Interview with the man who built a human-powered helicopter (and worked with the legendary Edgley Optica)

Andrew Cranfield started his aviation career in free-fall parachuting and designing (with his brother) his own, highly dodgy, hang glider. Having survived that experience, he set a number of unofficial hang gliding records and became an instructor. He was sponsored by Westland Helicopters Ltd (WHL) through his engineering degree. During his time at WHL, He designed and built a Human Power Helicopter and in his spare time flew early, rather unstable, foot-launched microlights. After being awarded a Fellowship at Cranfield University, he left WHL and his subsequent management career has included working at Optica Aircraft, Lucas Aerospace (on the Osprey V22 project) and running P&M Aviation (The only flexwing designer and manufacturer in the world with UK CAA A1 approval)- an experience that left him seriously out of pocket. He has held senior management positions in other, more profitable, high technology businesses. He currently works as a Non-Executive Director and, amongst other activities, is involved in supporting the Waterbird project (a replica of the UK’s first-ever seaplane) and contributing to an initiative to enhance the skills of UK flexwing microlight pilot.

How on earth do you build a human-powered helicopter and how far did it travel?

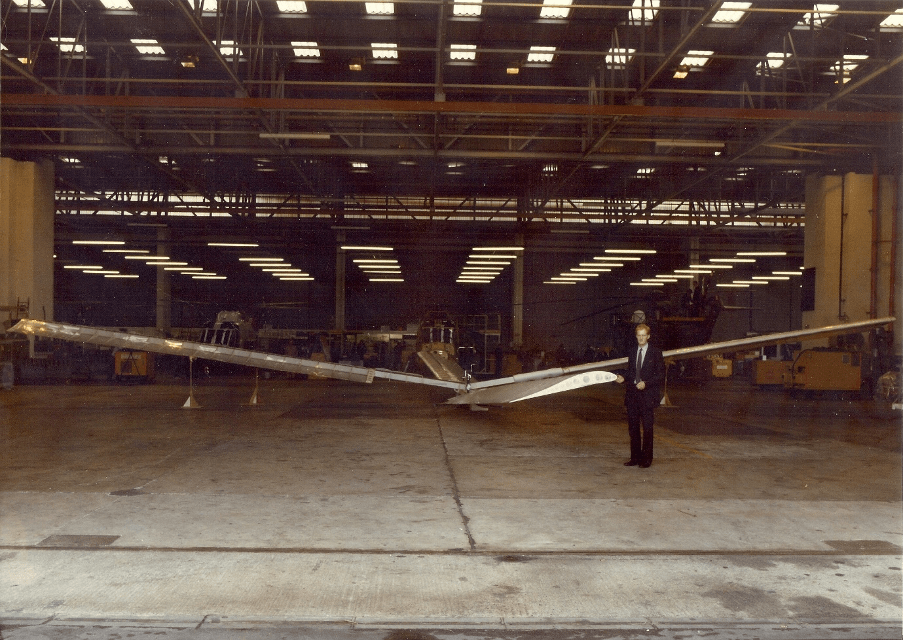

I had a massive interest in Human Powered Aircraft and was, at the time, on the RAeS HPA committee. So I was delighted to have the opportunity, in 1980, to build a HPH when I was a graduate apprentice at Westland Helicopters Ltd (WH). The idea was to win the American Helicopter Society $100,000 prize (a huge sum at the time) for the first HPH to fly for a minute, reach a height of 3m (momentarily) and stay within a 10m x 10m square. The pilot was also not allowed to rotate. I spent 5 years designing and building Vertigo, as I called it. I was very fortunate, in that as it was a company-sponsored project, I had access to highly experienced stress people and other capabilities such as the machine shop and composites dept. We tried to model the aerodynamics on the WHL mainframe, but it crashed as it could not cope with the very low Reynolds numbers! I ended up using a Southampton University programme developed programme specifically for contra-rotating rotors. The design we settled on was a single-seat machine with contra-rotating co-axial two-bladed rotors with the pilot mounted above the rotors. It was primarily made of Carbon Fibre (CF) and lightweight foam with the rotors covered in mylar plastic film. Key dimensions and weight were:-

Rotor Diameter 24.56m

Blade Chord 1.5m

Design Rotor Speed 6 r.p.m

Empty Weight 42.41Kg

The transmission had the pitch and coning built into alloy hubs with CF drive shafts driven by steel bevel gears which, in turn, were powered by a chain-driven pinion gear. The undercarriage comprised of 1m length CF tubes with moulded foam feet.

The key to success was the utilisation of ground effect. Without it, it is not physically possible for a human to fly vertically. As it was, we got it skipping around inside the flight shed at Yeovil but it never actually flew. The person who took it over claimed he got it to fly inside the airship hangers at Cardington but I don’t think anyone ever saw any evidence of that. Bits of Vertigo are now in the Helicopter Museum at Weston-Super-Mare.

It was interesting that some heavyweight and eminent members of the RAeS told me, in no uncertain terms, that I was wasting my time as it was simply not feasible. However, I was very gratified to be vindicated some 28 years later by the Atlas HPH winning the prize. They were kind enough to write and thank me for my pioneering work all those years earlier, which was very kind of them and made me feel it was worth the effort.

Does it fall to earth if you stop pedalling? Yes!

What was special about the Optica, and what are your feelings about it today? I worked at Optica as the Materials Manager after it was brought out from receivership. I remember in some offices, it was like walking into the Marie Celeste, as day books were still lying open with pens resting on them. It was like people had just popped out for lunch – quite surreal. The influence of John Edgley was certainly felt all over the place. Interestingly, l didn’t actually meet John until many years later, through my involvement in Human Powered Aircraft. My feeling was that the failure was not so much in the aircraft concept/viability but more in the business model in trying to sell to govt depts such as the MoD and Police. Where there is no specification, there cannot be a budget. So it takes years for a company to persuade the MoD to come up with a specification. Then it is a few more years before it is included in the equipment budget. Also MoD staff officers rotate every three years, so you are always trying to educate people who then disappear to another posting, so it is an uphill struggle. Any equipment budget is, of course, highly competitive so unless it is an Urgent Operational Requirement (in MoD terms) it is always probably going to be at the bottom of the pile. The original company suffered very bad luck when a low time PPL holding policeman crashed and killed himself in one of the early aircraft through point fixation (banking harder and harder to keep the object in sight at slow speed and low altitude-not something to be recommended) which probably put potential sales back a few years. Sadly, I didn’t get to fly in one, but we had about 10 complete aircraft, if memory serves me correctly, in the hangar but no buyers. I was made redundant on a Friday with one hours’ notice and no money after that. I was told that I didn’t have to work the last hour and could leave there and then. It was also the day that my post-dated cheque was cashed for the microlight I had just brought, with a view of flying to work from a field near my house. When I got home walked through the door, somewhat despondent, my wife asked “Did you have a good day at work?”. However, I did enjoy flying the microlight for a good number of years. A few weeks later, the 10 aircraft were destroyed in what was clearly an arson attack – the wing fuel tank drain taps were left open, and material soaked in petrol carefully laid out as fire paths interconnecting each aircraft. The heat was so intense that all that was left was piles of ash in the shape of an aircraft – even the engines were barely recognisable. Because the roof was timber construction (WW1 hangars) they burnt away without pulling in the walls but enabling a ferocious firestorm to be created. Subsequently, all the ex-employees, including yours truly, were interviewed by the Hampshire police. They, of course, asked me if I did it. When I asked what reason they thought I had, they replied that it might be because I believed that the company would need to re-employ me to rebuild them all! The fact there was no money in the company somehow seemed to escape their notice… However, a few years ago I visited John Edgley to talk about his efforts to resurrect the project, as he had brought back all the drawings and some part built aircraft and bits. However, I am not certain where he has got to with it.

What is the Waterbird project? This is a replica of Britain’s first successful seaplane which operated out of the RN’s first Naval Air Station on Lake Windermere in 1911. My role is purely a helper on the flying side and working as groundcrew, as there are many people involved in the hydrodynamics (the area needing improvement at present) and water operations. Edwardian aircraft like this, are not massively dissimilar to the very first canard two seat microlight aircraft I used to instruct on, so it is very interesting project and I like to think I can add value. The aircraft has done short hops as a landplane but has not yet flown from the water. For the historical background on the aircraft and the establishment of naval aviation, please refer to the Waterbird website.

What is your favourite helicopter type and why?

I have two. The Gazelle because it was the aerial equivalent of the original Golf GTI. I first flew in the type when a trainee flight test engineer at WHL. Once, with a WHL test pilot, the late and great Don Farquharson (who wore a monocle), we had an amazing flight from Yeovil to London. He discovered that I flew hang gliders, we decided to loosen off our straps and we then flew most of the way to Battersea heliport by weight shifting the aircraft as we trundled through a very stable inversion layer. I also did some very low level and fast-flying in Army Air Corp Gazelles, during exercises over Salisbury plain, which was also fantastic. I don’t think you will find a pilot who has a bad word to say about the Gazelle. The Agusta 109, on the other hand, was the Ferrari of the sky. Tremendously fast and with a very smooth ride at high speed (unlike the Lynx). The WHL comms flight example also had a panic button in the middle of the dash. If the pilot lost it (suffered vertigo, for example) you could hit it and the aircraft would stabilise itself and then climb out at 50kts forward speed and something like 500 fpm. I felt, at the time, that was quite an innovative safety feature, although the guys at Hereford thought it was just for wimps.

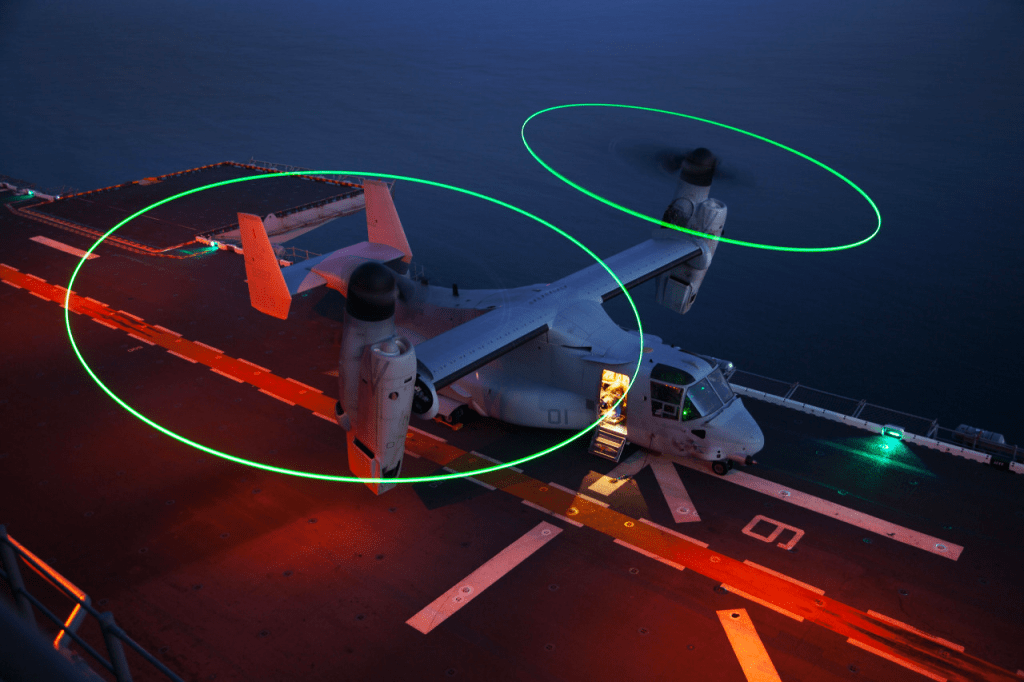

What would you say to those who say the V-22 is not necessary? You have to understand the rationale behind the design. As far as I could make out, the original Statement of Requirement was entirely based around rescuing US hostages from Tehran type missions. The failure of the original rescue seemed to have left a massive scar on the mentality of US Special Operations Command. That failure seemed to dominate the requirements capability all the way through the programme. Only the Americans had sufficient will, money and technology to have developed such a massively complex helicopter successfully, so hats off to them. However, you now have an aircraft which is well suited for certain long-range missions but not so much for other roles, such as traditional SAR work. The key element of this work is being able to hover quite low, while winching people up. Due to the massively high downwash velocities from the extremely highly loaded rotors, this isn’t a really viable operation. That is one example and there are others. But you do have a world-beating aircraft for a relatively small number of tasks that play to its strengths.

What is the biggest myth about helicopters?

That the first generation of commercial helicopters was unreliable and unsafe. This simply wasn’t the case. For example, the Bell 47 (Sioux to the UK Army Air Corps) was, by March 1954, was being operated in forty countries and had logged well over one million hours’ flying time. One American operator, Helicopter Air Service, carried nine million pounds of mail over a total distance of one million miles during three years of operations, using six Bell 47s. Working on three circular routes of between 90 and 100 miles in length, and serving fifty-five suburban communities in the Chicago area, they made 160,000 landings and take-offs without incident, 40,000 of them from a heliport on the roof of the main Chicago post office, 238 feet above ground level! Quite a remarkable achievement.

What should I have asked you – and what is the answer?

Who was responsible for suggesting a prize for the first crossing of the channel by a Human Powered Aircraft? After the Kremer figure of eight prize was won by the Gossamer Condor. We sat around the table at the RAeS and talked about a really stretching, but physically feasible target, for the next competition. I think I said “What about a channel crossing? That should excite everybody. Of course, no one is going to actually achieve it for a very long time”. We all sagely agreed that was a wonderful idea and that indeed it would not happen in the foreseeable future. Within 2 years of Paul MacCready and his team did it with Gossamer Albatross…..

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the site

Andrew and I know each other from our mutual time at Westland. I have half an hour of dual flying in the Optica – a nice little tale that can be found at: http://www.ronandjimsmith.com/books/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Optica-Eye-in-the-Sky.pdf