The aeroplane types a drowning sailor most wants to see

Stephen Caulfield (with support from Jane Morton, Paul E Eden, Sean Kelly and Joe Coles) goes in search of the 15 most noteworthy aeroplanes of oceanic mercy.

15. Curtiss Model F

Lake Michigan is a cold mass of fresh water in the United States. At around two-thirds the size of Scotland it will conjure up dramatic weather at very short notice. It seems fitting that history (sketchily) records the first known air-sea rescue as having taken place there in 1910.

Two Curtiss F-series seaplanes were involved. One of their pilots was compelled to make an emergency landing. The other, knowing imminent harm when he saw it, splashed down and recovered his colleague.

Haphazard rescues of opportunity like this would typify air-sea rescue for most of the next three decades, including the four years of the Great War. This lack of a truly organised search and rescue force was in spite of how dangerous the world was in this tumultuous period. Seaplanes were the obvious choice for saving those in peril on the waves but the land-planes would be there, too.

In an emergency could be mistaken for: Blanchard Brd.1

14. Republic P-47D Thunderbolt

Just when you thought the mighty ‘Jug’ couldn’t be any more amazing, you discover the eight-gun bruiser had a side-gig saving lives. A roaring surplus of horsepower got them to the scene pretty damn quick too, which was of vital importance for those requiring its services. Thrown around by a gloomy North Sea, most likely with hypothermia and injuries, bomber crews wouldn’t last long. Lacking the well organised British rescue system, the USAAF set up their own – allotting older, war-weary ‘razorback’s (earlier variants that lacked the bubble canopy) to an improvised unit called the 5th Emergency Rescue Squadron based at Boxted Airfield near Colchester. Whenever a bomber mission was launched, two P-47 Thunderbolts of the Air Sea Rescue.

Their war weary mounts had the usual pylon loads replaced with smoke floats and flares, but kept their .50 calibre heavy machine-guns just in case they were needed. A canister with an air-drop capable raft was attached to the centreline rack. Some rescue Thunderbolts are recognisable thanks to a rare sliding ‘bubble’ canopy with reduced framing to improve the pilot’s view. The unit saved 938 lives. Somebody buy this fighter a beer. Right now.

In an emergency could be mistaken for: the Mitsubishi A7M Reppu.

13. Dornier Do 24

Look at the long graceful lines on the Do 24’s fuselage. It’s the prettiest plane here. Of course, all rescue planes probably look extremely beautiful to a man who has spent a week in a leaky rubber dinghy with no water, food, sunblock, or much company beyond the circling hammerheads. But the tri-motor Dornier is eye-pleasing to even the less desperate observer, and carried out an enormous number of maritime rescues; around 12,000 souls were saved.

Fascist Spain was supplied with Do 24s in order to boost recovery of Axis personnel from the Mediterranean and kept them for a long time. Air Enthusiast’s January 1972 issue features photos of such a Do 24 landing on Lake Constance at Freidrichshafen the previous August. Still in Spanish SAR markings it had only just been retired, and was returning to the Dornier plant for restoration and museum display.

In an emergency could be mistaken for a Blackburn R.B.2 Sydney.

12. Boeing SB-29

The B-29 has a ghoulish legacy for mass destruction, but it had its more caring moments, too. This SAR adaptation of the Superfortress carried a new type of lifeboat. The EDO Corporation and naval architect Henry Higgins felt that the previous Mark I and II Airborne Lifeboats were good, but could be improved upon. They feared the much greater distances involved with campaigns in Asia would overcome the capacity of the then current British design (created by English boat designer and sailing enthusiast Uffa Fox). The Americans had self-righting vessels and favoured metal over wooden hulls. The resultant machines were the A-1 and A-3, deployed on modified B-17s and B-29s respectively. As the bomber war ramped up in the Pacific, so too did the quality of the equipment and the size of the infrastructure, to save servicemen downed at sea. With an emphasis on organised teamwork, air-sea rescue came of age in World War II. Over-water routes to Japan necessitated a serious array of assets for aircrew recovery. Thousands of personnel at a time might be involved in a post-raid SAR operation. They could be found at the hard-won island bases, in surface ships, submarines, seaplanes, and crewing the SB-29s. Radio communication, radar and electronic navigation guides formed the vital brain of this vast, dangerous operation.

In an emergency could be mistaken for the Bell X-1’s mother ship or a B-50.

- Vickers Warwick ASR

Tool of choice for the Warwick was the Airborne Lifeboat Mks I and II. Designed by the champion yachtsman Uffa Fox, the lifeboats were packed full of useful goodies to aid survival at sea: a Webley & Scott flare signal pistol with lots of rounds and a flashlight with spare filaments for starters; storm suits for seven men, later ten; rations, rope, cigarettes, signal rockets, 28 tins of sugared condensed milk… and a pint of massage oil (presumably for conjugal distractions).

Buoyancy chambers, sails, paddles and a pair of two-stroke inboard engines made the Mk I a substantial craft. A Vincent motorcycle engine powered the slightly larger Mk II. Though one wonders how much small-boat handling skill the average flyer had at the time, thousands of lives were saved by these boats. Lockheed Hudsons were first with the Mk I, but the Warwick replaced them as the primary RAF lifeboat bomber of the war. The Warwick was a larger cousin to the Vickers Wellington. Not quite big enough to go bombing with the four-engine heavies, it was not really needed in roles given to the more numerous Wellington either – it was assigned transport, weather-reconnaissance and SAR work instead.

10. Boeing PB-1G/SB-17

Once in the vicinity of a crash, the crew of a lifeboat bomber like the SB-17 (a converted B-17) had a challenging mission. First they would scan the water for flotsam, smoke, flares, marker dyes or lights. Often the conspicuous glimpse of a yellow dinghy on blue water revealed the presence of survivors.

The rescue aircraft then roared by (on an upwind course) to one side of the ‘target’. It would then use its standard issue bombsight to aim the air-launched lifeboat.

After release, big parachutes slowed the lifeboat’s descent enough to minimise the possibility of damage when it hit the sea. On impact, CO2 cylinders would automatically inflate buoyancy tubes, which also triggered half a dozen rockets. The rockets would trail ropes with floats in multiple directions around the lifeboat to help the downed airmen secure it.

If you don’t find any of this massively exciting, you are dead inside.

.

In an emergency could be mistaken for a Piaggio P.108.

9. Avro Lancaster

The UK’s formal air sea rescue (ASR) capability was just five years old when the Lancaster became its primary airborne asset. Established in February 1941, the Directorate of Air Sea Rescue Services morphed into the Royal Air Force Air Sea Rescue Service by year-end.

While the Supermarine Walrus is forever associated with RAF ASR, the need to reach beyond the seaplane’s limited capabilities saw landplanes locating stricken crew and dropping essential supplies. Fortunate crews thus had a reasonable chance of surviving until a boat or Walrus arrived; sometimes a Catalina of Sunderland flying-boat was available, but these were needed urgently on the front line and could not be relied upon to provide succour.

In May 1943, a Lockheed Hudson deployed an airborne lifeboat operationally for the first time. Now, long-range landplanes could deliver the means to survive until rescue came, and the means to sail towards it. The recalcitrant Vickers Warwick had been intended as the lifeboat carrier and finally came on strength in October 1943, but was never particularly serviceable.

An obviously more suitable aircraft for ASR conversion had entered combat in March 1942. Thereafter, the Avro Lancaster’s brilliance at bomb dropping meant none could be spared for lifeboat dropping. Nonetheless, the type’s capacious bomb bay, range and reliability lent it to ASR, and conversion work began almost as soon as the war in Europe ended.

In February 1946, the RAF’s grateful ASR units began receiving the Lancaster ASR Mk III and discarding their Warwicks. The mid-upper gun turret of the modified ‘Lancs’ was removed, plus they had provision for a lifeboat, and observation windows installed in the rear fuselage.

With a change in military aircraft designations, the ASR Mk III became the ASR Mk 3. Under this title, the Lancaster accomplished its first successful lifeboat drop, in May 1947. The aircraft involved belonged to 120 Sqn, today the RAF’s premier Poseidon operator.

Yet the operational landscape was changing. Search and rescue trials with the Sikorsky Hoverfly helicopter had begun in 1946. Meanwhile, the Catalinas and Liberators delivered under wartime Lend Lease were returned to the US, leaving the UK short in maritime patrol provision.

The Lancaster ASR Mk 3 was ideally positioned as a stop gap – a change in designation to MR Mk 3 (MR for maritime reconnaissance) signalling that, from 1950, MR rather than ASR was the type’s primary mission. Later, this broadened to GR (general reconnaissance) before the Lancaster naturally gave way to the Shackleton.

The Lancaster served as a dedicated ASR platform for only four years, but bridged a decisive period in which ASR became SAR. Through the Lancaster, the skills learned in wartime were passed on to a new generation of personnel flying modern maritime aeroplanes, which evolved to support the helicopter as the primary means of rescue.

In an emergency could be mistaken for a Handley-Page Halifax.

Paul E Eden is the author of The Official History of RAF Search & Rescue

8. Beriev Be-12PS ‘Chaika’

Designed just as seaplane development was cresting, the gull-winged Chaika (‘seagull’) amphibian is a remarkable machine that only entered service in the early 1960s. With typically tough Soviet engineering, this powerful turboprop was created for the serious business of maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare. But it was in the role of search-and-rescue that the Be-12 lasted well into the post-Soviet era, saving the unfortunate from death in the world’s coldest bodies of water. Chaikas also grabbed 42 in-class world records in their spare time – several for climb and speed still stand, and may well stand forever. The two Ivchenko Progress engines generate a total of 10,632 horsepower, equivalent to six of the ultimate Rolls-Royce Merlins. Still in service with the Black Sea Fleet sixty years later, the Be-12 is assured a place in a notional Commie Warplane Hall of Fame for Longevity. Whatever else you care to say about the USSR, some of its military-industrial artefacts are simply excellent… generally ugly, but excellent. Beriev is still in the emergency flying-boat business in 2020 with the uniquely jet-powered Beriev Be-200 Altair.

7. Grumman HU-16 Albatross

The design of the Albatross benefitted from the wealth of experience of seaplane operations during the wartime years. Grumman’s expertise in creating extremely robust aircraft that could withstand operations near or in water resulted in a superlative aeroplane, which took its first flight ten days after Yeager went supersonic on 24 October 1947. The doughty Albatross proved extremely survivable, and could safely manage ten-foot waves. It was sent to places that no other aircraft could reach, and in the Vietnam War proved carried out some utterly hair-raising missions American military HU-16s often resorted to RATO bottles in order to return to the air from a churning sea with the extra weight of survivors aboard.

6. ShinMaywa US-2

After Japan’s defeat, the Kawanishi Aircraft Company which had been responsible for Imperial Japan’s finest flying-boats and floatplanes, stopped work on manned suicide missiles and was reborn as Shin Meiwa Industries (later ShinMaywa). They built upon their legacy of superb wartime aircraft with results culminating in one of the most impressive aircraft in the world today. There is nothing like the US-2, it is the best prop-driven flying boat design ever made. This amphibian is a radical update of the 1960s US-1 introducing the best of early 21st century technology. The secret of its remarkable short take-off, which can be as small as 280 metres, is the ‘blown’ control surfaces; compressed air (from an engine developed for the Comanche stealth helicopter) blows down the control surfaces adding thrust – as well as steering the air flow from the main propellers. This dramatically reduces take-off distance and improves controllability. Controllability and flight efficiency is also enhanced by the presence of a modern fly-by-wire system. Seaworthiness needs to be impressive, and it is. Combined with features already mentioned, the well designed hull and spray suppressor (a gutter that re-routes spray) mean the aircraft is happy taking off in waters swelling with three metre waves.

The US-2 is in the same size category as the biggest flying boats of the Second World War, but they have far more power thanks to modern turboprop engines. With 18,000 shift horsepower it has four and half times more grunt than a Short Sunderland.

The unique qualities and general impressiveness of this aircraft aside, the US-2 project is a small programme – almost a boutique effort – capable of completing only two aircraft at a time. This means the cost per aircraft is likely around the £120 million mark. More export orders would help defray that issue but they don’t seem to be appearing in a hurry. Regardless, the sailors and airmen rescued at speed from the merciless Pacific never complain of the aircraft’s price tag.

- Heinkel He 59

Military aircraft developed in interwar Germany were dishonestly presented as civilian or mailplanes. The He 59 of 1930 was such a devious creation. Its true role (as a naval maritime patrol aircraft capable of torpedo bombing, minelaying and reconnaissance) was concealed. The type fought in the Spanish Civil War and at the beginning of World War II.

Painted white with red crosses like a flying hospital ship, this aircraft was deployed unarmed to French bases for the Battle of Britain. The idea was to work below the big summer dogfights, rescuing valuable airmen from the English Channel and North Sea. Shorter range designs hampered the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain. especially as its main fighter, the Messerschmitt Bf 109E, could barely manage a mission of 90 minutes. The Luftwaffe was the first combatant air force of the Second World War to create an air-sea rescue service, the seenotdienst. This formation was initially successful, but it wasn’t long until the Hurricanes and Spitfires came for them with gun buttons dialled to ‘FIRE’ rather than ‘SAFE’.

Controversy erupted in public on both sides over whether or not the Geneva Convention covered the civil-registered Heinkels. Rescue work has a moral as well as a utilitarian dimension, which can be subject to manipulation. The Third Reich’s propaganda machine turned its attention to this matter. Neither Churchill nor the RAF ended up wasting much sympathy on the German floatplanes, pointing out that the He 59s were fair game since they flew in clear and direct support of Luftwaffe aggression. In reality, it was a hard judgement call to make. One He 59 crew proved that even an underpowered biplane can get lucky once in a while by shooting down an attacking Hurricane.

In an emergency could be mistaken for the Gotha UWD.

4. Lockheed HC-130

Any description of an airframe as ‘the finest ever built’ is bound to be met with accusations of hyperbole, but the Lockheed C-130 Hercules has a very strong case for that title. Excelling in most noncombat roles, and even some combat ones, it was inevitable that the Herc would be adapted for search and rescue. Its combination of range—a USAF HC-130H set a turboprop distance record flying 8,372.09 miles (14,052.94 km) from Taiwan to Illinois in 1972—and robust build make it an ideal platform for numerous SAR duties, including C5ISR (command, control, communications, computers, cyber, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance), refuelling of SAR helicopters, and air-dropping supplies to survivors.

The U.S. Coast Guard was the first to order the HC-130, doing so in 1958 as a replacement for the HU-16 Albatross and HC-123 Provider. Since then, the aircraft has proven its mettle repeatedly; a notable example took place in October 1980, when USAF and USCG HC-130s assisted in a joint US-Canadian operation to rescue the 519 passengers and crew of the cruise liner MS Prinsendam after the ship suffered a fire in the engine room off Alaska in the midst of a nearby Arctic typhoon. The Hercs, together with a Canadian Forces CP-107 Argus, coordinated the helicopter assets and acted as long-distance communications platforms. For years, USAF HC-130Ps were fitted with the Fulton surface-to-air recovery system; if you’ve seen Thunderball or The Dark Knight, you’ve got an idea of how this system, developed by the CIA, worked. In addition, HC-130s and their associate HH-60 helicopters from Patrick Air Force Base were on standby for every launch of the Space Shuttle.

And the HC-130 is only getting better. Both the USAF and USCG are acquiring SAR/CSAR variants of the C-130J Super Hercules, offering higher speeds and service ceilings as well as a 40% increase in range. The Air Force’s HC-130J Combat King II can provide aerial refueling for both rotary and tiltrotor aircraft, and can be refueled itself by any of the USAF’s turbofan tankers. The USCG’s Super Hercs feature the Minotaur integrated mission system architecture, offering superior information processing ability and significantly reduced upgrade and maintenance costs.

As a testament to the aircraft’s versatility and overall value, many of the USCG’s retired HC-130Hs, in the process of being replaced by a combination of the HC-130J and HC-27J Spartan, have been transferred to the U.S. Forest Service for use as aerial firefighters.

In an emergency could be mistaken for Shaanxi Y-9.

— Sean Kelly

3. Supermarine Walrus

The Walrus doesn’t look like air is its natural element. It’s an amphibian, but even the wheels look like an afterthought. No, it’s all about water; its star sign is Aquarius.

Is that surprising? It has a bilge pump; it carries an anchor. From its looks, you’d say Reginald Mitchell spent his holidays on the Norfolk Broads and was inspired to graft bi-plane wings and a pusher engine onto a cabin cruiser. It was intended for catapult launch from battleships, so he built it like one. You can loop a Walrus, but first check there’s no seawater in the bilges.

The small bomb load proved enough to sink a U-boat. But just as the Walrus was not quite an airplane, it was not quite a warrior. When the better, faster and meaner came along, it was given over to air-sea rescue. It found its true calling in saving, not killing.

For the half-drowned, who know hypothermia isn’t far off, a Shagbat was a blanket, a thermos of hot tea laced with rum, it was life. And when the weight of ten Americans from a ditched B-17 couldn’t be lifted, the pilot just pointed the bow towards England, and taxied home.

Jane Morton is a coder involved in an East-Anglian start-up technology company, and a sometime snowboard instructor. She likes flying boats and airships, especially British ones

Want to see more stories like this: Follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Preorder your copy today here.

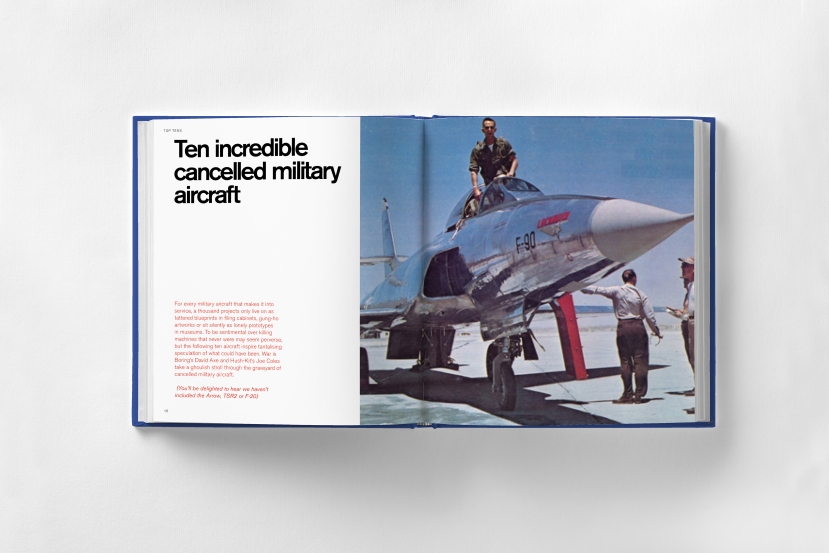

From the cocaine, blood and flying scarves of World War One dogfighting to the dark arts of modern air combat, here is an enthralling ode to these brutally exciting killing machines.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes is a beautifully designed, highly visual, collection of the best articles from the fascinating world of military aviation –hand-picked from the highly acclaimed Hush-kit online magazine (and mixed with a heavy punch of new exclusive material). It is packed with a feast of material, ranging from interviews with fighter pilots (including the English Electric Lightning, stealthy F-35B and Mach 3 MiG-25 ‘Foxbat’), to wicked satire, expert historical analysis, top 10s and all manner of things aeronautical, from the site described as:

“the thinking-man’s Top Gear… but for planes”.

The solid well-researched information about aeroplanes is brilliantly combined with an irreverent attitude and real insight into the dangerous romantic world of combat aircraft.

FEATURING

- Interviews with pilots of the F-14 Tomcat, Mirage, Typhoon, MiG-25, MiG-27, English Electric Lighting, Harrier, F-15, B-52 and many more.

- Engaging Top (and bottom) 10s including: Greatest fighter aircraft of World War II, Worst British aircraft, Worst Soviet aircraft and many more insanely specific ones.

- Expert analysis of weapons, tactics and technology.

- A look into art and culture’s love affair with the aeroplane.

- Bizarre moments in aviation history.

- Fascinating insights into exceptionally obscure warplanes.

The book will be a stunning object: an essential addition to the library of anyone with even a passing interest in the high-flying world of warplanes, and featuring first-rate photography and a wealth of new world-class illustrations.

Sadly, this site will pause operations if it does not hit its funding targets. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here and keep this aviation site going. Many thanks

2. Airbus CC-295 Kingfisher

The CC-295 embodies the diffusion into commonplace service of things that seemed cutting edge just a few years ago. Everything from advanced sensors, digital communications gear and glass cockpits to composite materials, winglets, and scimitar propellers have found their way onto this Spanish design assembled by Airbus in Seville. The Kingfisher is a recent SAR version for the Royal Canadian Air Force. Entering service this autumn, it replaces elderly examples of the C-130 Hercules and DHC-5 Buffalo. With a coastline five times longer than any other country, Canadians are well aware they need a capable search and rescue aircraft. Though late and expensive, the Kingfisher is just the plane they need.

In an emergency could be mistaken for either of the Alenia C-27 Spartan, EADS HC-144 Ocean Sentry or a Transall C-160.

1. Consolidated PBY Catalina/Canso/GST

What a thing a PBY is. This aircraft is perfectly situated between the handsome and the pretty. It’s big, too: as long as two F-16s parked nose to tail, and with the same wingspan as a B-17G. That parasol wing was the first on a production aircraft to contain fuel. Small wonder the PBYs could do 10-, 20- and 30-hour flights across oceans and continents. No small feat in the 1930s and 1940s, but almost routine even for prototype PBYs. Size and range make all the difference in this job, and the PBY was a welcome sight to the lost, time and again. During the war at sea, many would have died without the work of the PBY. Not just as an exterminator of the hated U-boat, but also as the machine that rescued those put into the water by enemy action and wartime accidents.

In an emergency could be mistaken for no other aircraft.

In an emergency could be mistaken for no other aircraft.

What happened to all those Higgins and Fox boats after the war? It sounds like they would make fun pleasure boats. Just curious about the ones with Vincent engines. Vincent built uncompromising motorcycles, sometimes just drifting into just plain weird. Per Wikipedia, the intended lifeboat engine never made it into service.

There’s one, I’m not sure what mark, at the RAF Museum in Hendon.

I’m not sure if it would make much of pleasure craft without as lot of modification, as they’re not particularly large, and it seemed to be mostly made up of watertight compartments for buoyancy and supplies. There didn’t even seem to be something like a cockpit, but possibly that was protected under a hatch.

(A bit more searching shows that they occasionally come up for sale: https://intheboatshed.net/2011/03/25/airborne-lifeboat-for-sale-on-ebay/)

I had known of all the rest but totally had no clue about The Jug being employed in an SAR role, cool!