10 Obscure Cancelled French Warplanes of the 1950s

Hugo Mark Michel and Joe Coles previously took you on a tour of France’s strangest aeroplanes, and now, in the happy murk of a remote bar outside Toulouse, and high on fine cheese and wine, they have hatched a fresh conspiracy. They went in search of 10 thrilling – yet somehow scorned – French warplanes from the 1950s that have too long lurked in the shadows. Non, je ne regrette rien? Maybe a few…

10. Breguet Br 960 Vultur (1951) ‘Boule de feu’

France was determined to never again suffer the catastrophe of invasion. So with a blank cheque, the nation embarked on a major post-war shopping spree to radically modernise and reequip its armed forces. One of the big-ticket items was naval aviation, France’s ragtag fleet had three aircraft carriers: a vulnerably obsolete French design, the Béarn, suitable only for transporting aircraft; a British war veteran, Dixmude (A609), also unable to launch and recover aircraft effectively; and the Arromanches which was the sole functional carrier, was built for another age, and unsuitable for modern warfare. It was thus decided to build a new fast and light aircraft carrier, the PA 28 ‘Clemenceau’. But which aircraft should equip this new carrier? The piston-engined aeroplanes available to the French Navy had appeared obsolete with the appearance of the first jet, so several new types were desperately sought. One pressing need was for a maritime attack aircraft, capable of ground attack, anti-ship and anti-submarine warfare missions. This diverse mission set would require an array of armament options including torpedoes, missiles and rockets. The engineers at Bréguet considered the problem and concluded that a fast multi-role long-range carrier aircraft could not be built with a simple existing engine. A combination was required, it would need to use both a turboprop and a turbojet. The turboprop would give it a reasonable patrol speed and superb endurance, while the turbojet would provide a combat dash capability to evade enemy fighters or assist a shorter take-off. The resultant aircraft was the characterful Br.960 ‘Vultur’. This smart two-seater was powered by two British engines type: an Armstrong Siddeley Mamba turboprop to drive the propeller* and a Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet engine, fed by discreet air intakes in the wing roots. Other than its novel propulsion, its configuration was quite conventional, with 16° swept wings and a tricycle landing gear. The side-by-side seat arrangement was adopted, as it was in the later Soviet Tu-91 and earlier US Skyknight.

The first prototype made its maiden flight on 4 August 1951. It demonstrated an impressive endurance of 9 hours, and when the turbojet was fired up it hit a highly respectable speed of 850km/h (528mph). For comparison, the broadly comparable British Wyvern topped out at 383 mph, the US’ Skyshark at 492 mph.

With the second prototype arriving in 1952, landing tests were conducted from February to April 1953. It proved excellent, meeting or beating the expected specifications, especially in terms of maximum speed. However, the cancellation of the PA 28 aircraft carrier project spelled the end for the Vultur, as it was not built to operate from the existing aging carriers. Two other things counted against the promising Vultur. Firstly, the French navy wanted a purely jet fleet for its non-ASW force – for submarine warfare it believed a specialised- rather tha multi-role aircraft, was a better solution. To save their project, the Breguet engineers embarked on a campaign to modify the second prototype, which morphed into the Br.965 ‘Épaulard’, a specialised submarine killer. The aircraft stripped of its pure jet engine, and further refined for the ASW role became the Breguet Br.1050 Alizé, which served from 1957-1962.

* Unlike the similar US Ryan FR Fireball which used a traditional piston-engine

9. SE-2410 ‘Grognard’ ‘A taste for French growler’

The primordial soup of the early jet age spawned some extremely ugly aeroplanes – and the SE.2410 Grognard, known derisively as the ‘Bossu’ (hunchback) was one of them. Of many unusual features, its double-decked jet engine arrangement is the most notable, and was later adopted by the English Electric Lightning (and nothing else).

In 1948, the French Air Force announced that it needed a fast new twin-engine ground attack aircraft. It was a priority, so SNCASE (or Sud-Est) quickly responded with an extremely innovative and surprising concept, the SE-2410. Its two Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet engines, built under licence by Hispano Suiza, were housed one above the other towards the rear of the aircraft, and fed by a dorsal air intake located directly behind the cockpit. This clever arrangement both reduced the forward cross-section area and created room for a neat internal weapons bay. The planned armament was two 30-mm Hispano cannons, and unguided rockets installed in a small folding weapons bay, as well as bombs. The SE-2410 made its maiden flight on 30 April 1950. It was named ‘Grognard’ (literally translating as ‘growler’) the nickname of the Napoleonic soldiers of the Grande Armée. Tests were carried out, revealing that the aircraft was in many ways excellent. After these encouraging first flights, the French Air Force ordered a second prototype, this time equipped with a two-seater cockpit, simply designated SE-2415 Grognard II.

It was in February 1951 that this larger second prototype made its first flight. Unfortunately for the Bossu, it was cancelled in early 1952, in favour of the blandly conventional Southwest SO.4050 Vautour. Before retiring, the two prototypes were used for weapons testing, notably in the support of the first French-produced air-to-ground and air-to-air missiles efforts. It became historically significant as the first French aircraft to fire a French-designed air-to-air missile. After that, the two prototypes were finally abandoned for good.

8. Fouga CM-82 Lutin ‘Rainbow Reaper’ (never flown)

Another ground attack aircraft of the early 1950s was the Fouga CM-821 ‘Lutin’ (leprechaun). This was also a twin-engine aircraft but much lighter than the Grognard. Primarily designed to deploy unguided rockets, the little Lutin had a fuselage and canopy recycled from the Fouga CM.8 R.9 ‘Cyclops’ jet glider. Power was from two Turbomeca Palas engines mounted in nacelles under the wings. The most notable features of the design were the V-tail consisting of two ruddervators with no vertical tail and an almost glider-like high-aspect wing.

A model of the Lutin was displayed at the Paris Air Show in June 1951, which was held for the last year at the Grand Palais in Paris (it was later moved to Le Bourget). This intriguingly petite attack aircraft was never to fly. The CM-82, as well as other related projects varying in ambition, were all axed. This freed enough resources for the design office to devote their energies to developing the extremely successful CM 170 ‘Magister’ jet trainer.

The world would have to wait for the Reaper drone to see what an aircraft of the Lutin’s configuration could do in the attack role.

7. MD-550 ‘Mystère Delta’ (1955) ‘Mystery Jets!’

In February 1953, the French Air Force launched a tender for a new light jet interceptor. They wanted an inexpensive, but all-weather, machine, weighing less than 4 tonnes, and capable of climbing to 18,000 metres in 6 minutes. A speed of no less than Mach 1.3 in level flight was requested, as was the carriage of a 200-kg missile, and a landing speed of less than 180 km/h.

Despite the success of their swept-wing Ouragan and Mystère, MD looked to a new, and largely unproven, technology, the delta wing for the new interceptor. The triangular wing had never been used on an operational fighter. It had only been used on experimental aircraft, such as several French Payens, the US’ XF-92, Swedish Saab 210, and Britain’s nascent FD.2

Order our book here.

Two prototypes were ordered, the 01 then simply called ‘Mystère-Delta’ would be equipped with two British-designed Armstrong-Siddeley Viper turbojet engines built in France under licence and the second one, the MD-560 02, with two indigenous, and far more powerful, Turbomeca Gabizo turbojet engines. The 01, a small aircraft with a massive tail fin and razor-sharp nose, was completed in 1954, and flew on 25 June 1955 with Roland Glavany at the controls. Although considered underpowered, it reached Mach 0.95 on its second flight and during its fourth flight, reached Mach 1.3 in level flight.

While the 02 was still under construction, the 01 underwent numerous improvements across 1956, including the addition of an afterburner, a SEPR-66 rocket engine and even a Martin-Baker ejection seat. The airframe was also refined with a modified vertical stabilizer, air intakes and trailing edges. A new name was also given to the aircraft, a seductively commercial one; because it was said that one could see it, but never reach it, it was given the name ‘Mirage’.

With this raft of improvements, a new test campaign began and the aircraft lived up to expectations with a new top speed of Mach 1.6. But this tiny, not overly powerful, machine’s armament was limited to a single air-to-air missile carried under its belly. The planned Prototype 02 would have had similar limitations, so instead work began on a new, truly impressive, aircraft. This, the MD-550 03, was 30% bigger, and the prototype for what became the hugely successful Mirage III. The MD-550 01, usefully twin-engined, continued flying until 1957 in support of the Mirage IV project.

It is because this prototype flew under the name of Mirage, and that the second prototype was never completed that the designation ‘Mirage III’ was somewhat confusingly adopted for the first operational Mirage.

6. Nord 5000 ‘Harpon’ ‘La fusée sexy’ (never flown)

Responding to the same 1953 call-for-tender as the MD-550 ‘Mystère Delta’, the project proposed by SNCAN was more powerful, far larger, and much faster than its competitors. Nord Aviation ambitiously demanded a Mach 1.6 top speed for their design, rather than the Mach 1.3 specified in the requirement. This sexily futuristic project was known as the Nord 5000 ‘Harpon’. The Nord 5000 was a delta-canard interceptor long foreshadowing the configuration of today’s European fighters. Its design was rather extreme, with wings were fixed very far back in the fuselage while its canard foreplanes almost at the very tip of the nose. finally. It singular appearance was utterly exciting, screaming speed, potency and modernity. A single-engine prototype was to be built fitted with a 1500-kg thrust SEPR rocket engine. A second, far larger twin-engine version would have followed. The story of which engine was intended for this aircraft is a convoluted one. Across the study, between 1952 to 1956 engine technology was evolving so fast that proposed advanced engines rapidly became obsolete. The single-engine variant was initially envisaged with a RR Nene, then an Atar 9, while the twin-engine version was first schemed around the Gabizo then the Orpheus 12. After extensive studies and tests with four models, Nord requested funds to build the first prototype. Unfortunately, for the 5000, the all-conquering Mirage III was already proving perfectly suitable and there was no need for two high-speed interceptors. Nord was not going to give up without a fight however, and pestered the authorities for the budget for at least one prototype in order to explore its advanced design and structure – and to explore the possibility of Mach 2 supercruise. But the authorities stubbornly denied funds and the thrilling 5000 was lost forever.

5. S.N.C.A.S.E. SE-212 ‘Durandal’ (1956) ‘Durandel, Durandel’

According to legend, the sword of the Frankish hero Roland, Durandel, was capable of slicing through giant boulders of stone with a single strike, and was indestructible. It was clearly a cool name for a combat aircraft.

In response to the same 1953 call for tender as the Nord 5000 ‘Harpon’ and the Dassault MD-550, the SNCASE (or Sud Est) design office studied an aircraft similar to the Mystère delta, but far larger. This delta-winged aircraft bore the name of a legendary sword, the Sud-Est SE.212 ‘Durandal’.

Designed to carry an air-to-air missile, but also to perform close support and anti-bomber interception missions, the Durandal was a delta with a single truncated air inlet reminiscent of the North American F-100. Another point of divergence between the MD-550 and Durandal was the choice of engine. At SNCASE, a single French ATAR engine was selected. Initially equipped with a nationally built ATAR 101F turbojet engine, it quickly proved too weedy for Durandal, so the more modern, powerful and reliable Atar 101G was chosen for second prototype. The first SE.212 flew on 20 April 1956 and proved to be a good aircraft overall, but it was the second prototype equipped with the ATAR 101F that really impressed. Capable of flying at Mach 1.57 and reaching an operational altitude of 12,300m, it was spritely but it was another casualty to the new superfighter: It was killed by the appearance of the superior Mach 2-capable Mirage III. The programme was terminated in 1958 following the first orders for the Mirage III. The two SE.212 prototypes ended their careers as flying test beds for SNECMA engines.

The name would later be recycled for an anti-runway weapon, and one of the few French air-launched weapons adopted by the US.

4. SNCASO SO-4060 ‘Super Vautour‘ ‘The Vulture that had to feast on its own corpse’

SNCASO wished to build on the success of the formidable SO.4050 Vautour attack aircraft, and, to stay ahead of the game, create a supersonic successor. From 1953 onwards, a delta wing winged variant was studied, before eventually a swept wing was selected. The new aircraft was to be a two-seater heavy fighter. It wasn’t until 1955, that the French Air Force took a serious interest in the SO.4060 project, and asked the firm to design two versions: an all-weather interceptor capable of Mach 1.3 at 15,000 m and a bomber. A year later the air force’s requirements become even more demanding; this time they asked for a top speed higher than Mach 2. SNCASO’s planned engine, the ATAR 101, was now abandoned as it was not made for flight above Mach 1.3. The new powerplant would be ATAR 9. However, the construction of a prototype had already begun, and the change of engine could not be accommodated in this first example. In 1957 the heavy fighter project was cancelled in favour of the lighter Mirage III, which was already flying and looked extremely promising; the bomber project was also aborted in favour of another Dassault offering, the Mirage IV. The prototype was never finished and the once hopeful project was consigned to the boneyard of history.

3. MD-450 ‘Barougan’ ‘Dirtbike Hurricane’

Whereas many of the aircraft of the Second World War were content with semi-prepared runways in fields or dirt, the new generation of jet aircraft was rather refined in its tastes. These new softies, with their love of long concrete runways meant a single well-placed bomb could potentially paralyze the air defences of an entire region. Thus, in the early 1950s, there was a strong interest in interceptors capable of taking off from unprepared airfields. The best-known result of this research is undoubtedly the SNCASE SE.5000 ‘Baroudeur’, which took off from a rocket cart. But it is much less well known that Dassault were also working on the same problem. Their pleasingly simple solution used the Dassault MD-450 Ouragan, which had been flying since 1949. An Ouragan was specially adapted to take off from anywhere, with a new landing gear that was extensively modified, using twin wheels with low-pressure tyres on the main gear, as well as a braking parachute. The concept was unofficially named ‘Barougan’ (a cross between the Baroudeur and Ouragon). This first version of the all-terrain aircraft took off successfully on 24 February 1954, preceding the conversion of three more Ouragans. They were first tested in France, then directly on the ground in Algeria. Unfortunately for this robust and capable aircraft concept, due to budget cuts, neither the Baroudeur nor the Barougan were to be as the requirement was quietly dropped.

2. Sud-Aviation SA-X-600 (1959) ‘Jumping Jaques Draken’

France was an extremely active competitor in the frantic race to create a vertical take-off and landing fighter aircraft. Prototypes included the bizarre ATAR Volant, the even more bizarre Snecma C-450 ‘Coléoptère’ and the ravishingly sexy Dassault ‘Balzac’.

The Sud Aviation SA-X-600, was a VTOL interceptor study began in 1959. The concept changed a great deal over time, with the only constant being a delta wing and a battery of lift jets. These were RB162 engines, the number of which varied from 4 to 6 across the project. The RB162 was a very light simple jet, specifically designed by Rolls-Royce as a lift jet. The RB162 was employed by significant other VTOL types: the Do 31, Mirage IIIV and VFW VAK-191B.

Thrust for forward flight for the SA-X-600 was provided by an RB153 or RB168. The SA-X-600 was a single-seater, with a teardrop cockpit. Like the Mirage III it had semi-circular main air intakes, with moving conical hubs known as ‘mice’. The most advanced version of the aircraft was an exciting-looking machine, with a double delta wing, like the Saab Draken. No official order came and the aircraft, as promising as it was, was never developed. This was perhaps as the manufacturer had stated a 7-year development time, then considered a very long time.

Sud Aviation was not the only company to spot the potential of a Draken-like configuration for a ‘jump-jet’. On the less chic side of the Channel, in Derby in England, Rolls-Royce’s Geoffrey Light Wilde schemed a similar idea with a design even closer in appearance to the advanced Swedish tactical fighter. Even Hawker in Kingston-on-Thames considered a double-delta VTOL fighter from 1957.

1. Bréguet Br.1120 ‘Sirocco’ ‘Sirocco Siffredi’

A Sirocco is a hot dust-laden wind, blowing from North Africa across the Mediterranean to southern Europe. It can bring the eerie phenomenon of blood rain, in which it appears to rain blood*. It was an appropriate name for a bringer of death from the sky.

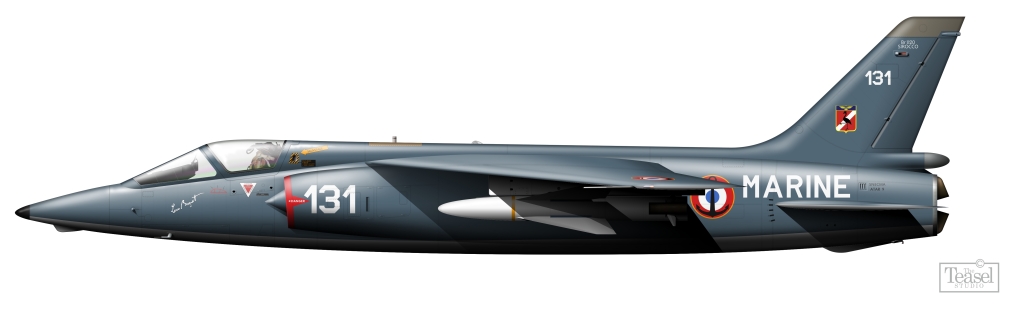

In 1956, the French Navy required a new aircraft. They wanted something multirole, with a top speed of Mach 1.8 (so far so Rafale) capable of operating from the new aircraft carriers ‘Foch’ and ‘Clemenceau’. Dassault and Bréguet each proposed a solution. Dassault offered a navalized Mirage III and Bréguet, the Br.1120 ‘Sirocco’. Essentially an entirely new aircraft, it was a radical evolution of the unfeasibly handsome Br.1001 Taon. Whereas the flea-like Br.1001 had been spritely, the far beefier 1120 was outrageously swift. Powered by an ATAR 9 turbojet it looked to smash through the demanding Mach 1.8 requirement to reach Mach 2.2, making it even faster than the majority of land-based combat fighters (even today).

Cannonless, it was to fully embrace the missile age, armed exclusively with guided air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles. A feasibility study was also underway to equip it with an atomic bomb. A full-scale model of the Sirocco was built, resembling the future Mirage F1. The design had great potential but by the early 1960s, the Navy had grown impatient. Rather than waiting for this superb design to develop, it chose a combination of the foreign, but proven, F-8 Crusaders for the fighter role, and the indigenous Étendard IV for the attack mission. The extremely Sirocco project was now surplus to requirements and cancelled. Though looking at the later F1, its influence may have lived on.

*Caused by algae spores apparently

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. Our site is absolutely free. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here– it doesn’t have to be a large amount, every pound is gratefully received. If you can’t afford to donate anything then don’t worry.

Hush-Kit depends on your donations to keep going, and funding is currently very low. If you love this madness then do support us.

You can also buy our first warplane book here and support our next warplane book here.

It is interesting that a French fighter aircraft combining a jet turbine and a propeller engine was named “Boule de feu.” That is French for ball of fire, and of course the US developed a military plane that used both jet and piston power: the Ryan Fireball. Was the French version intended as a copy?

Hi Jack, that is a jokey title from us indeed based on the Fireball, not an official title.

Oh, thanks for the reply. Your humor was evidently too subtle for me to see it was a joke.

I’ll have to pay closer attention in future to your content, which I find most impressive.