggy aviator”. If I was to summarise my flight, I felt I was sitting atop a missile-head in a high-speed interception. The aircraft looked good and was made of razor sharp nickel steel and other metal edges. I liked the white and blue colour scheme. As someone once wrote, I don’t recall who, that comparing the MiG-31 with Rafale is like comparing Bruce Lee with a Para Special Forces commando. Sure Bruce Lee was much faster with his arms & legs but he couldn’t operate 14 different kinds of guns, run 40 km with a 25 kg backpack, navigate through jungles, perform special recon behind enemy lines, kill anyone just with a kitchen knife & rescue hostages. The MiG-31’s cardinal flaw was lack of versatility, and it is too big and clumsy for use in dogfights. That is how the Sukhoi family of Su-27 variants over took from the Mikoyan designs. The MiG-31 is a formidable machine which had its time.”

Describe the aircraft in three words

“High speed brute.”

How many other Indians have flown the aircraft?

“I am not sure if anyone else has ever flown it. I was told that I was the first foreign pilot. As far as I know, no formal flight evaluation was ever done by IAF. Maybe some team went to have a look at the aircraft and had some formal discussions. But I may be wrong on this score. But India was never interested.”

We don’t need no edgy ejection: Interview with man who ejected from a Harrier and played on a Pink Floyd album

| Neal Wharton was the first pilot to eject from a Harrier, a Red Arrow and the only RAF pilot credited for providing jet noise on a Pink Floyd album. Hush-Kit met him to find out more. |

What were your first impressions of the Harrier? “Amazing, amazing and amazing.”

What was your most memorable Harrier mission…what happened? “An 8hr 25min non-stop flight from RAF Wittering (Cambridgeshire) to Downsview Airport (Toronto) in 1972, for the Canadian International Air Tattoo. Some RAF high-ranker got a bit drunk at a Canadian embassy cocktail party and boasted that he would arrange for two Harriers to take part in this event. It resulted in highly complex planning involving two Harriers supported by three Victor tankers from RAF Marham in Norfolk and two from Gander in Canada to see us into the final stage of the flight. At the time, I was display pilot on No 1 (F) Squadron and was given pretty much carte blanche to present a two-ship display off Lake Shore Boulevard in Toronto. I actually got clearance to do a wheels-up hovering manoeuvre during the display over water (Lake Ontario). This was not generally permitted over land (because a loss of power might still lead to a survivable crash landing whereas over water it would be a straightforward ejection option) but it looked great, particularly when followed by an impressive climbing acceleration with the other Harrier coming in from the opposite direction very low and very fast. The display went down very well and was witnessed by a crowd of over 300,000.

Describe the Harrier in three words: “Outstanding British development.”

What were the best and worst things about the Harrier? “Best thing: Versatility and a joy to fly. Worst thing: A tendency to roll uncontrollably and crash if travelling near the ground at low speed with excessive side-slip. Something to do with intake momentum drag!”

What do you remember of your ejection and the flight which led to it? “I remember my ejection experience as clearly now as when it happened just over 50 years ago (October 1970). This was in the early days of the Harrier and we were operating out of RAF Ouston, a disused World War II airfield near Newcastle, practicing for off-base deployments. I took off, leading a pair of aircraft to carry out a live weapons sortie at Tain Range on the Dornoch Firth in Scotland. We were armed with 28lb practice bombs and 30-mm cannon. The sortie was going normally and after completing our mission we left the range to return to Ouston. I radioed the tower as we approached and they cleared us to make an approach for a conventional landing on the runway. As I was leading, I carried out a circuit at around 1000 ft with my wing man a short distance behind me (he had a good view of the whole thing). I turned onto finals and commenced my approach. At this stage my speed would have been around 170 knots and I would have lowered the landing gear, deployed some flap and rotated the nozzles to reduce speed. As I descended through about 700 ft the engine, without warning, suddenly shut down (or ‘flamed out’ as we would have called it). My initial instinct was to check my fuel state (it wouldn’t have helped but that might have been one explanation for the sudden loss of power) at the same time I operated the relight button on the throttle. The aircraft was now descending more rapidly and I made a quick radio call:

‘Mayday, Mayday, I’ve flamed out, I may have to eject’.

I was still desperately trying to relight the engine to no avail and I was now descending very fast (the Harrier has the gliding performance of a brick, as we used to say) and I can remember very clearly that the trees I was going towards were rapidly getting bigger; I was certain I’d left it too late but I grabbed the ejection seat handle and pulled … “

The Harrier has a rocket assisted ejection seat which when activated fires the seat (plus pilot) out of the aircraft with an explosive charge and a split second later the rocket ignites, firing the seat up to a height of 400 feet in less than half a second. Just before the seat leaves the aircraft, a small strip of plastic explosive shatters the cockpit perspex canopy rather than the seat breaking through a solid canopy, which used to happen. I was fortunate in that the aircraft I was flying was almost brand new and was one of only two on the Squadron which had this device.”

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Preorder your copy today here.

The solid well-researched information about aeroplanes is brilliantly combined with an irreverent attitude and real insight into the dangerous romantic world of combat aircraft.

The book will be a stunning object: an essential addition to the library of anyone with even a passing interest in the high-flying world of warplanes, and featuring first-rate photography and a wealth of new world-class illustrations.

Sadly, this site will pause operations if it does not hit its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here and keep this aviation site going. Many thanks

“. . . . my immediate memory on pulling the handle was a huge kick in the backside as the seat was banged out of the aircraft. At the same time I was aware of going up through something like confetti, but which was, in fact, hundreds of pieces of perspex as the canopy exploded. I was now aware of tumbling through the air until suddenly it stopped, as the drogue chute deployed to stabilise the seat before pulling out the main parachute. At this stage I remember looking upwards (which was in fact downwards as I was now inverted) and saw a huge swathe of orange fire as the Harrier struck the ground. (I had been in that aeroplane approximately one second earlier!) I didn’t bother to look up and check whether the parachute had deployed properly (as most people tend to do) because I suddenly realised that I was going to survive, which is a feeling quite difficult to describe. I didn’t have long in the chute but I managed to unclip and lower my personal survival pack (PSP) which contains, among other things, your dinghy – useful if ejecting over water. I hit the ground hard, going backwards and with a wind gusting to 30knots… the sort of conditions which might well have caused a broken leg but not if you were as relaxed as me – I was alive!

I lay on the ground, cautiously examining arms and legs to see if they were still there and was pleased to see that all seemed well and that the chute had collapsed on landing rather than dragging me along the ground in the strong wind. I stood up, unbuckled myself from the chute, and surveyed the scene. I was in a large grassy field with my aircraft blazing furiously a hundred feet or so away, belching out black smoke into the autumn sky. The metal skin round the cockpit was white hot. A lady, the farmer’s wife I discovered later, was cautiously approaching. Her face was ashen and she was very shaken. As she got close to where I was standing she managed to ask, in a quavering voice, ‘Would you like a cup of tea?”

Epilogue:

The engine failure was found to have been due to a worn bearing in the engine driven gear box which powered the main fuel pump. I ejected at about 100ft and the aircraft hit the ground 1.1 seconds later. I received minor neck injuries due to whiplash during the initial part of the ejection sequence but I was flying again two weeks later. I never did get that cup of tea but I did sink quite a few beers with the guys when I got back from the hospital!”

What was your collaboration with Pink Floyd? “Yes, that was me on their album ‘The Final Cut’. It referred to some sound effects that I helped with, using a Hawk and a very low pass at 480 kts!”

Special thanks to Phil Rowles & Martin Baker

Eurofighter Typhoon versus Dassault Rafale video: Part 1

Top 14 Flying Machine Restaurants

Flying and dining, will our relationship to these things ever be fully restored? While we’re waiting for the pandemic to abate, let’s whet our appetites by fondly recalling some of the finest gourmet flying machines in the world. Remember your table manners and pack the Pepto Bismol as we chart, and order, a course for the heights of aero-culinary culture. Some of these places are long gone. A couple of them are truly happy instances of aeronautical conservation, even if they are going to be off limits for a bit longer. For others, well, pass the salt. As with everything else in this life, all is temporary, kids. Stephen Caulfield is out to lunch.

- The Airplane Cafe, Los Angeles, California, USA

Considering some of the monstrosities produced in the first decades of aviation this plywood box could easily be mistaken for an actual aircraft in 1927. Best feature is the light bulb poking out of each cylinder of that radial engine. Cute for sure and with an aspirational gap between the ground and the ‘fuselage’ representing flight. Sadly, even the exact location of The Airplane Cafe is no longer remembered.

Cockpit access: no.

First date prospects: likelihood of success estimated to be high.

- Zep Diner, Los Angeles, California, USA

A brick-and-mortar tribute to the airships of the 1920s and 1930s. How gracefully the Zep Diner glides onto this top list. Picture yourself in Howard Hughes’ Italian loafers walking up those front steps in a natty double-breasted suit. An adoring Hollywood star or starlet on your arm. You both might have ordered well-done Hinden Burgers from the menu. Rather aptly destroyed in a gas main explosion in 1999, the Zep Diner is sorely missed by three generations of Angelenos. Her old corner at Figueroa Blvd and West Florence Ave today hosts only the usual drive-up dreck North Americans have endured for the last hundred years.

Cockpit access: not applicable.

First date prospects: fantastically high likelihood of success associated with the Zep in newspaper accounts and contemporary diaries.

Attention span too short for reading? Subscribe to our YouTube channel here.

- Space Shuttle Cafe, New York City, New York, USA

Aviation history is social and cultural history as well. Can this mash-up of a city bus and a Douglas DC-3 be a depressing metaphor for the decline of a once serious nation and its global hegemony? Is it up for sale online every couple of years? Yes, both.

Cockpit access: driver only.

First date prospects: looks shaky, all depends.

- Douglas DC-3, Taupo, New Zealand

Before 1945 it was a quirky world of independent, owner-operated aero-dining establishments. While rich in character and diversity that world was eventually replaced by a handful of all-powerful chains. This ex-Australian Airways DC-3 bridges both worlds. Some day this airframe will be a five star opportunity for restoration and museum display. One day we will even see it flying again. We feel that in our bones. And in our lower intestines.

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: low-to-moderate likelihood of success expected.

- Flying Saucer Restaurant, Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada

Eye-catching roadside novelty buildings were features of the great heyday of North American consumerism and automobile tourist culture. Aviation and later space travel themes abounded in built structures from the 1930s into the 1970s. The Unidentified Flying Object also entered the popular culture and architecture starting with the Foo Fighters of the 1940s and the flying saucers of the 1950s. A few tired survivors of that era still dot the continent’s biways, stubbornly holding onto the better times. Those were romantic and prosperous days built on hard work, cigarettes, depression, cheap gas and coronary-artery disease. Oh Canada, if only they could have lasted forever.

Cockpit access: not applicable.

First date prospects: very good (especially by local standards).

- DC-6 Diner, Douglas DC-6, Coventry Airport, UK

A handsome vintage airliner from less viral times. A time of optimism and rapid economic growth. A great place for a Lysander Chicken Pot Pie a generation later. This conversion is apparently part of a minor pre-lockdown boom in aeroplane restaurants in the UK. It serves up a brace of meaty dishes that are, wait for it, named after aeroplanes. The UK’s beef-loving geeks and spotters also have a destination now in Lancashire. Post Covid-19 this trend will hopefully grow and grow. Imagine brunching with your love interest in the back of a retired Antonov An-225 Mriya next Valentine’s Day without a mask in sight.

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: moderate-to-high expectations of success.

- Lockheed L-1049G Super Constellation, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Aeroplane bars and restaurants are often accessories to hotels. So it was at Toronto’s Regal Constellation, briefly the largest convention and hotel site in Canada’s business capital. The Globe and Mail looked back in 2011 and said that it ”…was once the hippest hotel in town, with the city’s coolest cats sipping martinis on giant red leather couches while conventioneers from across North America rubbed shoulders in its Arabian Nights-themed bar.” Plunking an ex-Trans Canada Airlines Super Constellation down in the parking lot as a cocktail bar was a 1980s attempt to reenergise the hotel’s fading mid-century glory. Ahead of its time perhaps. The full lust for such things would have to wait for the age of Mad Men. Toronto’s blazing commercial real estate market refuses to tolerate anything but high intensity usage of property between the downtown core and the airport. The ageing hotel buildings were demolished. Luckily, the Constellation was restored for static display. It reposes with the dignity befitting such a beautiful machine.

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: universal reports of absolutely massive success.

- The Airplane Restaurant, Boeing KC-97, Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA

How spoiled we were before the lockdown. So many choices. Eating outside the home tempted us daily. In equal measure, familiarity, quality and tastiness brought us out in the first place. The setting and atmosphere inside our favourite establishments kept us coming back. Local foodies and tourists with an enthusiasm for Cold War airplanes loved to sit where the A-1 jet fuel tankage used to be. Advanced reservations and big lineups were a small price to pay to see this rare 1950s bird based on the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. No smoking within 500 feet, please.

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: moderately successful on most days after 11:00 am.

- LaTante DC 10 Restaurant, McDonnell-Douglas DC-10, Airport City, Accra, Ghana

A happy retirement for one example of a good design that never escaped notoriety for a series of crashes early its career. Indeed, a joyfulness surrounds this conversion of a wide-bodied, trimotor airliner from the early 1970s.

Regional dishes pique one’s curiosity about this cheerful-looking establishment. Would we rather pass the time here or in any post-9/11 airport terminal anywhere on the face of the Earth? Yes, and we’ll have the fish.

Cockpit access: yes (with virtual reality feature!).

First date prospects: enormously high.

Here’s a new thing! An exclusive Hush-Kit newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. Hot aviation gossip, opinion, warplane technology updates, madcap history and other insights from the world of aviation by @Hush_Kit Sign up here:

- Lily Airways, Boeing 737, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China

Airplane-to-restaurant conversions can be interpreted as artefacts of peak economic power. No less than three airliner conversions from the high-growth cities of Asia have made it to this list. The Optics Valley New Technology Development Zone in Wuhan checks in with this fine-dining showpiece. Your table is reached by an airport-style loading bridge connecting to a large commercial development done up in the style of a small European capital city in the nineteenth century. Avoid the bat sushi buffet.*

*Editor: you’re doing that joke, seriously?

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: data is controversial but expectations cautiously positive.

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Preorder your copy today here.

The solid well-researched information about aeroplanes is brilliantly combined with an irreverent attitude and real insight into the dangerous romantic world of combat aircraft.

The book will be a stunning object: an essential addition to the library of anyone with even a passing interest in the high-flying world of warplanes, and featuring first-rate photography and a wealth of new world-class illustrations.

Sadly, this site will pause operations if it does not hit its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here and keep this aviation site going. Many thanks

- Boeing 737-400, Keramas Aero Park, Malaysia

The 737 remains one of the most successful aircraft of all time. It was the DC-3 of its day and so restaurant conversion is a natural second career for them. The 737 is small enough not to be excessive and they are common in the airliner aftermarket. Tuck in to your Nasi Lemak like it was 1970 all over again!

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: moderate-to-good levels of success expected.

- Runway 1. Airbus A310, Rohin Adventure Island, Delhi, India

Fasten your eat belt, people. Shahi paneer, aloo ghobi, palak paneer with pilau rice and coriander naan: that is what we would stuff our faces with if we went here. Then we’d stroll out on that port wing deck with a water view for a drink or six. Wide-bodied airliners offer serious opportunities for restaurant conversion. They have proper entrys and exit points, reasonable head room and extra compartments for modern HVAC and safety equipment, washrooms and so forth. Pass the samosas.

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: always strong.

- Grill-Avia, Sud-Ouest SO-30 Bretagne, Amberieu-en-Bugey, France

Some things shouldn’t need explaining. This twin Bretagne could have probably flown if it hadn’t been destroyed by a blaze that began in the starboard grease trap during this one totally crazy New Year’s Eve party. What a way to ring in 1989!

Cockpit access: two for the price of one.

First date prospects: good-to-outstanding level of success guaranteed.

- Lockheed Super Constellation, TWA Hotel, JFK Airport, New York, USA

Has there ever been a better time to live in the past? Now your retro escape to the near past when the future was still something to welcome can be taken to boutique levels. Right in the grounds of the original mid-century Aerotropolis itself. Constellation conversions seem to have made sense over the years given the size and initial supply of them at low cost when jetliners were taking over. Few other objects say ‘cool’ and mean it as much today as they did sixty-five years ago quite like a Constellation does. Small wonder this model of airliner makes a double appearance here and has at least nineteen cocktails we know of named after it.

Cockpit access: yes.

First date prospects: honey, it’s never ever gonna get any better than this.

Fleet Air Arm Myth #5 Taranto inspired Pearl Harbor

The Japanese have taken many Western concepts and improved on them. Trains, home electronics, and vending machines for used underwear are just some of the items that spring to mind. [1] Popular opinion in the author’s twitter feed is that this includes raids on harbours by carrier air power. The logical line being drawn that the attack by the Fleet Air Arm on Taranto on 11 November 1940 inspired the 6 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service.

The Royal Navy had been considering how to attack a fleet in harbour for the two decades preceding the Second World War, after the frustrating experience of only having one go at the German High Seas Fleet in the First when they refused to come out for a second round after the Battle of Jutland. They’d also carried out the first carrier-based air raid on 19 July 1918 on the airship base at Tondern. [2] Putting the two ideas together was in fact on the to-do list when the armistice got in the way.

The Taranto raid was no spur of the moment thing, planning for an attack had started in 1935 onboard HMS Glorious during the Abyssinian Crisis and was updated and rehearsed in Malta during the Munich Crisis of 1938. RN intelligence had established the depth of the nets surrounding the Italian battleships and it was determined that they’d allow a torpedo to pass underneath. The trick would be stopping them hitting the 40’ deep seabed, achieved by attaching a wire to the front. They wouldn’t hit the hull but handily the British had developed the Duplex torpedo pistol that was set off by the magnetic influence of the ship passing overhead. Or not, which is helpful if you’re HMS Sheffield being attacked by Swordfish that have mistaken you for Bismarck. In the week preceding the raid multiple convoys were routed across the Mediterranean while the Fulmars from Ark Royal and Illustrious ensured no Italian aircraft observed the latter’s task group approaching Taranto. [3] Consequently, the raid came as a complete surprise to the Italians who’d thought they knew where all the RN’s ships were, and that they’d see any naval attack coming. Despite this contrary to stereotypes of Italian martial prowess their anti-aircraft guns were manned and managed to down two of the 21 attackers, as close as you can get to the 10% losses predicted in 1938. In exchange the RN had put 3 battleships on the harbour bottom, although as it was fairly shallow two were back in service within a year, the third still being worked on when Italy surrendered in 1943. The fleet was also moved to Naples to make any further attacks more challenging. Although Taranto briefly altered the balance of power in the Mediterranean and gave the RN more freedom of manoeuvre it would still be contested until 1943, being the biggest navy in the world only gets you so far when you’re also the busiest.

Pearl Harbor clearly had a lot of similarities, a hidden approach to ensure the attack was a surprise, torpedoes used in waters previously thought to be too shallow, [4] and most of the sunk ships re-entering the war. Another similarity was the gestation period of the idea. War games at the Japanese Navy War College had modelled a carrier strike on Pearl Harbor in 1927, with a lecture on the subject by one Captain Yamamoto the next year. Fast forward to April 1940 and now Admiral Yamamoto was discussing a raid on Pearl Harbor with the Chief of Staff of the Combined Fleet. Which unless Yamamoto also had access to a time machine means it was impossible for him to have been inspired by Taranto as it hadn’t happened yet.

It is true Japanese naval officers had visited Italy in June of 1941 and one of the 83 topics they discussed with the Regina Marina was the raid on Taranto. [5] However, as the First Air Fleet under Captain Genda started detailed planning for attacking Pearl Harbor in April of that year even this would have provided limited value.

At best then Taranto may have given the IJN some encouragement that their plan could work, but the plan itself was an entirely Japanese concept. Like Kabuki theatre, or convincing Gaijin you can buy used underwear from a vending machine.

[1] The last isn’t a complete urban myth. Yes, yes I did research this. https://www.techinasia.com/japan-used-panty-vending-machines-fact-fiction

[2] Regrettably by this stage the RAF had been formed so were also involved although the majority of the personnel involved had previously been in the RNAS.

[3] This also disproves myth 5b that the RN didn’t use deck parks until operating with the USN in the Pacific. With Eagle out of action Illustrious had to use one to carry the extra Swordfish along with her usual compliment of aircraft. As did any of her class that carried Sea Hurricanes, because making folding wings is hard.

[4] Unless you were the US observer onboard Illustrious during Taranto who spent a frustrating 13 months trying to convince the USN it was possible. Still at least he got to say ‘I told you so’.

[5] 83 is a precise number but the Italians appear to have kept notes. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2016/december/taranto-pearl-harbor-connection

Bing Chandler is a former Lynx Observer and current Wildcat Air Safety Officer. If you want a Sea Vixen t-shirt he can fix you up.

11 warplanes that stopped killing and started helping

I’ve heard it said that you have to be a little bit mad to take an interest in military aircraft. As much as the more conscientious of us might try to ignore their intended functions, the fact remains that these are machines designed and built to kill people and break stuff.

But we can take solace in the fact that not all is so macabre about the technological wonders over which we salivate. Here are ten warplanes that beat their swords into ploughshares, renouncing their martial lives—even if only fleetingly—for decidedly more humane ones.

11. Lockheed C-130 Hercules ‘The Herky Farmer’

If averting a localised ecological disaster seems a contradictory task for a military aircraft, how about a role that could potentially help to combat the climate crisis?

The C-130 Hercules is best known as a madly successful tactical transport, that also happens to excel at almost every noncombat role its operators can think of; the proverbial jack of all trades, master of…all of them, really. It’s also got some serious teeth, whether as the AC-130 gunship or the MC-130 special operations variants used among other things as the launch platform for the GBU-43/B MOAB (Massive Ordnance Air Blast, a.k.a. Mother of All Bombs).

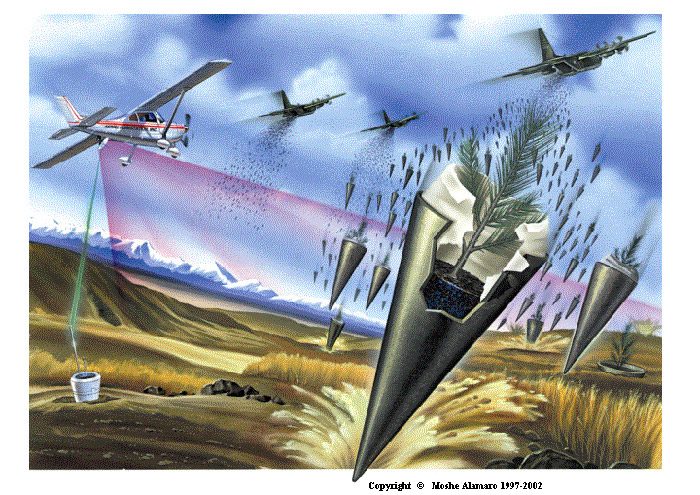

But the heroic Herc has also been used to drop decidedly more life-giving stores. Seed bombing—or, more diplomatically, aerial reforestation—has been around since the 1930s, but came into its own when a former RAF pilot, Jack Walters, came up with an idea to convert equipment used for laying landmines for dropping seed canisters. The concept, which now consists of placing a seed, fertilizer, and insecticide inside a biodegradable capsule that looks a bit like the bastard lovechild of a household plant pot and a howitzer shell, was adopted by Lockheed Martin. New technology like GPS, high-resolution cameras (sometimes attached to remotely piloted airships), and timed ejection devices not unlike the ones used by the likes of RAF Tornado fighter-bombers to crater runways during the Gulf War has made the method extremely efficient and cost-effective. Seed bombing has been used in places like Africa, Haiti, Scotland, and Mexico.

10. McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II ‘Phantom Organ’

The F-4 Phantom II is best known for wreaking devastation from Southeast Asia to the Middle East, for being the tip of NATO’s spear at the height of the Cold War, and for generally being an obnoxiously noisy, smoky, brutish behemoth of a multirole fighter. But, just a few days before Christmas in 1986, one USAF pilot used his Phantom not to take a life but to save one.

The passing of four-month-old Michael McCann in North Dakota was certainly a heart-wrenching tragedy for the poor child’s family, but his death would not be in vain, as his heart was resuscitated and packed onto a Learjet with a team of doctors at Fargo’s Hector International Airport to be flown to San Francisco, where a five-month-old boy, Andrew de la Pena, desperately awaited a transplant. But disaster had seemingly struck when the Learjet’s engines failed to start in the cold weather. Time and options were running out. So, North Dakota’s governor put in a call to the Air National Guard.

Within minutes, an F-4D of the ND ANG’s 178th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, the “Happy Hooligans,” who happened to be based at Hector, was scrambled. Because the F-4 was intended to be pretty much the polar opposite of an air ambulance, its cockpit isn’t climate controlled, so the organ—which had been out of the donor body at least eight hours, an eternity relative to the medical technology of the time—was placed in an ice-filled plastic cooler and strapped into the Phantom’s back seat, then flown by then Lieutenant (now Brigadier General) Bob Becklund the 1,446 miles (2,327 km) from North Dakota to California at just below supersonic speeds. De la Pena, who seems to be living a quite remarkable life, still has a special place in his heart (pun somewhat intended) for Becklund and the Air National Guard.

As for the Phantom, it promptly resumed its decidedly less humanitarian duties, which, in the case of the Happy Hooligans, primarily involved air defense of the North American continent. This instance wasn’t the only occurrence of a fast jet being used to carry an organ transplant; I’m sure I read that the Royal Norwegian Air Force did something similar with an F-16, but I can’t find the article.

9. Polikarpov Po-2 ‘Night witch of the harvest’

One of the ten most widely produced aircraft in history, this seemingly unassuming biplane had always lived a double life. Sometimes known as the U-2 (“U” for uchebnyy, “trainer”), to be confused with neither the American spy plane nor the disappointing Irish rock band, the sturdy and brilliantly uncomplicated Polikarpov’s value extended far beyond training pilots. The type was used for light bombing, reconnaissance, liaison, and propaganda duties, as well as psychological warfare, where Soviet pilots would fly low over German encampments using their mount’s five-cylinder Shvetsov M-11 engine, with its stentorian popping sound, to deprive their enemies of sleep and fray their nerves with simulated bombing runs. The Luftwaffe found engaging the biplanes particularly difficult, as they flew at treetop level and too slow for the German fighters to manoeuvre into position on. The all-female 588th Night Bomber Regiment used the Po-2 to great effect against the German rearguard. It would see service again in the Korean War, where it was used in night raids on UN bases, which the Americans came to call ‘Bedcheck Charlie.’ The Po-2’s wooden construction gave it an (relatively) infinitesimal radar cross section, rendering it almost immune to night fighters, and its slow speed earned it at least one ‘kill’ when an F-94 Starfire stalled and crashed trying to shoot one down.

But this was just one persona. The other, known as Kukuruznik, was, as its nickname (which translates roughly as ‘corn-sprayer’) suggests, a crop duster. The ethics surrounding the Soviet Union’s agricultural programmes and practices are dubious at best—this is the state, after all, that managed to dry up the Aral Sea—but the harvests were in good hands (wings?) for whoever the state decided was worthy of providing for, with variants of the Po-2 able to deliver up to 250 kg of pesticides. The Po-2 was also built under license in Poland and used as an air ambulance.

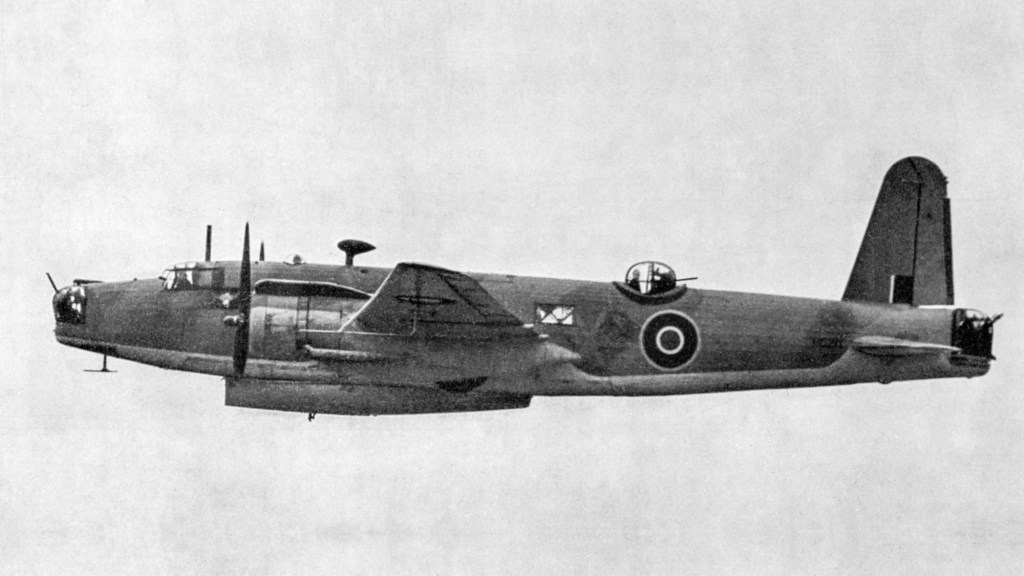

8. Avro Shackleton ‘The contra-rotating Nissen hut’

Aircraft are usually associated more with environmental degradation than environmental protection, but on one rather controversial occasion in 1971, the Avro Shackleton was credited with averting an ecological catastrophe.

The South African Air Force was the sole export customer for the Shackleton maritime patrol bomber, with 35 Squadron acquiring eight MR3 variants beginning in 1957 to replace the Short Sunderland. Fourteen years after its introduction, a SAAF Shack found itself called upon to deploy its armament—not against Soviet submarines, but an oil tanker. On 27 February of that year, the SS Wafra suffered a steam turbine failure while en route to Cape Town, causing the engine room to flood. An attempt was made to tow the stricken vessel into port, but the tow cable snapped, and Wafra ran aground on a reef near Cape Agulhas, rupturing eight of the tanks and spilling at least 26,000 tons of crude oil (some accounts say far more), swamping beaches and polluting a penguin colony.

While efforts were made to mitigate the extent of the spill, the ship itself remained on the reef, still leaking oil. The decision was made to sink the vessel before any more damage could be done. In early March, Wafra was refloated and towed off the reef, where she promptly broke apart. The larger portion was towed 200 miles out to sea (leaking oil all the way), at which time the SAAF was called into action. First on scene were Buccaneer strike bombers of 24 Squadron, which fired AS-30L laser-guided air-to-ground missiles at the hulk, succeeding only in starting a fire. (If only they’d taken note of the British debacle following their similar attempt four years earlier in the disaster of the tanker Torrey Canyon.)

Clearly, a change in tactics was needed. On 12 March, the SAAF deployed its Shackletons, dropping a total of nine depth charges on the tanker, which quickly broke apart in 6,000 feet of water, a depth where the remaining oil would pose no further threat to the coastline.

Like the F-4, the Shackleton went right back to its military duties, but for that moment, it got to play the saviour to human, avian, and marine life alike.

7. Curtiss C-46 Commando ‘Ol’ Dumbo to the rescue’

I was going to try to avoid listing transport aircraft, as cargo haulers don’t (usually) participate directly in the killing, and almost every transport type has been used in some form of humanitarian role such as disaster relief. But the vital work that the C-46—once the poster child for flying the ‘Hump’ in the China-Burma-India Theatre of World War II—continues to perform in the far north makes it worthy of a mention.

Transportation in the northern reaches of North America is a logistical nightmare. Road infrastructure is spartan at best, and frozen ports and rivers preclude seaborne shipments in some places for large portions of the year. Aviation isn’t just a luxury—it’s many communities’ lifeblood. The C-46, together with former war veterans such as the C-47, C-54, and C-118, flies with operators like Buffalo Airways in Canada and Everts Air in Alaska to deliver much needed supplies and especially fuel, providing a year-round link for isolated communities.

6. Bell AH-1 Cobra ‘Snakes on a plain’

It’s no rarity for military helicopters to have second lives in the civilian sector. Types ranging from the Bell Huey (and its myriad variants) to the Boeing Chinook and Mil Mi-8 have been employed in tasks like construction, logging, passenger carrying, search and rescue, policing, and giving television watchers an eagle-eyed view of the latest horrible event in their hometown on the evening news.

You’ll note that none of those aircraft are attack helicopters, which are generally designed with a singular, macabre purpose in mind. But with the right creativity, even these killing machines can be repurposed for the good of humankind. In the early 2000s, the U.S. Forest Service acquired a number of Army-surplus AH-1Fs, ditching the guns and hardpoints for additional cameras and sensors, creating the Firewatch Cobra. While the USFS Firewatch aircraft don’t directly fight fires, a handful of surplus AH-1Ps acquired by the Florida Department of Forestry and renamed Bell 209 Firesnake are equipped to carry water and retardant systems. Instead, the Firewatch Cobra is used to relay information to ground crews and fixed-wing air tankers to facilitate a more accurate and effective attack. Its infrared sensors can detect flames through heavy smoke, and it can transmit high-resolution images of the fire from its low-light cameras to ground teams up to thirty miles away.

5. Rockwell OV-10 Bronco ‘Broncosaurus Flex’

Apropos of aerial firefighting, the Bronco, better known as the slower, uglier, more American Pucará, is essentially the fixed-wing version of the aforementioned Cobra. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection—CAL FIRE—acquired a number of these former counterinsurgency aircraft to replace the O-2 Skymaster to provide airborne command and control, a set of eyes in the sky for the incident commander on the ground. Crewed by a pilot and an air tactical group supervisor, the Bronco provides a manoeuvrable platform with excellent cockpit visibility for observing a fire’s dynamics and directing fixed- and rotary-wing tanker assets.

4. Airco DH.4 ‘A letter from the flaming coffin‘

The end of World War I saw a flood of surplus military aircraft into the civilian market, many of them finding new lives carrying mail. Airmail was one of the earliest large-scale non-military applications of aircraft; after all, in an era long before email and robocalls and social media, the fastest way to get your spam to fools in other parts of the world was to stick it in a stamped envelope and send it on its way. Then, just as today, speed was a priority, and as such, companies such as United Airlines, today one of the largest air carriers in the world, got their start hauling letters and parcels.

Several ex-Army types were employed on mail runs and limited passenger-carrying services, but Geoffrey de Havilland’s light bomber stands out, finding success on mail runs on both sides of the world, with Qantas and the U.S. Post Office making extensive use of the aircraft, the latter modifying it into the DH.4B variant with an enlarged rudder. The DH.4B was used to establish the first transcontinental airmail service in North America, between San Francisco and New York, operating from 1924 until the privatization of airmail in 1927. The DH.4 also saw extensive postwar use in Canada, where it was used for forestry patrol.

3. Avro Lancaster ‘Lanc-danke’

There’s an old Japanese proverb that ends with “the sword that kills is the sword that gives life.” While in its full context that statement refers to something entirely different, taken in isolation, it’s a fitting aphorism for the role of the Lancaster over Berlin: the bomber that once rained death and destruction down on the city would be aiding in the effort to keep its citizens alive just a few short years later.

During the Berlin Airlift of 1948-49, the Allies scrambled to scrounge together as many aircraft as they could to maintain the air bridge into besieged Berlin. While the C-54 Skymaster and C-47 Skytrain are the aircraft everyone thinks of when they hear Berlin Airlift, a number of types were called upon to carry rations to the city’s inhabitants, the Lancaster bomber (together with the Lancastrian, an airliner and transport derived from the Lanc) among them. One can only imagine the thoughts going through the head of any Berliner with a knack for aircraft identification, seeing the aircraft that had been used to raze vast swathes of their city now bringing in the goods to rebuild it.

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Preorder your copy today here.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes is a beautifully designed, highly visual, collection of the best articles from the fascinating world of military aviation, hand-picked from the highly acclaimed Hush-Kit online magazine (and mixed with a heavy punch of new exclusive material)

This site will pause operations if it does not hit its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here and keep this aviation site going. Many thanks

2. Lockheed P-2 Neptune ‘The Truculent Fire Turtle’

Large ex-military aircraft often find retirement jobs fighting wildfires—those air tankers that the Cobra and Bronco we talked about get to guide to their targets. Former naval types such as the PBY Catalina, CS2F Tracker, AF-2S Guardian, and PB4Y Privateer have been particularly attractive for this role. The P2V (later P-2) Neptune had arguably the most successful career of them all, with its 2,000-gallon water/retardant capacity and the power boost from its underwing J34 turbojets that came in handy when operating at low level in mountainous terrain.

The Neptune’s potential as an air tanker was realized in the late 1980s, and it flew with numerous operators including Aero Union, Minden Air, and the aptly named Neptune Aviation. Air tanker P-2s featured a sophisticated (for the time) digital metering system featuring computer-controlled, electro-hydraulically actuated doors for a continuous water or retardant release from 50 to 700 US gallons per second, allowing for a uniform dispersal pattern eliminating gaps or overages.

Alas, aerial firefighting is no walk in the park, and at least nine tankers were destroyed in accidents over the type’s thirty-year firefighting career, with several more experiencing landing gear failures toward the end of its service life. A high-profile crash in 2012 precipitated the end of the Neptune in air tanker service, and the last user, Neptune Aviation, retired theirs in 2017, replacing them with modified BAe 146s.

1. Lockheed P-3 Orion ‘Friggerock ‘n’ Roll’

Not to be outdone by its predecessor, the P-3 Orion continues to perform sterling work nearly sixty years after it entered service. From dubious roots in the troubled L-188 Electra airliner, the Orion has evolved into an aircraft that, in addition to being one of the most successful maritime patrol aircraft in history, has been indispensable in ancillary roles like long range search and rescue, fisheries patrol, and ice monitoring. And that’s just the ones still in military service.

Like the Neptune before it, some Orions were converted into air tankers. But putting the wet stuff on the red stuff isn’t all the P-3 has been up to in its new life. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center operates a P-3B from its Wallops Flight Facility in coastal Virginia as an aerial science laboratory. But perhaps the best-known civvie Orions are the WP-3Ds of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)—the Hurricane Hunters. Together with some USAF WC-130Js, these aircraft and their crews brave some of the most treacherous weather on earth to acquire real-time storm data to save countless lives.

-Sean Kelly is an operations supervisor at Pittsburgh International Airport who spends most of the time he isn’t being paid to do things related to aircraft doing things related to aircraft (and occasionally writing science fiction).

Who was the first supersonic man? Former F-15C pilot takes a dive into supersonic tails of the unexpected

The great test pilot Chuck Yeager, the first supersonic pilot, passed away this week. Former F-15C pilot Paul Woodford takes this opportunity to break some popular sound barrier myths – and take a tail-ward look at supersonic aircraft.

A couple of weeks ago I posted a photo of Jacqueline Cochran to my Facebook page, along with a note explaining that she was the first woman to break the sound barrier when she flew an F-86 Sabre past the Mach in 1953. A friend posted this comment:

You should add “in level flight”. Lots of WWII fighter pilots broke the sound barrier in combat dives, many died because they did not understand why their controls suddenly became useless.

I responded with this:

There’s a certain amount of mythology about WWII-era prop fighters exceeding the speed of sound in dives. Not known to have ever happened. The control problems some pilots reported happened in transonic flight as shock waves built up around the airplane and the elevators lost authority (which is why supersonic aircraft have all-moving horizontal stabilizers today). The F-86 Cochrane flew was a hopped up Canadian built version with a big engine, and in fact she had to dive to hit the Mach … the F-86 couldn’t go supersonic in level flight.”

I want to flesh out my response, mostly by way of rumour control. First of all, let me stress my lack of aeronautical engineering credentials. I’m an English major. There’s a lot I don’t understand about the mechanics of transonic and supersonic flight. What I do know is what I was taught in flight school, and what I experienced in my years flying supersonic trainers and fighters. If I screw up some of the principles and technical language, I hope you’ll forgive me, but I think I’m qualified to address some of the apocryphal tales handed down from generation to generation, and to provide a simplified overview of transonic & supersonic flight and the changes to aircraft flight controls necessary to achieve it.

World War II and prop fighters

At the pinnacle of prop fighter development, aircraft like the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and Supermarine Spitfire could attain transonic speeds in steep dives. The transonic range is generally considered to be between Mach 0.8 and 1.0 (600 to 768 mph at sea level), but since mph numbers go down as you climb into thinner air and lower temperatures they’re not really meaningful, so from now on I’ll only talk Mach numbers. Even if we had at the time understood supersonic flight and knew how to build the thin wings and area-ruled fuselages needed for supersonic flight, compressibility would have still made it impossible to force the big disc of a spinning propeller much beyond Mach 0.9.

In one test flight, a Spitfire managed to hit Mach 0.92 in a 45-degree dive, at which point the propeller and reduction gear left for parts unknown. The test pilot was lucky to survive. Other pilot reports from the time stated that it was extremely difficult to recover from transonic dives. Some pilots described the problem as “control reversal” but that’s not what it was (no one ever had to push forward on the stick to recover from a dive). Control problems resulted from a combination of two factors: one, the physical force required to move the stick aft in a transonic dive was enormous; two, the aircraft’s ailerons and elevators were rendered ineffective by transonic shockwaves forming around the wings and tailplanes. In other words, it was extremely difficult to move the stick in the first place, and when the pilot was able to move it, the ailerons and elevators couldn’t “bite” enough air to control aircraft attitude. The only way to safely recover from a transonic dive was to throttle back to idle and let aerodynamic drag slow the aircraft to a speed at which control effectiveness was regained. Some WWII prop fighters (the P-38 Lightning, for example) actually had speedbrakes that auto-deployed in high speed dives, precisely to keep pilots out of this “coffin corner.”

Early jet & rocket fighters