10 Reasons the Vickers Wellesley was amazing (and how it won the War)

The deeply unconventional Vickers Wellesley had a vital and seldom discussed part in the Allies’ victory in World War II. An utterly unorthodox combination of cutting-edge technologies and decidedly old-fashioned thinking, the Wellesley was a world-record-setting aeroplane of beastly good looks.

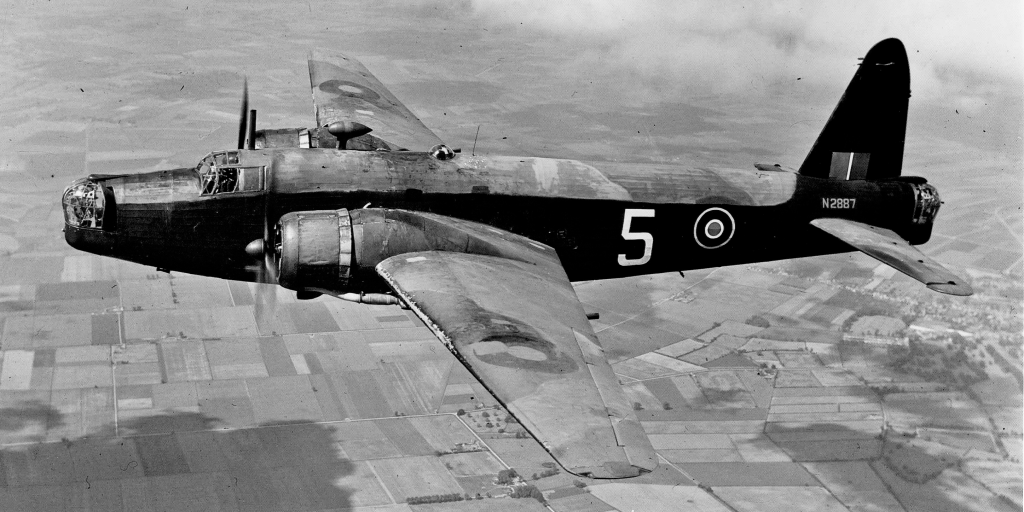

10. Led to the Wellington

The redoubtable Vickers Wellington was the best bomber of Bomber Command in the early years of the War and found gainful employment in every RAF command. Key to its effectiveness was its ‘basket-weave’ geodetic construction that was both light and remarkably strong. The Wellington could not have happened without the maturation of geodetic aircraft construction via the Wellesley.

9. Low weight

The Wellesley’s structure weighed only two-thirds that of the more conventional Vickers Vincent

8. The mystery of Wellesley K7734

Shortly before midnight on the 23rd February 1938 two Vickers Wellesley aircraft of the RAF’s Long Range Development Unit took off from Upper Heyford, Oxfordshire. The aircraft were tasked with a long-distance ‘endurance flight’ around Britain. One of the aircraft never returned. Despite a vast air-sea search effort and news appeals for information, the aircraft and its aircrew were never found. No Mayday was sent, and its last signal was at 7.15 am on Thursday 24th February. The mystery has never been solved definitively, but on 22nd March 1938, a Dunlop tailwheel was found floating off Karmo, 25 miles north of Stavanger in Norway. The type matched that of the Wellesley.

7. Hercules testbed

The Hercules radial engine was a massive success, powering over 25 different aircraft types. The Wellesley Type 289 engine testbed was used to test the Hercules HE15 and was vital to its development.

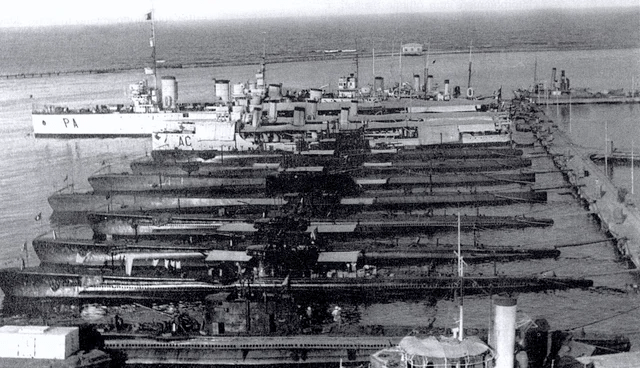

6. Massawa naval base attack

Egypt contains the strategically vital Suez Canal. In the War, the Suez Canal connected Britain with its Empire, which was supplying huge amounts of critical material to the war effort. Without the Suez canal, Britain would be dangerously starved of oil and other vital supplies: it could easily have meant the end for the Empire. When Italy declared war on Britain and France in 1940, it left Egypt extremely vulnerable. The Italians had the Suez canal in their sights and massive numerical superiority in Africa, the Italians also had a powerful local naval force which was composed of nine destroyers, eight submarines as well as a squadron of fast torpedo boats.

Though the British lacked the most advanced warplanes in this region, there was a Wellesley force. No 14 Squadron, along with two other RAF squadrons, was equipped with Wellesleys and based in Sudan. On 11 June nine aircraft from No 14 Squadron mounted an audacious raid against the Italian naval base at Massawa. Massawa was the homeport for the Red Sea Flotilla of the Italian Royal Navy. At sunset 14 Squadron attacked at extremely low level, lower than 500 feet at times, and ignoring the tempting ships, ravaged the port’s fuel stores. The resultant firestorm destroyed an estimated 10,000 tons of fuel.

It is likely that the attempted Italian invasion of Sudan in July was stalled by fuel shortages caused by the raid, buying time for the arrival of later Indian reinforcements that would turn the tide of war. The plucky nine aircraft and their extremely brave crews achieved a great deal in their bold sunset raid on Massawa.

5. It didn’t kill Jeffrey Quill

The 2nd prototype Wellesley flown by test pilot Jeffrey Quill went into a spin and lost control at 10,000 feet on 5 July 1937. Quill pilot baled out and survived. The aircraft landed in the front garden of house in New Malden in South London, photographs taken by a schoolboy on his Box Brownie reveal how remarkably intact the airframe remained, a testament to its extremely tough construction. Quill was the 2nd test pilot to fly the Spitfire and masterminded the development and production test flying of all 52 variants of the Spitfire.

4. Incredible strength

To ensure new aircraft of the time were able to survive the extreme flight loads safely, they were subject to brutal tests that added weights to the airframe equivalent to five times the maximum expected flight loading. Whereas the Vickers Valiant barely survived this test, the prototype Wellesley’s fuselage had successfully endured a factor of 8! The wings had stood up to an astonishing factor of 11. Tests were only halted to prevent the destruction of the test rig. The Wellesley was built like a brick shithouse.

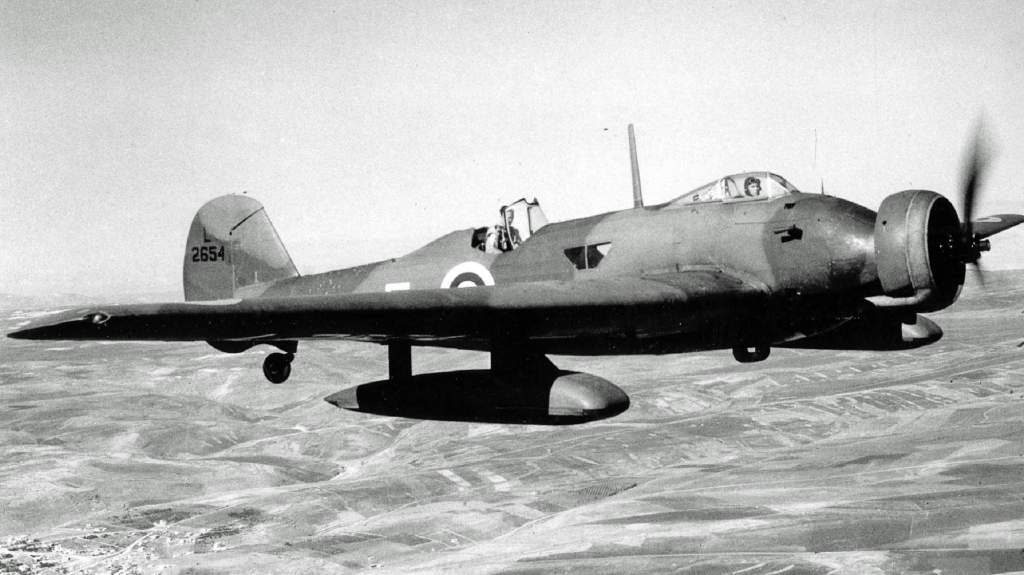

4B. Its looks

The Wellesley looked tough as hell.

3. Geodetic construction

A geodetic construction makes use of a rigid, lightweight, truss-like structure constructed from interlocking struts formed from a spirally crossing basket-weave of load-bearing members. Put simply the basket weave style is stronger and lighter than equivalent conventional structures. This style of construction was first adopted in German airships, then tried in an experimental French aeroplane before reaching maturity in the Wellesley from the design board of Barnes Wallis (famous for his renewable energy generator wrecking ‘bouncing bomb’). Wallis’ famous Wellington bomber could not have been developed without the pioneering design of the Wellesley.

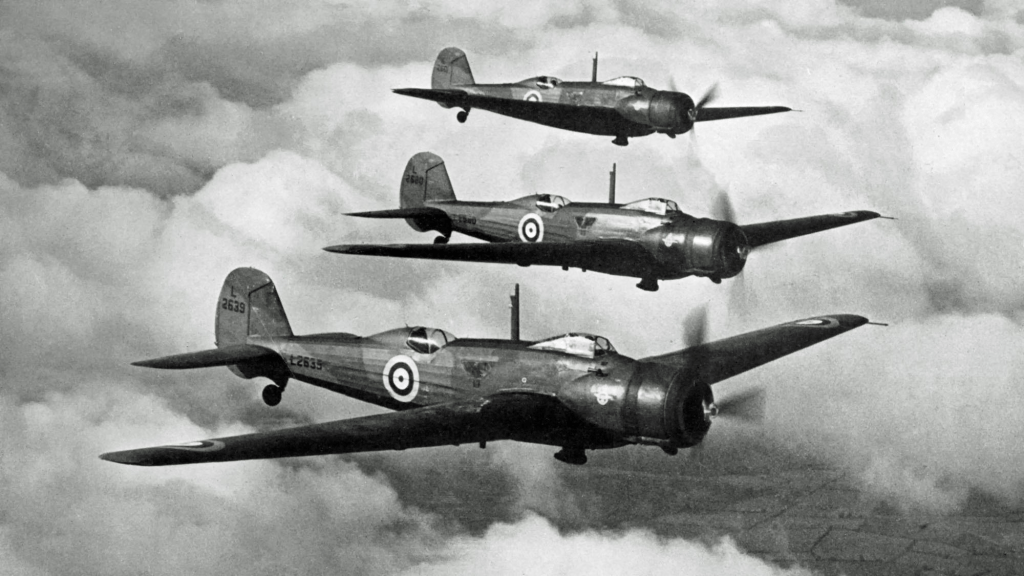

2. Insanely long-range

The long-range capabilities of the Wellesley were astonishing. To demonstrate the startlingly effective work the RAF Long Range Development Unit (LRDU) had carried out on the Wellesley, a widely publicised long-range flight took place in November 1938. The flight was to use three of the five LRDU Wellesleys. These aircraft differed from standard Wellesleys in several ways each designed to maximise range, the most immediately obvious being the replacement of the characterful Townend ring with a slick NACA-style low-drag engine cowling housing a more powerful Pegasus XII engine. Less visible, but as important, was the addition of a slew of cutting-edge technologies that included a constant speed propeller, three-axis autopilot and automatic mixture and engine boost controls. The aircraft was also given plentiful additional extra fuel capacity, bringing the total load to 1,290 gallons. The three aircraft set off on a daunting adventure to fly non-stop from Ismailia, Egypt to Darwin, Australia, a distance of 7,162 miles (11,526 km) on the Fireworks Night 1938. Two days later two of the three aircraft arrived at Darwin (one landed to refuel at Koepang 500 miles short of Darwin, Australia). The result was a world distance record that smashed the previous Soviet-held record by a decisive 1500 kilometres. The record would stand for over seven years when it was beaten by a B-29.

- Recovering the Engima key

It is widely acknowledged that the cracking of Germany’s Enigma code was hugely important to the eventual Allied victory. Key to cracking the code was obtaining a codebook and an Engima machine, both of which were recovered from the German submarine U-559, thanks to a dramatic combined operation which featured an RAF Sunderland and four Royal Navy destroyers, and of pivotal importance – a Wellesley. At 12.34 on 30 October 1942, the 47 Squadron Wellesley spotted the periscope of the invaluable U-559 and attacked with depth charges. The submarine crew eventually surrendered without having time to destroy the coding equipment providing the greatest intelligence windfall of the War.

The Wellesley looked like a Skyraider on steroids.

Yeah, that hi-vis cockpit set-up looks years ahead of its time.

Given the Vickers manufacture, why was it – the Spitfire didn’t

receive a similar – all-around pilot’s view canopy – ’til 1945?