Top 10 Polish aircraft

Lepszy wróbel w garści niż gołąb na dachu

( A sparrow in the hand is better than a pigeon on the roof ) – Polish proverb

We are battered about the head with generous ladleful’s of the aeronautical accomplishments of Britain and the United States. Those after marginally more specialised histories can readily leave the high street and find plentiful shady backstreet dealers to satisfy the more demanding palates of those wishing to gorge on French, Soviet or even Swedish subjects. But some absolutely fascinating tales from other nations, even in today’s bountifully expansive world of aviation writing, are seldom seen outside of their national languages. The independent nation of Poland is younger than the aeroplane itself, and spent its formative years in bloody wars with Ukraine, the Soviet Union before invasion by Germany and then domination by the Soviet Union. The unique story of its aviation industry, and its beautiful and monstrous flying machines, is ripe for the telling. So what happened?

Popular ideas of Poland’s contribution to aviation history centre on its fighter pilots’ valiant service in the Battle of Britain, and the notion –– disseminated by German and Soviet propaganda –– that pre-war Polish aircraft were hopelessly obsolete. Due to the long lasting efforts of Goebbels and Stalin’s propaganda machines, most of the achievements of the Polish aviation industry in this time remain largely forgotten. As we shall see, several Polish designers were heavily involved in the creation of some extremely famous British aeroplanes.

Before we dig into the history of some brilliant and often overlooked aeroplanes, let us first look at the reasons that the Polish aviation industry was the way it was. Firstly, it’s worth noting that Poland was the only country in Europe to match German developments in glider design in the pre-war period. Whereas Germany was forced to choose that path due to the Versailles Treaty restrictions, Poland was simply poor, having just been resurrected in 1918 after 123 years of slavery under Prussian, Austro-Hungarian and Russian occupation.

Secondly, it has to be remembered that this newly independent nation only had 19 years in which to develop its indigenous technology before World War II started. Thirdly, the birth of the new Poland fuelled an incredible amount of patriotic confidence within the Polish people, and aviation became one of the fields where they felt they could excel.

10. RWD-9 ‘The Messerschmitt-Beater‘

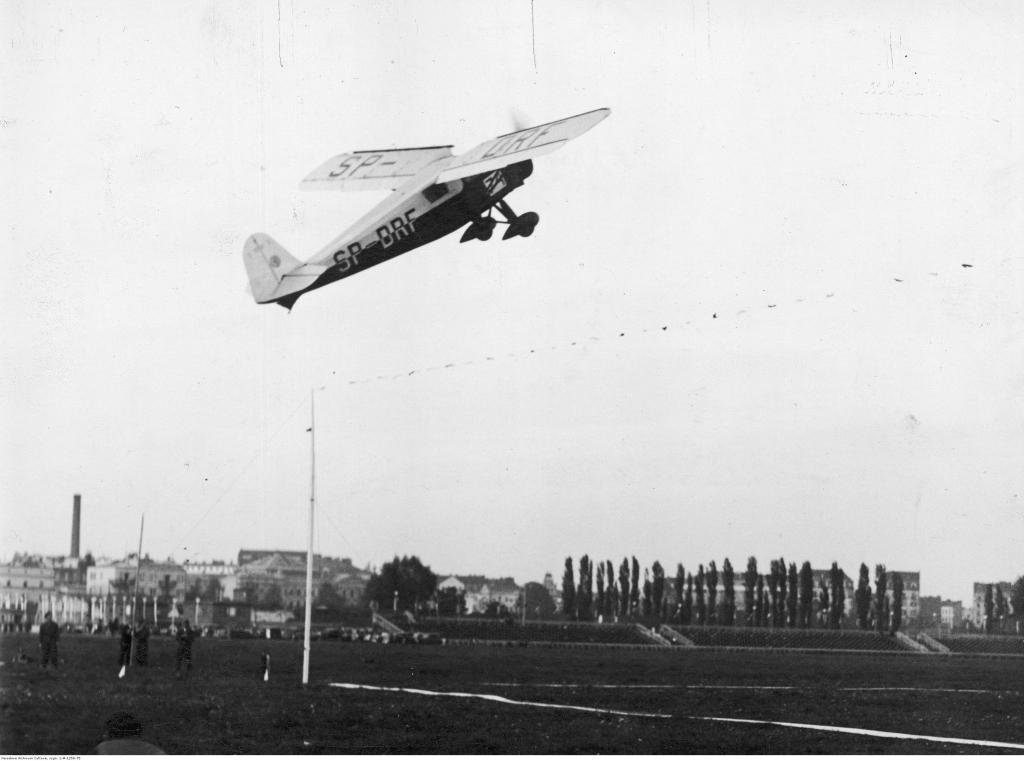

The RWD name comes from the initials of three talented young engineers – Rogalski, Wigura and ewiecki – who established their own company and designed increasingly successful aircraft. In the early 1930s the sports aircraft competition to win was the Challenge International des Avions de Tourisme, an incredibly demanding series of trials for aircraft intended to accelerate the development of aeroplane technology for trans-European touring.

The exacting regulations filled a fat book, and some of them made for a very difficult compromise, the wings had to fold for easy storage, and good short-take off and landing performance was desirable and the competition entailed a high-speed race around Europe, demanding a high cruise speed. In 1932, an upset victory rocked the pundits expectations – the Challenge was won by a Polish RWD-6 aircraft, flown by Żwirko and Wigura.

Losing on their home turf, the German contingent looked on bitterly as the Polish crew were decorated at the Berlin-Staaken airfield ceremony. Sadly, several weeks later the victorious crew perished in heavy weather over Czechoslovakia. Since Poland won the Challenge, it had to host the next contest in 1934, and this time the new Germany (under Hitler) intended to win back the Challenge. With state aid, Messerschmitt’s Robert Lusser set about designing an aircraft which would have a chance of winning against anything the Poles could bring (no other country actually counted as viable competitors any more). This was to be the Messerschmitt Bf-108 Taifun, which in its first iteration with its huge flaps and tiny ailerons close to the wingtips, was extremely unforgiving to fly.

The Poles were working on an improved version of the RWD-6, designated ‘RWD-9’. The work on the design of aircraft started 15 months before the Challenge, and seven months after work had started the first prototype flew. At the same time a new Polish radial engine was being designed by Stanislaw Nowkuński. The new aeroplane was revolutionary, as it managed the combine seemingly contradictory: a top speed to stall speed ratio over 5, requiring a very high cruising speed with a very low stall speed. This necessitated a hugely sophisticated wing, with leading edge slats, flaps, flaperons and spoilers, which was able to generate a very high coefficient of lift of 3.5. The light alloy engine developed almost 300 horsepower despite weighing a mere 148 kilos.

Despite the fact that Polish crews had only a month to practice on type ahead of the Challenge, they came first and second! They had not only demonstrated absolutely devastating STOL characteristics, but their RWD-9 aircraft withstood a murderous 9,500 km race around Europe with no problems. What most impressed educated observers was the astonishing fact that the top speed of the Polish monoplane (152 knots) was over 5 times higher than its stall speed (29 knots). Its take-off roll was a minuscule 54 metres (180 feet). Experienced pilots, such as Captain Jerzy Bajan (the Challenge winner) were able to make full use of those extraordinary flight characteristics, further aided by an effective landing gear design which made very short violent landings possible.

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

The RWD-6 was basically a prototype, and only eight were built. Some of them led extremely eventful lives: two were sold to Spain, where they were used as liaison aircraft in the civil war. One crashed into the Baltic Sea while carrying a famous general to see his wife returning from the US on a Polish ocean liner. One was bought by a French aviation institute and was irreparably damaged when ignorant mechanics used acid to clean the engine (many parts were made of the lightweight Elektron which dissolves in acid). Nowkuński, the engine design genius, died in a climbing accident in the Tatra mountains. Not a single RWD-9 survived the war.

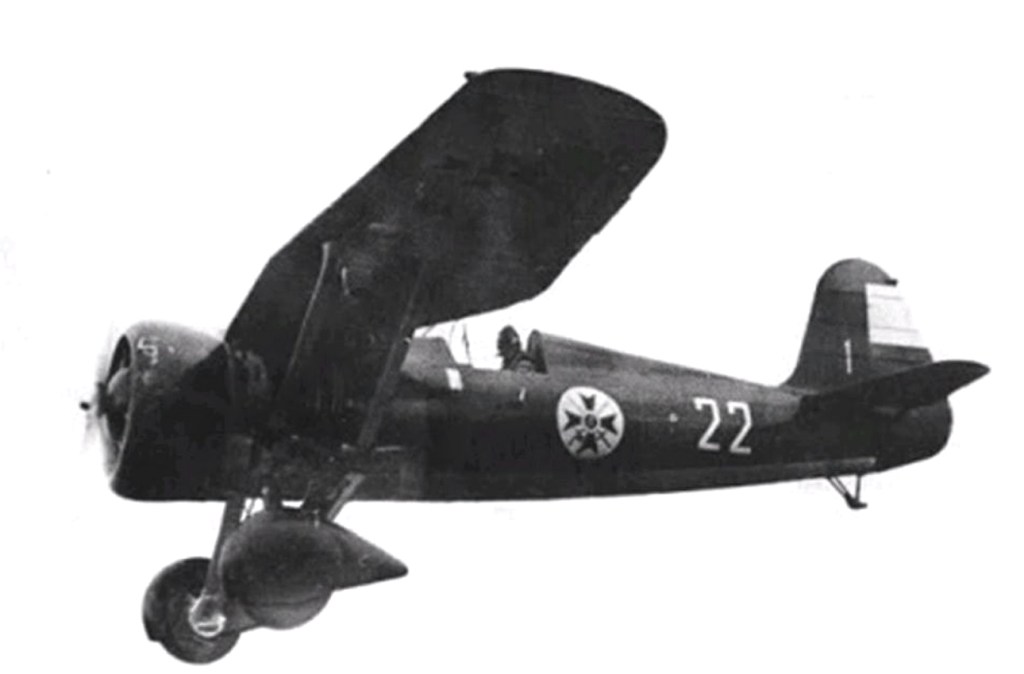

9. PZL P.24: Greek Hero

The gull-winged PZL P-11 fighter is famed for its valiant but ill-fated use by pilots in defending Poland in 1939, where it faced an horrofic mauling by the formidable Messerschmitt Bf 109, then the best fighter in the world. The P.24 was one of a longer line of gull-winged aircraft, that started with the P-1 designed by Zygmunt Puławski. This all-metal monoplane flew in 1929 and was a vision of the future, at a time when most European countries were firmly in the biplane era. The P-1’s distinctive ‘bent’ wing gave the pilot superior forward vision over the cowling of the Hispano inline engine. Unfortunately the government decided that Poland would manufacture a military aircraft engine under license, and that it would be a rather bulkier air-cooled radial designed by Roy Fedden at Bristol. Because of this questionable move to radial engines, the sleek inline P-1 never progressed beyond two prototypes. It was redesigned into the radial-engined P-6, and then the inline-engined P-8; the former was developed into the P-7 which first flew in 1930 and entered full service in 1933.

The designer Puławski was killed while test-flying an amphibian aircraft of his own design, and the design team was taken over by Wsiewołod Jakimiuk (who later gave the world the DHC Chipmunk). The P-7 was developed into the P-11, which already obsolete, had to defend Polish skies against the Nazi onslaught. But there is another plane stemming from the same DNA which was never used by the Polish air force.

Poland wished to export aircraft, but the license agreement with Bristol precluded the sale of Warsaw-built engines abroad. A solution came from France, from Gnome-Rhône: they would supply sample engines if Polish industry chose to buy engines for export-spec planes from them in the future. Long story short, the P.24 was born, each armed with two Swiss 20-mm Oerlikon cannon. The aeroplane was offered to a number of countries, and during a firing run at a Turkish range one of the underwing-mounted Oerlikons jammed and blew up; the wing spars remained undamaged and Bolesław Orliński was able to land the plane safely.

The PZL P.24 became one of the most successful Polish aviation export products. It was sold to Bulgaria and Greece (each version reflecting the needs of the customer) and was sold alongside a production license to Romania and Turkey. Bulgarian fighters during the war were assigned to a fighter combat school (a factory designed by Polish engineers was planned to produce a new model under license but the war intervened). Romanian P-24 aircraft fought against the Soviet Union. Turkish ones were never used in combat and were retired in 1945.

However, Greek PZL P.24 fighters saw a lot of action. When Fascist Italy attacked Greece on 28 October 1940, a force of 24 serviceable planes (out of 36) rose to repel Italian bombers and fighters. What is fascinating is the fact that until the impatient Germans entered the fray, the Greek fighters were efficiently repelling the Italians! In all, the Greek P.24s shot down 37 Italian and 3 German aircraft, with a loss of 35 own aircraft. The ramming of an Italian Z.1007 bomber by Lt. Mitralexis became an event immortalised in Greek history books.

In total, 97 P.24 production aircraft were built in Poland and 52 abroad under license. The only survi-vor can be found in a museum in Turkey.

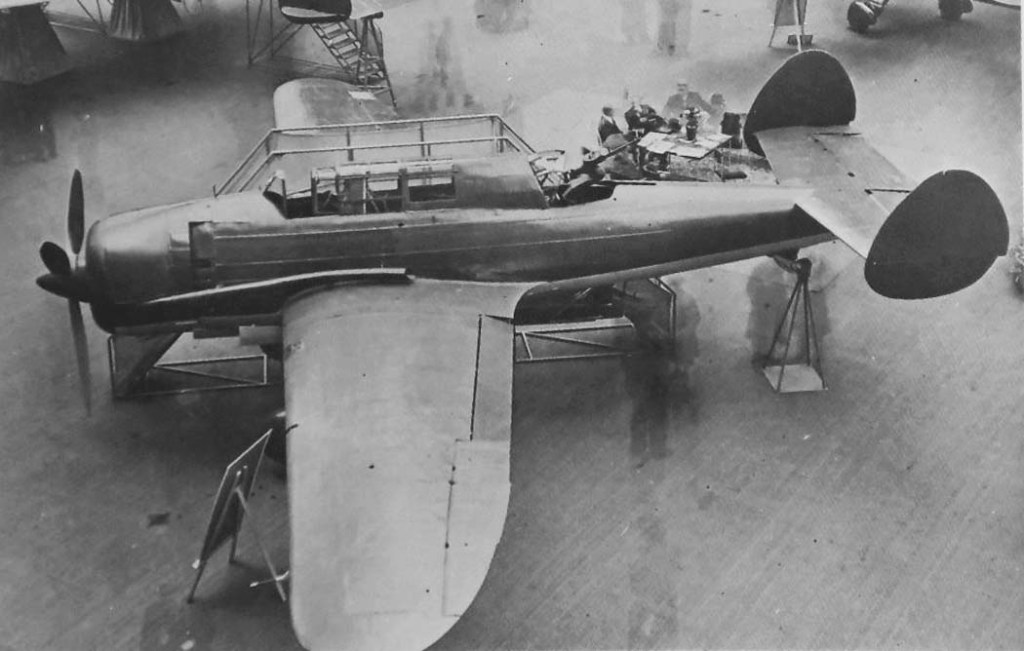

8. PZL-37 ŁOŚ (Moose): Laminar flow

In 1934 a PZL works engineer, Jerzy Dąbrowski, started work on a fast monoplane bomber which he confidently expected to exceed the air force specification which demanded two engines, a 1200 km range, an offensive load of twenty 100 kg bombs, the ability to carry 300 kg bombs, and top speed over 217mph (350 kph). His metal, low-wing aircraft had a very thin wing which had to be made thicker to accommodate bombs. When tested in the Warsaw Aerodynamics Institute wind tunnel, his airfoil seemed to produce less drag than comparable designs, actually less than the textbooks of the day said it should have: it was in fact, the first laminar flow airfoil developed in Poland, and one of the first in the world.

The PZL-37 Łoś bomber featured some other innovations, including a revolutionary main landing gear unit, with a single strut supporting twin, elastically suspended wheels – this arrangement was very compact, easy to fold into the engine nacelle, and well suited to operating from unprepared fields. After a number of teething problems and modifications (including the introduction of twin vertical tailfins) the ‘Moose’ went into production. Over 90 examples were completed and test-flown before the war.

The aeroplane, powered by license-built Bristol Pegasus engines, was smaller than comparable Western bombers, but carried a similar bomb load. It was also seriously fast (223 knots or 256mph). Over 50 units were ordered by foreign customers, but none were built before the war (they would be even faster with more powerful Gnome-Rhône powerplants). Two airframes received Bristol Perseus sleeve valve engines for experimental purposes.

In September 1939 the units equipped with the Łoś fought bravely against German armour and supply columns, but unfortunately their full potential was never reached due to grave tactical errors by the Polish high command. Some airframes were evacuated to Romania where they remained for the rest of the war; some of them were successfully used by the Romanians against the Soviet Union.

Several survived the War, which the Romanian government offered to return to Poland, however the Moscow-serving Communist government declined the offer as the existence of such planes would contradict the official propaganda line which claimed that all pre-war Polish aircraft were utterly inferior. At least two aircraft were repaired by the Germans and sent to the Rechlin E-Stelle for testing. Two examples of the aircraft were flown by the Soviet air force.

7. PZL-46 Sum (Catfish): Daring raid

Work on the PZL-46 light bomber commenced in 1936, with Stanisław Prauss as the lead designer. Tadeusz Sołtyk, who would later work on the notorious TS-8 Bies and TS-11 Iskra, was his deputy. Henryk Milicer, who would go on to design the British Percival Provost trainer, was also a member of the team.

The new plane was to replace the PZL-23 Karaś (crucian carp) light reconnaissance bomber in Polish Air Force service. It was first flown in early 1939, soon after being presented at the Paris Air Show. It had a unique ventral gunner gondola, which in its last iteration lowered itself under the gunner’s body weight in flight, with a rubber rope system damping the downward motion. The air force ordered 300 PZL-46 aircraft, powered by license-built Bristol Pegasus engines, and an export version for Bulgaria was also planned.

Only the second prototype was in flying condition when the invasion happened and it was evacuated to Romania. Though Romania and Poland were officially allies, under German pressure Romanian officials were interning the servicemen of Poland and requisitioning their equipment. A deception was concocted to avoid the PZL-46 falling into German hands. Feigning submissiveness, it was agreed with local authorities that it would be flown to another airfield to make it available for inspection by Romanian engineers. With the local authorities deceived, instead it escaped back to Poland on September 26th, carrying an officer courier with orders for the commander of the defence of Warsaw. It was flown by the exceptionally gifted engineer and test pilot, Stanisław Riess. He tried to land at the Okęcie airfield in Warsaw, but this was already occupied and he was greeted with fierce anti-aircraft fire. He managed to avoid getting shot down and landed at the edge of the nearby Pole Mokotowskie airfield. The following morning Riess managed to take off in the dark, deftly avoiding German fighters, and flew to Kaunas in Lithuania, where the aircraft was interned. When the Soviet Union annexed Lithuania it probably stole the sole PZL-46; its subsequent fate is unknown.

Stanisław Prauss reached England and in 1940 was employed by Westland Aircraft, where he worked on the Lysander, the Whirlwind and the Welkin. In 1946 he found employment at de Havilland, where he continued to work when the company became Hawker Siddeley; notable aircraft he contributed to included the Comet, Trident and the A300. Stanisław Riess also reached England, and was employed by the AAEE at Boscombe Down. He was assigned the task of finding the reasons for the tendency of the Handley Page Halifax to enter a flat spin: during one of the flights he was unable to recover from the spin and was killed in the crash. The data collected during the fatal flight helped cure the problem.

6. RWD-11: Faster than fighters

In 1934, the RWD design team started work on a light twin for the ministry of transport, a design intended to carry eight people over medium distances at high speed. The ministry did not pay at first, as a form of revenge on the factory which had refused to let itself be nationalised.

During flight testing, flutter was encountered for the first time on a Polish-designed aircraft. To discover the range of wing vibrations the Polish engineers used a gramophone installed at a right angle, with the record replaced with a cardboard sheet…and a pencil. The necessary changes revealed in this ingenious testing were introduced and the RWD-11 proved to be safe and pleasant to fly. With its two 200 hp Walter Major engines and refined aerodynamics it boasted an impressive performance.

The prototype was used in a feature film where it took part in scenes filmed with a flight of PZL P-11 fighters. During the filming, the RWD factory test pilot, Aleksander Onoszko, outran the escorting fighters, thus creating even more animosity against RWD within the red-faced air force establishment. Their pride stung, rather than ordering the RWD-11 as a fast medevac aircraft or a multi-engine trainer, the top brass simply pretended it did not exist.

The sole prototype suffered a hydraulically operated landing gear malfunction in August 1939, making an evacuation from Warsaw impossible. It is believed to have been repaired and to have served as a liaison aircraft with the Luftwaffe. As for the pilot, Aleksander Onoszko, he flew 43 combat sorties in World War II with the Polish 304 Bomber Squadron on Wellingtons, later flying transatlantic missions on BOAC B-24 Liberators.

5. Iskra – The Legend

The Iskra (‘spark’) was the first indigenous Polish jet aircraft design. The TS-11 Iskra was a straight-wing trainer designed by Tadeusz Sołtyk (mentioned above in the PZL-46 description) at the Warsaw Institute of Aviation. It made its first flight on February 5 1960. Between 1962 and 1987 more than 420 examples were manufactured, fifty of which were exported to India. The Indian Air Force operated Iskra trainers from 1976, received a further 26 examples in the 1990s, before retiring the type in 2004.

The Iskra is the mount of the Polish national aerobatic team, the Biało-Czerwone Iskry (the white-red sparks). The group has its roots in the Grupa Rombik (The Little Rhombus Team) that performed at air shows in Poland in the early 1970s. The Iskry made their debut in 1991, at the Ławica airport show in Poland. The Polish industry then showcased the Iskra jet all around Europe, the jet making appearances at the 1976 and 1977 Farnborough Air Shows, and at the 1977 Paris Air Salon. In 1964 the TS-11 prototype broke four in-class records, including a speed record of 521mph (839kph.) Intriguingly, the TS-11 never received a NATO reporting name.

Save the Hush-Kit blog. Our site is absolutely free. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here. Your donations keep this going. Thank you.

In the 1960s Iskra stood a chance to become the standard jet trainer of the Warsaw Pact air arms, a hugely significant opportunity considering the potential order size. It lost, however, to the Czechoslovakian Aero L-29 Delfín, despite beating it in the official assessment. It was clear the Soviets had no wish for the Poles to win anything. Poland became the only Warsaw Pact nation to operate the Iskra.

A total of 110 examples of the Iskra were still in service in the Polish Air Force in 2002, by 2013, only thirty airframes were still flying. In 2016 Poland took delivery of the Alenia Aermacchi/Leonardo M-346 – the replacement of Iskra. The last training sortie made by an Iskra took place on 9 December 2020. Currently the Polish Air Force only has its aerobatic team, the Biało-Czerwone Iskry, flying the type.

4. TS-16: Killed by the ‘Mighty Integral’

After the TS-11, designer Tadeusz Sołtyk then proceeded to pursue an even more ambitious goal – the creation of a modern supersonic aircraft, the TS-16 Grot (‘Arrowhead’). The first steps in the Grot project were taken in 1958. The main intention was to create a lead-in trainer that would allow the pilots to get acquainted with flying a supersonic aircraft. With the rather demanding MiG-21 forming the bulk of the Polish Air Force – this was very much needed. Initially, the design concept was known as the TS-13, which started in 1959. It resembled the F-101 Voodoo in wing planform. Then, after the T-38 Talon made its maiden flight, the Grot was redesigned with the benefit of consideration of the Northrop design, and ultimately was proposed to the air force. However, politics stopped the Grot dead in its tracks.

The command of the air force suspected that the name of the jet referred to the wartime pseudonym of General Stefan ‘Grot’ Rowecki. He was the chief commanding officer of AK (Armia Krajowa – Home Army) which was a resistance movement in Poland during the War, subordinate to the legal Polish government in exile. It had a much smaller Communist counterpart, AL (Armia Ludowa – People’s Army). The AK officially disbanded on January 19 1945 to avoid armed conflict with the Soviets and civil war. Rowecki had been murdered by the Nazis at the personal order of Heinrich Himmler, but was considered an enemy of the Soviets and thus taboo. The second problem stemmed from the ‘unlucky’ project designation – the inauspicious ‘TS-13’ was re-designated ‘TS-16’.

It had a delta wing with a 45-degree sweep, similar to that of the MiG-21. Two variants of the jet were to be manufactured – B and A, the former was to be a trainer, the latter was to an attack aircraft. For commonality, armament was to be the same as that of the ‘Fishbed’. Ultimately, the Grot design was modified to have one of the MiG-19’s RD-9B engines in place of the originally decided twin SO-2s.

From 1961 to 1963, the design was finalised. The TS-16RD was ready by the mid-1960s. Nevertheless, The Mighty Integral (as Tom Wolfe referred to the Soviet authority) decided to cancel the project and limit the capabilities of the Polish design bureaus. The Soviets had a different plan for Poland – it was to license-manufacture Soviet design airframes, instead of developing designs of its own. Even though the project was not cancelled immediately, it suffered from a lack of manpower. Only 40 engineers worked on it, while 200 would have been needed to finish it. Nonetheless, ultimately, the Grot was submitted for governmental approval. The Scientific Council of Defence Ministry to consult with the Soviet authorities. This was the death knell of an extremely promising design.

3. PZL-104 Wilga

Competition gliding’s popularity in Poland was growing. A reliable workhorse towplane was in demand, moreover, there was a lack of a modern, light multi-purpose aircraft. Short take-off and landing would be a desirable, combined with good performance and low-operating costs. The requirement led to creation of the PZL-104 Wilga (thrush) at the WSK Okęcie facility. Designed by a team led by Ryszard Orłowski, it was made entirely of metal. The aircraft received a flat WN-6RB engine designed by Witold Narkiewicz. The prototype made its maiden flight on April 24 1962. The engine tended to overheat requiring fuselage redesign.

The engineer Bronisław Żurakowski created the the Wilga 2 prototype with a new lighter fuselage in 1963. Still using a flat Continental engine, the aircraft was still troublesome. The ultimate solution came in the form of the adoption of the far more powerful AI-14 Soviet radial engine (which worked well at low RPM). This also contributed to the excellent STOL properties of the aircraft. With all these modifications in place the aircraft became the Wilga 3. This was further refined as the PZL-104 Wilga 35 which made its maiden flight in June 1967.

The Wilga proved a workhorse, excelling at whatever was asked of it, be it towing gliders, leisure flying or as a sporting aircraft*. Indeed it was a particularly good as a sporting aircraft, the Poles dominating the FAI precision flying championship in Wilgas for many years. It was in fact so good, that the championship rules were changed to end the unmatched reign of this PZL design, perhaps the most compelling proof of the the type’s excellence.

* An armed counter-insurgency prototype was built too

2/1. Agro-Aviation – The Polish Specialty: PZL M-15 and Dromader

In demonology, Belphegor is one of the seven princes of Hell notorious for seducing people by suggesting to them ingenious inventions to make them filthy rich. Its aircraft namesake is often described as the ugliest aeroplane ever built, its tough unlikely appearance somewhat like allotment buildings frozen halfway in transformation to flying locomotive; its smoke-belching ultra low-flying across bleak remote farmlands could be seen as a very visceral metaphor for the communist era. Its origins are cloaked in intrigue – according to one engineer who worked at Mielec at the time part of the original specification was for an chemical warfare aircraft to brutally put down insurgencies or revolutions in communist states on the verge of Islamic reformation with genocidal attacks. NATO suspected it had a chemical warfare capability with the West in mind, perhaps even as a platform for the spraying of deforestation to rob NATO forces of cover. It is likely that NATO’s scaremongering was actively incited by the Soviet Union and not rooted in fact. The unofficial name ‘ Belphegor’ was given somewhat ironically to a sales rep by Andrzeja Abłamowicz, in reference to the Phantom of the Louvre, when he was asked if the type had a name (at Le Bourget in 1976). Though popularly used abroad, in Poland the type is generally known by its designation. Along with the Coandă 1910 and the Screamin’ Sasquatch 1929 Taiperwing replica, it was one of only three biplane jets in existence.

Among the Soviet bloc, Poland’s aerospace industry had a particular love for the agricultural, a long-lasting affair that dated back to the interwar years. The CWL facility created the first aircraft-mountable spraying systems that were then fitted onto the Potez XV, Breguet XIV and Fairman Goliath F-68 before the hiatus of invasion and occupation.

During the Cold War period, Poland was asked by the Soviets to develop an agricultural airframe that would incorporate jet propulsion.What followed was an utterly bizarre beast, the PZL M-15 Belphegor*. Not only was it the only agriculture-focused jet design, it was also the only serially-produced jet-powered biplane. The goal was to replace the ubiquitous An-2 (produced in series in Poland for the Soviets). The Belphegor was a successful design for its time – when economy and fuel consumption were not a priority! It was tailored to serve large fields and was capable of long-haul ferry flights. With vast fields to operate over, as impractical as the aircraft seems today, it served its purpose well back when it was needed. Almost 200 examples were made between 1976 and 1982.

While the M-15 was a successful design, the An-2 remained an extremely good agricultural platform. When the Mielec facility that manufactured both decided to open itself towards the West, they met with an opportunity to provide the ASh-62 engines from the An-2 to the US company Rockwell, to power the Thrush Commander. The Polish designers noticed the Commander platform had further growth potential, and created a prototype of their own making using only some elements of the American predecessor. Known as the M-18 Dromader, the M-18 was an export hit. An impressive 760 examples have been sold all around the world. In a case of ‘ploughshares to swords‘ at least one airframe was used as a combat aircraft in the civil war in Yugoslavia.

A smaller specialised crop sprayer aircraft was built in smaller series at the Okęcie works, the PZL-106 Kruk (Raven), also tested with a turboprop. For 42 years, Polish pilots flying the Kruks have been supporting crop-dusting operations in Sudan (worthy of an article in itself that we may come back to).

Thank you. Our aviation shop is here and our Twitter account here @Hush_Kit. Sign up for our newsletter here. The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes will feature the finest cuts from this site along with exclusive new articles, explosive photography and gorgeous bespoke illustrations. Pre-order The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes here.

Words: Piotr R. Frankowski, Jacek Siminski from The Aviationist, Joe Coles

Images: NAC (Polish National Digital Archive), Wikimedia Commons

QUESTION: presumably the test phase of the Belphegor project must have featured a more sensible and aesthetically pleasing aircraft..? what could possibly have birthed this? ANSWER: the Lala-1

- Echoes in the Sky@exoticaviation

This was superb. Thank you!

Todd Wolfe? I think you mean Tom. And the Mighty Integral was a spaceship in the novel “We” by Yevgeny Zamyatin. Wolfe used it as a symbol of Soviet close-mouthedness abou t the identity of their rocket program’s Chief Designer.

Tom indeed! Thanks. And yes, the hyperlink goes to the We reference.