Cold War aviation art

The bulk of aviation art is concerned with realism, historical accuracy and a sentimental celebration of the machine – and a simple form of national history. The values espoused are at best incurious and at worst jingoistic. But this is not always the case.

World War II cemented the image of aircraft into the public consciousness. Whereas some depictions of wartime aircraft featured a melancholy, a sense of fear or emotional complexity, the exciting, celebratory and cartoonish gained the greatest popularity. By the time of the Cold War’s arrival, contemporary art (where the game was redefining art) and the popularists (interested in easily accessible imagery) had gone two separate ways. They would reconverge at Lichtenstein’s Whaam! of 1961.

Painted and first exhibited in 1961 it is based on an original comic book panel from DC Comics‘ All-American Men of War No. 89 (Feb. 1962). The artist had been drawing inspiration from comic books since the late 1950s. The Tate gallery describes it thus:

The choice of cartoon to represent military action arguably also renders the scene ridiculous and juvenile. Although the intention of the original publication of the comic may have been to show glorious, action-filled images of ‘All-American Men of War’, through Lichtenstein’s quasi-absurdist treatment, the scene is turned into what art critic Alastair Sooke has described as ‘a tongue-in-cheek male daydream of aggression, conquest and ejaculatory release

If we are too look at the work literally, from a plane-spotters perspective, it appears to show a F-82 destroying a F-86, both US types. It is possible that this fratricidal content is intended but seems more like that the images were composites of several cartoon images. The original (right) appears to show a Fury or F-86 Sabre shooting down a MiG-15, two types that did indeed meet in the Korean War. Another cartoon from All-American Men of War (below) No. 90 supports the idea that Whaam is based on two particular frames. It is likely this because the image F-82 is compositionally superior, dominating the left side of the frame and leading viewers in across its wing. The pedantic literalism I have used above, being more concerned with technical or historical accuracy, is very typical of aviation art. Often, this engineering mode of thinking (detail over wider context) has dominated aviation art, though it could, of course, be said that it the application of the category term ”aviation art’ will inevitably lead to categorical styles of thinking.

Gerhard Richter: Series – Aeroplanes (1963-1964)

Many in contemporary art had realised that aircraft as a visual subject was now in the realm of the kitsch, be it patriotic propaganda, ‘boy’s world’ or nostalgia (all places without the ambiguity demanded by contemporary art). If these exciting forms were to be incorporated it could not be about aircraft directly but about looking at how aircraft are portrayed and seen. German artist Gerhard Richter’s Aeroplanes (1963-1964) series depicted aircraft but with a blurriness or background setting which revealed the images were about the imagery of aircraft (often photographs in newspapers in magazines). German artist Gerhard Richter’s Aeroplanes (1963-1964) series included this, ‘Schärzler’ a depiction of a photograph of an EWR VJ 101 in a magazine article (above). The sceptical could wonder whether the artist co-opted a high-brow approach to appease a boyish desire to depict cool military aircraft, but this must be measured against the knowledge that the artist was born in Dresden, a city immolated by aircraft attacks.

Colin Self Leopardskin Nuclear Bomber No. 2 (1963)

The style of Self’s sculpture robs the nuclear bomber of the perceived legitimacy and normalcy of it as a massed produced and modern object. Military aircraft with their cleans and orderly appearance at airfields, have an air of modern respectability, but Self’s use of animal fur associates the bomber with both the instinctive violence of predators and lower technology societies. The nails at the front are brutal, as here is a military aircraft reduced to its core purpose of destruction. The stated purpose of nuclear-armed forces was deterrence for peace, but many suspected a darkly destructive urge at the core, either consciously or unconsciously longing for the end of times. Even without this idea, there was a real danger of nuclear war, leading to mass fear and anxiety.

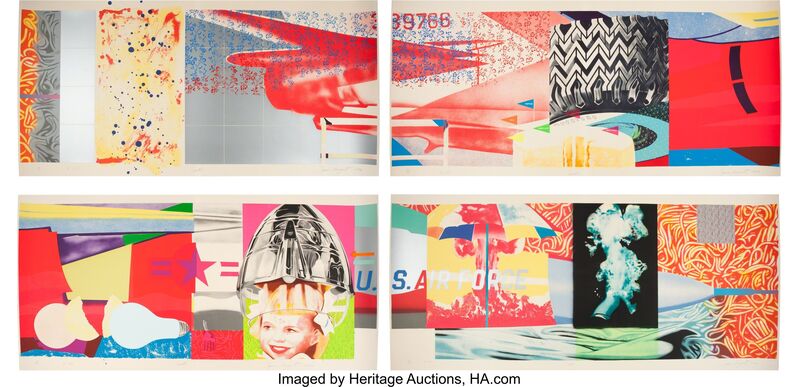

Like many of the pop artists, Rosaenquist was aware that reality was now mediated through the advertiser’s vision. Even the most awful things were to be expressed in the garish colourful simplistic world vision beloved by consumerism.

“Rosenquist was initially inspired to paint the fighter-bomber after seeing an old, abandoned B-36 plane at a Six Flags amusement park in Texas, and in response to media coverage of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam in the early 1960s. Just as he perceived the amusement park as a “false natural environment,” Rosenquist suggested that consumer wealth at that time produced a false sense of security based on the war industry. Civic unrest over the war in Vietnam was beginning to foment in the United States, with small protests on college campuses as early as 1963, and larger-scale demonstrations taking shape in New York, Berkeley, Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., and campuses across America by 1965. This brash, large-scale work was in many ways prescient of the pronounced civil unrest to come, embodying an outsize visual statement that would match the critical voices that were then building against the war. With all the bravura of advertising, Rosenquist created a history painting that crystallized contemporary American life.”

—Text by Sarah C. Bancroft, and adapted from Bancroft, “Modern Issues and Current Events” in James Rosenquist: A Retrospective, eds. Walter Hopps and Sarah Bancroft, exh. cat., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (New York, 2003); and Bancroft, “James Rosenquist: The Intimate Collage of Monumental Painting” in James Rosenquist: Four Decades: 1970-2010, exh. cat., Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac (Paris, 2016). via https://www.jamesrosenquiststudio.com/page/f-111

Protest images

Wolf Vostell’s ‘B 52 Lipstick Bomber’ of 1968 shows a famous image of a B-52 bombing Vietnam with the bombs replaced with lipsticks. The message of the piece appears to be simple: as US atrocities in South East Asia continued to happen, mindless consumerism carries on.

With the ability to carry nuclear weapons, military aircraft held a godly power to scare and destroy, but generally the image of missiles or mushroom clouds were more popular in anti-war or anti-nuclear protest art than aircraft themselves. An exception to this was a frame in Raymond Brigg’s 1982 extremely bleak graphic novel When The Wind Blows which contains a two-page spread showing a force of bombers approaching. Unlike most pieces that would be counted as ‘military aviation art’, it is not masturbatory or gripped by ‘machine-love’. This is not an heroic image, but faceless, dark, vague and intimidating.

Fantasy and science fiction

The cover art of Steam Bird by Hilbert Schenck, loosely based on real-word proposals for nuclear-powered aircraft, demonstrates a science fiction trope of basing futuristic aircraft on actual designs, in this case the British Victor bomber. Another sci-fi hybrid can be seen on the cover of Analog below with a craft clearly based on the SR-71 Blackbird. Aircraft designs were often morphed into spaceships. As ever, the vision of the future was based on the present, to a booming US the future was full of thrusting shiny silver space and aircraft. Much Soviet art of the time offers the same, but with a noticeable lean towards a psychedelic Space Utopianism. To artists in the USSR, in space, psychedelia could be embraced, free from concerns that this was a celebration of decadent western values and avoiding thus avoiding censorship.

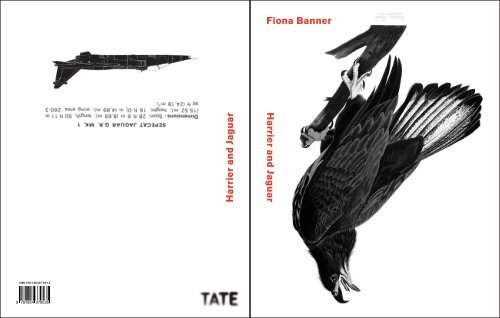

Dead birds

As the initial optimism of the post Cold War Age was quickly burned away by history, Cold War military aircraft returned as dead icons of another time. Fiona Banner’s Tornado Nude, the smelting down of a Tornado into a bell and her gallery-displayed Jaguar and Sea Harrier appear to show artefacts from a dead empire. Banner’s catalogue of every ‘fighter plane’ then in use by the British military draws attention to the cataloguing mindset that so often goes hand-in-hand with an interest in aircraft. Banner has talked about her own mixed feelings on military aircraft, being both horrified and seduced by these remarkable machines. Anselm Keifer’s For Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Voyage au bout de la nuit is a Thunderjet, one full of giant poppies and long since unflyable. The Cold War military aircraft once so vital, are now displayed as rusting archaeologic items.

Superb as always- certainly inducing some chin-rubbing. It’s an insightful piece, but there’s so much more material in this rich vein- let’s have another article on this when you get a chance. Thanks!

Superb blog entry. I *love* this sort of thing. Truly an unique voice you have!